Re: Global Monetary Breakdown: Part I

We promised readers inflation by Q4 2011 and everywhere we looked, we found it.

But before publishing we wanted to be sure that our reading of the data was sound, rather than a "told you so" piece that selected for inflationary trends while ignoring deflationary ones.

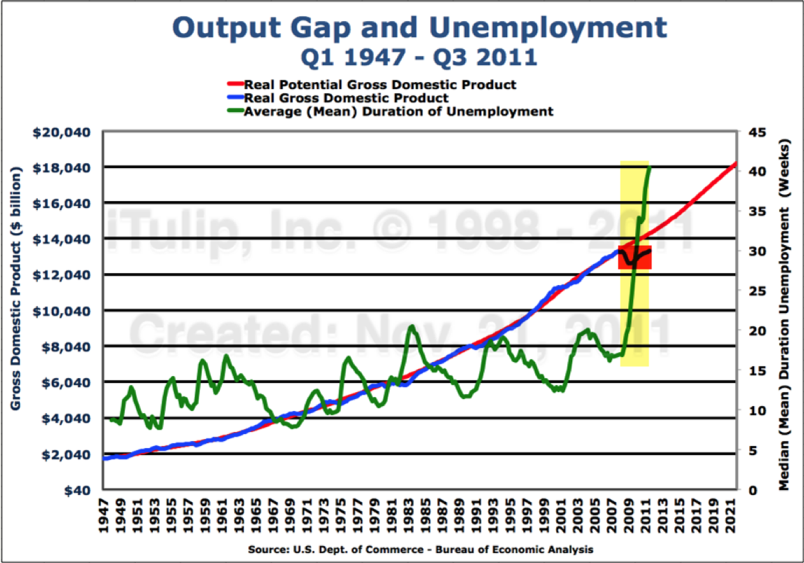

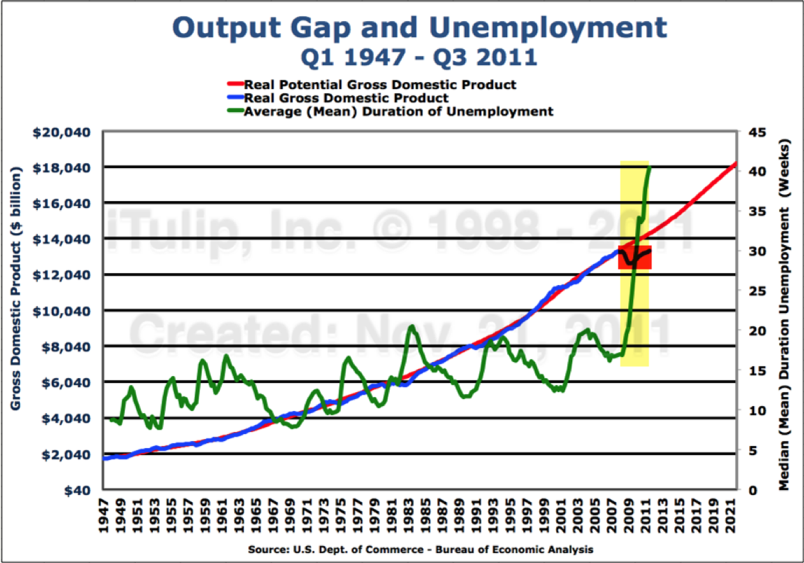

In fact, we discovered inflation in the most unlikely places, at least to those who see a giant output gap and high unemployment and ask, Where is the inflation going to come from when wages are not inflating? It's an argument we've had even among our members for years before the crisis.

Can we have high unemployment and high inflation, too? We hope to site evidence of our current circumstances to put this question to rest once and for all.

We start with the current predicament, a post bubble recession output gap.

We're used to seeing inflation in insurance, health care, education and other non-traded services that have been inflated via the sector-specific credit-money of the rent seeking institutions of the FIRE Economy.

From 1999 to 2008, here at iTulip we counted housing among the consumer costs that grew due to sector-specific credit-money inflation. Housing prices inflated to consume more than 40% of personal consumption expenditure by 2008. We can now count housing out due to the collapse of the housing bubble that left behind the usual scar: asset price deflation.

