Announcement

Collapse

No announcement yet.

EJ Twitter thread on yield curve inversion

Collapse

X

-

Re: EJ Twitter thread on yield curve inversion

+1Originally posted by Slimprofits View PostThank you, Chomsky.

however, even if the yield curve is no longer a valid signal, there are plenty of other indicators pointing down for the global economy, with the u.s. not as far along the downslope.Last edited by jk; August 15, 2019, 11:21 AM.

Comment

-

Re: EJ Twitter thread on yield curve inversion

Flavor's definitely different. But there's a lot of weird debt out there.

On the personal side, mortgage debt is back up over 2008 peak levels, but only barely. Meanwhile non-mortgage personal debt has almost doubled in the last decade, from about $2.5T to about $4T. About a trillion of that is student loans. But the other half-trillion is mostly car loans, which quietly have shot up just as quickly.

Meanwhile, non-financial corporate debt has about doubled from about $3.5T to about $6.5T, about half of which is teetering just above junk, a good portion of which is just AT&T and Verizon, something like $0.2T for AT&T, representing ~80% of market cap at the moment, and $0.15T for Verizon, representing ~65% of market cap.

They obviously went no m&a sprees with the borrowed cash. But they jacked their debt loads up to the moon and what do they have to show for it over the last decade? Verizon has 30% more revenue, 30% more asset-value, and roughly 30,000 fewer employees, and they roughly had to triple their long-term debt to do it. Call it the rule of 3s for them. AT&T has 30% more revenue, 50% more asset-value, and roughly 40,000 fewer employees, and for that they had to triple their long-term debt. The debt-to-asset ratios are pretty close to 1:1. And they are shedding employees at a pretty good clip even as they gobble up assets. But it's taking a lot for a relatively modest revenue boost, and net-income remains pretty much flat.

Also we're seeing record smashing M&A activity. And over the last two decades, when you look at the breakdowns, it's not always where you think:

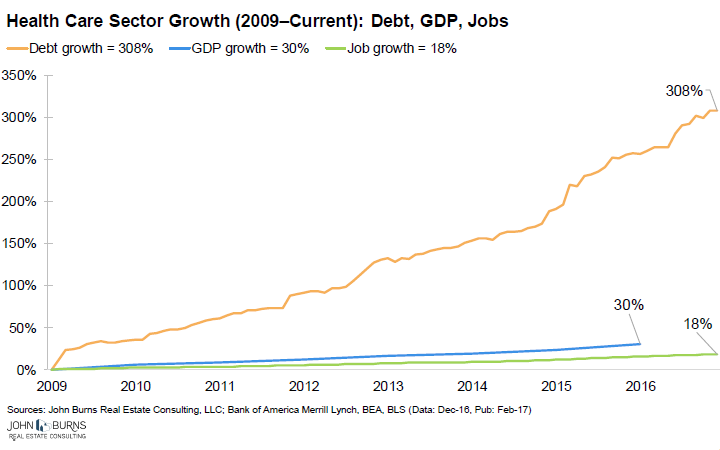

I'm always skeptical of M&A booms late in the cycle. Right after a downturn they might represent good value. But late in the expansion it's a feeding frenzy of levering up and buying high. Healthcare was up to 23% of deals by dollar last year. Healthcare M&A deals are increasingly a source of revenue for the big 3 (MorganS, GoldmanS, & JPMorgan), or course, maybe they'd rather call them 'consumer non-cyclical.' But it is what it is. The last 5 years have really kicked it into high gear. Healthcare M&A really went haywire in 2014. The story of the last 5 years has been a ~$2 trillion in healthcare M&A activity, largely debt-financed. It's to the point where healthcare corporate debt per capita is up around $15k per head in the US, 15 times higher than it was in 2000. I already talked about private buyouts, but we're talking another $0.2T in healthcare last year too. And in this particular sector, the US accounts for over half of the total worldwide action--meaning we're disproportionately exposed.

Sector-wide, we're talking tripling of debt, for 30% revenue growth, and 20% job growth. Healthcare is one of the only sectors where jobs grow as debt grows, along with software. But it's a similar situation where increasingly high debt levels are bringing increasingly fewer revenue returns.

That triple-your-debt to go on an M&A spree for 30% more revenue is very much the big corporate story of the last decade.

Comment

-

Re: EJ Twitter thread on yield curve inversion

How else can a CEO show revenue growth to keep his job when the economy goes soft?Originally posted by dcarrigg View Post

...That triple-your-debt to go on an M&A spree for 30% more revenue is very much the big corporate story of the last decade...

