David Simon, creator of The Wire, near his office in Baltimore.

America is a country that is now utterly divided when it comes to its society, its economy, its politics. There are definitely two Americas. I live in one, on one block in Baltimore that is part of the viable America, the America that is connected to its own economy, where there is a plausible future for the people born into it. About 20 blocks away is another America entirely. It's astonishing how little we have to do with each other, and yet we are living in such proximity.

There's no barbed wire around West Baltimore or around East Baltimore, around Pimlico, the areas in my city that have been utterly divorced from the American experience that I know. But there might as well be. We've somehow managed to march on to two separate futures and I think you're seeing this more and more in the west. I don't think it's unique to America.

I think we've perfected a lot of the tragedy and we're getting there faster than a lot of other places that may be a little more reasoned, but my dangerous idea kind of involves this fellow who got left by the wayside in the 20th century and seemed to be almost the butt end of the joke of the 20th century; a fellow named Karl Marx.

I'm not a Marxist in the sense that I don't think Marxism has a very specific clinical answer to what ails us economically. I think Marx was a much better diagnostician than he was a clinician. He was good at figuring out what was wrong or what could be wrong with capitalism if it wasn't attended to and much less credible when it comes to how you might solve that.

You know if you've read Capital or if you've got the Cliff Notes, you know that his imaginings of how classical Marxism – of how his logic would work when applied – kind of devolve into such nonsense as the withering away of the state and platitudes like that. But he was really sharp about what goes wrong when capital wins unequivocally, when it gets everything it asks for.

That may be the ultimate tragedy of capitalism in our time, that it has achieved its dominance without regard to a social compact, without being connected to any other metric for human progress.

We understand profit. In my country we measure things by profit. We listen to the Wall Street analysts. They tell us what we're supposed to do every quarter. The quarterly report is God. Turn to face God. Turn to face Mecca, you know. Did you make your number? Did you not make your number? Do you want your bonus? Do you not want your bonus?

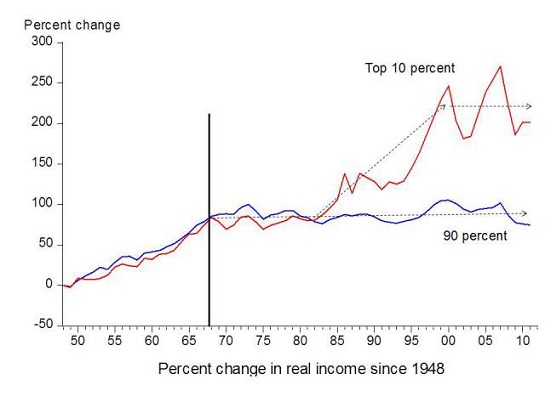

And that notion that capital is the metric, that profit is the metric by which we're going to measure the health of our society is one of the fundamental mistakes of the last 30 years. I would date it in my country to about 1980 exactly, and it has triumphed.

Capitalism stomped the hell out of Marxism by the end of the 20th century and was predominant in all respects, but the great irony of it is that the only thing that actually works is not ideological, it is impure, has elements of both arguments and never actually achieves any kind of partisan or philosophical perfection.

It's pragmatic, it includes the best aspects of socialistic thought and of free-market capitalism and it works because we don't let it work entirely. And that's a hard idea to think – that there isn't one single silver bullet that gets us out of the mess we've dug for ourselves. But man, we've dug a mess.

After the second world war, the west emerged with the American economy coming out of its wartime extravagance, emerging as the best product. It was the best product. It worked the best. It was demonstrating its might not only in terms of what it did during the war but in terms of just how facile it was in creating mass wealth.

Plus, it provided a lot more freedom and was doing the one thing that guaranteed that the 20th century was going to be – and forgive the jingoistic sound of this – the American century.

It took a working class that had no discretionary income at the beginning of the century, which was working on subsistence wages. It turned it into a consumer class that not only had money to buy all the stuff that they needed to live but enough to buy a bunch of shit that they wanted but didn't need, and that was the engine that drove us.

It wasn't just that we could supply stuff, or that we had the factories or know-how or capital, it was that we created our own demand and started exporting that demand throughout the west. And the standard of living made it possible to manufacture stuff at an incredible rate and sell it.