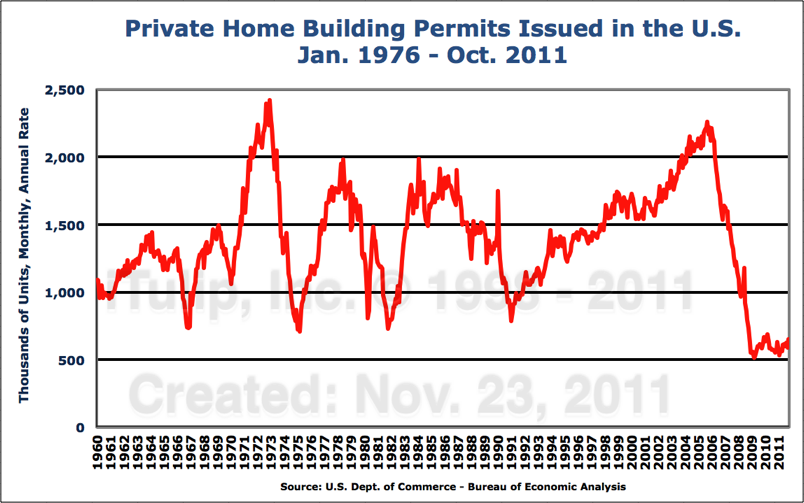

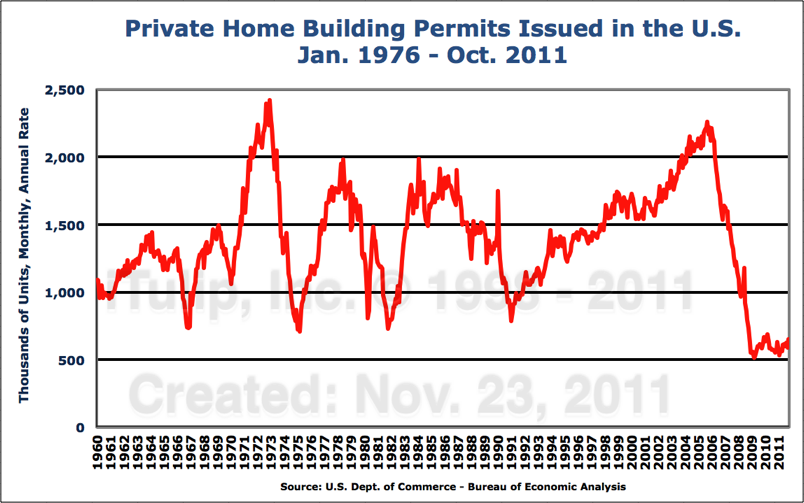

Demand for new homes has never been lower since records began in 1960. But the devil's in the details. Which housing markets have suffered the most? High, mid, or low end?

