Why Central Banks Should Give Money Directly to the People

By Mark Blyth and Eric Lonergan

In the decades following World War II, Japan’s economy grew so quickly and for so long that experts came to describe it as nothing short of miraculous. During the country’s last big boom, between 1986 and 1991, its economy expanded by nearly $1 trillion. But then, in a story with clear parallels for today, Japan’s asset bubble burst, and its markets went into a deep dive. Government debt ballooned, and annual growth slowed to less than one percent. By 1998, the economy was shrinking.

That December, a Princeton economics professor named Ben Bernanke argued that central bankers could still turn the country around. Japan was essentially suffering from a deficiency of demand: interest rates were already low, but consumers were not buying, firms were not borrowing, and investors were not betting. It was a self-fulfilling prophesy: pessimism about the economy was preventing a recovery. Bernanke argued that the Bank of Japan needed to act more aggressively and suggested it consider an unconventional approach: give Japanese households cash directly. Consumers could use the new windfalls to spend their way out of the recession, driving up demand and raising prices.

As Bernanke made clear, the concept was not new: in the 1930s, the British economist John Maynard Keynes proposed burying bottles of bank notes in old coal mines; once unearthed (like gold), the cash would create new wealth and spur spending. The conservative economist Milton Friedman also saw the appeal of direct money transfers, which he likened to dropping cash out of a helicopter. Japan never tried using them, however, and the country’s economy has never fully recovered. Between 1993 and 2003, Japan’s annual growth rates averaged less than one percent.

Today, most economists agree that like Japan in the late 1990s, the global economy is suffering from insufficient spending, a problem that stems from a larger failure of governance. Central banks, including the U.S. Federal Reserve, have taken aggressive action, consistently lowering interest rates such that today they hover near zero. They have also pumped trillions of dollars’ worth of new money into the financial system. Yet such policies have only fed a damaging cycle of booms and busts, warping incentives and distorting asset prices, and now economic growth is stagnating while inequality gets worse. It’s well past time, then, for U.S. policymakers -- as well as their counterparts in other developed countries -- to consider a version of Friedman’s helicopter drops. In the short term, such cash transfers could jump-start the economy. Over the long term, they could reduce dependence on the banking system for growth and reverse the trend of rising inequality. The transfers wouldn’t cause damaging inflation, and few doubt that they would work. The only real question is why no government has tried them.

Instead of trying to drag down the top, governments should boost the bottom.

EASY MONEY

In theory, governments can boost spending in two ways: through fiscal policies (such as lowering taxes or increasing government spending) or through monetary policies (such as reducing interest rates or increasing the money supply). But over the past few decades, policymakers in many countries have come to rely almost exclusively on the latter. The shift has occurred for a number of reasons. Particularly in the United States, partisan divides over fiscal policy have grown too wide to bridge, as the left and the right have waged bitter fights over whether to increase government spending or cut tax rates. More generally, tax rebates and stimulus packages tend to face greater political hurdles than monetary policy shifts. Presidents and prime ministers need approval from their legislatures to pass a budget; that takes time, and the resulting tax breaks and government investments often benefit powerful constituencies rather than the economy as a whole. Many central banks, by contrast, are politically independent and can cut interest rates with a single conference call. Moreover, there is simply no real consensus about how to use taxes or spending to efficiently stimulate the economy.

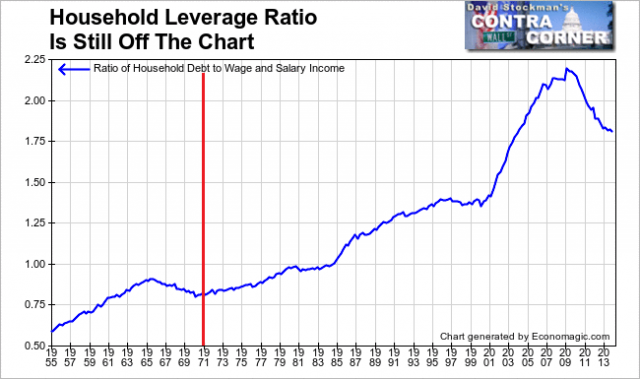

Steady growth from the late 1980s to the early years of this century seemed to vindicate this emphasis on monetary policy. The approach presented major drawbacks, however. Unlike fiscal policy, which directly affects spending, monetary policy operates in an indirect fashion. Low interest rates reduce the cost of borrowing and drive up the prices of stocks, bonds, and homes. But stimulating the economy in this way is expensive and inefficient, and can create dangerous bubbles -- in real estate, for example -- and encourage companies and households to take on dangerous levels of debt.

