OLYMPIA, Wash. — On Christmas Eve, Kevin Johnson received the following gifts: a bed and mattress, a blanket and sheets, a desk and chair, a toilet and sink, towels and washcloths, toothpaste and floss, and a brand-new house.

Mr. Johnson, a 48-year-old day laborer, did not find that last item beneath the Christmas tree, although it nearly would have fit. At 144 square feet — 8 by 18 feet, or roughly the dimensions of a Chevrolet Suburban — the rental house was small. Tiny would be a better descriptor. It was just half the size of the “micro” apartments that former Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg proposed for New York City.

This scale bothered Mr. Johnson not at all, and a few weeks after moving in, he listed a few favorite design features. “A roof,” he said. “Heat.” A flush toilet! The tents where he had lived for most of the last seven years hadn’t provided any of those things.

In what seemed like an Oprah stunt of old, Mr. Johnson’s friends (21 men and seven women) also moved into tiny houses on Dec. 24. They had all been members of a homeless community called Camp Quixote, a floating tent city that moved more than 20 times after its founding in 2007.

Beyond its recent good fortune, the settlement was — and is — exceptional. Quixote Village, as it is now called, practices self-governance, with elected leadership and membership rules. While a nonprofit board called Panza funds and guides the project, needing help is not the same thing as being helpless. As Mr. Johnson likes to say, “I’m homeless, not stupid.”

A planning committee, including Mr. Johnson, collaborated with Garner Miller, an architect, to create the new village’s site layout and living model. Later, the plans were presented to an all-camp assembly. “Those were some of the best-run and most efficient meetings I’ve ever been involved in,” said Mr. Miller, a partner at MSGS Architects. “I would do those over a school board any day.”

The residents lobbied for a horseshoe layout rather than clusters of cottages, in order to minimize cliques. And they traded interior area for sitting porches. The social space lies outside the cottage. Or as Mr. Johnson put it, “If I don’t want to see anybody, I don’t have to.”

It is rare that folks who live on the street have the chance to collaborate on a 2.1-acre, $3.05 million real estate development. Nearly as surprising is that Quixote Village may become a template for homeless housing projects across the country. The community has already hosted delegations from Santa Cruz, Calif.; Portland, Ore.; and Seattle; and fielded inquiries from homeless advocates in Ann Arbor, Mich.; Salt Lake City; and Prince George’s County, Md.

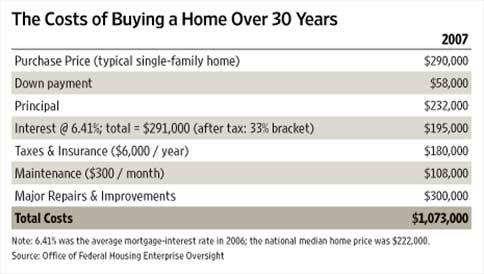

Some advantages to building small are obvious. Ginger Segel, of the nonprofit developer Community Frameworks, points to construction costs at Quixote Village of just $19,000 a unit (which included paying labor at the prevailing commercial wage). Showers, laundry and a shared kitchen have been concentrated in a community center. When you add in the cost of site preparation and the community building, the 30 finished units cost $88,000 each.

By comparison, Ms. Segel, 48, said, “I think the typical studio apartment for a homeless adult in western Washington costs between $200,000 and $250,000 to build.” In a sense, though, the difference is meaningless. Olympia and surrounding Thurston County hadn’t built any such housing for homeless adults since 2007.

Most of that demographic, an estimated 450 souls, is unemployed. While the residents of Quixote Village are expected to pay 30 percent of their income toward rent, 15 of the 29 individuals reported a sum of zero. Ms. Segel added that the average annual income for the rest of the residents — including wages, pensions and Social Security payments — is about $3,100 each.