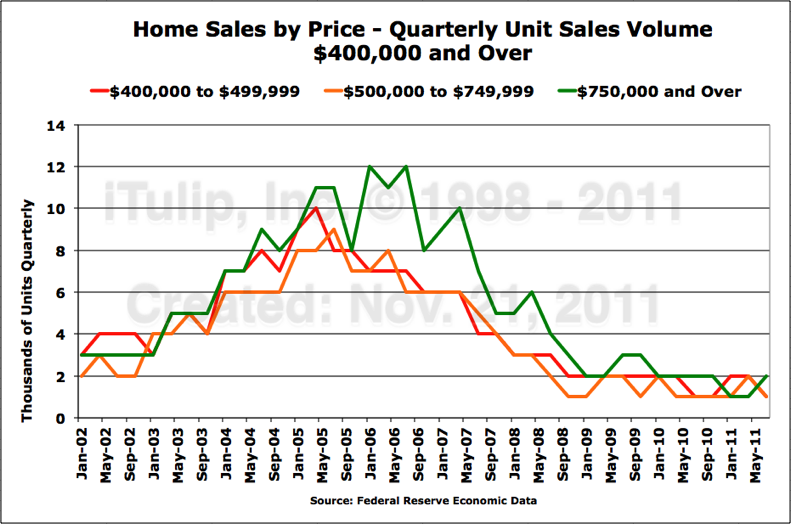

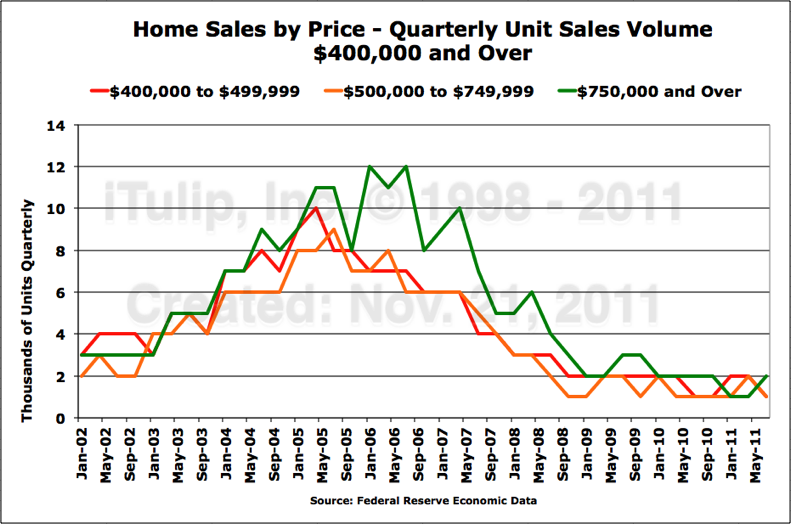

If you're trying to sell a home over $750,000, forget it. The market is virtually dead. At the peak of the bubble in 2006, 12,000 such homes old in a three month period. Under normal circumstances approximately three times that many sell in a quarter. Across the entire United States, fewer than 1,000 homes in that price range sold in Q2 2011.