And how did we do that? We did that by not giving in to either side. That was the new deal. That was the great society. That was all of that argument about collective bargaining and union wages and it was an argument that meant neither side gets to win.

Labour doesn't get to win all its arguments, capital doesn't get to. But it's in the tension, it's in the actual fight between the two, that capitalism actually becomes functional, that it becomes something that every stratum in society has a stake in, that they all share.

The unions actually mattered. The unions were part of the equation. It didn't matter that they won all the time, it didn't matter that they lost all the time, it just mattered that they had to win some of the time and they had to put up a fight and they had to argue for the demand and the equation and for the idea that workers were not worth less, they were worth more.

Ultimately we abandoned that and believed in the idea of trickle-down and the idea of the market economy and the market knows best, to the point where now libertarianism in my country is actually being taken seriously as an intelligent mode of political thought. It's astonishing to me. But it is. People are saying I don't need anything but my own ability to earn a profit. I'm not connected to society. I don't care how the road got built, I don't care where the firefighter comes from, I don't care who educates the kids other than my kids. I am me. It's the triumph of the self. I am me, hear me roar.

That we've gotten to this point is astonishing to me because basically in winning its victory, in seeing that Wall come down and seeing the former Stalinist state's journey towards our way of thinking in terms of markets or being vulnerable, you would have thought that we would have learned what works. Instead we've descended into what can only be described as greed. This is just greed. This is an inability to see that we're all connected, that the idea of two Americas is implausible, or two Australias, or two Spains or two Frances.

Societies are exactly what they sound like. If everybody is invested and if everyone just believes that they have "some", it doesn't mean that everybody's going to get the same amount. It doesn't mean there aren't going to be people who are the venture capitalists who stand to make the most. It's not each according to their needs or anything that is purely Marxist, but it is that everybody feels as if, if the society succeeds, I succeed, I don't get left behind. And there isn't a society in the west now, right now, that is able to sustain that for all of its population.

And so in my country you're seeing a horror show. You're seeing a retrenchment in terms of family income, you're seeing the abandonment of basic services, such as public education, functional public education. You're seeing the underclass hunted through an alleged war on dangerous drugs that is in fact merely a war on the poor and has turned us into the most incarcerative state in the history of mankind, in terms of the sheer numbers of people we've put in American prisons and the percentage of Americans we put into prisons. No other country on the face of the Earth jails people at the number and rate that we are.

We have become something other than what we claim for the American dream and all because of our inability to basically share, to even contemplate a socialist impulse.

Socialism is a dirty word in my country. I have to give that disclaimer at the beginning of every speech, "Oh by the way I'm not a Marxist you know". I lived through the 20th century. I don't believe that a state-run economy can be as viable as market capitalism in producing mass wealth. I don't.

I'm utterly committed to the idea that capitalism has to be the way we generate mass wealth in the coming century. That argument's over. But the idea that it's not going to be married to a social compact, that how you distribute the benefits of capitalism isn't going to include everyone in the society to a reasonable extent, that's astonishing to me.

And so capitalism is about to seize defeat from the jaws of victory all by its own hand. That's the astonishing end of this story, unless we reverse course. Unless we take into consideration, if not the remedies of Marx then the diagnosis, because he saw what would happen if capital triumphed unequivocally, if it got everything it wanted.

And one of the things that capital would want unequivocally and for certain is the diminishment of labour. They would want labour to be diminished because labour's a cost. And if labour is diminished, let's translate that: in human terms, it means human beings are worth less.

From this moment forward unless we reverse course, the average human being is worth less on planet Earth. Unless we take stock of the fact that maybe socialism and the socialist impulse has to be addressed again; it has to be married as it was married in the 1930s, the 1940s and even into the 1950s, to the engine that is capitalism.

Mistaking capitalism for a blueprint as to how to build a society strikes me as a really dangerous idea in a bad way. Capitalism is a remarkable engine again for producing wealth. It's a great tool to have in your toolbox if you're trying to build a society and have that society advance. You wouldn't want to go forward at this point without it. But it's not a blueprint for how to build the just society. There are other metrics besides that quarterly profit report.

The idea that the market will solve such things as environmental concerns, as our racial divides, as our class distinctions, our problems with educating and incorporating one generation of workers into the economy after the other when that economy is changing; the idea that the market is going to heed all of the human concerns and still maximise profit is juvenile. It's a juvenile notion and it's still being argued in my country passionately and we're going down the tubes. And it terrifies me because I'm astonished at how comfortable we are in absolving ourselves of what is basically a moral choice. Are we all in this together or are we all not?