If money is cheap you can buy market share by buying up your competitors.

The pain of servicing that M&A debt is tomorrow's problem. When that day arrives you'll have fewer competitors and bigger top line gross sales which should make it all easier to deal with.

It's understandable even if it's misguided.

Comment

-

Re: EJ Twitter thread on yield curve inversion

Absolutely. I've just been trying to wrap my head around all the increased activity in the last couple years, in the healthcare sector specifically, and where the revenue ultimately comes from, and the limits of potential expansion. If it's a bubble, how big can it get, and what does it look like when it pops? Usually this kind of accelerated M&A and PE action feeds into it; hastens the process along.

Comment

-

Re: EJ Twitter thread on yield curve inversion

Combined, AT&T and Verizon have 275 million Americans. Too big to fail?

Everything I read about mergers in healthcare (like insurance companies merging with pharmacies) points out that all the big players want to get bigger, because when the next healthcare debate/debacle comes, they also want to sit at the table being viewed as too big to fail.

Comment

-

Re: EJ Twitter thread on yield curve inversion

Maybe bailouts is some kind of long-run hope here. I'm sure they'll come naturally begging as things go south, even if they hadn't planned to.Originally posted by Thailandnotes View PostCombined, AT&T and Verizon have 275 million Americans. Too big to fail?

Everything I read about mergers in healthcare (like insurance companies merging with pharmacies) points out that all the big players want to get bigger, because when the next healthcare debate/debacle comes, they also want to sit at the table being viewed as too big to fail.

When they busted up ma bell in 1982, they broke it into six pieces. NYNEX, which is now Verizon. Pacific Telesis, which is now AT&T again, Ameritech, which is now AT&T again, Bell Atlantic, which is now Verizon, Southwestern Bell, which is now AT&T again, Bell South, which is now AT&T again, and US West, the only one not owned by either. Meanwhile, they have the new cell divisions and Time-Warner. Certainly it's bigger now than when it was busted up.

Let's hope that little bit of history is enough to plant the idea in a few people's brains if/when the beggars come looking for even more handouts.

Comment

-

Re: EJ Twitter thread on yield curve inversion

Unless AT&T and Verizon engage in genuine gambling where they speculate in financial instruments (e.g.; options trading, futures trading, or buying junk paper in hopes of making massive capital gains), I can't imagine it ever getting to the point where they would need (they would always *want*) government bailout money. AT&T under Michael Armstrong ran up a tremendously large debt during the dot-com bubble (I remember it being around $60B to $80B). When the dot-com bubble popped, AT&T was forced to puke up most or all the acquisitions it had made. I don't see why AT&T couldn't be forced to once again regurgitate some of its acquisitions if market conditions get rough. DirecTV and Time-Warner appear to be two assets that AT&T could be forced to divest if it needed to raise cash.Originally posted by Thailandnotes View PostCombined, AT&T and Verizon have 275 million Americans. Too big to fail?

Everything I read about mergers in healthcare (like insurance companies merging with pharmacies) points out that all the big players want to get bigger, because when the next healthcare debate/debacle comes, they also want to sit at the table being viewed as too big to fail.

Comment

-

Re: EJ Twitter thread on yield curve inversion

FWIW, seems to me they're kind of in two different spots. AT&T is gobbling up IP and basically consolidating the Latin American market from Mexico down to Tierra del Fuego. I imagine we're in a position where very soon there will be 5 or 6 media conglomerate streaming services and they'll pull all their content from the Netflix/Amazon/Hulus of the world and vertically integrate the content delivery. Verizon doesn't seem to be playing that game. They've been gobbling up ISPs and wireless spectrum and 5G type stuff, along with pretty big plays at vehicle fleet autocar nonsense. Meanwhile, data center M&A activity has been ramping up at breakneck speed; they must see another potential power choke point there.

So it's ~$200B for AT&T now. And some of it is really long-dated. But they've got some big tranches coming up. Maybe $20B or so comes due in 2020. 2021's a little easier, about half that. $20B again due in 2022. And then about $10B per year out to 2030. Most of it at about 6 or 7%. Only $3-4B total is tagged onto DirecTV and Time-Warner. So they could offload them to raise cash if necessary. They had net income of about $19B in 2018. So I figure things are gonna get a bit tight in the near-term even if the markets at large don't go south.

