We’ve long said that the greatest short-term threat to humanity is from the fuel pools at Fukushima.

The Japanese nuclear agency recently green-lighted the removal of the spent fuel rods from Fukushima reactor 4′s spent fuel pool. The operation is scheduled to begin this month.

The head of the U.S. Department of Energy correctly notes:

The success of the cleanup also has global significance. So we all have a direct interest in seeing that the next steps are taken well, efficiently and safely.

If one of the pools collapsed or caught fire, it could have severe adverse impacts not only on Japan … but the rest of the world, including the United States. Indeed, a Senator called it a national security concern for the U.S.:

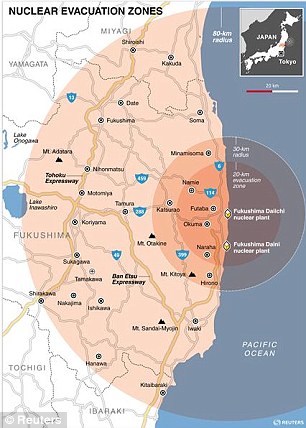

The radiation caused by the failure of the spent fuel pools in the event of another earthquake could reach the West Coast within days. That absolutely makes the safe containment and protection of this spent fuel a security issue for the United States.

Award-winning scientist David Suzuki says that Fukushima is terrifying, Tepco and the Japanese government are lying through their teeth, and Fukushima is “the most terrifying situation I can imagine”.

Suzuki notes that reactor 4 is so badly damaged that – if there’s another earthquake of 7 or above – the building could come down. And the probability of another earthquake of 7 or above in the next 3 years is over 95%.

Suzuki says that he’s seen a paper that says that if – in fact – the 4th reactor comes down, “it’s bye bye Japan, and everyone on the West Coast of North America should evacuate. Now if that’s not terrifying, I don’t know what is.”

The Telegraph reports:

The operator of Japan’s crippled Fukushima nuclear power plant … will begin a dry run of the procedure at the No. 4 reactor, which experts have warned carries grave risks.

***

“Did you ever play pick up sticks?” asked a foreign nuclear expert who has been monitoring Tepco’s efforts to regain control of the plant. “You had 50 sticks, you heaved them into the air and than had to take one off the pile at a time.

“If the pile collapsed when you were picking up a stick, you lost,” he said. “There are 1,534 pick-up sticks in a jumble in top of an unsteady reactor 4. What do you think can happen?

“I do not know anyone who is confident that this can be done since it has never been tried.”

***

“Did you ever play pick up sticks?” asked a foreign nuclear expert who has been monitoring Tepco’s efforts to regain control of the plant. “You had 50 sticks, you heaved them into the air and than had to take one off the pile at a time.

“If the pile collapsed when you were picking up a stick, you lost,” he said. “There are 1,534 pick-up sticks in a jumble in top of an unsteady reactor 4. What do you think can happen?

“I do not know anyone who is confident that this can be done since it has never been tried.”

ABC reports:

One slip-up in the latest step to decommission Japan’s crippled Fukushima nuclear plant could trigger a “monumental” chain reaction, experts warn.

***

Experts around the world have warned … that the fuel pool is in a precarious state – vulnerable to collapsing in another big earthquake.

Yale University professor Charles Perrow wrote about the number 4 fuel pool this year in the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists.

“This has me very scared,” he told the ABC.

“Tokyo would have to be evacuated because [the] caesium and other poisons that are there will spread very rapidly.

***

Experts around the world have warned … that the fuel pool is in a precarious state – vulnerable to collapsing in another big earthquake.

Yale University professor Charles Perrow wrote about the number 4 fuel pool this year in the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists.

“This has me very scared,” he told the ABC.

“Tokyo would have to be evacuated because [the] caesium and other poisons that are there will spread very rapidly.

Perrow also argues:

Conditions in the unit 4 pool, 100 feet from the ground, are perilous, and if any two of the rods touch it could cause a nuclear reaction that would be uncontrollable. The radiation emitted from all these rods, if they are not continually cool and kept separate, would require the evacuation of surrounding areas including Tokyo. Because of the radiation at the site the 6,375 rods in the common storage pool could not be continuously cooled; they would fission and all of humanity will be threatened, for thousands of years.

Former Japanese ambassador Akio Matsumura warns that – if the operation isn’t done right – this could one day be considered the start of “the ultimate catastrophe of the world and planet”:

(He also argues that removing the fuel rods will take “decades rather than months.)

