By CORNELIA DEAN

TO FORGIVE DESIGN:

Understanding Failure

By Henry Petroski

410 pages.

The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. $27.95.

In May 1987 the Golden Gate Bridge had a 50th birthday party. The bridge was closed to automobile traffic so people could enjoy a walk across the spectacular span.

Organizers expected perhaps 50,000 pedestrians to show up. Instead, by some estimates, as many as 800,000 thronged the bridge approaches. By the time 250,000 were on the bridge engineers noticed something ominous: the roadway was flattening under what turned out to be the heaviest load it had ever been asked to carry. Worse, it was beginning to sway.

“Though crowds of people do not generally walk in step, if the bridge beneath them begins to move sideways — for whatever reason — the people on it instinctively tend to fall into step the better to keep their balance,” Henry Petroski writes. “This in turn exacerbates the sideways motion of the structure, and a positive feedback loop is developed,” making matters worse and worse.

This time disaster was averted. The authorities closed access to the bridge and tens of thousands of people, caught in pedestrian gridlock, made their way back to land, a process that for some took hours.

The story is one of scores in “To Forgive Design: Understanding Failure,” a book that is at once an absorbing love letter to engineering and a paean to its breakdowns.

Disaster has long been grist for Dr. Petroski. His first book, in 1985, was “To Engineer Is Human: The Role of Failure in Successful Design.” Since then he has written widely on failure, in other books and in a regular column in the magazine American Scientist. He has also produced book-length discussions of design successes, like the pencil (point breakage notwithstanding) and the toothpick.

Like all of us, engineers hope their designs will succeed, solving old problems in new ways or making things faster, cheaper, more efficient or more pleasant. But, as Dr. Petroski writes, “no matter what the technology is, our best estimates of its success tend to be overly optimistic.”

Failure is what drives the field forward.

“There is nothing new about things breaking,” Dr. Petroski writes, be they teeth subjected to the “cycles of stress” we call chewing, cardiac stents exposed to the corrosive effects of — who knew? — human blood or large stone obelisks suddenly coming apart, which he tells us motivated Galileo’s research into the strength of materials.

This book is a litany of failure, including falling concrete in the Big Dig in Boston, the loss of the space shuttles Challenger and Columbia, the rupture of New Orleans levees, collapsing buildings in the Haitian earthquake, the Deepwater Horizon blowout, the sinking of the Titanic, the metal fatigue that doomed 1950s-era de Havilland Comet jets — and swaying, crumpling bridges from Britain to Cambodia.

Though he acknowledges that engineering works can fail because the person who thought them up or engineered them simply got things wrong, in this book Dr. Petroski widens his view to consider the larger arena in which such failures occur.

Sometimes devices fail because they are subjected to unexpected stress, like the Golden Gate under the weight of all those people, who collectively applied far more stress than the ordinary automobile traffic the bridge was supposed to carry.

Then there are the insulating O rings on the booster that launched the Challenger, which stiffened on an unusually cold morning in Cape Canaveral, Fla. Engineers alarmed by this issue recommended that the launch be postponed; managers overruled them.

Perhaps a good design is constructed with shoddy materials incompetently applied, factors Dr. Petroski says were at play in the concrete woes of Haiti’s housing stock after its 2010 earthquake.

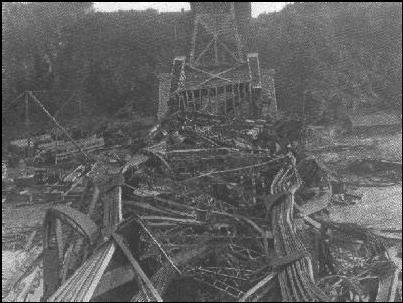

Or perhaps a design works so well it is adopted elsewhere again and again, with incremental, seemingly innocuous improvements, until, suddenly, it does not work at all anymore. That was the case in one of the most notorious engineering failures, the collapse of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge, in Washington State in 1940.

Its design was not that different from the design of other successful bridges. But people wanted an elegant structure, so they built it narrow, just two lanes wide. Shortly after it opened, in winds of only about 40 miles per hour, it began to sway, eventually contorting itself until it collapsed.

In a way, failure has shaped Dr. Petroski’s career. As a young engineer at Argonne National Laboratory he worked on the fracture mechanics of nuclear-reactor vessels. But when job prospects dried up after the accident at Three Mile Island, he took a job at Duke University, where today he is a professor of civil engineering.