That is precisely what happened during Alan Greenspan’s tenure as Fed chair, from 1997 to 2006: Washington relied too heavily on monetary policy to increase spending. Commentators often blame Greenspan for sowing the seeds of the 2008 financial crisis by keeping interest rates too low during the early years of this century. But Greenspan’s approach was merely a reaction to Congress’ unwillingness to use its fiscal tools. Moreover, Greenspan was completely honest about what he was doing. In testimony to Congress in 2002, he explained how Fed policy was affecting ordinary Americans:

"Particularly important in buoying spending [are] the very low levels of mortgage interest rates, which [encourage] households to purchase homes, refinance debt and lower debt service burdens, and extract equity from homes to finance expenditures. Fixed mortgage rates remain at historically low levels and thus should continue to fuel reasonably strong housing demand and, through equity extraction, to support consumer spending as well.

"Of course, Greenspan’s model crashed and burned spectacularly when the housing market imploded in 2008. Yet nothing has really changed since then. The United States merely patched its financial sector back together and resumed the same policies that created 30 years of financial bubbles. Consider what Bernanke, who came out of the academy to serve as Greenspan’s successor, did with his policy of “quantitative easing,” through which the Fed increased the money supply by purchasing billions of dollars’ worth of mortgage-backed securities and government bonds. Bernanke aimed to boost stock and bond prices in the same way that Greenspan had lifted home values. Their ends were ultimately the same: to increase consumer spending.

The overall effects of Bernanke’s policies have also been similar to those of Greenspan’s. Higher asset prices have encouraged a modest recovery in spending, but at great risk to the financial system and at a huge cost to taxpayers. Yet other governments have still followed Bernanke’s lead. Japan’s central bank, for example, has tried to use its own policy of quantitative easing to lift its stock market. So far, however, Tokyo’s efforts have failed to counteract the country’s chronic underconsumption. In the eurozone, the European Central Bank has attempted to increase incentives for spending by making its interest rates negative, charging commercial banks 0.1 percent to deposit cash. But there is little evidence that this policy has increased spending.

China is already struggling to cope with the consequences of similar policies, which it adopted in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. To keep the country’s economy afloat, Beijing aggressively cut interest rates and gave banks the green light to hand out an unprecedented number of loans. The results were a dramatic rise in asset prices and substantial new borrowing by individuals and financial firms, which led to dangerous instability. Chinese policymakers are now trying to sustain overall spending while reducing debt and making prices more stable. Like other governments, Beijing seems short on ideas about just how to do this. It doesn’t want to keep loosening monetary policy. But it hasn’t yet found a different way forward.

The broader global economy, meanwhile, may have already entered a bond bubble and could soon witness a stock bubble. Housing markets around the world, from Tel Aviv to Toronto, have overheated. Many in the private sector don’t want to take out any more loans; they believe their debt levels are already too high. That’s especially bad news for central bankers: when households and businesses refuse to rapidly increase their borrowing, monetary policy can’t do much to increase their spending. Over the past 15 years, the world’s major central banks have expanded their balance sheets by around $6 trillion, primarily through quantitative easing and other so-called liquidity operations. Yet in much of the developed world, inflation has barely budged.

To some extent, low inflation reflects intense competition in an increasingly globalized economy. But it also occurs when people and businesses are too hesitant to spend their money, which keeps unemployment high and wage growth low. In the eurozone, inflation has recently dropped perilously close to zero. And some countries, such as Portugal and Spain, may already be experiencing deflation. At best, the current policies are not working; at worst, they will lead to further instability and prolonged stagnation.

MAKE IT RAIN

Governments must do better. Rather than trying to spur private-sector spending through asset purchases or interest-rate changes, central banks, such as the Fed, should hand consumers cash directly. In practice, this policy could take the form of giving central banks the ability to hand their countries’ tax-paying households a certain amount of money. The government could distribute cash equally to all households or, even better, aim for the bottom 80 percent of households in terms of income. Targeting those who earn the least would have two primary benefits. For one thing, lower-income households are more prone to consume, so they would provide a greater boost to spending. For another, the policy would offset rising income inequality.