Nuclear expert Arnie Gundersen and physician Helen Caldicott have both said that people should evacuate the Northern Hemisphere if one of the Fukushima fuel pools collapses. Gundersen said:

Move south of the equator if that ever happened, I think that’s probably the lesson there.

Harvey Wasserman wrote two months ago:

We are now within two months of what may be humankind’s most dangerous moment since the Cuban Missile Crisis.

***

Should the attempt fail, the rods could be exposed to air and catch fire, releasing horrific quantities of radiation into the atmosphere. The pool could come crashing to the ground, dumping the rods together into a pile that could fission and possibly explode. The resulting radioactive cloud would threaten the health and safety of all us.

***

A new fuel fire at Unit 4 would pour out a continuous stream of lethal radioactive poisons for centuries.

Former Ambassador Mitsuhei Murata says full-scale releases from Fukushima “would destroy the world environment and our civilization. This is not rocket science, nor does it connect to the pugilistic debate over nuclear power plants. This is an issue of human survival.”

***

Should the attempt fail, the rods could be exposed to air and catch fire, releasing horrific quantities of radiation into the atmosphere. The pool could come crashing to the ground, dumping the rods together into a pile that could fission and possibly explode. The resulting radioactive cloud would threaten the health and safety of all us.

***

A new fuel fire at Unit 4 would pour out a continuous stream of lethal radioactive poisons for centuries.

Former Ambassador Mitsuhei Murata says full-scale releases from Fukushima “would destroy the world environment and our civilization. This is not rocket science, nor does it connect to the pugilistic debate over nuclear power plants. This is an issue of human survival.”

Even Japan’s Top Nuclear Regulator Says that The Operation Carries a “Very Large Risk Potential”

Even the head of Japan’s nuclear agency is worried. USA Today notes:

Nuclear regulatory chairman Shunichi Tanaka, however, warned that removing the fuel rods from Unit 4 would be difficult because of the risk posed by debris that fell into the pool during the explosions.

“It’s a totally different operation than removing normal fuel rods from a spent fuel pool,” Tanaka said at a regular news conference. “They need to be handled extremely carefully and closely monitored. You should never rush or force them out, or they may break.”

He said it would be a disaster if fuel rods are pulled forcibly and are damaged or break open when dropped from the pool, located about 30 meters (100 feet) above ground, releasing highly radioactive material. “I’m much more worried about this than contaminated water,” Tanaka said

“It’s a totally different operation than removing normal fuel rods from a spent fuel pool,” Tanaka said at a regular news conference. “They need to be handled extremely carefully and closely monitored. You should never rush or force them out, or they may break.”

He said it would be a disaster if fuel rods are pulled forcibly and are damaged or break open when dropped from the pool, located about 30 meters (100 feet) above ground, releasing highly radioactive material. “I’m much more worried about this than contaminated water,” Tanaka said

The same top Japanese nuclear official said:

The process involves a very large risk potential.

BBC reports:

A task of extraordinary delicacy and danger is about to begin at Japan’s Fukushima nuclear power station.

***

One senior official told me: “It’s going to be very difficult but it has to happen.”

Why It’s Such a Difficult Operation***

One senior official told me: “It’s going to be very difficult but it has to happen.”

CNN notes that debris in the fuel pool might interfere with operations:

South China Morning Post notes:

Nothing remotely similar has been attempted before and … it is feared that any error of judgment could lead to a massive release of radiation into the atmosphere.

***

A spokesman for Tepco … admitted, however, that it was not clear whether any of the rods were damaged or if debris in the pool would complicate the recovery effort.

***

A spokesman for Tepco … admitted, however, that it was not clear whether any of the rods were damaged or if debris in the pool would complicate the recovery effort.

Professor Richard Broinowski – former Australian Ambassador to Vietnam, Republic of Korea, Mexico, the Central American Republics and Cuba – and author of numerous books on nuclear policy and Fukushima, says some of the fuel rods are probably fused.

Murray E. Jennex, Ph.D., P.E. (Professional Engineer), Professor of MIS, San Diego State University, notes:

The rods in the spent fuel pool may have melted …. I consider it more likely that these rods were breached during the explosions associated with the event and their contents may be in contact with the ground water, probably due to all the seawater that was sprayed on the plant.

