Re: Credit inflation, Deflation: Prechter Interview

The only true facsimile of an "anti-dollar" asset class would be all those asset classes that are not dollars. And not that good a one at that. The whole exercise of dividing the world into dollar and anti-dollar is a flawed enterprise that is unlikely to do much besides distort and crimp your portfolio management perspective. If this is what Hussman is teaching you, you need to find another teacher. :eek:

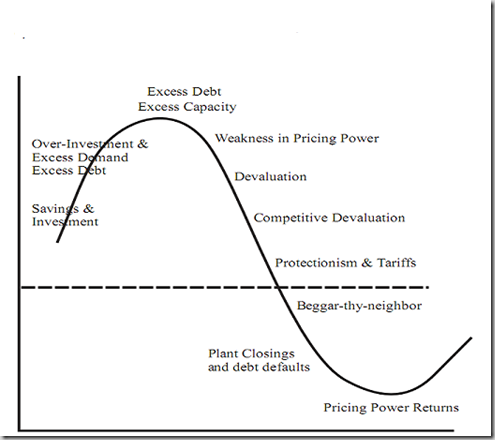

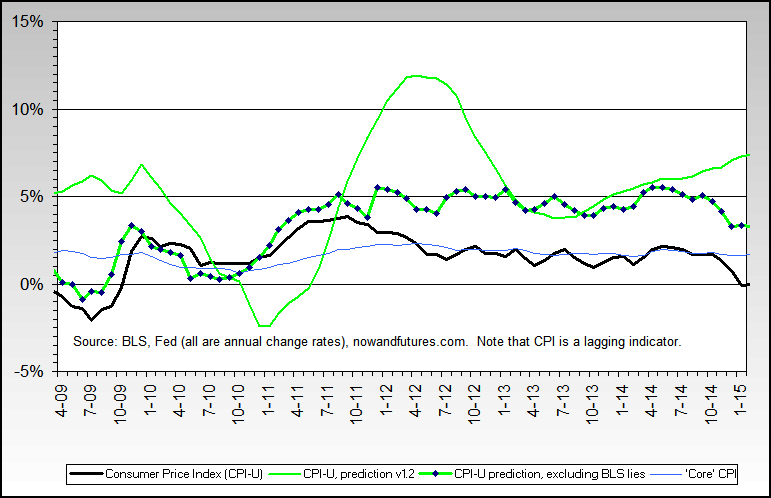

Seriously, there deep problems right from the get-go. One of which is competitive devaluation. Governments and their central banks can create currency at will, and those decisions are more often than not politically driven. Due to trade considerations and such, currencies have a tendency to move together. The situation is not that unlike with stocks. When a bear market is in force, most stocks will fall in price. When there is a bear market in currencies (global inflation) most will fall in value.

So what you are suggesting is tantamount to trying to pick the best stocks in a bear market. As you said yourself, the "least outstanding in an ugly contest." Nothing intrinsically immoral about that, I guess, but it is certainly trying to do an end-run around the asset allocation maxim just discussed.

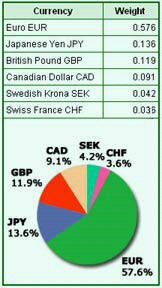

It may be not quite as obvious in the case of currencies as with stocks, because we use currency units themselves as units of measure. We might get a little too comfy with the tacit psychological suggestion implicit in the use of the USDX (dollar index) that it is some indicator of the absolute value of the dollar, and forget that it merely compares it to other things that are moving around themselves. We may even mistake a rise in the USDX for a rise in the value of the dollar.

This is not merely hypothetical. Just last year, the USDX spent much of the time in a rising trend. As every gold investor "knows", the price of gold moves counter to the dollar. Ergo, the price of gold "should" have fell.

But it didn't ... it soared. Analysts were flummoxed. But as Ayn Rand said, when you encounter a contradiction, examine your premises. In this case, the flawed premise was that the dollar was rising. No, the USDX was rising ... simply because the other currencies in the index had temporarily overtaken the dollar in the speed of their decline. The dollar was merely the "least outstanding in an ugly contest".

Competitive devaluation is not a theoretical phenomenon. China's yuan peg to the dollar is a very real and significant case in point.

Now seriously, what are the chances that in the event of a serious dollar decline, other global currencies will actually rise? That the US would enter accelerated inflation while the Eurozone, Asia and the rest all instituted deflation? That is the bet you would be taking ... mine is that hard money is far and away the best refuge in such a situation.

One further perspective: You apparently believe the US dollar will rise relative to the stock market - another way of saying that stock prices will fall (you say you have a zero stock position). Yet you worry it will fall relative to the rest of the world's currencies.

An extraordinarily remote conjunction of contingencies.

Originally posted by jk

Seriously, there deep problems right from the get-go. One of which is competitive devaluation. Governments and their central banks can create currency at will, and those decisions are more often than not politically driven. Due to trade considerations and such, currencies have a tendency to move together. The situation is not that unlike with stocks. When a bear market is in force, most stocks will fall in price. When there is a bear market in currencies (global inflation) most will fall in value.

So what you are suggesting is tantamount to trying to pick the best stocks in a bear market. As you said yourself, the "least outstanding in an ugly contest." Nothing intrinsically immoral about that, I guess, but it is certainly trying to do an end-run around the asset allocation maxim just discussed.

It may be not quite as obvious in the case of currencies as with stocks, because we use currency units themselves as units of measure. We might get a little too comfy with the tacit psychological suggestion implicit in the use of the USDX (dollar index) that it is some indicator of the absolute value of the dollar, and forget that it merely compares it to other things that are moving around themselves. We may even mistake a rise in the USDX for a rise in the value of the dollar.

This is not merely hypothetical. Just last year, the USDX spent much of the time in a rising trend. As every gold investor "knows", the price of gold moves counter to the dollar. Ergo, the price of gold "should" have fell.

But it didn't ... it soared. Analysts were flummoxed. But as Ayn Rand said, when you encounter a contradiction, examine your premises. In this case, the flawed premise was that the dollar was rising. No, the USDX was rising ... simply because the other currencies in the index had temporarily overtaken the dollar in the speed of their decline. The dollar was merely the "least outstanding in an ugly contest".

Competitive devaluation is not a theoretical phenomenon. China's yuan peg to the dollar is a very real and significant case in point.

Now seriously, what are the chances that in the event of a serious dollar decline, other global currencies will actually rise? That the US would enter accelerated inflation while the Eurozone, Asia and the rest all instituted deflation? That is the bet you would be taking ... mine is that hard money is far and away the best refuge in such a situation.

One further perspective: You apparently believe the US dollar will rise relative to the stock market - another way of saying that stock prices will fall (you say you have a zero stock position). Yet you worry it will fall relative to the rest of the world's currencies.

An extraordinarily remote conjunction of contingencies.

Suggests there is some underlying truth being converged in upon…

Suggests there is some underlying truth being converged in upon…

Comment