Such an approach would represent the first significant innovation in monetary policy since the inception of central banking, yet it would not be a radical departure from the status quo. Most citizens already trust their central banks to manipulate interest rates. And rate changes are just as redistributive as cash transfers. When interest rates go down, for example, those borrowing at adjustable rates end up benefiting, whereas those who save -- and thus depend more on interest income -- lose out.

Most economists agree that cash transfers from a central bank would stimulate demand. But policymakers nonetheless continue to resist the notion. In a 2012 speech, Mervyn King, then governor of the Bank of England, argued that transfers technically counted as fiscal policy, which falls outside the purview of central bankers, a view that his Japanese counterpart, Haruhiko Kuroda, echoed this past March. Such arguments, however, are merely semantic. Distinctions between monetary and fiscal policies are a function of what governments ask their central banks to do. In other words, cash transfers would become a tool of monetary policy as soon as the banks began using them.

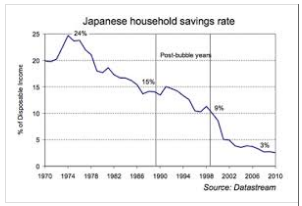

Other critics warn that such helicopter drops could cause inflation. The transfers, however, would be a flexible tool. Central bankers could ramp them up whenever they saw fit and raise interest rates to offset any inflationary effects, although they probably wouldn’t have to do the latter: in recent years, low inflation rates have proved remarkably resilient, even following round after round of quantitative easing. Three trends explain why. First, technological innovation has driven down consumer prices and globalization has kept wages from rising. Second, the recurring financial panics of the past few decades have encouraged many lower-income economies to increase savings -- in the form of currency reserves -- as a form of insurance. That means they have been spending far less than they could, starving their economies of investments in such areas as infrastructure and defense, which would provide employment and drive up prices. Finally, throughout the developed world, increased life expectancies have led some private citizens to focus on saving for the longer term (think Japan). As a result, middle-aged adults and the elderly have started spending less on goods and services. These structural roots of today’s low inflation will only strengthen in the coming years, as global competition intensifies, fears of financial crises persist, and populations in Europe and the United States continue to age. If anything, policymakers should be more worried about deflation, which is already troubling the eurozone.

There is no need, then, for central banks to abandon their traditional focus on keeping demand high and inflation on target. Cash transfers stand a better chance of achieving those goals than do interest-rate shifts and quantitative easing, and at a much lower cost. Because they are more efficient, helicopter drops would require the banks to print much less money. By depositing the funds directly into millions of individual accounts -- spurring spending immediately -- central bankers wouldn’t need to print quantities of money equivalent to 20 percent of GDP.

The transfers’ overall impact would depend on their so-called fiscal multiplier, which measures how much GDP would rise for every $100 transferred. In the United States, the tax rebates provided by the Economic Stimulus Act of 2008, which amounted to roughly one percent of GDP, can serve as a useful guide: they are estimated to have had a multiplier of around 1.3. That means that an infusion of cash equivalent to two percent of GDP would likely grow the economy by about 2.6 percent. Transfers on that scale -- less than five percent of GDP -- would probably suffice to generate economic growth.

LET THEM HAVE CASH

Using cash transfers, central banks could boost spending without assuming the risks of keeping interest rates low. But transfers would only marginally address growing income inequality, another major threat to economic growth over the long term. In the past three decades, the wages of the bottom 40 percent of earners in developed countries have stagnated, while the very top earners have seen their incomes soar. The Bank of England estimates that the richest five percent of British households now own 40 percent of the total wealth of the United Kingdom -- a phenomenon now common across the developed world.

To reduce the gap between rich and poor, the French economist Thomas Piketty and others have proposed a global tax on wealth. But such a policy would be impractical. For one thing, the wealthy would probably use their political influence and financial resources to oppose the tax or avoid paying it. Around $29 trillion in offshore assets already lies beyond the reach of state treasuries, and the new tax would only add to that pile. In addition, the majority of the people who would likely have to pay -- the top ten percent of earners -- are not all that rich. Typically, the majority of households in the highest income tax brackets are upper-middle class, not superwealthy. Further burdening this group would be a hard sell politically and, as France’s recent budget problems demonstrate, would yield little financial benefit. Finally, taxes on capital would discourage private investment and innovation.