Fuel rod expert Arnie Gundersen – a nuclear engineer and former senior manager of a nuclear power company which manufactured nuclear fuel rods – recently explained the biggest problem with the fuel rods (at 15:45):

I think they’re belittling the complexity of the task. If you think of a nuclear fuel rack as a pack of cigarettes, if you pull a cigarette straight up it will come out — but these racks have been distorted. Now when they go to pull the cigarette straight out, it’s going to likely break and release radioactive cesium and other gases, xenon and krypton, into the air. I suspect come November, December, January we’re going to hear that the building’s been evacuated, they’ve broke a fuel rod, the fuel rod is off-gassing.

***

***

I suspect we’ll have more airborne releases as they try to pull the fuel out. If they pull too hard, they’ll snap the fuel. I think the racks have been distorted, the fuel has overheated — the pool boiled – and the net effect is that it’s likely some of the fuel will be stuck in there for a long, long time.

In another interview, Gundersen provides additional details (at 31:00):

The racks are distorted from the earthquake — oh, by the way, the roof has fallen in, which further distorted the racks.

The net effect is they’ve got the bundles of fuel, the cigarettes in these racks, and as they pull them out, they’re likely to snap a few. When you snap a nuclear fuel rod, that releases radioactivity again, so my guess is, it’s things like krypton-85, which is a gas, cesium will also be released, strontium will be released. They’ll probably have to evacuate the building for a couple of days. They’ll take that radioactive gas and they’ll send it up the stack, up into the air, because xenon can’t be scrubbed, it can’t be cleaned, so they’ll send that radioactive xenon up into the air and purge the building of all the radioactive gases and then go back in and try again.

It’s likely that that problem will exist on more than one bundle. So over the next year or two, it wouldn’t surprise me that either they don’t remove all the fuel because they don’t want to pull too hard, or if they do pull to hard, they’re likely to damage the fuel and cause a radiation leak inside the building. So that’s problem #2 in this process, getting the fuel out of Unit 4 is a top priority I have, but it’s not going to be easy. Tokyo Electric is portraying this as easy. In a normal nuclear reactor, all of this is done with computers. Everything gets pulled perfectly vertically. Well nothing is vertical anymore, the fuel racks are distorted, it’s all going to have to be done manually. The net effect is it’s a really difficult job. It wouldn’t surprise me if they snapped some of the fuel and they can’t remove it.

The net effect is they’ve got the bundles of fuel, the cigarettes in these racks, and as they pull them out, they’re likely to snap a few. When you snap a nuclear fuel rod, that releases radioactivity again, so my guess is, it’s things like krypton-85, which is a gas, cesium will also be released, strontium will be released. They’ll probably have to evacuate the building for a couple of days. They’ll take that radioactive gas and they’ll send it up the stack, up into the air, because xenon can’t be scrubbed, it can’t be cleaned, so they’ll send that radioactive xenon up into the air and purge the building of all the radioactive gases and then go back in and try again.

It’s likely that that problem will exist on more than one bundle. So over the next year or two, it wouldn’t surprise me that either they don’t remove all the fuel because they don’t want to pull too hard, or if they do pull to hard, they’re likely to damage the fuel and cause a radiation leak inside the building. So that’s problem #2 in this process, getting the fuel out of Unit 4 is a top priority I have, but it’s not going to be easy. Tokyo Electric is portraying this as easy. In a normal nuclear reactor, all of this is done with computers. Everything gets pulled perfectly vertically. Well nothing is vertical anymore, the fuel racks are distorted, it’s all going to have to be done manually. The net effect is it’s a really difficult job. It wouldn’t surprise me if they snapped some of the fuel and they can’t remove it.

The Japan Times writes:

The consequences could be far more severe than any nuclear accident the world has ever seen. If a fuel rod is dropped, breaks or becomes entangled while being removed, possible worst case scenarios include a big explosion, a meltdown in the pool, or a large fire. Any of these situations could lead to massive releases of deadly radionuclides into the atmosphere, putting much of Japan — including Tokyo and Yokohama — and even neighboring countries at serious risk.

CNN reports:

[Mycle Schneider, nuclear consultant:] The situation could still get a lot worse. A massive spent fuel fire would likely dwarf the current dimensions of the catastrophe and could exceed the radioactivity releases of Chernobyl dozens of times.

Reuters notes:

Experts question whether it will be able to pull off the removal of all the assemblies successfully.***

No one knows how bad it can get, but independent consultants Mycle Schneider and Antony Froggatt said recently in their World Nuclear Industry Status Report 2013: “Full release from the Unit-4 spent fuel pool, without any containment or control, could cause by far the most serious radiological disaster to date.”

***

Nonetheless, Tepco inspires little confidence. Sharply criticized for failing to protect the Fukushima plant against natural disasters, its handling of the crisis since then has also been lambasted.

