New York Times Pushes False Narrative on the Wall Street Crash of 2008

According to the OCC, Just Four Banks (JPMorgan Chase, Citigroup, Bank of America and Goldman Sachs) Hold 91.3 Percent of All Derivatives Held By More Than 6,000 U.S. Banks as of the First Quarter of 2015

By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: August 3, 2015

William D. Cohan has joined Paul Krugman and Andrew Ross Sorkin at the New York Times in pushing the patently false narrative that the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act in 1999 had next to nothing to do with the epic Wall Street collapse of 2008 and the greatest economic calamity since the Great Depression.

The New York Times has already admitted on its editorial page that it was dead wrong to have pushed for the repeal of Glass-Steagall but now it’s dirtying its hands again by publishing all of these false narratives about what actually happened.

In a July 30 column, Cohan ridicules Senators Elizabeth Warren and John McCain over their introduction of legislation to restore the Glass-Steagall Act to separate insured deposit banks from their gambling casino cousins, Wall Street investment banks. The Senators are being joined in their call to restore Glass-Steagall by a growing number of Presidential aspirants, including Senator Bernie Sanders and former Governor of Maryland, Martin O’Malley, both running as Democrats.

Hillary Clinton, another Democratic presidential hopeful whose husband, Bill Clinton, signed the bill during his presidency that repealed Glass-Steagall, does not see the need to restore Glass-Steagall, leading Cohan to make this observation:

“Mrs. Clinton is right. Despite the relentless rhetoric, the fact that commercial banks are in the investment banking business and investment banks are in the commercial banking business had almost nothing to do with causing the financial crisis of 2008.”

The “almost nothing” Cohan refers to was the colossal collapse of the county’s largest bank at the time, Citigroup, which saw its share price drop to 99 cents (a penny stock) with the taxpayer being forced to infuse the greatest bailout in U.S. history into this bank: $45 billion in equity; over $300 billion in asset guarantees; and a cumulative total of over $2 trillion in super-cheap revolving loans from the Federal Reserve that lasted for years to resuscitate its insolvent carcass.

Cohan sheepishly concedes in his column that Citigroup “while a big commercial bank, would surely have failed without its government rescue, in large part because of the behavior of its investment bankers.”

Insiders in government at the time of the crash believe that Citigroup was at the core of the 2008 crash. According to the regulator of national banks, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), Citigroup’s serious problems began in the summer of 2007. Media reports about its drastic need for a bailout fund, which didn’t fly but was going to be called the SuperSIV, began in the fall of 2007. We wrote extensively about Citigroup’s desperate situation in November 2007.

The other problems came long after Citigroup began to teeter. Bear Stearns received an emergency infusion from the Fed on March 14, 2008 and was bought out by JPMorgan Chase on March 16, 2008. Lehman Brothers failed on September 15, 2008; AIG, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were all rescued by the government in September 2008.

Sheila Bair, the chair of the FDIC at the time of the crisis, spoke with Andrew Cockburn for his April expose on Citigroup in Harper’s Magazine. Bair said the multi-trillion-dollar bailouts were largely about Citigroup: “The over-the-top generosity was driven in part by the desire to help Citi and cover up its outlier status,” says Bair. Cockburn adds: “In other words, everyone was showered with money to distract attention from the one bankrupt institution that was seriously in need of it.”

It was Citigroup’s intractable shakiness and Wall Street’s inability to decipher who had counterparty exposure to it that seized up lending across Wall Street. On July 13, 2008, two months before the collapse of Lehman and AIG, Bloomberg News ran a story about Citigroup’s massive off-balance sheet exposures, including a chart which stated: “Citigroup keeps $1.1 trillion of assets in off-balance-sheet entities, an amount equivalent to half the company’s assets and more than 12 times its dwindling market value.” Let that sink in for a moment: its off-balance sheet exposure was 12 times its total market capitalization. You cannot imagine the instant vaporization of confidence this revelation had across Wall Street.