There is another way: instead of trying to drag down the top, governments could boost the bottom. Central banks could issue debt and use the proceeds to invest in a global equity index, a bundle of diverse investments with a value that rises and falls with the market, which they could hold in sovereign wealth funds. The Bank of England, the European Central Bank, and the Federal Reserve already own assets in excess of 20 percent of their countries’ GDPs, so there is no reason why they could not invest those assets in global equities on behalf of their citizens. After around 15 years, the funds could distribute their equity holdings to the lowest-earning 80 percent of taxpayers. The payments could be made to tax-exempt individual savings accounts, and governments could place simple constraints on how the capital could be used.

For example, beneficiaries could be required to retain the funds as savings or to use them to finance their education, pay off debts, start a business, or invest in a home. Such restrictions would encourage the recipients to think of the transfers as investments in the future rather than as lottery winnings. The goal, moreover, would be to increase wealth at the bottom end of the income distribution over the long run, which would do much to lower inequality.

Best of all, the system would be self-financing. Most governments can now issue debt at a real interest rate of close to zero. If they raised capital that way or liquidated the assets they currently possess, they could enjoy a five percent real rate of return -- a conservative estimate, given historical returns and current valuations. Thanks to the effect of compound interest, the profits from these funds could amount to around a 100 percent capital gain after just 15 years. Say a government issued debt equivalent to 20 percent of GDP at a real interest rate of zero and then invested the capital in an index of global equities. After 15 years, it could repay the debt generated and also transfer the excess capital to households. This is not alchemy. It’s a policy that would make the so-called equity risk premium -- the excess return that investors receive in exchange for putting their capital at risk -- work for everyone.

MO' MONEY, FEWER PROBLEMS

As things currently stand, the prevailing monetary policies have gone almost completely unchallenged, with the exception of proposals by Keynesian economists such as Lawrence Summers and Paul Krugman, who have called for government-financed spending on infrastructure and research. Such investments, the reasoning goes, would create jobs while making the United States more competitive. And now seems like the perfect time to raise the funds to pay for such work: governments can borrow for ten years at real interest rates of close to zero.

The problem with these proposals is that infrastructure spending takes too long to revive an ailing economy. In the United Kingdom, for example, policymakers have taken years to reach an agreement on building the high-speed rail project known as HS2 and an equally long time to settle on a plan to add a third runway at London’s Heathrow Airport. Such large, long-term investments are needed. But they shouldn’t be rushed. Just ask Berliners about the unnecessary new airport that the German government is building for over $5 billion, and which is now some five years behind schedule. Governments should thus continue to invest in infrastructure and research, but when facing insufficient demand, they should tackle the spending problem quickly and directly.

If cash transfers represent such a sure thing, then why has no one tried them? The answer, in part, comes down to an accident of history: central banks were not designed to manage spending. The first central banks, many of which were founded in the late nineteenth century, were designed to carry out a few basic functions: issue currency, provide liquidity to the government bond market, and mitigate banking panics. They mainly engaged in so-called open-market operations -- essentially, the purchase and sale of government bonds -- which provided banks with liquidity and determined the rate of interest in money markets. Quantitative easing, the latest variant of that bond-buying function, proved capable of stabilizing money markets in 2009, but at too high a cost considering what little growth it achieved.

A second factor explaining the persistence of the old way of doing business involves central banks’ balance sheets. Conventional accounting treats money -- bank notes and reserves -- as a liability. So if one of these banks were to issue cash transfers in excess of its assets, it could technically have a negative net worth. Yet it makes no sense to worry about the solvency of central banks: after all, they can always print more money.

The most powerful sources of resistance to cash transfers are political and ideological. In the United States, for example, the Fed is extremely resistant to legislative changes affecting monetary policy for fear of congressional actions that would limit its freedom of action in a future crisis (such as preventing it from bailing out foreign banks). Moreover, many American conservatives consider cash transfers to be socialist handouts. In Europe, which one might think would provide more fertile ground for such transfers, the German fear of inflation that led the European Central Bank to hike rates in 2011, in the middle of the greatest recession since the 1930s, suggests that ideological resistance can be found there, too.

Those who don’t like the idea of cash giveaways, however, should imagine that poor households received an unanticipated inheritance or tax rebate. An inheritance is a wealth transfer that has not been earned by the recipient, and its timing and amount lie outside the beneficiary’s control. Although the gift may come from a family member, in financial terms, it’s the same as a direct money transfer from the government. Poor people, of course, rarely have rich relatives and so rarely get inheritances -- but under the plan being proposed here, they would, every time it looked as though their country was at risk of entering a recession.

