After paying my bills the other day I had home heating and electric utility costs on my mind—the winter having been an unusually harsh one in NYC like much of the rest of the nation. But then I noticed a story by an outfit called CNS News.com that contained some great historical graphs on decades worth of utility prices, and I was duly reminded that this wintery winter wasn’t all that: Home utility and fuel costs have been rising at a pretty robust clip for more than a decade now.

Indeed, notwithstanding the modest weight (5%) ascribed to utilities and fuel in the BLS price basket, there are few households in America that have escaped their relentless grind higher. Nor would most everyday Americans shuck this off as a trivial component of their own cost-of-living index or express relief that all remains copasetic on the inflation front— since these large utility and fuel gains have been offset by falling iPad prices and hedonic adjustments to the price of their $40,000 family sedan.

The fact is, the price index for electrical power increased by 5.3% during the past 12 months and has reached an all-time high. But I get it. That doesn’t count as “inflation” because its not in the Fed’s preferred measuring stick—the PCE deflator ex-food and energy. And, yes, they do have a point about the short-run volatility of commodity-driven components of the index like the price of Kwh’s from your local utility.

Heck, the price of power is even seasonal—-rising in the spring, peaking with the summer air-con load and then re-tracing in fall-winter. The latter is supposedly already factored into the BLS’ seasonal maladjustments. But, still, it can be granted that on a short-run basis of a few quarters or even years there is probably a lot of off-trend “noise” in electricity prices.

When it gets to a time frame of a decade running, however, I’ll put my foot down. Back in 2004-05, the government said the average price for electrical power was 9.0 cents/ Kwh compared to the 13.5 cents posted last week for March. Doing the math, that’s a compound growth rate of 4.5% over a decade. And that’s not noise. Its signal. Its inflation.

In its article on the surging trend in utility bills, CNSNews.com actually cited the whole index numbers for March and prior year, not just the monthly delta. It then added insult to bubble news injury by placing the utility power gain in the context of overall energy prices trends:

The BLS’s seasonally adjusted electricity price index rose to 209.341 this March, the highest it has ever been, up 10.537 points or 5.3 percent–from 198.804 in March 2013…..Over the last 12 months, the energy index has increased 0.4 percent, with the natural gas index rising 16.4 percent, the electricity index increasing 5.3 percent, and the fuel oil index advancing 2.1 percent. These increases more than offset a 4.7 percent decline in the gasoline index.”

So the above paragraph begs some questions. For one thing, given the magnitude of the index number change for electricity and the double digit year/year change for natural gas something other than falling iPad prices comes to mind. Yet the financial press has so dumbed-down the economic data release narrative via near exclusive focus on algo-feeding monthly “deltas” that our monetary politburo can get away with ludicrous memes like “low-flation”. The trends which refute this nonsense are actually there in plain sight in the data—but are rarely encountered by even the attentive public.

So herein an essay on the overwhelming evidence of inflation during the decade long era in which the central bankers have been braying about “deflation”. Herein, too, some startling evidence of the complicity of the government statistical mills in using the inflation that is not seen (i.e. “imputed”) to dilute and obscure the inflation that is seen (i.e. utility bills).

To be sure, the above paragraph from CNS News might be read to mean that on a 12-month basis inflation is well-contained—even in the energy world. While electrical power and natural gas prices have been roaring upward, weakness in crude oil based products—fuel oil and gasoline—have off-set nearly all the rise. So possibly nothing to see here. Just more “noise” in the index to be left to the experts in the Eccles Building.

Not exactly. Some deep historical perspective is always a good place to start. Otherwise you get caught up in the Fed’s futile mind game of trying to assess the vast outpouring of short-term noise and signal emanating from a $17 trillion post-industrial economy. Indeed, such “in-coming” data is so riddled with guesstimates, imputations, faulty seasonal maladjustments and subsequent revisions as to be nearly meaningless.

And the proof of that is in the transcripts of Fed meetings themselves—released as they are with a 5-year lag. The transcripts show that especially at turning points in the economic and financial cycle, the monetary politburo is essentially clueless—- as it was in much of the spring, summer and early fall of 2008. More importantly, the “in-coming” data cited with grave authority by many FOMC participants with respect to GDP components, jobs, inflation and other macroeconomic trends is often nowhere to be found in the current official data—it having been revised away in the interim.