Eight days later, Bloomberg News was back to reporting on the abysmal situation at Citigroup with the headline: “Citigroup Unravels as Reed Regrets Universal Model.” The article said that the bank “is mired in a crisis” with “$54.6 billion in writedowns and credit costs.” The article further notes that Citigroup “made some of the biggest bets in the subprime lending debacle,” it had to “bail out at least nine off-balance-sheet investment funds in the past year” and “defaults are rising.”

The official report on the crisis, the Financial Crisis Inquiry Report, also called out Citigroup as a pivotal player in the crash, writing:

“More than other banks, Citigroup held assets off of its balance sheet, in part to hold down capital requirements. In 2007, even after bringing $80 billion worth of assets on balance sheet, substantial assets remained off. If those had been included, leverage in 2007 would have been 48:1…”

Cohan’s most egregious fallacy is when he writes the following:

“The problem on Wall Street is not the size of the banks, their concentration of assets or the businesses they choose to be in. The problem on Wall Street remains one of improper incentives. When people are rewarded to take big risks with other people’s money, that’s exactly what they will do.”

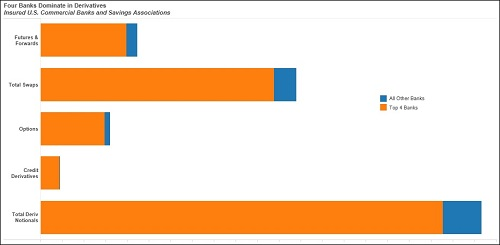

There is a wealth of stunning proof (like the chart above) that the biggest risk is asset concentration at four banks, along with insane levels of derivatives concentration. The OCC reported that as of the first quarter of 2015, JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, Goldman Sachs (yes, it owns an insured bank) and the bailed out Citigroup hold 91.3 percent of all derivatives on the books of all 6,419 insured banks. The total amount of derivatives is a stunning $203.1 trillion, meaning that just these four banks, seven years after the greatest financial collapse since the Great Depression, are still holding $185 trillion in derivatives.

If that’s not high risk concentration, we don’t know what is. If that’s not failed financial reform, we don’t know what is.

According to the OCC, Just Four Banks (JPMorgan Chase, Citigroup, Bank of America and Goldman Sachs) Hold 91.3 Percent of All Derivatives Held By More Than 6,000 U.S. Banks as of the First Quarter of 2015

By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: August 3, 2015

William D. Cohan has joined Paul Krugman and Andrew Ross Sorkin at the New York Times in pushing the patently false narrative that the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act in 1999 had next to nothing to do with the epic Wall Street collapse of 2008 and the greatest economic calamity since the Great Depression.

The New York Times has already admitted on its editorial page that it was dead wrong to have pushed for the repeal of Glass-Steagall but now it’s dirtying its hands again by publishing all of these false narratives about what actually happened.

In a July 30 column, Cohan ridicules Senators Elizabeth Warren and John McCain over their introduction of legislation to restore the Glass-Steagall Act to separate insured deposit banks from their gambling casino cousins, Wall Street investment banks. The Senators are being joined in their call to restore Glass-Steagall by a growing number of Presidential aspirants, including Senator Bernie Sanders and former Governor of Maryland, Martin O’Malley, both running as Democrats.

Hillary Clinton, another Democratic presidential hopeful whose husband, Bill Clinton, signed the bill during his presidency that repealed Glass-Steagall, does not see the need to restore Glass-Steagall, leading Cohan to make this observation:

“Mrs. Clinton is right. Despite the relentless rhetoric, the fact that commercial banks are in the investment banking business and investment banks are in the commercial banking business had almost nothing to do with causing the financial crisis of 2008.”