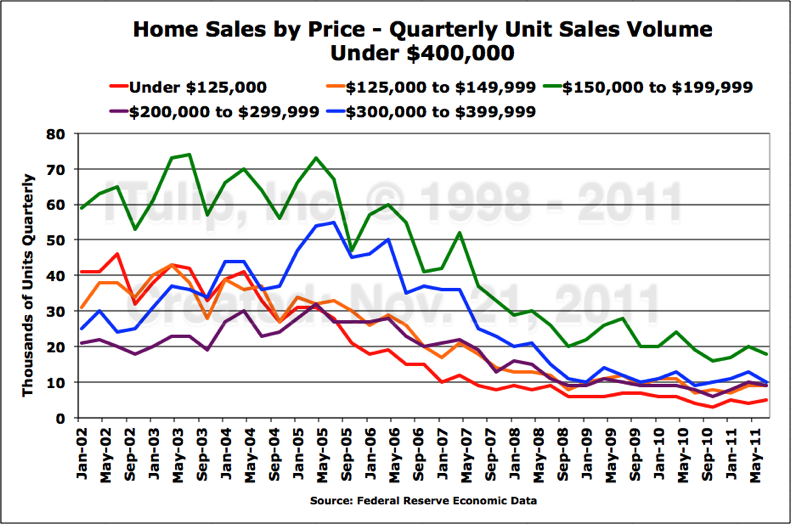

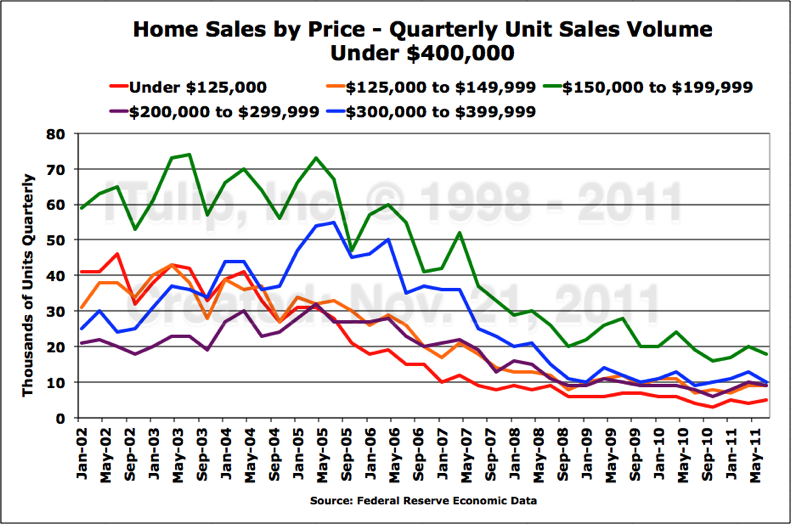

While the high end of the housing market has seen the greatest decline, unit sales at the mid and low end housing market are off 50% to 85% from the peak.

Sales in the previously hot $150,000 to $200,000 market has fallen from over 70,000 units in Q2 2005 to under 20,000 in Q3 2011. This despite focused attention by banks and government to reflate the bread and butter of the U.S. housing market.

Interestingly, the very low end of the market is almost as bad off as the very high end. It peaked at 40,000 units per quarter in the spring of 2004, only to collapse to 5,000 in Q3 2011.

But deflation in housing is the obvious and predictable consequence of a dearth of housing credit-money needed to re-inflate housing prices; its engine -- the asset-backed securities market -- is still on a central bank respirator. But there's plenty of other credit-money loss and available to create inflation elsewhere, as well as cost-push inflation from persistently high energy prices.

You'd expect price inflation in food. Food producer prices are susceptible to rising energy input costs. Food producers can pass these on to consumers due to guaranteed demand: people got to eat. Even the mainstream media has noticed that a Thanksgiving dinner will be 30% more expensive this year than last.

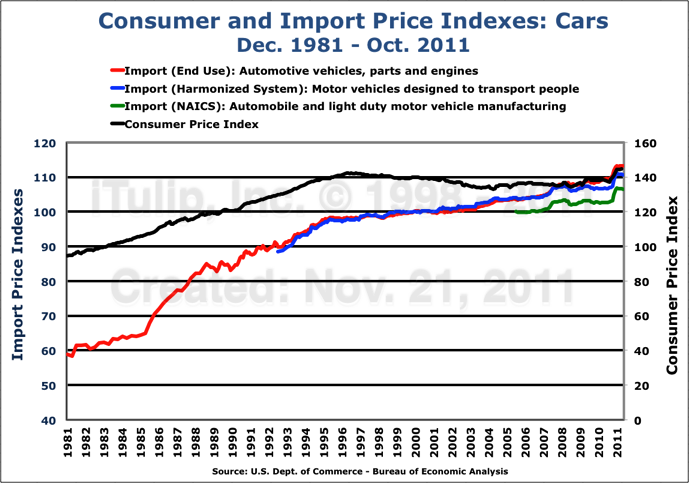

But cars? The big surprise in our research for this article is the surge in car prices.