Unless one subscribes to the view that recessions are either therapeutic or deserved, there is no reason governments should not try to end them if they can, and cash transfers are a uniquely effective way of doing so. For one thing, they would quickly increase spending, and central banks could implement them instantaneously, unlike infrastructure spending or changes to the tax code, which typically require legislation. And in contrast to interest-rate cuts, cash transfers would affect demand directly, without the side effects of distorting financial markets and asset prices. They would also would help address inequality -- without skinning the rich.

Ideology aside, the main barriers to implementing this policy are surmountable. And the time is long past for this kind of innovation. Central banks are now trying to run twenty-first-century economies with a set of policy tools invented over a century ago. By relying too heavily on those tactics, they have ended up embracing policies with perverse consequences and poor payoffs. All it will take to change course is the courage, brains, and leadership to try something new.

As Bernanke made clear, the concept was not new: in the 1930s, the British economist John Maynard Keynes proposed burying bottles of bank notes in old coal mines; once unearthed (like gold), the cash would create new wealth and spur spending. The conservative economist Milton Friedman also saw the appeal of direct money transfers, which he likened to dropping cash out of a helicopter. Japan never tried using them, however, and the country’s economy has never fully recovered. Between 1993 and 2003, Japan’s annual growth rates averaged less than one percent.

Today, most economists agree that like Japan in the late 1990s, the global economy is suffering from insufficient spending, a problem that stems from a larger failure of governance. Central banks, including the U.S. Federal Reserve, have taken aggressive action, consistently lowering interest rates such that today they hover near zero. They have also pumped trillions of dollars’ worth of new money into the financial system. Yet such policies have only fed a damaging cycle of booms and busts, warping incentives and distorting asset prices, and now economic growth is stagnating while inequality gets worse. It’s well past time, then, for U.S. policymakers -- as well as their counterparts in other developed countries -- to consider a version of Friedman’s helicopter drops. In the short term, such cash transfers could jump-start the economy. Over the long term, they could reduce dependence on the banking system for growth and reverse the trend of rising inequality. The transfers wouldn’t cause damaging inflation, and few doubt that they would work. The only real question is why no government has tried them.

Instead of trying to drag down the top, governments should boost the bottom.

EASY MONEY

In theory, governments can boost spending in two ways: through fiscal policies (such as lowering taxes or increasing government spending) or through monetary policies (such as reducing interest rates or increasing the money supply). But over the past few decades, policymakers in many countries have come to rely almost exclusively on the latter. The shift has occurred for a number of reasons. Particularly in the United States, partisan divides over fiscal policy have grown too wide to bridge, as the left and the right have waged bitter fights over whether to increase government spending or cut tax rates. More generally, tax rebates and stimulus packages tend to face greater political hurdles than monetary policy shifts. Presidents and prime ministers need approval from their legislatures to pass a budget; that takes time, and the resulting tax breaks and government investments often benefit powerful constituencies rather than the economy as a whole. Many central banks, by contrast, are politically independent and can cut interest rates with a single conference call. Moreover, there is simply no real consensus about how to use taxes or spending to efficiently stimulate the economy.

Steady growth from the late 1980s to the early years of this century seemed to vindicate this emphasis on monetary policy. The approach presented major drawbacks, however. Unlike fiscal policy, which directly affects spending, monetary policy operates in an indirect fashion. Low interest rates reduce the cost of borrowing and drive up the prices of stocks, bonds, and homes. But stimulating the economy in this way is expensive and inefficient, and can create dangerous bubbles -- in real estate, for example -- and encourage companies and households to take on dangerous levels of debt.

That is precisely what happened during Alan Greenspan’s tenure as Fed chair, from 1997 to 2006: Washington relied too heavily on monetary policy to increase spending. Commentators often blame Greenspan for sowing the seeds of the 2008 financial crisis by keeping interest rates too low during the early years of this century. But Greenspan’s approach was merely a reaction to Congress’ unwillingness to use its fiscal tools. Moreover, Greenspan was completely honest about what he was doing. In testimony to Congress in 2002, he explained how Fed policy was affecting ordinary Americans:

"Particularly important in buoying spending [are] the very low levels of mortgage interest rates, which [encourage] households to purchase homes, refinance debt and lower debt service burdens, and extract equity from homes to finance expenditures. Fixed mortgage rates remain at historically low levels and thus should continue to fuel reasonably strong housing demand and, through equity extraction, to support consumer spending as well.