Word on the street is the next move is to merge DirecTV with Dish Network and make a single company monopoly on satellite. Maybe not so much a concern in most of the US. Probably a much bigger deal in South America. And Dish just bought Boost Mobile and most of the 800MHz stuff off Sprint-T-Mobile last month, I figure to sweeten the pot for an AT&T buyout.

Comment

-

Re: EJ Twitter thread on yield curve inversion

Sorry, should have been clear: this was me operating under the presumption that the recent credit downgrades would make borrowing more expensive in the near-term. Hovering around BBB/Baa2 now. The combo of high dividend yield + weak credit rating + big debt tranche coming due makes me suspect that dividend won't be so high for very long.

Comment

-

Re: EJ Twitter thread on yield curve inversion

yeah, dividend cut seems likely. re their bonds- i think the question is when/whether we hit the bbb apocalypse. e.g. iirc ge has $100billion in bbb debt. given recent revelations/accusations they could be downrated, causing forced selling by funds and pension plans and setting off snowballing selling in the corp bond market.Originally posted by dcarrigg View PostSorry, should have been clear: this was me operating under the presumption that the recent credit downgrades would make borrowing more expensive in the near-term. Hovering around BBB/Baa2 now. The combo of high dividend yield + weak credit rating + big debt tranche coming due makes me suspect that dividend won't be so high for very long.

Comment

-

Re: EJ Twitter thread on yield curve inversion

Originally posted by Chomsky View Post

Jeffrey Snider thinks the yield curve inversion does tell us something.

---

The Bond Market Keeps Telling Us How Clueless Global Officials Are

By Jeffrey Snider

August 16, 2019

What is it about term premiums? If you were to ask any Economist, they would tell you a term premium is the additional return a bond investor demands in order to lend money for a longer period of time. A premium for more term. Even the US government must pay. Should the government wish to sell, say, a three-year note, whomever is buying it will demand some additional yield above what the government offers on a two-year security.

It sounds simple and straightforward, easily intuitive.

Irving Fisher long ago decomposed bond yields into these kinds of constituent pieces. This Fisherian deconstruction is accepted as three parts: term premiums are one, inflation expectations another, and the anticipated path of short-term money rates the last.

You cannot observe a term premium – though it seems like it should be a matter of simple mathematics. Take the yield on the two-year note and subtract it from the yield on the three-year; voila, term premium.

The world, and the bond market, is much more complicated than that. What any bond investor might be anticipating in Year 2 could be very different from what any bond investor might be thinking about Year 3. A term premium alone might explain yield curve differences, or shape, but those other factors play a key role, too.

If you and many others like you begin to feel nervous about economic or financial prospects in the future, you might begin to change how you invest in bonds. A growing market consensus for lower inflation for whatever reason or reasons which might hit between Year 1 and Year 4 would alter the very structure of the curve and the yields which fall within that time segment.

Therefore, if term premiums remained the same, that is you still demand some extra compensation for being locked into a similar instrument for an additional year, and the expected path of short-term interest rates is the same, nothing more than lower inflation expectations would suggest perhaps a lower interest rate at the three-year maturity than otherwise.

That wouldn’t necessarily mean the nominal yield becomes less; it could be the case where the upward slope of the curve between the two-year and three-year maturities is significantly flatter. If you relied on the simple mathematics, you’d be conflating issues. What might look like a lower term premium is instead lower embedded inflation expectations.

What happens, though, is that lower inflation expectations never materialize in a vacuum. Usually oil prices are involved in setting them, sure, but so is some detailed sense of why generalized inflation might weaken in discrete time periods.

This sort of thing isn’t usually associated with good overall economic conditions, so in addition to reevaluating inflation expectations bond investors are probably going to take a second look at their views on how they think short-term rates will unfold. If there is a risk inflation significantly disappoints, then there must also be some risk that a central bank might be forced to respond to what’s going on. Perhaps a rate cut maybe two.

Thus, as inflation expectations soften it stands to reason expectations about the future path of short-term interest rates would, as well. The more convinced bond investors might be of the former, the more they would question the latter.

And it works both ways. If you start from the position that the economy is more likely to be bad in Year 3 as opposed to Year 2, bad enough the central bank will have to take action, that’s probably not a conducive environment for inflationary pressures, either. It isn’t necessarily a single bloc inside the nominal yield, but the inflation expectations and short-term rate components do coincide more than not.

What also happens more than not is how central bankers see themselves and their work. It is always and foreverassumed that monetary policies are effective at both inflation and economy. Convention says the Fed does something and therefore the bond market is merely Pavlovian in its response.