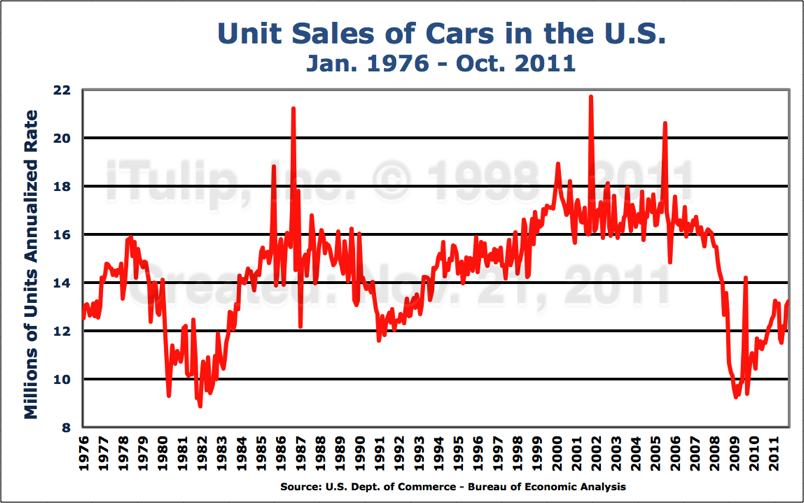

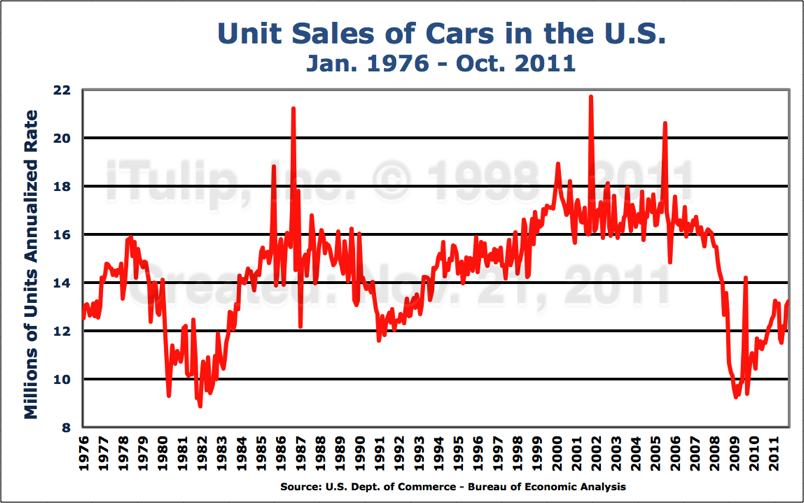

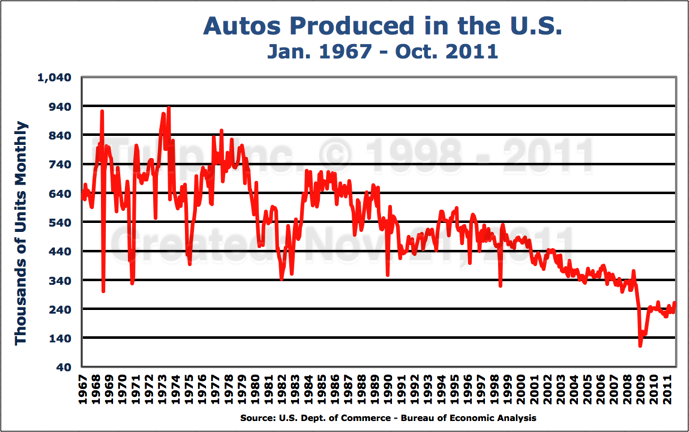

As you'd expect, with unemployment high and wages stagnant, the auto sales business is awful. Unit sales are still below the level first reached in 1983 when the U.S. economy was 1/3 as large as today's.

