Interesting history plus a very early example of public/private...

http://exiledonline.com/golden-state...-and-counting/

http://exiledonline.com/golden-state...-and-counting/

I was going through some of my Victorville notes and came across an amazing, untold story that I never had the chance to write up. It is about California’s Miller family, an aristocratic clan that’s been extracting rent from California taxpayers for the past 150 years, ever since their patriarch started looting land back in the 19th century.

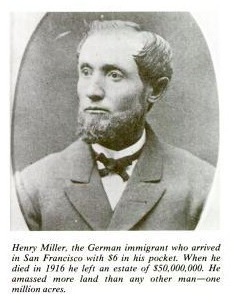

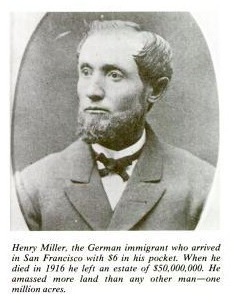

It all began with Henry Miller, the “Cattle King of California,” who once had the honor of being the largest landowner in the United States. The man had so much land that he liked to brag about being able to drive his cattle from Los Angeles to San Francisco without ever leaving his own property.

“Henry Miller left behind him the largest area of land under a single ownership ever assembled in America, probably the world, if private individual ownership and now the feudal domains of Kings is alone considered. … Eight hundred thousand acres in California—more than 1,250 square miles—nearly as much in Oregon and half as much in Nevada, constituting the entire holdings of Miller & Lux, Inc,” gushed the New York Times in a 1921 profile of Miller’s disintegrating empire, 5 years after his death.

The man had amassed his incredible land fortune in pre-railroad days, supplying the hungry Gold Rush crowd with all-natural grass-fed beef in exchange for their gold nuggets. But the Cattle King was wiped out by railroad technology, which allowed the powerful Chicago Meat Trust to deliver their shitty industrial-farm-raised beef directly to the San Francisco market in refrigerated railroad cars.

It’s been about a hundred years since his empire crumbled, but his family retained a good chunk of his vast land wealth, including perpetual rights to a massive amount of water. A good part of the Miller clan is now sitting pretty just by exploiting and selling their hereditary water rights on the California water market for millions of dollars a year. In fact, it’s safe to say that the family has successfully leveraged grandpa Miller’s vast real estate and agricultural holdings into creating one of California’s largest water merchant businesses, which sells water at exorbitant rates to cities, counties, real estate developers, farmers and even the state itself.

It’s hard to compete with this privileged class. People like us have to pay for our water, but the Millers get theirs free—for eternity.

Portrait of a Scammer as a Young Man

He stands out now, but Henry Miller was probably a boringly typical greed head when he was coming up, one of thousands who swarmed California during the Gold Rush to scam their way to prosperity.

The son of a German butcher, he ran away from home as a teenager and made his way to California in the mid-1800s. He changed his name en route, opened up a butcher shop with a partner, married into elite society, and started leveraging his profits and connections into buying as much real estate as he possibly could, always on the lookout for land with water rights and access to rivers and streams. The man was obsessed with growing his business operation, and supposedly took pleasure in nothing but work, not even in food. “I’d stop eating if I could,” he once wrote a friend.

“Even after he had become a multimillionaire, he always insisted on having his potatoes boiled in the jackets because the skins could be peeled thinner that way, and he would go into a rage if he were given a full cup of coffee after he had asked for only a half cup, because this meant he was going to have to drink more than he thought was good for him in order to avoid the wastefulness of throwing any coffee out,” according to a 1967 profile in the American Heritage Magazine.

Miller was nickel-and-diming his way to prosperity, and clearly knew what he was doing.

Carey McWilliams, in his book Factories in the Field, was in total awe of Miller’s business abilities, writing “His career is almost without parallel in the history of land monopolization in America. He must be considered as a member of the great brotherhood of buccaneers: the Goulds, the Harrimans, the Astors, the Vanderbilts.” Marc Reisnser, in Cadillac Desert, likewise shows respect for the man, lovingly referring to Henry Miller as a “mythical figure in the history of California land fraud.”

Miller scammed the federal government for land and ruthlessly used corrupt state courts to steal land from owners of Mexican land grants. One of his crowning achievements was when, with the help of the notoriously corrupt lawyer and future California governor Harry Haight (after whom Haight Street was named), Miller and Lux litigated a Mexican-American landowning family into insolvency and forced them to sell a property called Buri Buri Ranch, which stretched from the southern tip of San Francisco all the way down to Burlingame, spanning some of the best property in the Bay Area. Snatching Buri Buri was all about securing grazing land for his massive cow herds as close to the San Francisco meat market as humanly possible. Remember, they didn’t have refrigerators back then. Once you kill it, you better eat it–and quick, too.

