Three Billion Dead: The Future of Biofuels and the Future of Resistance by Sharon Astyk

This is a serious discussion topic, coupled with two other pieces

The Failure of Networked Systems

and

Peak Oil and the Financial Markets: A Forecast for 2008

I'm going to be asking all of you to do some hard work today - this is not going to be a short post, or an easy one, particularly if you read the referenced piece and the hundred or more relevant comments. We all have limited time and energy, and I'm not necessarily famous for my brevity, so I understand if this looks overwhelming to you, but I'd like people to try and get through it, because this is damned important.

The one time I saw Stuart Staniford speak, at ASPO Boston in the fall of 2006, he ended his analysis of oil peak data with something along the lines of "Peak Oil isn't the end of the world, folks." I'd tend to guess he may actually have changed his mind on this one. He's a guy who tends to be conservative in his estimates, and, as far as I can tell (I don't know him at all) someone who doesn't believe things until he's figured them out to his satisfaction. Since he's a brilliant data analyst, to his satisfaction is quite a high standard. But becuase he's not someone who leaps to conclusions, I tend to trust Staniford's thinking. That is, when he gets worried, I worry. When he says, as he does here, that he was "floored" - I sit up and pay attention. And in fact, I was too.

This is a very long, difficult and important piece, on the impact of biofuels on the food supply, world hunger and the future. I've been arguing intuitively from the perspective of someone whose interest is not in data analysis, that peak oil's first and deepest effects will appear in world hunger, but Staniford has pushed it further. http://www.theoildrum.com/node/2431. I strongly urge you to read the whole thing when you can, but his conclusion is this:

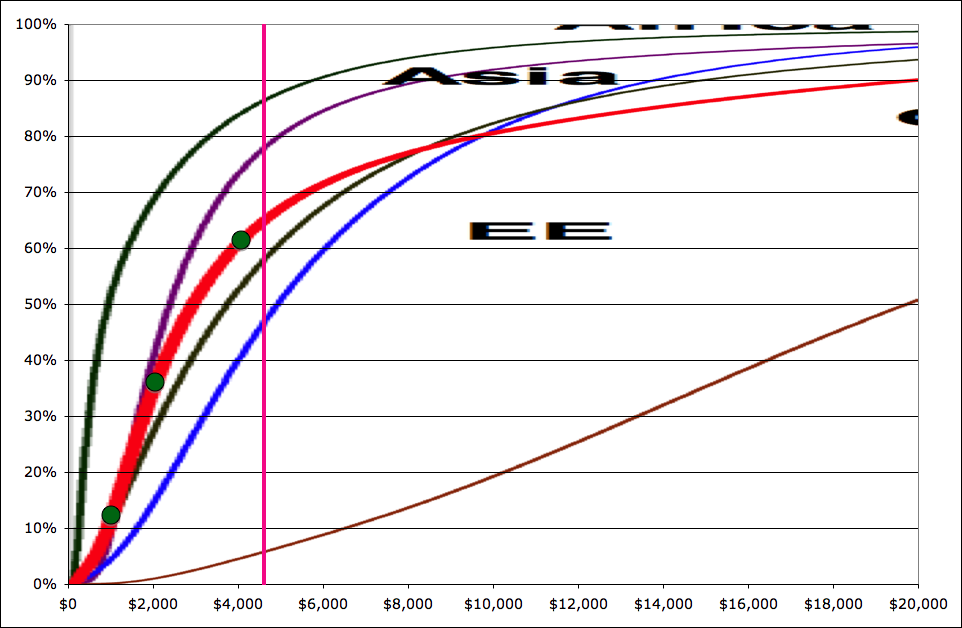

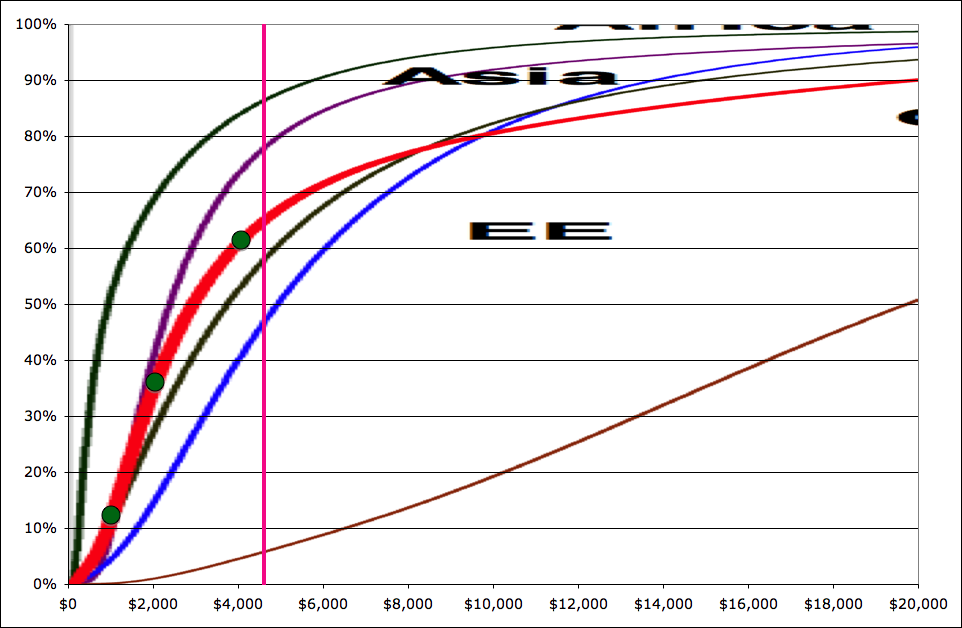

Here the value for the lower-income 2/3 of the world's population is about +0.7. What this means is that a 10% reduction in income has about the same effect on food consumption as a 10% increase in food prices. This suggests that we can use the global income distribution (shown above) to roughly estimate the impact of a doubling or quadrupling of food prices. We noted earlier that according to the UN about 800 million people are unable to meet minimal dietary energy requirements. That is 12% of the world population. On the income distribution (one graph back), the 12% mark corresponds to $1020/year in income (shown as the lowermost green dot). By looking at the $2040 level (36% of the global population - second green dot up), and the $4080 level (61% of the global population - third green dot up), we can estimate that a doubling in food prices over 2000 levels might bring 30% or so of the global population below the level of minimal dietary energy requirements, and a quadrupling of food prices over 2000 levels might bring 60% or so of the global population into that situation.

These estimates should be regarded as quite uncertain. Still, it seems hard to make a case that food price increases will cause a cessation of biofuel profitability before a significant fraction of the global population is in serious trouble. The poor will not be able to bid up food prices by factors of two and four and keep eating. In contrast, the quadrupling of global oil prices, and tripling of US gasoline prices, over the last five years has had very minimal impact on driving behavior by the middle classes.

The core problem is that gasoline price elasticity in the US is about -0.05, versus the -0.7 price elasticity for food consumption by poor consumers. This makes clear who is going to win the bidding war for food versus biofuels in a free market.

.

.

.

The one time I saw Stuart Staniford speak, at ASPO Boston in the fall of 2006, he ended his analysis of oil peak data with something along the lines of "Peak Oil isn't the end of the world, folks." I'd tend to guess he may actually have changed his mind on this one. He's a guy who tends to be conservative in his estimates, and, as far as I can tell (I don't know him at all) someone who doesn't believe things until he's figured them out to his satisfaction. Since he's a brilliant data analyst, to his satisfaction is quite a high standard. But becuase he's not someone who leaps to conclusions, I tend to trust Staniford's thinking. That is, when he gets worried, I worry. When he says, as he does here, that he was "floored" - I sit up and pay attention. And in fact, I was too.

This is a very long, difficult and important piece, on the impact of biofuels on the food supply, world hunger and the future. I've been arguing intuitively from the perspective of someone whose interest is not in data analysis, that peak oil's first and deepest effects will appear in world hunger, but Staniford has pushed it further. http://www.theoildrum.com/node/2431. I strongly urge you to read the whole thing when you can, but his conclusion is this:

Here the value for the lower-income 2/3 of the world's population is about +0.7. What this means is that a 10% reduction in income has about the same effect on food consumption as a 10% increase in food prices. This suggests that we can use the global income distribution (shown above) to roughly estimate the impact of a doubling or quadrupling of food prices. We noted earlier that according to the UN about 800 million people are unable to meet minimal dietary energy requirements. That is 12% of the world population. On the income distribution (one graph back), the 12% mark corresponds to $1020/year in income (shown as the lowermost green dot). By looking at the $2040 level (36% of the global population - second green dot up), and the $4080 level (61% of the global population - third green dot up), we can estimate that a doubling in food prices over 2000 levels might bring 30% or so of the global population below the level of minimal dietary energy requirements, and a quadrupling of food prices over 2000 levels might bring 60% or so of the global population into that situation.