"Of course, Greenspan’s model crashed and burned spectacularly when the housing market imploded in 2008. Yet nothing has really changed since then. The United States merely patched its financial sector back together and resumed the same policies that created 30 years of financial bubbles. Consider what Bernanke, who came out of the academy to serve as Greenspan’s successor, did with his policy of “quantitative easing,” through which the Fed increased the money supply by purchasing billions of dollars’ worth of mortgage-backed securities and government bonds. Bernanke aimed to boost stock and bond prices in the same way that Greenspan had lifted home values. Their ends were ultimately the same: to increase consumer spending.

The overall effects of Bernanke’s policies have also been similar to those of Greenspan’s. Higher asset prices have encouraged a modest recovery in spending, but at great risk to the financial system and at a huge cost to taxpayers. Yet other governments have still followed Bernanke’s lead. Japan’s central bank, for example, has tried to use its own policy of quantitative easing to lift its stock market. So far, however, Tokyo’s efforts have failed to counteract the country’s chronic underconsumption. In the eurozone, the European Central Bank has attempted to increase incentives for spending by making its interest rates negative, charging commercial banks 0.1 percent to deposit cash. But there is little evidence that this policy has increased spending.

China is already struggling to cope with the consequences of similar policies, which it adopted in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. To keep the country’s economy afloat, Beijing aggressively cut interest rates and gave banks the green light to hand out an unprecedented number of loans. The results were a dramatic rise in asset prices and substantial new borrowing by individuals and financial firms, which led to dangerous instability. Chinese policymakers are now trying to sustain overall spending while reducing debt and making prices more stable. Like other governments, Beijing seems short on ideas about just how to do this. It doesn’t want to keep loosening monetary policy. But it hasn’t yet found a different way forward.

The broader global economy, meanwhile, may have already entered a bond bubble and could soon witness a stock bubble. Housing markets around the world, from Tel Aviv to Toronto, have overheated. Many in the private sector don’t want to take out any more loans; they believe their debt levels are already too high. That’s especially bad news for central bankers: when households and businesses refuse to rapidly increase their borrowing, monetary policy can’t do much to increase their spending. Over the past 15 years, the world’s major central banks have expanded their balance sheets by around $6 trillion, primarily through quantitative easing and other so-called liquidity operations. Yet in much of the developed world, inflation has barely budged.

To some extent, low inflation reflects intense competition in an increasingly globalized economy. But it also occurs when people and businesses are too hesitant to spend their money, which keeps unemployment high and wage growth low. In the eurozone, inflation has recently dropped perilously close to zero. And some countries, such as Portugal and Spain, may already be experiencing deflation. At best, the current policies are not working; at worst, they will lead to further instability and prolonged stagnation.

MAKE IT RAIN

Governments must do better. Rather than trying to spur private-sector spending through asset purchases or interest-rate changes, central banks, such as the Fed, should hand consumers cash directly. In practice, this policy could take the form of giving central banks the ability to hand their countries’ tax-paying households a certain amount of money. The government could distribute cash equally to all households or, even better, aim for the bottom 80 percent of households in terms of income. Targeting those who earn the least would have two primary benefits. For one thing, lower-income households are more prone to consume, so they would provide a greater boost to spending. For another, the policy would offset rising income inequality.

Such an approach would represent the first significant innovation in monetary policy since the inception of central banking, yet it would not be a radical departure from the status quo. Most citizens already trust their central banks to manipulate interest rates. And rate changes are just as redistributive as cash transfers. When interest rates go down, for example, those borrowing at adjustable rates end up benefiting, whereas those who save -- and thus depend more on interest income -- lose out.

Most economists agree that cash transfers from a central bank would stimulate demand. But policymakers nonetheless continue to resist the notion. In a 2012 speech, Mervyn King, then governor of the Bank of England, argued that transfers technically counted as fiscal policy, which falls outside the purview of central bankers, a view that his Japanese counterpart, Haruhiko Kuroda, echoed this past March. Such arguments, however, are merely semantic. Distinctions between monetary and fiscal policies are a function of what governments ask their central banks to do. In other words, cash transfers would become a tool of monetary policy as soon as the banks began using them.

