it's usually the coverup that proves fatal . . .

By MICHAEL BARBARO

He was, he said, heartbroken. Embarrassed. Sad. Disappointed. Humiliated.

By the end of an extraordinary and exhaustive 107-minute news conference, Chris Christie had transformed himself from a belligerent chief executive, famed for ridiculing his detractors, into a deeply wronged father figure, shaking his head, whispering his words and verging on tears.

The bravado had vanished. The certitude was gone.

In its place was an entirely new vocabulary of self-doubt and a once unthinkable spectacle: Governor Christie acknowledging a “crisis in confidence,” sleepless nights, second-guessing and nonstop soul-searching.

Political apologies generally follow a robotic sequence. The public figure caught doing wrong offers a terse, often grudging, sometimes distant and always uncomfortable expression of remorse.

But Mr. Christie is not every other politician. He said “sorry” the Christie way: excessively, vaingloriously, in large, vivid and personal terms. At times, he divulged oddly intimate details and reactions — the 8 a.m. home workout session after which he discovered the “heartbreaking” news of his aide’s misconduct, and his late-night chats with his wife about the episode.

He seemed to want to talk the scandal away, droning on for so long at the State House that reporters started repeating their inquiries, even asking for his response to a news story that had popped up as he was talking.

“What was on display,” said Mike Murphy, a longtime Republican consultant who has advised former Gov. Mitt Romney, “were all the strengths of Chris Christie and all of the weaknesses.”

“He just does not come in small doses,” Mr. Murphy said.

Mr. Christie may have fielded every query tossed his way on Thursday (more than 90), but there remained scores of unanswered questions about his involvement in the imbroglio, which his forceful performance did little to satisfy.

Even as they marveled at his stamina, Republican leaders privately worried that Mr. Christie was cementing a reputation for the most unwelcome quality in the world of political professionals: unpredictability.

There were moments when the straight-talking governor seemed to slip into self-denial. Despite the absence of any concrete evidence, he suggested that perhaps there really had been a traffic study in progress when an aide in his office, working with a Christie appointee, closed lanes and paralyzed traffic in Fort Lee, N.J.

Mostly, he kept apologizing. Twenty times, in all. To the people of New Jersey. To the mayor of Fort Lee. To members of the State Legislature. Even to the news media. He kept finding new ways to flagellate himself, ticking off his “mistakes,” owning up to his “failure” and repeatedly declaring, “I was wrong.”

He seemed to lean on the lectern more than usual, holding himself steady and repeatedly fidgeting with his suit jacket.

His normally voluble and prosecutorial manner, the very attribute that has catapulted him onto the national political stage, was replaced by a newly contemplative and somber tone.

But this version of Chris Christie — the chastened, penitent public official — was hard to keep up, and he occasionally lapsed into a familiar pique.

When out-of-town reporters began to shout questions at him, disrupting his system of calling on journalists, the governor shot them a chilly stare. “Guys,” he said, “we don’t work that way.”

And his temper flared when he denounced, in harsh and scolding terms, the senior staff member who sent the email proposing “some traffic problems in Fort Lee” and who, he said, later misled him about her role.

“I am stunned by the abject stupidity that was shown here,” Mr. Christie said, making clear that he could no longer stand to be in the same room with the now-fired aide, Bridget Anne Kelly. “She was not given the opportunity to explain to me why she lied because it was so obvious that she had,” he said.

That candor won him praise from unexpected quarters. David Axelrod, President Obama’s longtime adviser, said that, at least during his televised appearance, Mr. Christie “came across as candid, regretful and accountable.”

The all but unending news conference seemed to offer Mr. Christie a cathartic public therapy session that was at once confessional and clinically detailed.

He expounded, professorially, on the nature of truth and the difficulty of detecting deceit.

“If you ask for something and someone deceives you and tells you it doesn’t exist, what’s the follow-up?” he asked. “Were you involved in any way? No. Any knowledge? No. Well, after that, what do you do?”

And he sought to clear up what he said were (at least to him) mystifying misimpressions about his temperament, mocking the idea that he becomes a “lunatic when he’s mad about something.”

“It is the rare moment,” he said, “when I raise my voice.”

Near the end of his question-and-answer session, a governor ever in touch with his emotional side acknowledged that he was still grappling with his own layered reactions to the controversy.

“I don’t know what the stages of grief are in exact order,” he said, “but I know anger gets there at some point. I’m sure I’ll have that, too.”

By MICHAEL BARBARO

He was, he said, heartbroken. Embarrassed. Sad. Disappointed. Humiliated.

By the end of an extraordinary and exhaustive 107-minute news conference, Chris Christie had transformed himself from a belligerent chief executive, famed for ridiculing his detractors, into a deeply wronged father figure, shaking his head, whispering his words and verging on tears.

The bravado had vanished. The certitude was gone.