***

“There is a risk of an inadvertent criticality if the bundles are distorted and get too close to each other,” Gundersen said.

***

The rods are also vulnerable to fire should they be exposed to air, Gundersen said. [The pools have already boiled due to exposure to air.]

***

[Here is a visual tour of Fukushima's fuel pools, along with graphics of how the rods will be removed.]

Tepco confirmed the Reactor No. 4 fuel pool contains debris during an investigation into the chamber earlier this month.

Removing the rods from the pool is a delicate task normally assisted by computers, according to Toshio Kimura, a former Tepco technician, who worked at Fukushima Daiichi for 11 years.

“Previously it was a computer-controlled process that memorized the exact locations of the rods down to the millimeter and now they don’t have that. It has to be done manually so there is a high risk that they will drop and break one of the fuel rods,” Kimura said.

***

Corrosion from the salt water will have also weakened the building and equipment, he said.

No one knows how bad it can get, but independent consultants Mycle Schneider and Antony Froggatt said recently in their World Nuclear Industry Status Report 2013: “Full release from the Unit-4 spent fuel pool, without any containment or control, could cause by far the most serious radiological disaster to date.”

***

Nonetheless, Tepco inspires little confidence. Sharply criticized for failing to protect the Fukushima plant against natural disasters, its handling of the crisis since then has also been lambasted.

***

“There is a risk of an inadvertent criticality if the bundles are distorted and get too close to each other,” Gundersen said.

***

The rods are also vulnerable to fire should they be exposed to air, Gundersen said. [The pools have already boiled due to exposure to air.]

***

[Here is a visual tour of Fukushima's fuel pools, along with graphics of how the rods will be removed.]

Tepco confirmed the Reactor No. 4 fuel pool contains debris during an investigation into the chamber earlier this month.

Removing the rods from the pool is a delicate task normally assisted by computers, according to Toshio Kimura, a former Tepco technician, who worked at Fukushima Daiichi for 11 years.

“Previously it was a computer-controlled process that memorized the exact locations of the rods down to the millimeter and now they don’t have that. It has to be done manually so there is a high risk that they will drop and break one of the fuel rods,” Kimura said.

***

Corrosion from the salt water will have also weakened the building and equipment, he said.

ABC Radio Australia quotes an expert on the situation (at 1:30):

Richard Tanter, expert on nuclear power issues and professor of international relations at the University of Melbourne:

***

Reactor Unit 4, the one which has a very large amount of stored fuel in its fuel storage pool, that is sinking. According to former prime Minister Kan Naoto, that has sunk some 31 inches in places and it’s not uneven.

***

Reactor Unit 4, the one which has a very large amount of stored fuel in its fuel storage pool, that is sinking. According to former prime Minister Kan Naoto, that has sunk some 31 inches in places and it’s not uneven.

And Chris Harris – a, former licensed Senior Reactor Operator and engineer – notes that it doesn’t help that a lot of the rods are in very fragile condition:

Although there are a lot of spent fuel assemblies in there which could achieve criticality — there are also 200 new fuel assemblies which have equivalent to a full tank of gas, let’s call it that. Those are the ones most likely to go critical first.

***

Some pictures that were released recently show that a lot of fuel is damaged, so when they go ahead and put the grapple on it, and they pull it up, it’s going to fall apart. The boreflex has been eaten away; it doesn’t take saltwater very good.

Nuclear engineers say that the fuel pool is “distorted”, material was blown up into air and came down inside, damaging the fuel, the roof fell in, distorting things inside.

Indeed, Fukushima documents discuss “fuel that is severely damaged” inside cooling pool, and show illustrations of “deformed or leaking fuels”.

The Urgent Need: Replace Tepco

Tepco is incompetent and corrupt. As such, it is the last company which should be in charge of the clean-up.

Top scientists and government officials say that Tepco should be removed from all efforts to stabilize Fukushima. An international team of the smartest engineers and scientists should handle this difficult “surgery”.

Bloomberg notes:

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe is being told by his own party that Japan’s response is failing. Plant operator [Tepco] alone isn’t up to the task of managing the cleanup and decommissioning of the atomic station in Fukushima. That’s the view of Tadamori Oshima, head of a task force in charge of Fukushima’s recovery and former vice president of Abe’s Liberal Democratic Party.

***

[There's] a growing recognition that the government needs to take charge at the Fukushima station…. “If we allow the situation to continue, it’ll never be resolved” [said Sumio Mabuchi, a government point man on crisis in 2011].

Comment