Readers of his earlier books will encounter stories they have heard before in “To Forgive Design.” But they will encounter new stories, too, and a moving discussion of the responsibility of the engineer to the public and the ways young engineers can be helped to grasp them.

After the 1907 collapse of a bridge under construction in Quebec, engineers in Canada instituted a ceremony by which new graduates entering the profession received iron rings meant to remind them of their responsibilities. A variation of this practice is spreading in the United States, even as this country struggles to enhance its engineering success in the world economy.

People who study the ecology of innovation say one of our biggest advantages may be our willingness to accept failure, however distressing, as an inevitable byproduct of ambition. In the United States, if some unanticipated factor causes your good idea to fail, relatively little stigma attaches to you. In fact, you will hear people in Silicon Valley say that if you have not gone bankrupt at least once or twice, you’re not trying hard enough.

“Success is success but that is all that it is,” Dr. Petroski writes. It is failure that brings improvement.

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/13/bo....html?_r=1&hpw

An Artist and Inventor Whose Medium Was Sound

By STEPHEN HOLDEN

“Deconstructing Dad: The Music, Machines and Mystery of Raymond Scott” is Stan Warnow’s heartfelt documentary about the life and legacy of his emotionally remote father, an eccentric techno-music pioneer. In Scott’s single-minded pursuit of an offbeat musical vision, he has been compared to Frank Zappa; one talking head describes him as “an audio version of Andy Warhol.” Like “My Architect,” Nathaniel Kahn’s film about his father, Louis I. Kahn, this documentary is a son’s attempt to forge a posthumous bond with an elusive parent.

Scott, who died in 1994, belonged to that breed of obsessed genius-inventors who focus so intensely on their work that fame and riches are almost incidental. Shy and secretive, he preferred to remain in the background even after achieving some renown. When shown in front of the camera, he is visibly uncomfortable.

Born in Brooklyn in 1908 (he legally changed his name from Harry Warnow), Scott enjoyed hits in the late 1930s as the leader, composer and arranger of the Raymond Scott Quintette, a progressive swing ensemble whose peppy, hyper-agitated instrumentals included “Twilight in Turkey” and “The Toy Trumpet.” The music sounded like jazz but wasn’t, because no element was left to chance.

After Scott’s catalog was bought in the 1940s by Warner Brothers under Carl Stalling, its musical director of cartoons, his music became ubiquitous in animated Bugs Bunny and Porky Pig films, especially the composition “Powerhouse,” which has even been used in “The Simpsons.” Stalling is credited in the film for keeping Scott’s music alive. Another unsung accomplishment was Scott’s creation of the first racially integrated radio orchestra as the musical director of CBS.

Musicians as diverse as the composer and conductor John Williams, whose father was a drummer in Quintette; Mark Mothersbaugh, a co-founder of Devo; and Paul D. Miller, a k a DJ Spooky, call Scott a significant influence on contemporary music. One talking head cites his early ’60s album “Soothing Sounds for Baby” as a precursor to the work of Brian Eno and Philip Glass.

In the 1950s Scott achieved some fame as the musical director of “Your Hit Parade,” but the job was a moneymaking sideline to his real passion, which was controlling and manipulating sound, a lifelong fascination with mechanized music that began in childhood with his discovery of the player piano.

His need for absolute control extended to people. Under his tutelage Dorothy Collins, a “Hit Parade” star whom he had groomed from the age of 12 when she joined the family as his live-in protégée, endured rigorous training. When they married in 1952, she became the second of his three wives. They divorced in 1965.

This well-made film argues that Scott’s most significant achievements were his inventions of electronic instruments like the Clavivox, an early synthesizer, and the Electronium, a machine for electronic composition that attracted the backing of the Motown founder Berry Gordy Jr., who eventually lost interest.

Scott’s fascination with the human-machine interface deepened as he aged. He envisioned the Electronium as a music machine (“Beethoven in a box”) that generated original compositions. His ultimate dream was the harnessing of brain waves so that music could be transmitted telepathically. As computer technology advances, that dream is not as crazy-sounding as it might have seemed even a few years ago.

Deconstructing Dad

The Music, Machines

and Mystery of Raymond Scott

Opens on Friday in Manhattan.