So starting off with a 100-year perspective on electrical power prices, the chart below makes the big picture point that the rise of Keynesian central banking after August 1971 has been associated with persistent inflation, not deflation. Thus, between 1913 and the early 1960s, electrical power prices in the US were flat—there was no trend inflation whatsoever.

Not coincidently, that era ended with the Johnson-Nixon assault on fiscal rectitude and sound money after 1965. Indeed, ever since the official arrival of discretionary central banking in 1971—that is, floating money anchored to the whims of only the FOMC— there has been a systematic inflationary bias in utility prices as is self-evident below.

But there’s more. June 1997 can well be pinpointed as the date at which the Greenspan Fed went all-in for its modern policy of endless financial market accommodation as its primary policy tool. At that juncture the Fed had spent a few months contemplating Greenspan’s famous “irrational exuberance” warning of December 1996 and had actually made a half-hearted attempt to slow Wall Street’s thundering herd by nudging up interest rates in April. After a decidedly negative reaction, however, rates were eased in June 1997, and the Eccles Building has never looked back.

During the subsequent 17 years the Fed’s balance sheet has exploded from $400 billion to what will soon be $4.5 trillion. Call it 10X. For perspective, compare it to money GDP of 2X over the same period.

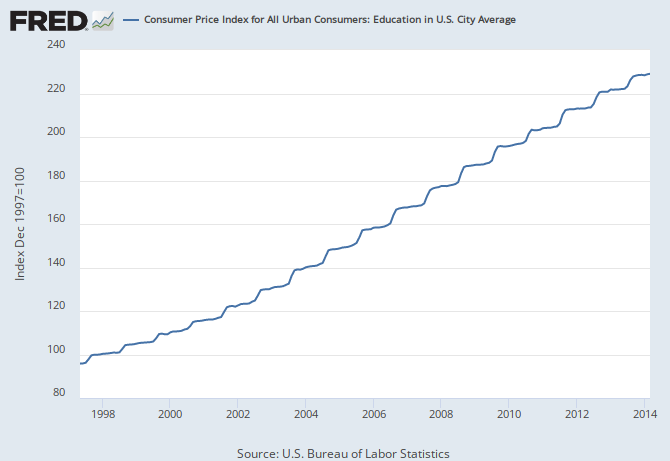

More importantly, recall that during most of this period the Fed has conducted recurrent jousts against threated, looming or just imagined “deflation”. Yet as the graph below shows, the average CPI gain over the period was 2.3%/year; and, appropriately, nothing is “ex’d” out of that number because every single American citizen did eat and need heating and transportation fuel during that 17-year time frame.

But here’s the bigger point. With respect to that part of inflation which is “seen”, as in a monthly utility bill, the rate of increase was much higher at 3.5% per annum. For those who think this kind of “moderate” inflation is a salutary thing, consider what a dollar saved today would be worth after a thirty year working life time under that 3.5% inflation regime. Answer: 35 cents.

In short, not a single one of America’s 115 million households—renters, owners and borrowers alike—escape the monthly electric utility bill. At $200 per month its not trivial, and the 3.5% trend of the past 17 years has just accelerated to 5.3%. And that happened straight into the jaws of what is being heralded as “low-flation”.

The above flat-out inflationary trend of nearly two decades running is by no means unique to electrical power prices. Consider gasoline, which has ticked down slightly during recent quarters, but about which there is no doubt regarding the trend.

Over the past seventeen years, retail gasoline prices are up at a 6.5% CAGR and by an almost equally inflationary 6.0% over the past nine years. Even giving allowance to the skyrocketing global petroleum prices after September 2007 and their subsequent crash after crude peaked at $150/bbl. a year later, gasoline prices have been heading upwards at a 3.0% rate since the eve of the financial crisis.

So let the recent downward squiggles depicted in the chart below not trouble the monetary politburo. People who travel by internal combustion machine have experienced a steady wallop of inflation for a long as the Fed’s fireman have been professing to be warding off deflation.

OK, there were some people around the Princeton campus who didn’t own a car and ambulated by bike or on foot. But they did need heating fuel in the winter and there was nothing disinflationary about meeting that expense—especially for the 10 million households who heat with home heating oil.