In its place was an entirely new vocabulary of self-doubt and a once unthinkable spectacle: Governor Christie acknowledging a “crisis in confidence,” sleepless nights, second-guessing and nonstop soul-searching.

Political apologies generally follow a robotic sequence. The public figure caught doing wrong offers a terse, often grudging, sometimes distant and always uncomfortable expression of remorse.

But Mr. Christie is not every other politician. He said “sorry” the Christie way: excessively, vaingloriously, in large, vivid and personal terms. At times, he divulged oddly intimate details and reactions — the 8 a.m. home workout session after which he discovered the “heartbreaking” news of his aide’s misconduct, and his late-night chats with his wife about the episode.

He seemed to want to talk the scandal away, droning on for so long at the State House that reporters started repeating their inquiries, even asking for his response to a news story that had popped up as he was talking.

“What was on display,” said Mike Murphy, a longtime Republican consultant who has advised former Gov. Mitt Romney, “were all the strengths of Chris Christie and all of the weaknesses.”

“He just does not come in small doses,” Mr. Murphy said.

Mr. Christie may have fielded every query tossed his way on Thursday (more than 90), but there remained scores of unanswered questions about his involvement in the imbroglio, which his forceful performance did little to satisfy.

Even as they marveled at his stamina, Republican leaders privately worried that Mr. Christie was cementing a reputation for the most unwelcome quality in the world of political professionals: unpredictability.

There were moments when the straight-talking governor seemed to slip into self-denial. Despite the absence of any concrete evidence, he suggested that perhaps there really had been a traffic study in progress when an aide in his office, working with a Christie appointee, closed lanes and paralyzed traffic in Fort Lee, N.J.

Mostly, he kept apologizing. Twenty times, in all. To the people of New Jersey. To the mayor of Fort Lee. To members of the State Legislature. Even to the news media. He kept finding new ways to flagellate himself, ticking off his “mistakes,” owning up to his “failure” and repeatedly declaring, “I was wrong.”

He seemed to lean on the lectern more than usual, holding himself steady and repeatedly fidgeting with his suit jacket.

His normally voluble and prosecutorial manner, the very attribute that has catapulted him onto the national political stage, was replaced by a newly contemplative and somber tone.

But this version of Chris Christie — the chastened, penitent public official — was hard to keep up, and he occasionally lapsed into a familiar pique.

When out-of-town reporters began to shout questions at him, disrupting his system of calling on journalists, the governor shot them a chilly stare. “Guys,” he said, “we don’t work that way.”

And his temper flared when he denounced, in harsh and scolding terms, the senior staff member who sent the email proposing “some traffic problems in Fort Lee” and who, he said, later misled him about her role.

“I am stunned by the abject stupidity that was shown here,” Mr. Christie said, making clear that he could no longer stand to be in the same room with the now-fired aide, Bridget Anne Kelly. “She was not given the opportunity to explain to me why she lied because it was so obvious that she had,” he said.

That candor won him praise from unexpected quarters. David Axelrod, President Obama’s longtime adviser, said that, at least during his televised appearance, Mr. Christie “came across as candid, regretful and accountable.”

The all but unending news conference seemed to offer Mr. Christie a cathartic public therapy session that was at once confessional and clinically detailed.

He expounded, professorially, on the nature of truth and the difficulty of detecting deceit.

“If you ask for something and someone deceives you and tells you it doesn’t exist, what’s the follow-up?” he asked. “Were you involved in any way? No. Any knowledge? No. Well, after that, what do you do?”

And he sought to clear up what he said were (at least to him) mystifying misimpressions about his temperament, mocking the idea that he becomes a “lunatic when he’s mad about something.”

“It is the rare moment,” he said, “when I raise my voice.”

Near the end of his question-and-answer session, a governor ever in touch with his emotional side acknowledged that he was still grappling with his own layered reactions to the controversy.

“I don’t know what the stages of grief are in exact order,” he said, “but I know anger gets there at some point. I’m sure I’ll have that, too.”

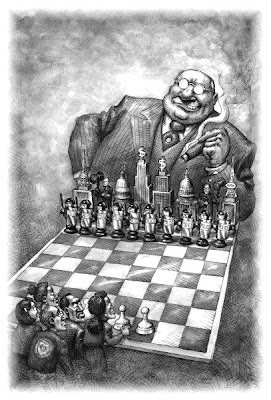

A credibility trap is a condition in which the financial, political and informational functions of a society have been compromised by corruption and fraud. The leadership cannot effectively reform, or even honestly address, the problems of that system without impairing and implicating, at least incidentally, a broad swath of the power structure, including themselves.

A credibility trap is a condition in which the financial, political and informational functions of a society have been compromised by corruption and fraud. The leadership cannot effectively reform, or even honestly address, the problems of that system without impairing and implicating, at least incidentally, a broad swath of the power structure, including themselves.

Comment