Produced, directed and edited by Stan Warnow; director of photography, Mr. Warnow; released by Cavu Pictures. At the Quad Cinema, 34 West 13th Street, Greenwich Village. Running time: 1 hour 38 minutes. This film is not rated.

http://movies.nytimes.com/2012/07/13...tml?ref=movies

TO FORGIVE DESIGN:

Understanding Failure

By Henry Petroski

410 pages.

The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. $27.95.

In May 1987 the Golden Gate Bridge had a 50th birthday party. The bridge was closed to automobile traffic so people could enjoy a walk across the spectacular span.

Organizers expected perhaps 50,000 pedestrians to show up. Instead, by some estimates, as many as 800,000 thronged the bridge approaches. By the time 250,000 were on the bridge engineers noticed something ominous: the roadway was flattening under what turned out to be the heaviest load it had ever been asked to carry. Worse, it was beginning to sway.

“Though crowds of people do not generally walk in step, if the bridge beneath them begins to move sideways — for whatever reason — the people on it instinctively tend to fall into step the better to keep their balance,” Henry Petroski writes. “This in turn exacerbates the sideways motion of the structure, and a positive feedback loop is developed,” making matters worse and worse.

This time disaster was averted. The authorities closed access to the bridge and tens of thousands of people, caught in pedestrian gridlock, made their way back to land, a process that for some took hours.

The story is one of scores in “To Forgive Design: Understanding Failure,” a book that is at once an absorbing love letter to engineering and a paean to its breakdowns.

Disaster has long been grist for Dr. Petroski. His first book, in 1985, was “To Engineer Is Human: The Role of Failure in Successful Design.” Since then he has written widely on failure, in other books and in a regular column in the magazine American Scientist. He has also produced book-length discussions of design successes, like the pencil (point breakage notwithstanding) and the toothpick.

Like all of us, engineers hope their designs will succeed, solving old problems in new ways or making things faster, cheaper, more efficient or more pleasant. But, as Dr. Petroski writes, “no matter what the technology is, our best estimates of its success tend to be overly optimistic.”

Failure is what drives the field forward.

“There is nothing new about things breaking,” Dr. Petroski writes, be they teeth subjected to the “cycles of stress” we call chewing, cardiac stents exposed to the corrosive effects of — who knew? — human blood or large stone obelisks suddenly coming apart, which he tells us motivated Galileo’s research into the strength of materials.

This book is a litany of failure, including falling concrete in the Big Dig in Boston, the loss of the space shuttles Challenger and Columbia, the rupture of New Orleans levees, collapsing buildings in the Haitian earthquake, the Deepwater Horizon blowout, the sinking of the Titanic, the metal fatigue that doomed 1950s-era de Havilland Comet jets — and swaying, crumpling bridges from Britain to Cambodia.

Though he acknowledges that engineering works can fail because the person who thought them up or engineered them simply got things wrong, in this book Dr. Petroski widens his view to consider the larger arena in which such failures occur.

Sometimes devices fail because they are subjected to unexpected stress, like the Golden Gate under the weight of all those people, who collectively applied far more stress than the ordinary automobile traffic the bridge was supposed to carry.

Then there are the insulating O rings on the booster that launched the Challenger, which stiffened on an unusually cold morning in Cape Canaveral, Fla. Engineers alarmed by this issue recommended that the launch be postponed; managers overruled them.

Perhaps a good design is constructed with shoddy materials incompetently applied, factors Dr. Petroski says were at play in the concrete woes of Haiti’s housing stock after its 2010 earthquake.

Or perhaps a design works so well it is adopted elsewhere again and again, with incremental, seemingly innocuous improvements, until, suddenly, it does not work at all anymore. That was the case in one of the most notorious engineering failures, the collapse of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge, in Washington State in 1940.

Its design was not that different from the design of other successful bridges. But people wanted an elegant structure, so they built it narrow, just two lanes wide. Shortly after it opened, in winds of only about 40 miles per hour, it began to sway, eventually contorting itself until it collapsed.

In a way, failure has shaped Dr. Petroski’s career. As a young engineer at Argonne National Laboratory he worked on the fracture mechanics of nuclear-reactor vessels. But when job prospects dried up after the accident at Three Mile Island, he took a job at Duke University, where today he is a professor of civil engineering.

Readers of his earlier books will encounter stories they have heard before in “To Forgive Design.” But they will encounter new stories, too, and a moving discussion of the responsibility of the engineer to the public and the ways young engineers can be helped to grasp them.