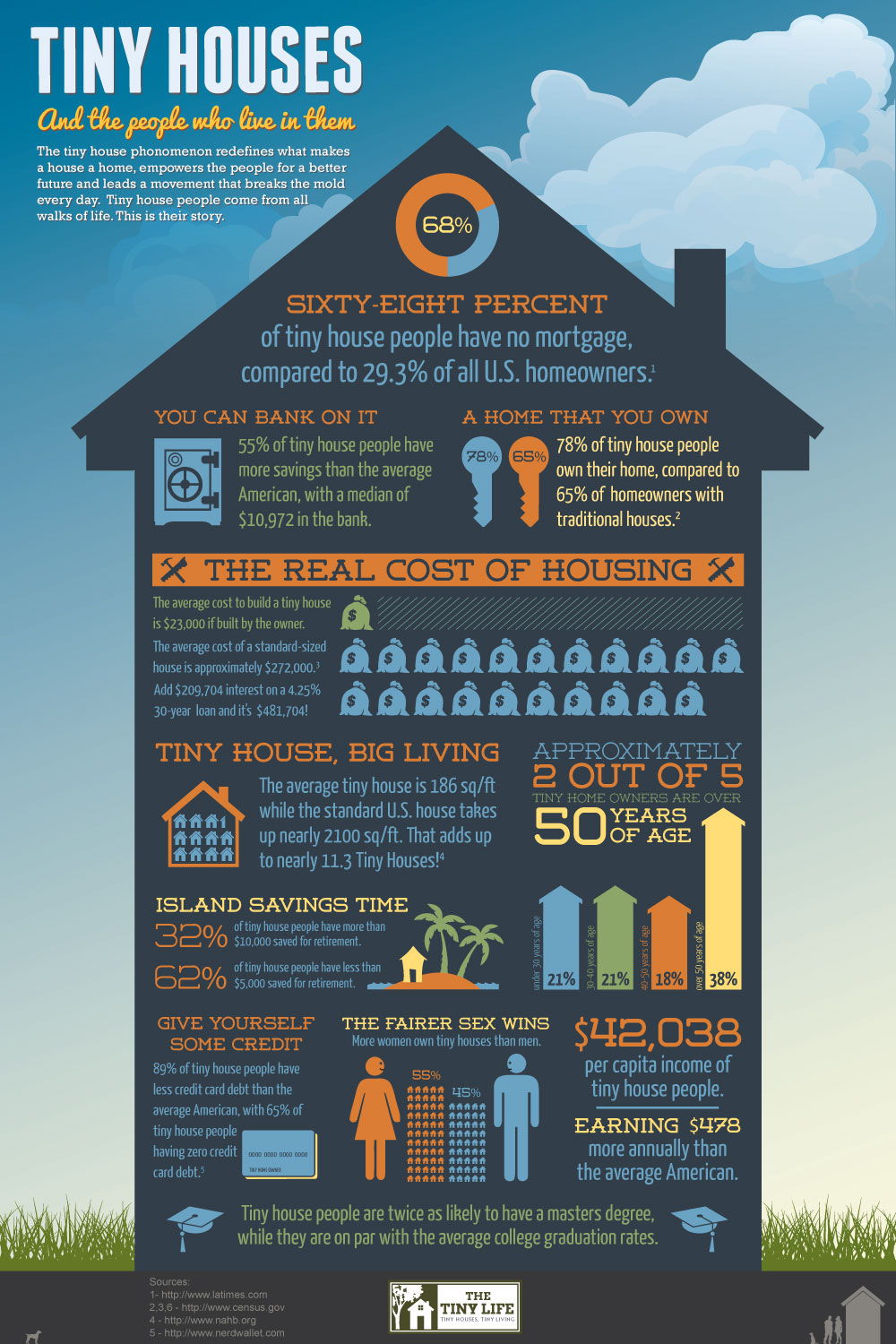

Regular affordable housing is a luxury these folks cannot afford. “This, to my knowledge, is the first example of using micro-housing as subsidized housing for very poor people,” Ms. Segel said. “It’s such an obvious thing. People are living in tents. They’re living in cars. They’re living in the woods.”

The “woods” is both an abstraction and a real place. See the fir trees behind Quixote Village, on the far side of the freight rail tracks? Last summer, Rebekah Johnson (no relation to Mr. Johnson) subsisted out there in a tent with her former boyfriend, just off a bike trail.

Comment