By STEVEN HELLER

Graphic design is an art best served as ink on paper. Despite the inevitable transition to digital media, a devoted connoisseur still prefers to hold a beautifully printed book, letterhead or brochure. David Jury, an English design scholar whose previous book, “Letter*press: The Allure of the Handmade,” revealed his obsession with the kiss of hot metal type on sheets of hand-*printed paper, has been collecting artifacts of the “black art” for decades. I’m not talking about occultist paraphernalia but rather 19th- and early-20th-century “jobbing” — which is to say, commercial — printing specimens. As he notes in GRAPHIC DESIGN BEFORE GRAPHIC DESIGNERS: The Printer as Designer and Craftsman 1700-1914 (Thames & Hudson, $60), “To the public, printing was a mysterious process, even magical.”

Jury is not simply a collector with a sophisticated eye for printed work; he expertly catalogs and chronicles his findings, attempting to place these objects in the cultural and commercial continuum. With an emphasis on Britain and the United States, his stunning new book is the first full-scale history of the printers, sign-writers, engravers and punch-cutters who — before the early 20th century, when the term “graphic design” was coined — did all the same things that today’s designers do, with incomparable skill.

The objects of his inspection are, for the most part, at the intersection of technology, commerce and culture. More than 300 years after the invention of printing, the 19th century was an era of design enlightenment. The commercial art and craft of graphic and typographic activity was prodigiously practiced by trained artisans who drew their inspiration from many of the same sources. Printers and type foundries published scores of elaborate sample books — some so ornate they resembled family Bibles, others stuffed like scrapbooks with samples hot off the presses.

Contemporary artists and designers sometimes think this material is merely quaint, or else they turn up their noses altogether at this decorative stuff, but a simple scan of Jury’s reproductions shows that the men (and the few women) who worked in this field knew exactly what they were doing. This is not naďve art. What they knew how to do was decidedly more difficult than using layout, font and drawing programs on today’s computers. The high level of sophistication can be seen in specimens like an excessively decorated ad for a 12-color press (“Golding’s Chromatic Jobber,” circa 1886) that demanded a lot of patience as well as aptitude to achieve the final result. And the eccentric typography on the cover of a specimen book by Thomas Hailing elegantly employs a quirky ornate typeface that prefigures everything from psyche*deliato today’s comics.

Any lettering aficionado will be stimulated by the very sight of these Victorian-era artifacts, which include the rainbow-colored ad for the Northern Pacific line, with more than a dozen different typefaces composed harmoniously on a single poster. Or the high-intensity Rocky Mountain News Printing Company advertisement, which combines multiple patterns and various contoured and illustrated letters together in one “logo type.” Each printer attempted to outdo all the others: the more presswork or detailed intricacy the better. And Jury, for his part, has outdone any other book I know that is devoted to this material. Through his keen selections and careful research, he powerfully presents the origins of today’s graphic design.

The typographic and ornamental work produced by these “proto-designers” in the pre-computer world has a corollary in what I call the “neo-designers” in the computer coding world. In the beautifully illustrated GENERATIVE DESIGN: Visualize, Program, and Create With Processing (Princeton Architectural Press, $100), the authors, Hartmut Bohnacker, Benedikt Gross and Julia Laub, and the editor, Claudius Lazzeroni, examine through case studies and step-by-step instructionals how various coding and programming languages have resulted in new definitions of the design process, much in the way that the “black art” did two centuries before. Those who generate art, animation and even new typefaces from algorithms would not necessarily have been considered graphic designers in the analog environment, but they are becoming a new breed of *designer/engineer in the digital era.

Although I’m personally more comfortable with analog design methods, this book is a fine introduction to generative design, filled with impressive examples and thankfully free of mind-*numbing jargon. For instance, “Growing Data,” a research project by the designer Cedric Kiefer, explores how natural processes can generate new forms of data visualization, going beyond traditional statistical charts. Virtual plant growth can be used to visualize air quality in cities. “Just as external influences determine the growth of plants, data that varies can control aspects of digital growth,” the authors write. Bits of information are assigned to variables connected to the plant’s change in size or density, slowly generating words or symbols. Another fascinating case study involves Jonathan Puckey’s “Tile Tool,” which aims to provide “a connection between the automation of work and the individual ideas and energy of the designer.” Using Tile Tool, the designer draws free-form shapes that are composed of preformed tiles. The result is a “balance between opportunities and constraints.” And “Similar Diversity,” by Andreas Koller and Philipp Steinweber, is a chart “that visualizes parts of the holy scriptures of the five main world religions” by counting how many times a figure is mentioned, for example, and showing each figure’s activities through a color-coded list of frequently used verbs.