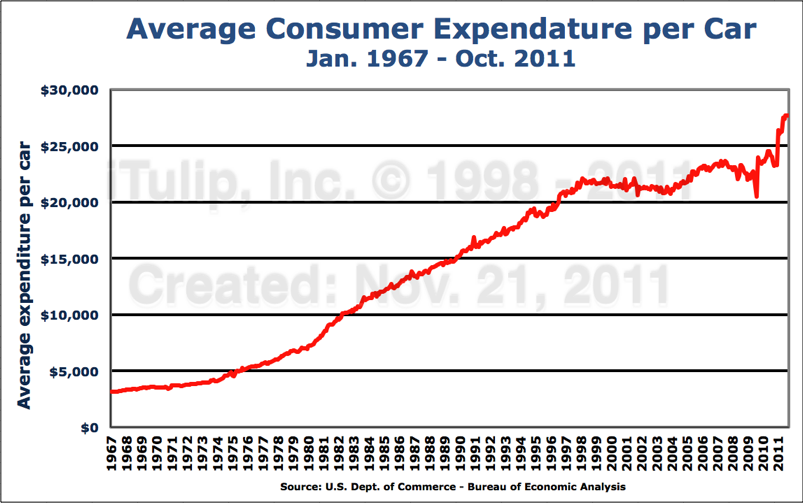

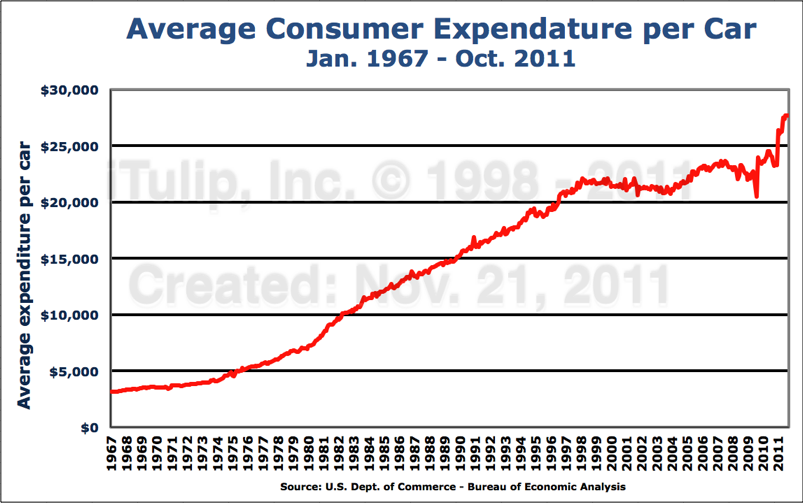

Yet the average expenditure per unit is up more than at any time on record.

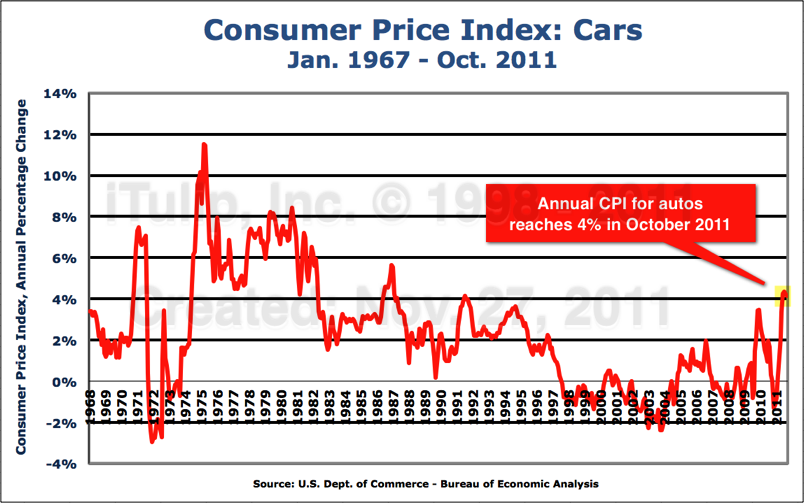

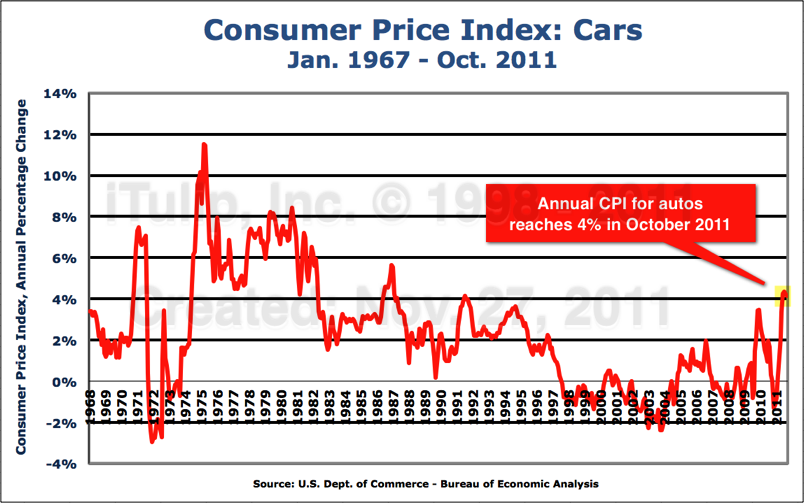

Even the consumer price index of car prices shows the trend: prices have risen more over the past several months than during the worst of the 1970s inflation.