If you watched the debacle that was, and is, the fight over something as basic as public health policy in my country over the last couple of years, imagine the ineffectiveness that Americans are going to offer the world when it comes to something really complicated like global warming. We can't even get healthcare for our citizens on a basic level. And the argument comes down to: "Goddamn this socialist president. Does he think I'm going to pay to keep other people healthy? It's socialism, motherfucker."

What do you think group health insurance is? You know you ask these guys, "Do you have group health insurance where you …?" "Oh yeah, I get …" you know, "my law firm …" So when you get sick you're able to afford the treatment.

The treatment comes because you have enough people in your law firm so you're able to get health insurance enough for them to stay healthy. So the actuarial tables work and all of you, when you do get sick, are able to have the resources there to get better because you're relying on the idea of the group. Yeah. And they nod their heads, and you go "Brother, that's socialism. You know it is."

And ... you know when you say, OK, we're going to do what we're doing for your law firm but we're going to do it for 300 million Americans and we're going to make it affordable for everybody that way. And yes, it means that you're going to be paying for the other guys in the society, the same way you pay for the other guys in the law firm … Their eyes glaze. You know they don't want to hear it. It's too much. Too much to contemplate the idea that the whole country might be actually connected.

So I'm astonished that at this late date I'm standing here and saying we might want to go back for this guy Marx that we were laughing at, if not for his prescriptions, then at least for his depiction of what is possible if you don't mitigate the authority of capitalism, if you don't embrace some other values for human endeavour.

And that's what The Wire was about basically, it was about people who were worth less and who were no longer necessary, as maybe 10 or 15% of my country is no longer necessary to the operation of the economy. It was about them trying to solve, for lack of a better term, an existential crisis. In their irrelevance, their economic irrelevance, they were nonetheless still on the ground occupying this place called Baltimore and they were going to have to endure somehow.

That's the great horror show. What are we going to do with all these people that we've managed to marginalise? It was kind of interesting when it was only race, when you could do this on the basis of people's racial fears and it was just the black and brown people in American cities who had the higher rates of unemployment and the higher rates of addiction and were marginalised and had the shitty school systems and the lack of opportunity.

And kind of interesting in this last recession to see the economy shrug and start to throw white middle-class people into the same boat, so that they became vulnerable to the drug war, say from methamphetamine, or they became unable to qualify for college loans. And all of a sudden a certain faith in the economic engine and the economic authority of Wall Street and market logic started to fall away from people. And they realised it's not just about race, it's about something even more terrifying. It's about class. Are you at the top of the wave or are you at the bottom?

So how does it get better? In 1932, it got better because they dealt the cards again and there was a communal logic that said nobody's going to get left behind. We're going to figure this out. We're going to get the banks open. From the depths of that depression a social compact was made between worker, between labour and capital that actually allowed people to have some hope.

We're either going to do that in some practical way when things get bad enough or we're going to keep going the way we're going, at which point there's going to be enough people standing on the outside of this mess that somebody's going to pick up a brick, because you know when people get to the end there's always the brick. I hope we go for the first option but I'm losing faith.

The other thing that was there in 1932 that isn't there now is that some element of the popular will could be expressed through the electoral process in my country.

The last job of capitalism – having won all the battles against labour, having acquired the ultimate authority, almost the ultimate moral authority over what's a good idea or what's not, or what's valued and what's not – the last journey for capital in my country has been to buy the electoral process, the one venue for reform that remained to Americans.

Right now capital has effectively purchased the government, and you witnessed it again with the healthcare debacle in terms of the $450m that was heaved into Congress, the most broken part of my government, in order that the popular will never actually emerged in any of that legislative process.

So I don't know what we do if we can't actually control the representative government that we claim will manifest the popular will. Even if we all start having the same sentiments that I'm arguing for now, I'm not sure we can effect them any more in the same way that we could at the rise of the Great Depression, so maybe it will be the brick. But I hope not.

David Simon is an American author and journalist and was the executive producer of The Wire. This is an edited extract of a talk delivered at the Festival of Dangerous Ideas in Sydney.

Comment