Considering that the market for information and data visualization is growing exponentially, confounding our ability to digest everything that’s thrown at us, generative design is helping us find new ways to express information with novel metaphors. This book, equal parts art and textbook, is a valuable tool for both learning what exists and triggering new ideas.

Generative design is one part of what appears to be a larger movement of designers and artists trying to make science more accessible to the lay public. VISUAL STRATEGIES: A Practical Guide to Graphics for Scientists and Engineers (Yale University, $35) is the result of conversations its co-authors, Felice C. Frankel and Angela H. DePace, had with the designer Stefan Sagmeister about how to illustrate theories and formulas so as not to trivialize complex ideas. The book is divided into tabbed sections, including “Form and Structure,” “Process and Time,” “Compare and Contrast,” “Interactive Graphics” and more. Each contains various examples of how concepts like “growth in root hair cells” and “butterfly wing patterns” can be translated into images through graphical tools.

While the book itself is smartly and accessibly designed by Sagmeister’s studio in New York, the examples are not always the most sophisticated compositions. Which is perhaps the point. “The process of making a visual representation requires you to clarify your thinking and improve your ability to communicate with others,” write Frankel, a science photographer and research scientist at M.I.T., and DePace, a biologist at Harvard. Whether the result is a complex diagram produced using generative design techniques or a simple napkin sketch of a complex process, scientists must understand who their audience is and, in turn, create images their audience can understand.

What existed before the big bang?

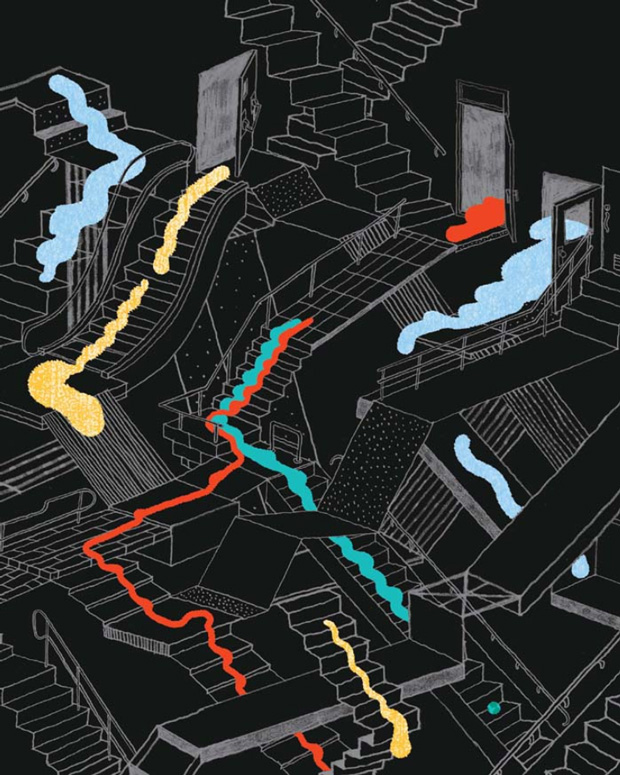

Illustrated by Josh Cochran

The intersection of art and science is covered more symbolically and metaphysically in THE WHERE, THE WHY, AND THE HOW: 75 Artists Illustrate Wondrous Mysteries of Science (Chronicle Books, $24.95), by Jenny Volvovski, Julia Rothman and Matt Lamothe. More than 50 scientists were asked to explore “unanswered questions” like “What is dark matter?,” “Why do we hiccup?,” “Do trees talk to each other?” and “Why do we fall for optical illusions?” Then each question is illustrated by the invited artists. Rather than visual explanations, the results are conceptual, metaphorical and allegorical interpretations. Some of the drawings and paintings are decidedly satiric, such as David Heatley’s response to “How can cancer be such a biologically unlikely event, and still be so common?,” for which he drew a“Guardian of Genetic Fidelity” as a watchtower commanding mutated cells to commit suicide. For “Why dowe have fingerprints?,” Nora Krug’s comic rationale depicts a thief using his finger*tips for “climbing support” and “texture detection.” Others are playfully decorative, like Roman Klonek’s answer to “Why is each snowflake unique?” And a few seem to be understandably flummoxed by the questions, like Atak’s art brut rendering of “Why do we age?”

Contrary to the cover image, an unexplained biological cross section, this book is not about medical illustration. If you’re looking for fun facts illustrated by some amusing imagery, it does the job well.

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/10/21/bo...gewanted=print