During the last 17-years the index has climbed at a 11% annual rate; and by a 6% CAGR since 2007. The fact that we are not at the momentary oil-price blow-off peak of mid-2008 is truly a case of “cold comfort”. An essential commodity that cost about $0.50 per gallon when Bernanke first started gumming about the “deflation” danger in 2002 now costs $3.00.

Yes, over reasonably long periods of time, most people eat and drink, too. Self-evidently, there is nothing deflationary, disinflationary or otherwise benign about the BLS sub-index for food and beverages. It is up by 2.4% annually during the 17-years since Greenspan kicked monetary discipline out of the Eccles building; and by 2.0% per year since Bernanke launched his own war against deflation in late 2007.

Moreover, there is nothing in that relentlessly ascending curve that speaks of a sudden downshift in recent quarters. During the 12 quarters ending in March 2014, food and beverage prices rose at a 2.2% annual rate.

The above observation leads to an obvious corollary. If you heat it, you have to rent it or own it. For the 40 million households who rent their castle, there has obviously been nothing very deflationary for a long time. For the past 17-years, rents have risen a 3.0% compound rate. And there is no sign of meaningful deceleration there, either. Rents were up by 2.8% in the year ending in March, and by 2.7% in the year before that.

There remains the 75 million households who own their homes, and according to the BLS, the rate of inflation there has been considerably more benign. We will take that apart forthwith, but it is worth noting that whether households own or rent, they end up with costs for water and sewer, trash collection and repairs.

According to the BLS, there has been no signs of deflation in any of these expense categories, either. The cost of water and sewer and trash collection, for example, has doubled since Greenspan had his irrational exuberance moment. That amounts to an 4.5 % rate of annual increase in every day life. As for home repairs, the CAGR is up by 4.8% per year since 1997. And in none of these categories there been any significant deceleration during recent periods.

So that gets us to the proverbial owners equivalent rent(OER)—about which three things are notable. First, it counts for 25% of the regular CPI. Secondly, it comprises 40% of that unique specie of inflation visible in the Eccles building—that is to say, the CPI less things which are inflating such as food and energy. And finally, it is derived by a methodology that can only be described as a preposterous bureaucratic farce.

Specifically, each month several thousand survey respondents, who own their homes and would likely not dream of renting their castle to strangers, and who are also not in the professional landlord business, are asked what they might expect to earn monthly if the did rent their home.

Self-evidently, they have no clue— and so neither does the Commerce Department which conducts the survery or the BLS which processes the data. And that assumes that the raw data did indeed data come from respondents, rather than consisting of numbers plugged in at the end of the month by Census Bureau employees rushing to finish their quota of interviews. There have been some recent news leaks to exactly that point.

Yet even as so dubiously measured, there has been significant OER inflation over the last 17 years: 2.4% annually to be exact. That figure has mysteriously slowed down to 1.7% annually since 2007, but even that rate of gain would not exactly qualify as deflation. OER would double every 40 years at that rate.

But here’s the thing. During the same 17-year period home prices as measured by the Case-Shiller repeat sales index have risen at a 5.2% annual rate—double the OER. And that’s notwithstanding the partial round trip of the housing sector boom and bust during that period.

Undoubtedly, some spreadsheet wiz at the Fed would say do not be troubled by this yawning gap between housing prices and OER. In its wisdom, the Fed has radically repressed the benchmark Treasury rate over this period, meaning that the “carry” cost of homeownership has declined sharply. So, yes, the fact that the housing asset price rose at 2X the rate of imputed rents over the past 17 years all makes sense!

Needless to say, now that interest rates are beginning to normalize the implication would be that the carry cost of ownership—that is, OER—-should begin to accelerate, too. Self-evidently, the deflation fighters in the Eccles building do not expect that—perhaps because they have a front row seat at the government fudge factory where OER is manufactured.

There is one component of the CPI that has experienced genuine deflation since the 1990s—and that is tradable goods subject to the withering force of labor cost reduction that resulted from draining the rice paddies of East Asia. Thus, the index for household furniture, appliances, furnishings, tools and supplies—which has a 4% weight in the CPI— has actually decline slightly since 1997.