Take QE, for example. In the official handbook this is absolutely effective stuff; best of the best. Since no one would ever fight the Fed, and no one ever does in the econometric models the Fed uses, bond investors are modeled to react to QE quite predictably. Their expectations for inflation will rise as will their view of the future path of short-term interest rates.

The bond market, we are told, looks upon powerful monetary stimulus as powerful monetary stimulus, the end result of powerful monetary stimulus being an inflationary breakout which, given the current environment, should mean a little more inflation and higher short-term rates (which are only to make sure inflation is a little rather than a lot more).

Put those two pieces together with natural term premiums it becomes a steepening yield curve rising nominally all across the maturities. A sight to behold, an end to the lost decade.

That isn’t what happened, of course. Yields never rose that much during what were supposed to have been the best of times (2017 and the first half of 2018). Since last November, you might have noticed they’ve been falling rather precipitously.

Ben Bernanke, Janet Yellen, and now Jay Powell all still believe QE was powerful monetary stimulus, that it had very positive effects on the economy, and that the end result was and still will be a very definite, sustained pick up and acceleration in growth and inflation. That interpretation has already led to (some) rate hikes as everyone had planned.

Under their dogmatic analyses, the bond market absolutely believes as they do – how could it not? But that leaves them with a key conundrum. How can interest rates be falling and the curve flattening, distorting, and inverting?

If you are stuck on QE being awesomely effective, then you are left only with one possibility to attempt an answer. By believing in QE and therefore the economy of QE, your inflation expectations must still be rising and higher, your expected path for short-term interest rates must be rising and higher, which means the only thing left to account for market behavior is the plug line – term premiums.

Should nominal rates fall far enough, and you stubbornly refuse to change your mind about the other two components, then you’ll have to concede that term premiums must then be negative. That’s the only way to maintain the positive view of the economy and QE in an environment that doesn’t really fit the positive view of the economy and QE.

What is a negative term premium?

Like a negative swap spread, for instance, it is utter nonsense. But at least in the case of an interest rate swap, the nonsense is valuable (since it tells us there must be a grave imbalance in the marketplace itself). A negative term premium, by contrast, is nothing more than full-blown denial.

As you’ve probably heard, the US Treasury yield curve inverted a couple days ago. While that’s technically true, it’s not exactly true by what’s been omitted. A specific part of the yield curved inverted – the comparison of the 2-year note with the benchmark 10-year bond. Investors buying and holding (meaning not selling) the latter are accepting a little less in yield than those buying and holding the former.

For many people, this a clear recession signal – and, sadly, the only reason the public pays attention to the yield curve.

While its true the 2s10s just inverted, the yield curve has been inverted in other places for far longer – going back to the end of last year, in fact. It had been controversially flattening out for even longer that that – going back to the end of the year before last, in fact.

I write it was controversial only because central bankers and Economists refuse to budge on their Fisherian deconstruction. Janet Yellen just the other day said pay no attention to the yield curve inversion (2s10s), it’s artificial.

“The reason for that is there are a number of factors other than market expectations about the future path of interest rates that are pushing down long-term yields.”

It’s all in the term premiums, they claim. It can’t possibly be either or both of those other two constituent pieces.

But why?

While there is no market indication or price for term premiums, there sure as hell are for inflation expectations and the market-priced future path for short-term interest rates. The first one is called TIPS, the second eurodollar futures. They are directly related to these core concepts.

I’m sure you can guess how those markets have been trading. In 2017 and early 2018 when Janet Yellen was supposed to be at her apex, she was instead fending off questions about the curve. At her final press conference as Chairman, in December 2017, she was asked about it:

“The yield curve has flattened some as we have raised short rates. It mainly—the flattening yield curve mainly reflects higher short-term rates…Well, right now the term premium is estimated to be quite low, close to zero, and that means that, structurally—and this can be true going forward—that the yield curve is likely to be flatter than it’s been in the past. And so it could more easily invert.”

If term premiums had been more positive than they were judged to be at that point, by her, then interest rates especially at the longer end of the curve would’ve gone up much more and instead of flattening it would’ve maintained its shape if not steepened (before flattening at some level nearer to a normal interest rate environment). But why did (does) she believe term premiums were (are) so low or even negative?

R-star.

Economists have so warped their view of the world that the only way for it to make any sense to them is for a flat and now inverted yield curve to be something other than a flat and inverted yield curve. Having to reverse engineer how QE and low interest rates were not total failures, and that the bond market isn’t actually completely disagreeing with the Fed on every salient point, pricing a very different set of circumstances, they have to resort to even more tortured rationalizations and denials.

