Productivity Slows, Factory Orders Drop

December 5, 2006 (AP)

Productivity Growth Slows Sharply While Factory Orders Plunge

Growth in worker productivity slowed sharply in the summer while wages and benefits rose at a rate that was far below a previous estimate, a development likely to ease inflation worries at the Federal Reserve.

Productivity edged up at an 0.2 percent annual rate in the July-September quarter, the Commerce Department said Tuesday. That was slightly better than the zero change reported a month ago.

Wages and benefits per unit of output increased at an annual rate of 2.3 percent in the third quarter, much slower than the 3.8 percent advance previously reported.

Analysts said this downward revision should ease fears at the Fed that wage pressures were threatening to send inflation sharply higher.

"Based on these numbers, the Fed can rest easy about the threat of inflation," said Nariman Behravesh, chief economist at Global Insight, a private forecasting firm. "The only debate now seems to be about when the Fed will cut" interest rates.

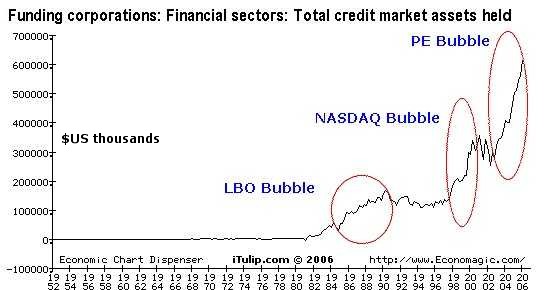

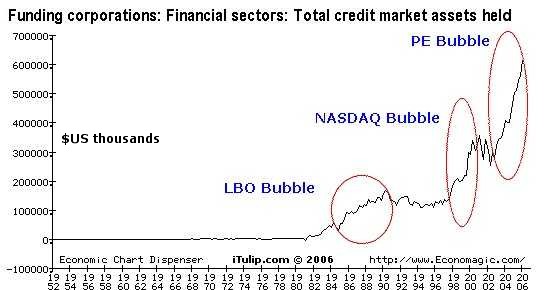

AntiSpin: The disconnect between U.S. and other nations' financial press reporting on the U.S. economy is reaching an extreme. Maybe "when the Fed will cut interest rates" is the only debate going on around Wall Street. Given the Dow's performance this quarter, that appears to be the case. But the rest of the planet is trying to figure out how the Fed can cut interest rates as the U.S. economy nears recession, with the dollar weak and weakening and private equity and hedge fund bubbles churning out LBOs to make the 1980s LBO and 1990 NASDAQ bubbles look like huts beside skyscrapers, with respect to debt leverage.

Can the Fed pour liquidity onto this or must Ben wait for it to collapse?

Dr. James Galbraith, whom we interviewed last week, weighs in today with the following piece in The Guardian.

One of the more intriguing comments to Galbraith's article comes from Thermopylae:

Long term, I'm not worried; it's the short term I'm concerned about. As Sir Winston Churchill said, America always does the right thing, but only after exhausting all other options.

The USA has a lot more bad options to exhaust before doing the right thing.

December 5, 2006 (AP)

Productivity Growth Slows Sharply While Factory Orders Plunge

Growth in worker productivity slowed sharply in the summer while wages and benefits rose at a rate that was far below a previous estimate, a development likely to ease inflation worries at the Federal Reserve.

Productivity edged up at an 0.2 percent annual rate in the July-September quarter, the Commerce Department said Tuesday. That was slightly better than the zero change reported a month ago.

Wages and benefits per unit of output increased at an annual rate of 2.3 percent in the third quarter, much slower than the 3.8 percent advance previously reported.

Analysts said this downward revision should ease fears at the Fed that wage pressures were threatening to send inflation sharply higher.

"Based on these numbers, the Fed can rest easy about the threat of inflation," said Nariman Behravesh, chief economist at Global Insight, a private forecasting firm. "The only debate now seems to be about when the Fed will cut" interest rates.

AntiSpin: The disconnect between U.S. and other nations' financial press reporting on the U.S. economy is reaching an extreme. Maybe "when the Fed will cut interest rates" is the only debate going on around Wall Street. Given the Dow's performance this quarter, that appears to be the case. But the rest of the planet is trying to figure out how the Fed can cut interest rates as the U.S. economy nears recession, with the dollar weak and weakening and private equity and hedge fund bubbles churning out LBOs to make the 1980s LBO and 1990 NASDAQ bubbles look like huts beside skyscrapers, with respect to debt leverage.

Can the Fed pour liquidity onto this or must Ben wait for it to collapse?