After the 1907 collapse of a bridge under construction in Quebec, engineers in Canada instituted a ceremony by which new graduates entering the profession received iron rings meant to remind them of their responsibilities. A variation of this practice is spreading in the United States, even as this country struggles to enhance its engineering success in the world economy.

People who study the ecology of innovation say one of our biggest advantages may be our willingness to accept failure, however distressing, as an inevitable byproduct of ambition. In the United States, if some unanticipated factor causes your good idea to fail, relatively little stigma attaches to you. In fact, you will hear people in Silicon Valley say that if you have not gone bankrupt at least once or twice, you’re not trying hard enough.

“Success is success but that is all that it is,” Dr. Petroski writes. It is failure that brings improvement.

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/13/bo....html?_r=1&hpw

An Artist and Inventor Whose Medium Was Sound

By STEPHEN HOLDEN

“Deconstructing Dad: The Music, Machines and Mystery of Raymond Scott” is Stan Warnow’s heartfelt documentary about the life and legacy of his emotionally remote father, an eccentric techno-music pioneer. In Scott’s single-minded pursuit of an offbeat musical vision, he has been compared to Frank Zappa; one talking head describes him as “an audio version of Andy Warhol.” Like “My Architect,” Nathaniel Kahn’s film about his father, Louis I. Kahn, this documentary is a son’s attempt to forge a posthumous bond with an elusive parent.

Scott, who died in 1994, belonged to that breed of obsessed genius-inventors who focus so intensely on their work that fame and riches are almost incidental. Shy and secretive, he preferred to remain in the background even after achieving some renown. When shown in front of the camera, he is visibly uncomfortable.

Born in Brooklyn in 1908 (he legally changed his name from Harry Warnow), Scott enjoyed hits in the late 1930s as the leader, composer and arranger of the Raymond Scott Quintette, a progressive swing ensemble whose peppy, hyper-agitated instrumentals included “Twilight in Turkey” and “The Toy Trumpet.” The music sounded like jazz but wasn’t, because no element was left to chance.

After Scott’s catalog was bought in the 1940s by Warner Brothers under Carl Stalling, its musical director of cartoons, his music became ubiquitous in animated Bugs Bunny and Porky Pig films, especially the composition “Powerhouse,” which has even been used in “The Simpsons.” Stalling is credited in the film for keeping Scott’s music alive. Another unsung accomplishment was Scott’s creation of the first racially integrated radio orchestra as the musical director of CBS.

Musicians as diverse as the composer and conductor John Williams, whose father was a drummer in Quintette; Mark Mothersbaugh, a co-founder of Devo; and Paul D. Miller, a k a DJ Spooky, call Scott a significant influence on contemporary music. One talking head cites his early ’60s album “Soothing Sounds for Baby” as a precursor to the work of Brian Eno and Philip Glass.

In the 1950s Scott achieved some fame as the musical director of “Your Hit Parade,” but the job was a moneymaking sideline to his real passion, which was controlling and manipulating sound, a lifelong fascination with mechanized music that began in childhood with his discovery of the player piano.

His need for absolute control extended to people. Under his tutelage Dorothy Collins, a “Hit Parade” star whom he had groomed from the age of 12 when she joined the family as his live-in protégée, endured rigorous training. When they married in 1952, she became the second of his three wives. They divorced in 1965.

This well-made film argues that Scott’s most significant achievements were his inventions of electronic instruments like the Clavivox, an early synthesizer, and the Electronium, a machine for electronic composition that attracted the backing of the Motown founder Berry Gordy Jr., who eventually lost interest.

Scott’s fascination with the human-machine interface deepened as he aged. He envisioned the Electronium as a music machine (“Beethoven in a box”) that generated original compositions. His ultimate dream was the harnessing of brain waves so that music could be transmitted telepathically. As computer technology advances, that dream is not as crazy-sounding as it might have seemed even a few years ago.

Deconstructing Dad

The Music, Machines

and Mystery of Raymond Scott

Opens on Friday in Manhattan.

Produced, directed and edited by Stan Warnow; director of photography, Mr. Warnow; released by Cavu Pictures. At the Quad Cinema, 34 West 13th Street, Greenwich Village. Running time: 1 hour 38 minutes. This film is not rated.

http://movies.nytimes.com/2012/07/13...tml?ref=movies

Comment