The same is true of apparel and shoes which account for another 3.5% of the CPI. Still, household goods are down by only a cumulative 2% over the past 17 years and apparel and shoes by 4%. Those welcome but modest declines pale into insignificance relative to the 50-100% cumulative gains for the commodities and services highlighted above.

And the decline in tradable goods prices do not even begin to off-set the massive but partially invisible rise in the cost of medical, education and other services as will be outlined in Part 2.

Suffice it to say, the monetary politburo has well and truly reached a point of sheer desperation. To keep the Wall Street gamblers in play it needs to keep the money market rates at zero, and therefore the carry trades in business. But 7 years of ZIRP is so insensible on its face that it requires the invention of a giant, preposterous lie—-the myth of “low-flation”—to keep the printing presses humming in the basement of the Eccles Building.

Indeed, notwithstanding the modest weight (5%) ascribed to utilities and fuel in the BLS price basket, there are few households in America that have escaped their relentless grind higher. Nor would most everyday Americans shuck this off as a trivial component of their own cost-of-living index or express relief that all remains copasetic on the inflation front— since these large utility and fuel gains have been offset by falling iPad prices and hedonic adjustments to the price of their $40,000 family sedan.

The fact is, the price index for electrical power increased by 5.3% during the past 12 months and has reached an all-time high. But I get it. That doesn’t count as “inflation” because its not in the Fed’s preferred measuring stick—the PCE deflator ex-food and energy. And, yes, they do have a point about the short-run volatility of commodity-driven components of the index like the price of Kwh’s from your local utility.

Heck, the price of power is even seasonal—-rising in the spring, peaking with the summer air-con load and then re-tracing in fall-winter. The latter is supposedly already factored into the BLS’ seasonal maladjustments. But, still, it can be granted that on a short-run basis of a few quarters or even years there is probably a lot of off-trend “noise” in electricity prices.

When it gets to a time frame of a decade running, however, I’ll put my foot down. Back in 2004-05, the government said the average price for electrical power was 9.0 cents/ Kwh compared to the 13.5 cents posted last week for March. Doing the math, that’s a compound growth rate of 4.5% over a decade. And that’s not noise. Its signal. Its inflation.

In its article on the surging trend in utility bills, CNSNews.com actually cited the whole index numbers for March and prior year, not just the monthly delta. It then added insult to bubble news injury by placing the utility power gain in the context of overall energy prices trends:

The BLS’s seasonally adjusted electricity price index rose to 209.341 this March, the highest it has ever been, up 10.537 points or 5.3 percent–from 198.804 in March 2013…..Over the last 12 months, the energy index has increased 0.4 percent, with the natural gas index rising 16.4 percent, the electricity index increasing 5.3 percent, and the fuel oil index advancing 2.1 percent. These increases more than offset a 4.7 percent decline in the gasoline index.”

So the above paragraph begs some questions. For one thing, given the magnitude of the index number change for electricity and the double digit year/year change for natural gas something other than falling iPad prices comes to mind. Yet the financial press has so dumbed-down the economic data release narrative via near exclusive focus on algo-feeding monthly “deltas” that our monetary politburo can get away with ludicrous memes like “low-flation”. The trends which refute this nonsense are actually there in plain sight in the data—but are rarely encountered by even the attentive public.

So herein an essay on the overwhelming evidence of inflation during the decade long era in which the central bankers have been braying about “deflation”. Herein, too, some startling evidence of the complicity of the government statistical mills in using the inflation that is not seen (i.e. “imputed”) to dilute and obscure the inflation that is seen (i.e. utility bills).

To be sure, the above paragraph from CNS News might be read to mean that on a 12-month basis inflation is well-contained—even in the energy world. While electrical power and natural gas prices have been roaring upward, weakness in crude oil based products—fuel oil and gasoline—have off-set nearly all the rise. So possibly nothing to see here. Just more “noise” in the index to be left to the experts in the Eccles Building.

Not exactly. Some deep historical perspective is always a good place to start. Otherwise you get caught up in the Fed’s futile mind game of trying to assess the vast outpouring of short-term noise and signal emanating from a $17 trillion post-industrial economy. Indeed, such “in-coming” data is so riddled with guesstimates, imputations, faulty seasonal maladjustments and subsequent revisions as to be nearly meaningless.