The trick to seeing inflation trends on our output gap era, we've learned, is to focus on goods that are measured as units rather than as in aggregate. A car or a house is a discrete unit the price of which cannot be so easily reformulated into a more politically palatable index value.

What can and will the Fed do about it?

How will the Bullhorn deal with it? FIRE Economy interests that own the US media want the Fed to keep up the effort to reflate housing prices by buying long duration treasury bonds. Calling attention to food prices and other inflation is at cross purposes.

Look for the full State of the Union portion of the series by Wednesday.

Originally posted by WDCRob

View Post

But before publishing we wanted to be sure that our reading of the data was sound, rather than a "told you so" piece that selected for inflationary trends while ignoring deflationary ones.

In fact, we discovered inflation in the most unlikely places, at least to those who see a giant output gap and high unemployment and ask, Where is the inflation going to come from when wages are not inflating? It's an argument we've had even among our members for years before the crisis.

Can we have high unemployment and high inflation, too? We hope to site evidence of our current circumstances to put this question to rest once and for all.

We start with the current predicament, a post bubble recession output gap.

We're used to seeing inflation in insurance, health care, education and other non-traded services that have been inflated via the sector-specific credit-money of the rent seeking institutions of the FIRE Economy.

From 1999 to 2008, here at iTulip we counted housing among the consumer costs that grew due to sector-specific credit-money inflation. Housing prices inflated to consume more than 40% of personal consumption expenditure by 2008. We can now count housing out due to the collapse of the housing bubble that left behind the usual scar: asset price deflation.

Demand for new homes has never been lower since records began in 1960. But the devil's in the details. Which housing markets have suffered the most? High, mid, or low end?

If you're trying to sell a home over $750,000, forget it. The market is virtually dead. At the peak of the bubble in 2006, 12,000 such homes old in a three month period. Under normal circumstances approximately three times that many sell in a quarter. Across the entire United States, fewer than 1,000 homes in that price range sold in Q2 2011.

While the high end of the housing market has seen the greatest decline, unit sales at the mid and low end housing market are off 50% to 85% from the peak.

Sales in the previously hot $150,000 to $200,000 market has fallen from over 70,000 units in Q2 2005 to under 20,000 in Q3 2011. This despite focused attention by banks and government to reflate the bread and butter of the U.S. housing market.

Interestingly, the very low end of the market is almost as bad off as the very high end. It peaked at 40,000 units per quarter in the spring of 2004, only to collapse to 5,000 in Q3 2011.

But deflation in housing is the obvious and predictable consequence of a dearth of housing credit-money needed to re-inflate housing prices; its engine -- the asset-backed securities market -- is still on a central bank respirator. But there's plenty of other credit-money loss and available to create inflation elsewhere, as well as cost-push inflation from persistently high energy prices.

You'd expect price inflation in food. Food producer prices are susceptible to rising energy input costs. Food producers can pass these on to consumers due to guaranteed demand: people got to eat. Even the mainstream media has noticed that a Thanksgiving dinner will be 30% more expensive this year than last.

But cars? The big surprise in our research for this article is the surge in car prices.

As you'd expect, with unemployment high and wages stagnant, the auto sales business is awful. Unit sales are still below the level first reached in 1983 when the U.S. economy was 1/3 as large as today's.

Yet the average expenditure per unit is up more than at any time on record.

Even the consumer price index of car prices shows the trend: prices have risen more over the past several months than during the worst of the 1970s inflation.

The trick to seeing inflation trends on our output gap era, we've learned, is to focus on goods that are measured as units rather than as in aggregate. A car or a house is a discrete unit the price of which cannot be so easily reformulated into a more politically palatable index value.

What can and will the Fed do about it?

How will the Bullhorn deal with it? FIRE Economy interests that own the US media want the Fed to keep up the effort to reflate housing prices by buying long duration treasury bonds. Calling attention to food prices and other inflation is at cross purposes.

Look for the full State of the Union portion of the series by Wednesday.

. on the plus side, the car has barely depreciated given the conditions we are discussing

. on the plus side, the car has barely depreciated given the conditions we are discussing

Comment