Other critics warn that such helicopter drops could cause inflation. The transfers, however, would be a flexible tool. Central bankers could ramp them up whenever they saw fit and raise interest rates to offset any inflationary effects, although they probably wouldn’t have to do the latter: in recent years, low inflation rates have proved remarkably resilient, even following round after round of quantitative easing. Three trends explain why. First, technological innovation has driven down consumer prices and globalization has kept wages from rising. Second, the recurring financial panics of the past few decades have encouraged many lower-income economies to increase savings -- in the form of currency reserves -- as a form of insurance. That means they have been spending far less than they could, starving their economies of investments in such areas as infrastructure and defense, which would provide employment and drive up prices. Finally, throughout the developed world, increased life expectancies have led some private citizens to focus on saving for the longer term (think Japan). As a result, middle-aged adults and the elderly have started spending less on goods and services. These structural roots of today’s low inflation will only strengthen in the coming years, as global competition intensifies, fears of financial crises persist, and populations in Europe and the United States continue to age. If anything, policymakers should be more worried about deflation, which is already troubling the eurozone.

There is no need, then, for central banks to abandon their traditional focus on keeping demand high and inflation on target. Cash transfers stand a better chance of achieving those goals than do interest-rate shifts and quantitative easing, and at a much lower cost. Because they are more efficient, helicopter drops would require the banks to print much less money. By depositing the funds directly into millions of individual accounts -- spurring spending immediately -- central bankers wouldn’t need to print quantities of money equivalent to 20 percent of GDP.

The transfers’ overall impact would depend on their so-called fiscal multiplier, which measures how much GDP would rise for every $100 transferred. In the United States, the tax rebates provided by the Economic Stimulus Act of 2008, which amounted to roughly one percent of GDP, can serve as a useful guide: they are estimated to have had a multiplier of around 1.3. That means that an infusion of cash equivalent to two percent of GDP would likely grow the economy by about 2.6 percent. Transfers on that scale -- less than five percent of GDP -- would probably suffice to generate economic growth.

LET THEM HAVE CASH

Using cash transfers, central banks could boost spending without assuming the risks of keeping interest rates low. But transfers would only marginally address growing income inequality, another major threat to economic growth over the long term. In the past three decades, the wages of the bottom 40 percent of earners in developed countries have stagnated, while the very top earners have seen their incomes soar. The Bank of England estimates that the richest five percent of British households now own 40 percent of the total wealth of the United Kingdom -- a phenomenon now common across the developed world.

To reduce the gap between rich and poor, the French economist Thomas Piketty and others have proposed a global tax on wealth. But such a policy would be impractical. For one thing, the wealthy would probably use their political influence and financial resources to oppose the tax or avoid paying it. Around $29 trillion in offshore assets already lies beyond the reach of state treasuries, and the new tax would only add to that pile. In addition, the majority of the people who would likely have to pay -- the top ten percent of earners -- are not all that rich. Typically, the majority of households in the highest income tax brackets are upper-middle class, not superwealthy. Further burdening this group would be a hard sell politically and, as France’s recent budget problems demonstrate, would yield little financial benefit. Finally, taxes on capital would discourage private investment and innovation.

There is another way: instead of trying to drag down the top, governments could boost the bottom. Central banks could issue debt and use the proceeds to invest in a global equity index, a bundle of diverse investments with a value that rises and falls with the market, which they could hold in sovereign wealth funds. The Bank of England, the European Central Bank, and the Federal Reserve already own assets in excess of 20 percent of their countries’ GDPs, so there is no reason why they could not invest those assets in global equities on behalf of their citizens. After around 15 years, the funds could distribute their equity holdings to the lowest-earning 80 percent of taxpayers. The payments could be made to tax-exempt individual savings accounts, and governments could place simple constraints on how the capital could be used.

For example, beneficiaries could be required to retain the funds as savings or to use them to finance their education, pay off debts, start a business, or invest in a home. Such restrictions would encourage the recipients to think of the transfers as investments in the future rather than as lottery winnings. The goal, moreover, would be to increase wealth at the bottom end of the income distribution over the long run, which would do much to lower inequality.