It only begins with circular logic. Back to Yellen at that key moment in December 2017:

“So I think the fact the term premium is so low and the yield curve is generally flatter is an important factor to consider. Now, I think it’s also important to realize that market participants are not expressing heightened concern about the decline of the term premium, and, when asked directly about the odds of recession, they see it as low, and I would concur with that judgment.”

Wait a minute; the fact that the yield curve was flattening so precipitously as it had been doing was the market expressing concern. But Yellen says it wasn’t concern because term premiums were the reason it was flattening in the first place. So, falling term premiums flattened the curve, and usually a flat curve is a warning but not in this case because the curve was flattened due to term premiums.

And since low or negative term premiums are the presumed consequence of a low R-star, nothing-to-see-here. But why the low R-star?

QE was supposed to have produced or at least have assured a full and complete recovery from the Great “Recession” and the somehow Global Financial Crisis. It didn’t. Not even Ben Bernanke would admit there has been a full and complete recovery. From economic growth to the labor participation problem, the economy on this side of 2008 is stunted by every single measure. The question is why.

Central bankers, as you would expect, refuse to believe it was because a monetary event, the GFC, was met with an ineffective monetary response (QE and ZIRP). The very fact there was a GFC in the first place is relevant (in the bond market as well as this discussion) in setting our expectations here.

The only way around that possibility is to claim that QE did the best it could have – that if the economy is different after 2008 it must be because of structural factors beyond the grasp of any policy anywhere. R-star means QE didn’t fail, it actually succeeded but because of retiring Baby Boomers, drug-addicted unemployable workers, and lazy Americans who refuse to go back to school and learn to code, the results don’t show up in the way Ben Bernanke had promised way back when.

Don’t blame the Fed; it’s your fault.

And the bond market is only on their side when they cast term premiums in this way.

Except, no. We have all sorts of market evidence, deep, liquid, and sophisticated markets for TIPS and eurodollar futures that expose term premiums for what they are – central bankers rationalizing their own delusions in order to avoid the only factor that explains all the facts including interest rate behavior.

They’ve got the monetary system all wrong.

While Janet Yellen was rewriting the flat yield curve in December 2017, the eurodollar futures curve was also flattening because it was saying the market didn’t expect the Fed to complete nearly as many rate hikes. Something would surely go wrong first.

In June 2018, the eurodollar futures curve inverted; that something was much closer. Well over a year ago, when everyone said there was no way it would happen, this market which prices the expected path of future interest rates correctly surmised way ahead of time there would be rate cuts instead.

For its assigned part, the TIPS market had never judged inflation as some deep threat no matter how much hysteria was unleashed over the unemployment rate. Since last May 29, expectations first had become more neutral before last November falling and then falling some more this year.

The flat curve was exactly what the flat curve had always been – a warning that the financial risks were substantial and could tip the balance from a reflationary economy struggling to break out back toward a deflationary one which is its true underlying baseline condition. It even had the added benefit of telling you exactly why (the interest rate fallacy).

The inverted curve is simply the market saying to Janet Yellen, I told you so but like 2007 you refused to listen.

Therefore, the reason that the yield on the three-year (or ten-year) is less than the yield on the two-year (or one-year) is because the market foresees a lot of bad things developing in the near term and, perhaps more importantly, the consequences of those developments lingering into the intermediate term and beyond. The kinds of negative factors that will lead to much less inflation and lower short-term interest rates. The same risks – now realized - that kept yields low and the curve flat when Yellen was deluding herself and the public about term premiums and R-star almost two years ago.

Because all this term premium stuff is total garbage, obvious nonsense, of course Janet Yellen this week hedged on the question of recession.

“I think the U.S. economy has enough strength to avoid that, but the odds have clearly risen and they’re higher than I’m frankly comfortable with.”

Way to stick to your guns, Janet.

Recapping the former Chair: she thinks the yield curve isn’t what it seems to be, it isn’t what it always was – but is also worried it might be. That’s the problem with being forced into looking at everything backward. No matter how much you try to convince yourself that R-stars and term premiums are meaningful and righteous assessments, you can’t ever shake that nagging feeling that the thing really is what it is.

Economists don’t understand bonds because they don’t want to understand bonds; the bond market has been the one constant throughout telling the world officials really have no idea what they are doing.

Jeffrey Snider is the Chief Investment Strategist of Alhambra Investment Partners, a registered investment advisor.

https://www.realclearmarkets.com/art...re_103859.html

Comment

Comment