But more than anything, Miller is remembered today for his impact on California’s water economy. Before everybody else, Miller realized that water would become the state’s most valuable and strategic resource. Early on, he and his business partners acquired land on both sides of major California rivers, allowing him to monopolize and control the agricultural water supply. Miller had over 100 miles of the San Joaquin River, one of the largest in the state, sewed up tight. He also controlled 50 miles of Kern River frontage.

According to Reisner, Miller got a lot of that real estate for free by filing false land claims via the Swamplands Act:

After his death in 1916, Henry Miller’s empire passed to his spoiled children, who quarreled over and squandered their inheritance for two generations, until Miller’s spirit was reincarnated in his great grandson, George Nickel Jr.

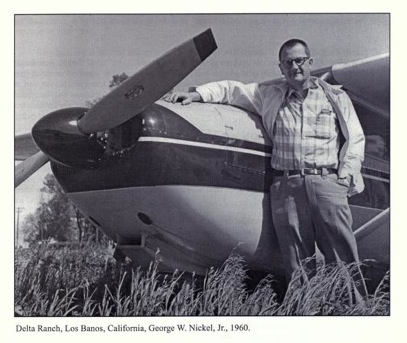

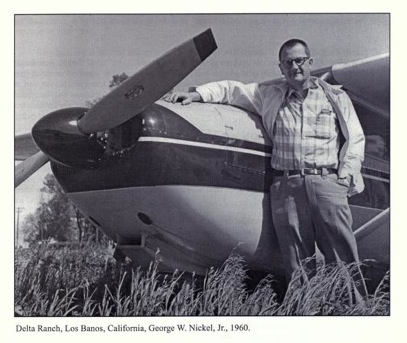

George Nickel, who grew up in Burlingame and went to UC Berkeley, was born to the daughter of one of the “original pioneering families” of San Francisco that was a big time international grain trader with its own fleet of ships, and the son of one of Henry Miller’s three daughters. You could say George was set up pretty nice.

He didn’t have to go in his great grandfather’s footsteps. He could have easily become a softdrink executive at Coca-Cola or a playboy like his father (who lost interest in the ranching lifestyle after he was shot by a disgruntled employee), but in the end he decided to live up to Miller legacy.

Gaining control over part of the Miller empire in 1964, Nickel focused on land and water development in the Central Valley. While Henry Miller had toiled to secure land and water rights for his cattle ranching business, Nickel saw a way to exploit them to fuel California’s real estate market.

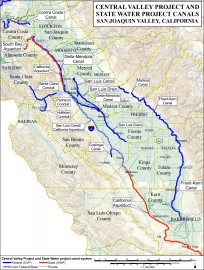

As luck would have it, just as Nickel started getting involved in the family business, Governor Pat Brown was elected and started pushing through with his plan to build the California Aqueduct. This massive concrete river would span over 700 miles—from the southern edge of the San Francisco Bay down to Southern California—and go right through the Nickel family’s land holdings.

Like Nickel, Governor Brown came from an old San Francisco family that’s been in the state since the mid-1800s. Naturally, Nickel did all he could to help a brother out:

But the money Nickel made helping out the state was just the beginning.

Now that he was plugged into California Aqueduct, Nickel started experimenting with “water banking”—which involves diverting water from a river into an underground aquifer during wet periods and storing it there for later use. The aqueduct system was thus used to move water around the state, selling it to other farmers, cities and real estate developments in the most arid reaches of the Central Valley and beyond. This practice marked the start of a fundamental transformation in California’s water economy, allowing water to be bought, sold, and traded on the open market as any other commodity.

“My father was marketing waterway before anybody else, before it was cool,” said Jim Nickel, who’s been running the Nickel family business since his dad died in 2004.

Water sales information is hard to come by, so it’s not clear exactly how much the Nickels have made over the years selling grandpa Henry’s water to California residents. But you can rest assured it is a helluva lot.

Here’s a recent example: In 2001, just before George Nickel finally kicked the bucket, the old man used his hereditary water rights to pull off one final scam that would keep his kids flush with cash for years to come.

The Sacramento Bee explained it in 2002:

The best part? No matter how much money the Nickels make selling this water allotment, California is obligated to deliver it at taxpayers’ expense. That’s right. California residents incur all the costs, the Nickels take home all the profits. That’s how California’s nobility likes—and expects—to be treated in its home state.