These estimates should be regarded as quite uncertain. Still, it seems hard to make a case that food price increases will cause a cessation of biofuel profitability before a significant fraction of the global population is in serious trouble. The poor will not be able to bid up food prices by factors of two and four and keep eating. In contrast, the quadrupling of global oil prices, and tripling of US gasoline prices, over the last five years has had very minimal impact on driving behavior by the middle classes.

The core problem is that gasoline price elasticity in the US is about -0.05, versus the -0.7 price elasticity for food consumption by poor consumers. This makes clear who is going to win the bidding war for food versus biofuels in a free market.

.

.

.

The Failure of Networked Systems

and

Peak Oil and the Financial Markets: A Forecast for 2008

At this time of year, we read many financial forecasts for the year ahead. Nearly all of these are written with the "filter" assumption of infinite growth. "Oil production problems are a temporary issue; after a short dip, the economy is likely to continue growing rapidly again. We may have a short recession, but we will soon be back to business as usual." Etc.

I think this filter is fundamentally in error, and leads to a mistaken impression with respect to where the world is headed. The world is changing in a very major way. Oil is in short supply, and this shortage is likely to get larger in the future. The pressure of short supply and rising prices adds a systematic bias that the financial community is not recognizing. This bias has as its basis the fact that it is becoming more and more difficult for both people and businesses to pay back loans, because of the rising costs of oil and food. This situation cannot be expected to go away. In fact, it is certain to get worse in years ahead, as oil supplies become tighter.

Besides the systematic bias, there is also a systemic risk, arising from the interconnectedness of all of the parts of the economy. This was well described in a post a few days ago called The Failure of Networked Systems. One of the issues in systemic risk relates to the financial system itself. If one party in the financial system fails, it increases the likelihood that other parties in the economic system will fail as well.

Another aspect of systemic risk is the close ties of the financial system to the rest of the economy. One example is the higher oil and food prices mentioned above that lead to a systematic bias toward higher defaults. Another is the fact that the lack of oil can be expected to impede economic growth, making the infinite growth model underlying the current economic system less sustainable, based on the economic model of Robert Ayres and Benjamin Warr. Another linkage is that of oil with ethanol. Higher oil prices leads to increased pressure to produce more ethanol, which further raises food prices, as demonstrated by Stuart Staniford in Fermenting the Food Supply.

I think this filter is fundamentally in error, and leads to a mistaken impression with respect to where the world is headed. The world is changing in a very major way. Oil is in short supply, and this shortage is likely to get larger in the future. The pressure of short supply and rising prices adds a systematic bias that the financial community is not recognizing. This bias has as its basis the fact that it is becoming more and more difficult for both people and businesses to pay back loans, because of the rising costs of oil and food. This situation cannot be expected to go away. In fact, it is certain to get worse in years ahead, as oil supplies become tighter.

Besides the systematic bias, there is also a systemic risk, arising from the interconnectedness of all of the parts of the economy. This was well described in a post a few days ago called The Failure of Networked Systems. One of the issues in systemic risk relates to the financial system itself. If one party in the financial system fails, it increases the likelihood that other parties in the economic system will fail as well.

Another aspect of systemic risk is the close ties of the financial system to the rest of the economy. One example is the higher oil and food prices mentioned above that lead to a systematic bias toward higher defaults. Another is the fact that the lack of oil can be expected to impede economic growth, making the infinite growth model underlying the current economic system less sustainable, based on the economic model of Robert Ayres and Benjamin Warr. Another linkage is that of oil with ethanol. Higher oil prices leads to increased pressure to produce more ethanol, which further raises food prices, as demonstrated by Stuart Staniford in Fermenting the Food Supply.

Comment