And the proof of that is in the transcripts of Fed meetings themselves—released as they are with a 5-year lag. The transcripts show that especially at turning points in the economic and financial cycle, the monetary politburo is essentially clueless—- as it was in much of the spring, summer and early fall of 2008. More importantly, the “in-coming” data cited with grave authority by many FOMC participants with respect to GDP components, jobs, inflation and other macroeconomic trends is often nowhere to be found in the current official data—it having been revised away in the interim.

So starting off with a 100-year perspective on electrical power prices, the chart below makes the big picture point that the rise of Keynesian central banking after August 1971 has been associated with persistent inflation, not deflation. Thus, between 1913 and the early 1960s, electrical power prices in the US were flat—there was no trend inflation whatsoever.

Not coincidently, that era ended with the Johnson-Nixon assault on fiscal rectitude and sound money after 1965. Indeed, ever since the official arrival of discretionary central banking in 1971—that is, floating money anchored to the whims of only the FOMC— there has been a systematic inflationary bias in utility prices as is self-evident below.

But there’s more. June 1997 can well be pinpointed as the date at which the Greenspan Fed went all-in for its modern policy of endless financial market accommodation as its primary policy tool. At that juncture the Fed had spent a few months contemplating Greenspan’s famous “irrational exuberance” warning of December 1996 and had actually made a half-hearted attempt to slow Wall Street’s thundering herd by nudging up interest rates in April. After a decidedly negative reaction, however, rates were eased in June 1997, and the Eccles Building has never looked back.

During the subsequent 17 years the Fed’s balance sheet has exploded from $400 billion to what will soon be $4.5 trillion. Call it 10X. For perspective, compare it to money GDP of 2X over the same period.

More importantly, recall that during most of this period the Fed has conducted recurrent jousts against threated, looming or just imagined “deflation”. Yet as the graph below shows, the average CPI gain over the period was 2.3%/year; and, appropriately, nothing is “ex’d” out of that number because every single American citizen did eat and need heating and transportation fuel during that 17-year time frame.

But here’s the bigger point. With respect to that part of inflation which is “seen”, as in a monthly utility bill, the rate of increase was much higher at 3.5% per annum. For those who think this kind of “moderate” inflation is a salutary thing, consider what a dollar saved today would be worth after a thirty year working life time under that 3.5% inflation regime. Answer: 35 cents.

In short, not a single one of America’s 115 million households—renters, owners and borrowers alike—escape the monthly electric utility bill. At $200 per month its not trivial, and the 3.5% trend of the past 17 years has just accelerated to 5.3%. And that happened straight into the jaws of what is being heralded as “low-flation”.

The above flat-out inflationary trend of nearly two decades running is by no means unique to electrical power prices. Consider gasoline, which has ticked down slightly during recent quarters, but about which there is no doubt regarding the trend.

Over the past seventeen years, retail gasoline prices are up at a 6.5% CAGR and by an almost equally inflationary 6.0% over the past nine years. Even giving allowance to the skyrocketing global petroleum prices after September 2007 and their subsequent crash after crude peaked at $150/bbl. a year later, gasoline prices have been heading upwards at a 3.0% rate since the eve of the financial crisis.

So let the recent downward squiggles depicted in the chart below not trouble the monetary politburo. People who travel by internal combustion machine have experienced a steady wallop of inflation for a long as the Fed’s fireman have been professing to be warding off deflation.

OK, there were some people around the Princeton campus who didn’t own a car and ambulated by bike or on foot. But they did need heating fuel in the winter and there was nothing disinflationary about meeting that expense—especially for the 10 million households who heat with home heating oil.

During the last 17-years the index has climbed at a 11% annual rate; and by a 6% CAGR since 2007. The fact that we are not at the momentary oil-price blow-off peak of mid-2008 is truly a case of “cold comfort”. An essential commodity that cost about $0.50 per gallon when Bernanke first started gumming about the “deflation” danger in 2002 now costs $3.00.

Yes, over reasonably long periods of time, most people eat and drink, too. Self-evidently, there is nothing deflationary, disinflationary or otherwise benign about the BLS sub-index for food and beverages. It is up by 2.4% annually during the 17-years since Greenspan kicked monetary discipline out of the Eccles building; and by 2.0% per year since Bernanke launched his own war against deflation in late 2007.

