I've got a good friend whose a fund of fund hedge fund manager and after speaking with top hedge fund managers he said they don't believe gs or ms can survive without the balance sheet of a larger institution.

Announcement

Collapse

No announcement yet.

goldman sachs, morgan stanley next

Collapse

X

-

Re: goldman sachs, morgan stanley next

on cue...from the FT.

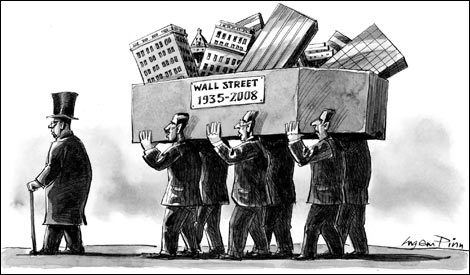

After 73 years: the last gasp of the broker-dealer

By John Gapper

Published: September 15 2008 19:15 | Last updated: September 15 2008 19:15

It sometimes feels as though my two decades as a financial journalist have been spent, first in London and then in New York, watching investment banks either collapse or be acquired: Barings, SG Warburg, JPMorgan, Bear Stearns, and now Lehman Brothers and Merrill Lynch.

This Sunday was different, however, because it marked not simply the end of Lehman and surrender of Merrill, but the last gasp of the independent investment bank itself. Morgan Stanley opened on Wall Street on Monday September 16 1935 and, 73 years later, almost to the day, the institution of the broker-dealer died.

Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley are the last hold-outs among Wall Street’s independent investment banks (although even Morgan Stanley sold out once before, to Dean Witter, in 1997). How long these two will spurn the capital backing of a commercial bank remains to be seen.

There will, of course, be investment banks in future. But they will be smaller, specialist institutions, like the merchant banks of old. There are plenty of advisory firms, hedge funds and private equity funds and this Wall Street crash will create more. All of those unemployed financiers will need something to do.

The full-service investment bank, buying and selling shares and bonds for customers as well as advising companies and trading with its own capital, is doomed. In order to generate the revenues needed to match larger institutions, banks such as Lehman scurried into risk-taking that eventually sunk them.

Stockbrokers such as Morgan Stanley were pushed out on their own by the 1933 Glass-Steagall Act, which enforced the separation of banks and investment banks. Their fate was probably sealed on May 1 1975, when fixed commissions for trading securities were abolished, setting off a squeeze on broking revenues.

“To stockbrokers, May Day means nothing less than the abolition of the system that has enriched them in good times and pulled many of them through during long periods of market slack,” Time magazine noted that year. Investment banks had relied on these commissions during the financial doldrums following the 1973 oil crisis.

Investment banks went on to enjoy 30 years of prosperity. They grew rapidly, taking on thousands of employees and expanding around the world. The big Wall Street firms swept through the City of London in the 1990s, picking up smaller merchant banks, such as Warburg and Schroders, on their way.

Under the surface, however, they were ratcheting up their risk-taking. It was increasingly hard to sustain themselves by selling securities – the traditional core of their business – because commissions had shrunk to fractions of a percentage point per trade. So they were forced to look elsewhere for their profits.

They started to gamble more with their own (and later others’) capital. Salomon Brothers pioneered the idea of having a proprietary trading desk that bet its own money on movements in markets at the same time as the bank bought and sold securities on behalf of its customers.

Banks insisted that their safeguards to stop inside information from their customers leaking to their proprietary traders were strong. But there was no doubt that being “in the flow” gave investment banks’ trading desks an edge. Goldman Sachs’ trading profits came to be envied by rivals.

Investment banks also expanded into the underwriting and selling of complex financial securities, such as collateralised debt obligations. They were aided by the Federal Reserve’s decision to cut US interest rates sharply after September 11 2001. That set off a boom in housing and in mortgage-related securities.

The catch was that investment banks were taking what turned out to be life-threatening gambles. They did not have sufficient capital to cope with a severe setback in the housing market or markets generally. When it occurred, three (so far) of the five biggest banks ended up short of capital and confidence.

This leaves Goldman and Morgan Stanley on the spot. A bank can be highly skilled in risk management and trading, as Goldman has proved. Yet a single big mistake, as we have now witnessed, may spark a fatal spiral. Even a Fed guarantee of short-term funding could not save Lehman from chapter 11 bankruptcy protection.

It seems to me that Goldman and Morgan Stanley have two options. One is to follow Merrill and sell out to a large commercial bank with a big capital and deposit base. That could provide them with sufficient backing for their capital markets divisions, which can be revenue and profit powerhouses in good times.

The second is to scale back heavily, or abandon, their broker-dealer arms and become more like big hedge funds or private equity funds. In Wall Street jargon, this would involve a switch from sell side to buy side, where most money is now made. In exchange for becoming much smaller, they might retain their high margins.

My guess is that Morgan Stanley will opt for the first and Goldman for the second. It is sad to witness 73 years of investment banking history end this way but there is no use in denying it. Goodbye to all that.

Comment

-

Re: goldman sachs, morgan stanley next

actually I just signed up to his site, due to the current turmoil they are giving premium subsciption for free with access to heaps of analysis of current events and his team of economists. looks very good so far!

Comment

Comment