When he wasn’t working, Nickel spend his life playing the part of a true nobleman: He vacationed at a JP Morgan family mansion in Lake Tahoe, built an elite tennis club in Bakersfield, flew around California on helicopters, and scammed federal agencies for subsidized loans. He also took pleasure in chasing peasants off public property that he felt rightfully belonged to him, going as far as trying to prevent rafters and kayakers from cruising down a portion of the Kern River that runs in front of his house through his property, by erecting barbed wire fences and ordering his private security guards to arrest anyone they could catch.

George Nickel is dead, but his sons are carrying on as best they can.

Jim Nickel runs the family’s agricultural and water operations, while Jamie Nickel serves at the director of Federal Crop Insurance Corporation at USDA and manages the real estate end of the business. Meanwhile his grandson, George W. Nickel, III, is is a budding politician in California, who unsuccessfully ran for the state senate and now works in the Obama administration. Oh, and on top of everything, the family gets a nice revenue stream from the federal government, pulling in roughly $3.6 million in farm subsidies since 1996.

A lot of people say the solution to California’s chronic water shortage is privatization, because it allows for a more efficient allocation of water resources. They’re right. Just think: by, say, 2150 we could achieve maximum efficiency by forcing Californians to buy all their water from Nickel offspring.

It all began with Henry Miller, the “Cattle King of California,” who once had the honor of being the largest landowner in the United States. The man had so much land that he liked to brag about being able to drive his cattle from Los Angeles to San Francisco without ever leaving his own property.

“Henry Miller left behind him the largest area of land under a single ownership ever assembled in America, probably the world, if private individual ownership and now the feudal domains of Kings is alone considered. … Eight hundred thousand acres in California—more than 1,250 square miles—nearly as much in Oregon and half as much in Nevada, constituting the entire holdings of Miller & Lux, Inc,” gushed the New York Times in a 1921 profile of Miller’s disintegrating empire, 5 years after his death.

The man had amassed his incredible land fortune in pre-railroad days, supplying the hungry Gold Rush crowd with all-natural grass-fed beef in exchange for their gold nuggets. But the Cattle King was wiped out by railroad technology, which allowed the powerful Chicago Meat Trust to deliver their shitty industrial-farm-raised beef directly to the San Francisco market in refrigerated railroad cars.

It’s been about a hundred years since his empire crumbled, but his family retained a good chunk of his vast land wealth, including perpetual rights to a massive amount of water. A good part of the Miller clan is now sitting pretty just by exploiting and selling their hereditary water rights on the California water market for millions of dollars a year. In fact, it’s safe to say that the family has successfully leveraged grandpa Miller’s vast real estate and agricultural holdings into creating one of California’s largest water merchant businesses, which sells water at exorbitant rates to cities, counties, real estate developers, farmers and even the state itself.

It’s hard to compete with this privileged class. People like us have to pay for our water, but the Millers get theirs free—for eternity.

Portrait of a Scammer as a Young Man

He stands out now, but Henry Miller was probably a boringly typical greed head when he was coming up, one of thousands who swarmed California during the Gold Rush to scam their way to prosperity.

The son of a German butcher, he ran away from home as a teenager and made his way to California in the mid-1800s. He changed his name en route, opened up a butcher shop with a partner, married into elite society, and started leveraging his profits and connections into buying as much real estate as he possibly could, always on the lookout for land with water rights and access to rivers and streams. The man was obsessed with growing his business operation, and supposedly took pleasure in nothing but work, not even in food. “I’d stop eating if I could,” he once wrote a friend.

“Even after he had become a multimillionaire, he always insisted on having his potatoes boiled in the jackets because the skins could be peeled thinner that way, and he would go into a rage if he were given a full cup of coffee after he had asked for only a half cup, because this meant he was going to have to drink more than he thought was good for him in order to avoid the wastefulness of throwing any coffee out,” according to a 1967 profile in the American Heritage Magazine.

Miller was nickel-and-diming his way to prosperity, and clearly knew what he was doing.

Carey McWilliams, in his book Factories in the Field, was in total awe of Miller’s business abilities, writing “His career is almost without parallel in the history of land monopolization in America. He must be considered as a member of the great brotherhood of buccaneers: the Goulds, the Harrimans, the Astors, the Vanderbilts.” Marc Reisnser, in Cadillac Desert, likewise shows respect for the man, lovingly referring to Henry Miller as a “mythical figure in the history of California land fraud.”

