Monopoly Goes Corporate

The Landlord’s Game, created by the fiery stenographer, poet and feminist Lizzie Magie, was a predecessor of the board game Monopoly.

By MARY PILON

IT’S been a rough summer for Monopoly purists. In July, the board game community became incensed by the introduction of Monopoly Empire, the latest flavor of the iconic game; this one substitutes traditional Atlantic City property names with those of large corporations — McDonald’s, Coca-Cola, Samsung and Nestlé, to name a few. In the latest Monopoly game, players acquire key brands to create corporate empires rather than try to bankrupt their opponents. And the old tokens — the racecar, thimble and top hat that used to race around the board — have been replaced by a 2014 Corvette Stingray, an Xbox controller and a Paramount Pictures movie clapboard.

Hardly cosmetic, the changes introduce a whole new animating ideology to a game created to critique, not celebrate, corporate America. Contrary to popular board game lore, Monopoly was invented not by an unemployed man during the Great Depression but in 1903 by a feminist who lived in the Washington, D.C., area and wanted to teach about the evils of monopolization. Her name was Lizzie Magie.

Seventeen years before women could vote, Ms. Magie, a fiery stenographer, poet, sometime actress and onetime employee of the United States Postal Service’s dead-letter office, ginned up a game that mirrored what she perceived to be the vast economic inequalities of her day. She called it the Landlord’s Game and saw it as an educational tool and gamy rebellion against the era’s corporate titans, John D. Rockefeller Sr., Andrew Carnegie and J. P. Morgan.

Ms. Magie was an ardent follower of Henry George, who advocated a single tax on land. She cleverly designed two sets of rules: one in which the object was to get rich quick, the other as an anti-monopoly game in which all players benefited from wealth created. Historical evidence suggests that the more vice-laden monopolist game resonated with earlier players. “It is a practical demonstration of the present system of land-grabbing with all its usual outcomes and consequences,” Ms. Magie told The Single Tax Review in 1902. “It might well have been called the Game of Life, as it contains all the elements of success and failure in the real world, and the object is the same as the human race in general seem to have, i.e., the accumulation of wealth.”

Early boards, uncovered a generation later by the economist Ralph Anspach’s “Anti-Monopoly” lawsuit against Parker Brothers, which was acquired by Hasbro in 1991, reveal that modified monopoly games were common and were embraced by early counterculture players. A game dating to Arden, Del., in 1903 has a George Street and New York properties like the Bowery and Central Park on the place on the board many today know as Free Parking. A board played on in 1909 in Altoona, Pa., made nods to its map with Kettle and Lloyd Streets.

From Ms. Magie’s patent, the “monopoly game” spread among left-wing intellectuals for decades. It was embraced in Arden, a single tax bohemian enclave that attracted Upton Sinclair and the radical scholar Scott Nearing. Rexford G. Tugwell, a Columbia University professor and member of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “brain trust,” played and taught the game. Members of the administration of Mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia of New York played it, as did Ernest Angell, an attorney and chairman of the board at the American Civil Liberties Union, according to his son, Roger Angell.

Atlantic City Quakers introduced some of the greatest modifications to the early monopoly game. The Quakers, who value silence, scuttled the auction system of property acquisition in the 1930s and instead put fixed sale prices on the board, which made it easier to play with children. And the Quakers replaced drab pawns with miscellaneous objects, later mass-produced by Dowst, a Chicago-based company that created Cracker Jack prizes.

The Quakers’ Atlantic City board serves as an odd reflection of the city’s overlooked cartography. Atlantic’s City’s Boardwalk was a spectacle of rolling chairs, theater and fashion, and its pageantry later inspired Walt Disney as he designed modern theme parks. Baltic and Mediterranean Avenues. the cheapest properties on the board, were largely black neighborhoods in Atlantic City when much of the Jim Crow South migrated north, where black citizens staffed gleaming hotels and restaurants that refused to serve them. The Reading Railroad shuttled pleasure seekers between Philadelphia and Atlantic City, and New York Avenue became home to one of the country’s earliest gay scenes.

It was a version of this Atlantic City game that Charles Darrow learned to play, and eventually sold the concept to Parker Brothers, which marketed it to the masses in 1935. The game’s early social history was then largely forgotten.

Without realizing it, Mr. Anspach’s Anti-Monopoly, a game that heralded trustbusters and railed against OPEC during the 1970s, was a return to the game’s progressive roots. Mr. Anspach fully researched the game and its origins during the course of a 10-year legal battle that, among other things, called into question whether Parker Brothers had illegitimately monopolized Monopoly. The suit ultimately reached the Supreme Court, and in the end, Mr. Anspach won the right to sell his Anti-Monopoly game.

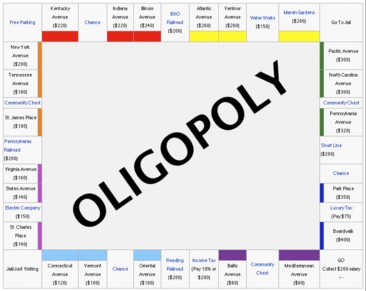

Today many local “-opoly” games are available; unlike the original games, which were hand drawn on oil cloth, these new versions are mass produced (some parts in China) with licenses from Hasbro. While changes to Monopoly’s essence (including the recent ousting of the iron token) may cause grumblings, they remind us that board games (like books, movies or video games) reflect an ever-changing national conversation. Milton Bradley’s 19th-century Checkered Game of Life had spaces for Intemperance, Suicide and Idleness, and players aspired to “Happy Old Age,” not to the plastic mansion at the end of today’s game. Cluedo, the British parent to Clue, deployed darker weapons like a hypodermic needle and a bottle of poison and a Reverend Green character who could be accused of murder.

Monopoly, too, will continue its cardboard evolution, even as traditionalists decry Monopoly Empire. The game will likely continue to evolve, as will those who play it.

Mary Pilon is a sports reporter at The New York Times and the author of the forthcoming book “The Monopolists,” about the hidden history of the game.

Comment