Dr. James Galbraith, whom we interviewed last week, weighs in today with the following piece in The Guardian.

The Dollar is Dying, Burnt in Iraq's Flames

Moreover: the world has lost confidence in America's elites

The demise of the dollar has clear links to the Iraq war and the world's loss of confidence in America's elites.

The melting away of the dollar is like global warming: you can't say that any one heat wave proves the trend, and there might be a cold snap next week. Still, over time, evidence builds up. And so, as the greenback approaches two to the pound, old-timers will remember the fall of sterling, under similar conditions of deficits and imperial retreat, a generation back. We have to ask: is the American financial empire on the brink? Let's take stock.

It's clear that Ben Bernanke got buffaloed, early on, by the tripe about his need to "establish credibility with the markets." There never was an inflation threat, apart from an oil-price bubble that popped last summer. Long-term interest rates would have reflected the threat if it existed, but they never did. So the Fed overshot, and raised rates too much. Now long rates are falling; Bernanke faces an inverting yield curve and even bank economists are starting to call his next move. That will be to start cutting rates, after a decent interval, sometime next year.

Once again, all you monetary policy buffs, in unison please:

The grand old Duke of York, he had ten thousand men.

He marched them up to the top of the hill. And marched them down again.

This is not good news for the dollar.

AntiSpin for Galbraith: Aren't long term rates more a function of The Three Desperados: Asian central banks, OPEC, and U.S. corporations than a reflection of inflation risks? Moreover: the world has lost confidence in America's elites

The demise of the dollar has clear links to the Iraq war and the world's loss of confidence in America's elites.

The melting away of the dollar is like global warming: you can't say that any one heat wave proves the trend, and there might be a cold snap next week. Still, over time, evidence builds up. And so, as the greenback approaches two to the pound, old-timers will remember the fall of sterling, under similar conditions of deficits and imperial retreat, a generation back. We have to ask: is the American financial empire on the brink? Let's take stock.

It's clear that Ben Bernanke got buffaloed, early on, by the tripe about his need to "establish credibility with the markets." There never was an inflation threat, apart from an oil-price bubble that popped last summer. Long-term interest rates would have reflected the threat if it existed, but they never did. So the Fed overshot, and raised rates too much. Now long rates are falling; Bernanke faces an inverting yield curve and even bank economists are starting to call his next move. That will be to start cutting rates, after a decent interval, sometime next year.

Once again, all you monetary policy buffs, in unison please:

The grand old Duke of York, he had ten thousand men.

He marched them up to the top of the hill. And marched them down again.

This is not good news for the dollar.

One of the more intriguing comments to Galbraith's article comes from Thermopylae:

It is, in part, precisely because the Pax Americana is strong that investors are bidding up currencies other than the dollar. Historically, the dollar has been a safe haven in times of uncertainty. Its safe haven status is not required today, for the simple reason that the American peace is profoundly stable.

For example, the dollar strengthened against the euro for three months after 9/11. Once it became clear that America had capable wartime leadership, it has been weakening ever since. Sophisticated international investors understand that the removal of the Taliban and the dismembering of the former Iraq are all requirements for the continued health of the Pax.

With a healthy Pax, there is no reason to be obsessive about investing in the dollar. One of the distinctive features of the American centuries is globalization; it would be odd in an era of globalization for so much of the world's reserves to be held in just one currency.

Thus Pax today means globalization, and globalization means a lower dollar. But the rub, of course, is that a lower dollar means a diminution of American power and, ultimately of its Pax.

The argument appears to be that the U.S. dollar is weak because the U.S. centric Pax global economic system appears to be strong. I don't buy it. America's trading partners have spent over 30 years trying to get into bed with America and, finding him less than expected (he's aged a bit, not quite as frisky as some Asian nations today, never mind that they are even less well educated) are now trying to figure out how to get back out again.For example, the dollar strengthened against the euro for three months after 9/11. Once it became clear that America had capable wartime leadership, it has been weakening ever since. Sophisticated international investors understand that the removal of the Taliban and the dismembering of the former Iraq are all requirements for the continued health of the Pax.

With a healthy Pax, there is no reason to be obsessive about investing in the dollar. One of the distinctive features of the American centuries is globalization; it would be odd in an era of globalization for so much of the world's reserves to be held in just one currency.

Thus Pax today means globalization, and globalization means a lower dollar. But the rub, of course, is that a lower dollar means a diminution of American power and, ultimately of its Pax.

Long term, I'm not worried; it's the short term I'm concerned about. As Sir Winston Churchill said, America always does the right thing, but only after exhausting all other options.

The USA has a lot more bad options to exhaust before doing the right thing.

Comment