Miller scammed the federal government for land and ruthlessly used corrupt state courts to steal land from owners of Mexican land grants. One of his crowning achievements was when, with the help of the notoriously corrupt lawyer and future California governor Harry Haight (after whom Haight Street was named), Miller and Lux litigated a Mexican-American landowning family into insolvency and forced them to sell a property called Buri Buri Ranch, which stretched from the southern tip of San Francisco all the way down to Burlingame, spanning some of the best property in the Bay Area. Snatching Buri Buri was all about securing grazing land for his massive cow herds as close to the San Francisco meat market as humanly possible. Remember, they didn’t have refrigerators back then. Once you kill it, you better eat it–and quick, too.

But more than anything, Miller is remembered today for his impact on California’s water economy. Before everybody else, Miller realized that water would become the state’s most valuable and strategic resource. Early on, he and his business partners acquired land on both sides of major California rivers, allowing him to monopolize and control the agricultural water supply. Miller had over 100 miles of the San Joaquin River, one of the largest in the state, sewed up tight. He also controlled 50 miles of Kern River frontage.

According to Reisner, Miller got a lot of that real estate for free by filing false land claims via the Swamplands Act:

If there was federal land that overflowed enough so that you could traverse it at times in a flat-bottomed boat, and you promised to reclaim it (which is to say, dike and drain it), it was yours. Henry Miller … acquired a large part of his 1,090,000-acre empire under this act. According to legend, he bought himself a boat, hired some witnesses, put the boat and witnesses over county-size tracts near the San Joaquin River where it rains, on the average, about eight or nine inches a year. The land became his. The sanitized version of the story, the one told by Miller’s descendants, has him benefiting more from luck than from ruse. During the winter of 1861 and 1862, most of California got three times its normal precipitation, and the usually semiarid Central Valley became a shallow sea the size of Lake Ontario. But the only difference in this version is that Miller didn’t need a wagon for his boat; he still had no business acquiring hundreds of thousands of acres of the public domain, yet he managed it with ease.

That foresight and fraud still sustains the Miller clan, which has continued to find new ways in which it could exploit grandpa Henry’s plunder.After his death in 1916, Henry Miller’s empire passed to his spoiled children, who quarreled over and squandered their inheritance for two generations, until Miller’s spirit was reincarnated in his great grandson, George Nickel Jr.

George Nickel, who grew up in Burlingame and went to UC Berkeley, was born to the daughter of one of the “original pioneering families” of San Francisco that was a big time international grain trader with its own fleet of ships, and the son of one of Henry Miller’s three daughters. You could say George was set up pretty nice.

He didn’t have to go in his great grandfather’s footsteps. He could have easily become a softdrink executive at Coca-Cola or a playboy like his father (who lost interest in the ranching lifestyle after he was shot by a disgruntled employee), but in the end he decided to live up to Miller legacy.

Gaining control over part of the Miller empire in 1964, Nickel focused on land and water development in the Central Valley. While Henry Miller had toiled to secure land and water rights for his cattle ranching business, Nickel saw a way to exploit them to fuel California’s real estate market.

Rancher George Nickel hugs his winged stallion

As luck would have it, just as Nickel started getting involved in the family business, Governor Pat Brown was elected and started pushing through with his plan to build the California Aqueduct. This massive concrete river would span over 700 miles—from the southern edge of the San Francisco Bay down to Southern California—and go right through the Nickel family’s land holdings.

See that red and line running down the middle? That’s our gift to California’s nobility

Like Nickel, Governor Brown came from an old San Francisco family that’s been in the state since the mid-1800s. Naturally, Nickel did all he could to help a brother out:

The state was building the California Aqueduct in the early 1960s and needed a water supply in Kern for construction purposes.

Miller’s great-grandson George Nickel Jr. obliged by piping in water from a nearby ranch.

After the aqueduct was done, the state repaid him with three times as much water. He banked it in an aquifer and years later sold it to Chevron and Union Oil for drilling.

Totalling $8 million, these were among the first farm water sales, said Gene McMurtrey, a Bakersfield lawyer and historian.

What are old friends for, right?Miller’s great-grandson George Nickel Jr. obliged by piping in water from a nearby ranch.

After the aqueduct was done, the state repaid him with three times as much water. He banked it in an aquifer and years later sold it to Chevron and Union Oil for drilling.

Totalling $8 million, these were among the first farm water sales, said Gene McMurtrey, a Bakersfield lawyer and historian.

But the money Nickel made helping out the state was just the beginning.