Best of all, the system would be self-financing. Most governments can now issue debt at a real interest rate of close to zero. If they raised capital that way or liquidated the assets they currently possess, they could enjoy a five percent real rate of return -- a conservative estimate, given historical returns and current valuations. Thanks to the effect of compound interest, the profits from these funds could amount to around a 100 percent capital gain after just 15 years. Say a government issued debt equivalent to 20 percent of GDP at a real interest rate of zero and then invested the capital in an index of global equities. After 15 years, it could repay the debt generated and also transfer the excess capital to households. This is not alchemy. It’s a policy that would make the so-called equity risk premium -- the excess return that investors receive in exchange for putting their capital at risk -- work for everyone.

MO' MONEY, FEWER PROBLEMS

As things currently stand, the prevailing monetary policies have gone almost completely unchallenged, with the exception of proposals by Keynesian economists such as Lawrence Summers and Paul Krugman, who have called for government-financed spending on infrastructure and research. Such investments, the reasoning goes, would create jobs while making the United States more competitive. And now seems like the perfect time to raise the funds to pay for such work: governments can borrow for ten years at real interest rates of close to zero.

The problem with these proposals is that infrastructure spending takes too long to revive an ailing economy. In the United Kingdom, for example, policymakers have taken years to reach an agreement on building the high-speed rail project known as HS2 and an equally long time to settle on a plan to add a third runway at London’s Heathrow Airport. Such large, long-term investments are needed. But they shouldn’t be rushed. Just ask Berliners about the unnecessary new airport that the German government is building for over $5 billion, and which is now some five years behind schedule. Governments should thus continue to invest in infrastructure and research, but when facing insufficient demand, they should tackle the spending problem quickly and directly.

If cash transfers represent such a sure thing, then why has no one tried them? The answer, in part, comes down to an accident of history: central banks were not designed to manage spending. The first central banks, many of which were founded in the late nineteenth century, were designed to carry out a few basic functions: issue currency, provide liquidity to the government bond market, and mitigate banking panics. They mainly engaged in so-called open-market operations -- essentially, the purchase and sale of government bonds -- which provided banks with liquidity and determined the rate of interest in money markets. Quantitative easing, the latest variant of that bond-buying function, proved capable of stabilizing money markets in 2009, but at too high a cost considering what little growth it achieved.

A second factor explaining the persistence of the old way of doing business involves central banks’ balance sheets. Conventional accounting treats money -- bank notes and reserves -- as a liability. So if one of these banks were to issue cash transfers in excess of its assets, it could technically have a negative net worth. Yet it makes no sense to worry about the solvency of central banks: after all, they can always print more money.

The most powerful sources of resistance to cash transfers are political and ideological. In the United States, for example, the Fed is extremely resistant to legislative changes affecting monetary policy for fear of congressional actions that would limit its freedom of action in a future crisis (such as preventing it from bailing out foreign banks). Moreover, many American conservatives consider cash transfers to be socialist handouts. In Europe, which one might think would provide more fertile ground for such transfers, the German fear of inflation that led the European Central Bank to hike rates in 2011, in the middle of the greatest recession since the 1930s, suggests that ideological resistance can be found there, too.

Those who don’t like the idea of cash giveaways, however, should imagine that poor households received an unanticipated inheritance or tax rebate. An inheritance is a wealth transfer that has not been earned by the recipient, and its timing and amount lie outside the beneficiary’s control. Although the gift may come from a family member, in financial terms, it’s the same as a direct money transfer from the government. Poor people, of course, rarely have rich relatives and so rarely get inheritances -- but under the plan being proposed here, they would, every time it looked as though their country was at risk of entering a recession.

Unless one subscribes to the view that recessions are either therapeutic or deserved, there is no reason governments should not try to end them if they can, and cash transfers are a uniquely effective way of doing so. For one thing, they would quickly increase spending, and central banks could implement them instantaneously, unlike infrastructure spending or changes to the tax code, which typically require legislation. And in contrast to interest-rate cuts, cash transfers would affect demand directly, without the side effects of distorting financial markets and asset prices. They would also would help address inequality -- without skinning the rich.

Ideology aside, the main barriers to implementing this policy are surmountable. And the time is long past for this kind of innovation. Central banks are now trying to run twenty-first-century economies with a set of policy tools invented over a century ago. By relying too heavily on those tactics, they have ended up embracing policies with perverse consequences and poor payoffs. All it will take to change course is the courage, brains, and leadership to try something new.

Comment