The “almost nothing” Cohan refers to was the colossal collapse of the county’s largest bank at the time, Citigroup, which saw its share price drop to 99 cents (a penny stock) with the taxpayer being forced to infuse the greatest bailout in U.S. history into this bank: $45 billion in equity; over $300 billion in asset guarantees; and a cumulative total of over $2 trillion in super-cheap revolving loans from the Federal Reserve that lasted for years to resuscitate its insolvent carcass.

Cohan sheepishly concedes in his column that Citigroup “while a big commercial bank, would surely have failed without its government rescue, in large part because of the behavior of its investment bankers.”

Insiders in government at the time of the crash believe that Citigroup was at the core of the 2008 crash. According to the regulator of national banks, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), Citigroup’s serious problems began in the summer of 2007. Media reports about its drastic need for a bailout fund, which didn’t fly but was going to be called the SuperSIV, began in the fall of 2007. We wrote extensively about Citigroup’s desperate situation in November 2007.

The other problems came long after Citigroup began to teeter. Bear Stearns received an emergency infusion from the Fed on March 14, 2008 and was bought out by JPMorgan Chase on March 16, 2008. Lehman Brothers failed on September 15, 2008; AIG, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were all rescued by the government in September 2008.

Sheila Bair, the chair of the FDIC at the time of the crisis, spoke with Andrew Cockburn for his April expose on Citigroup in Harper’s Magazine. Bair said the multi-trillion-dollar bailouts were largely about Citigroup: “The over-the-top generosity was driven in part by the desire to help Citi and cover up its outlier status,” says Bair. Cockburn adds: “In other words, everyone was showered with money to distract attention from the one bankrupt institution that was seriously in need of it.”

It was Citigroup’s intractable shakiness and Wall Street’s inability to decipher who had counterparty exposure to it that seized up lending across Wall Street. On July 13, 2008, two months before the collapse of Lehman and AIG, Bloomberg News ran a story about Citigroup’s massive off-balance sheet exposures, including a chart which stated: “Citigroup keeps $1.1 trillion of assets in off-balance-sheet entities, an amount equivalent to half the company’s assets and more than 12 times its dwindling market value.” Let that sink in for a moment: its off-balance sheet exposure was 12 times its total market capitalization. You cannot imagine the instant vaporization of confidence this revelation had across Wall Street.

Eight days later, Bloomberg News was back to reporting on the abysmal situation at Citigroup with the headline: “Citigroup Unravels as Reed Regrets Universal Model.” The article said that the bank “is mired in a crisis” with “$54.6 billion in writedowns and credit costs.” The article further notes that Citigroup “made some of the biggest bets in the subprime lending debacle,” it had to “bail out at least nine off-balance-sheet investment funds in the past year” and “defaults are rising.”

The official report on the crisis, the Financial Crisis Inquiry Report, also called out Citigroup as a pivotal player in the crash, writing:

“More than other banks, Citigroup held assets off of its balance sheet, in part to hold down capital requirements. In 2007, even after bringing $80 billion worth of assets on balance sheet, substantial assets remained off. If those had been included, leverage in 2007 would have been 48:1…”

Cohan’s most egregious fallacy is when he writes the following:

“The problem on Wall Street is not the size of the banks, their concentration of assets or the businesses they choose to be in. The problem on Wall Street remains one of improper incentives. When people are rewarded to take big risks with other people’s money, that’s exactly what they will do.”

There is a wealth of stunning proof (like the chart above) that the biggest risk is asset concentration at four banks, along with insane levels of derivatives concentration. The OCC reported that as of the first quarter of 2015, JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, Goldman Sachs (yes, it owns an insured bank) and the bailed out Citigroup hold 91.3 percent of all derivatives on the books of all 6,419 insured banks. The total amount of derivatives is a stunning $203.1 trillion, meaning that just these four banks, seven years after the greatest financial collapse since the Great Depression, are still holding $185 trillion in derivatives.

If that’s not high risk concentration, we don’t know what is. If that’s not failed financial reform, we don’t know what is.

Comment