Now that he was plugged into California Aqueduct, Nickel started experimenting with “water banking”—which involves diverting water from a river into an underground aquifer during wet periods and storing it there for later use. The aqueduct system was thus used to move water around the state, selling it to other farmers, cities and real estate developments in the most arid reaches of the Central Valley and beyond. This practice marked the start of a fundamental transformation in California’s water economy, allowing water to be bought, sold, and traded on the open market as any other commodity.

“My father was marketing waterway before anybody else, before it was cool,” said Jim Nickel, who’s been running the Nickel family business since his dad died in 2004.

Water sales information is hard to come by, so it’s not clear exactly how much the Nickels have made over the years selling grandpa Henry’s water to California residents. But you can rest assured it is a helluva lot.

Here’s a recent example: In 2001, just before George Nickel finally kicked the bucket, the old man used his hereditary water rights to pull off one final scam that would keep his kids flush with cash for years to come.

The Sacramento Bee explained it in 2002:

He was known as the cattle king of California, a legendary speculator who became the largest private landowner in the United States more than a century ago.

But Henry Miller was one of California’s original water barons as well, and today his descendants are wheeling and dealing in water with style and gusto. Just last year they pulled off a trade that brought them millions of dollars’ worth of water on the California Aqueduct — the state’s main waterway and an ideal trading post.

“We consider ourselves farmers,” said Miller descendant Jim Nickel, who runs a 10,000-acre ranch east of Bakersfield. “But we have to admit the water marketing has become a bigger part of our balance sheet than it used to be. It’s significant now.”

…

Last year Jim Nickel swapped some family water with the county Water Agency for $10 million and some water on the California Aqueduct. He got less water than he had, but the location was worth it. A few months later he sold every drop of the year’s allotment to the state’s environmental account for an eye-popping $460 an acre-foot, or $4.6 million.

More deals are coming. “I believe the real money is in long-term contracts,” Nickel said.

Not only did this deal hand the Nickels 10,000 acre-feet of water a year in perpetuity, it gave the family license to sell the water to anyone or any place along the 700-mile stretch of the California Aqueduct. This amount is enough to hydrate a city of 100,000 people, and could easily fetch $8 million a year.But Henry Miller was one of California’s original water barons as well, and today his descendants are wheeling and dealing in water with style and gusto. Just last year they pulled off a trade that brought them millions of dollars’ worth of water on the California Aqueduct — the state’s main waterway and an ideal trading post.

“We consider ourselves farmers,” said Miller descendant Jim Nickel, who runs a 10,000-acre ranch east of Bakersfield. “But we have to admit the water marketing has become a bigger part of our balance sheet than it used to be. It’s significant now.”

…

Last year Jim Nickel swapped some family water with the county Water Agency for $10 million and some water on the California Aqueduct. He got less water than he had, but the location was worth it. A few months later he sold every drop of the year’s allotment to the state’s environmental account for an eye-popping $460 an acre-foot, or $4.6 million.

More deals are coming. “I believe the real money is in long-term contracts,” Nickel said.

The best part? No matter how much money the Nickels make selling this water allotment, California is obligated to deliver it at taxpayers’ expense. That’s right. California residents incur all the costs, the Nickels take home all the profits. That’s how California’s nobility likes—and expects—to be treated in its home state.

When he wasn’t working, Nickel spend his life playing the part of a true nobleman: He vacationed at a JP Morgan family mansion in Lake Tahoe, built an elite tennis club in Bakersfield, flew around California on helicopters, and scammed federal agencies for subsidized loans. He also took pleasure in chasing peasants off public property that he felt rightfully belonged to him, going as far as trying to prevent rafters and kayakers from cruising down a portion of the Kern River that runs in front of his house through his property, by erecting barbed wire fences and ordering his private security guards to arrest anyone they could catch.

George Nickel is dead, but his sons are carrying on as best they can.

Jim Nickel runs the family’s agricultural and water operations, while Jamie Nickel serves at the director of Federal Crop Insurance Corporation at USDA and manages the real estate end of the business. Meanwhile his grandson, George W. Nickel, III, is is a budding politician in California, who unsuccessfully ran for the state senate and now works in the Obama administration. Oh, and on top of everything, the family gets a nice revenue stream from the federal government, pulling in roughly $3.6 million in farm subsidies since 1996.

A lot of people say the solution to California’s chronic water shortage is privatization, because it allows for a more efficient allocation of water resources. They’re right. Just think: by, say, 2150 we could achieve maximum efficiency by forcing Californians to buy all their water from Nickel offspring.

Comment