Moreover, there is nothing in that relentlessly ascending curve that speaks of a sudden downshift in recent quarters. During the 12 quarters ending in March 2014, food and beverage prices rose at a 2.2% annual rate.

The above observation leads to an obvious corollary. If you heat it, you have to rent it or own it. For the 40 million households who rent their castle, there has obviously been nothing very deflationary for a long time. For the past 17-years, rents have risen a 3.0% compound rate. And there is no sign of meaningful deceleration there, either. Rents were up by 2.8% in the year ending in March, and by 2.7% in the year before that.

There remains the 75 million households who own their homes, and according to the BLS, the rate of inflation there has been considerably more benign. We will take that apart forthwith, but it is worth noting that whether households own or rent, they end up with costs for water and sewer, trash collection and repairs.

According to the BLS, there has been no signs of deflation in any of these expense categories, either. The cost of water and sewer and trash collection, for example, has doubled since Greenspan had his irrational exuberance moment. That amounts to an 4.5 % rate of annual increase in every day life. As for home repairs, the CAGR is up by 4.8% per year since 1997. And in none of these categories there been any significant deceleration during recent periods.

So that gets us to the proverbial owners equivalent rent(OER)—about which three things are notable. First, it counts for 25% of the regular CPI. Secondly, it comprises 40% of that unique specie of inflation visible in the Eccles building—that is to say, the CPI less things which are inflating such as food and energy. And finally, it is derived by a methodology that can only be described as a preposterous bureaucratic farce.

Specifically, each month several thousand survey respondents, who own their homes and would likely not dream of renting their castle to strangers, and who are also not in the professional landlord business, are asked what they might expect to earn monthly if the did rent their home.

Self-evidently, they have no clue— and so neither does the Commerce Department which conducts the survery or the BLS which processes the data. And that assumes that the raw data did indeed data come from respondents, rather than consisting of numbers plugged in at the end of the month by Census Bureau employees rushing to finish their quota of interviews. There have been some recent news leaks to exactly that point.

Yet even as so dubiously measured, there has been significant OER inflation over the last 17 years: 2.4% annually to be exact. That figure has mysteriously slowed down to 1.7% annually since 2007, but even that rate of gain would not exactly qualify as deflation. OER would double every 40 years at that rate.

But here’s the thing. During the same 17-year period home prices as measured by the Case-Shiller repeat sales index have risen at a 5.2% annual rate—double the OER. And that’s notwithstanding the partial round trip of the housing sector boom and bust during that period.

Undoubtedly, some spreadsheet wiz at the Fed would say do not be troubled by this yawning gap between housing prices and OER. In its wisdom, the Fed has radically repressed the benchmark Treasury rate over this period, meaning that the “carry” cost of homeownership has declined sharply. So, yes, the fact that the housing asset price rose at 2X the rate of imputed rents over the past 17 years all makes sense!

Needless to say, now that interest rates are beginning to normalize the implication would be that the carry cost of ownership—that is, OER—-should begin to accelerate, too. Self-evidently, the deflation fighters in the Eccles building do not expect that—perhaps because they have a front row seat at the government fudge factory where OER is manufactured.

There is one component of the CPI that has experienced genuine deflation since the 1990s—and that is tradable goods subject to the withering force of labor cost reduction that resulted from draining the rice paddies of East Asia. Thus, the index for household furniture, appliances, furnishings, tools and supplies—which has a 4% weight in the CPI— has actually decline slightly since 1997.

The same is true of apparel and shoes which account for another 3.5% of the CPI. Still, household goods are down by only a cumulative 2% over the past 17 years and apparel and shoes by 4%. Those welcome but modest declines pale into insignificance relative to the 50-100% cumulative gains for the commodities and services highlighted above.

And the decline in tradable goods prices do not even begin to off-set the massive but partially invisible rise in the cost of medical, education and other services as will be outlined in Part 2.

Suffice it to say, the monetary politburo has well and truly reached a point of sheer desperation. To keep the Wall Street gamblers in play it needs to keep the money market rates at zero, and therefore the carry trades in business. But 7 years of ZIRP is so insensible on its face that it requires the invention of a giant, preposterous lie—-the myth of “low-flation”—to keep the printing presses humming in the basement of the Eccles Building.

Comment