|

Nov. 16 (Reed V. Landberg and Paul George - Bloomberg)

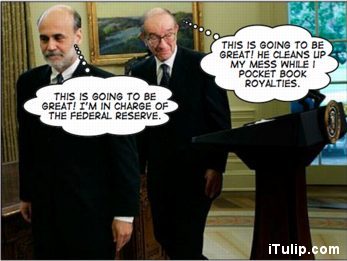

Joseph Stiglitz, a Nobel-prize winning economist, said the U.S. economy risks tumbling into recession because of the ``mess'' left by former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan.

``I'm very pessimistic,'' Stiglitz said in an interview in London today. ``Alan Greenspan really made a mess of all this. He pushed out too much liquidity at the wrong time. He supported the tax cut in 2001, which is the beginning of these problems. He encouraged people to take out variable-rate mortgages.''

AntiSpin: How exactly did this "mess" get here? We commented here on the reserve requirements, peso crisis, and other kindling for the stock bubble from 1995 and the all-out emergency reflation from the Greenspan Fed after the bubble collapsed. As I’ve said before, the Greenspan Fed held rates too low too long and was too slow and too predictable in normalizing them. This is not mere 20-20 hindsight. Economic statistics from 2002-2005 showed the credit bubble inflation to anyone who cared to look:

- October 2002 - Stock market bottoms. Unemployment rate is 5.7% Fed funds is at 1.75%. Housing bubble lifts off.

- July 2003 - US Stock prices up 26.5% in nine months. Commodity prices up 9.5% in nine months. Unemployment rate is 6.2%. Fed funds are cut to 1%.

- April 2004 - Stock prices up an additional 16.5% in nine months. Commodity prices up 29.7% in nine months. Unemployment rate is 5.5% Nominal GDP is up 6.5% year over year. Fed funds are still at 1%.

- July 2004 - Nominal GDP is up 7.2% year over year. FOMC finally hikes Fed funds 25 bp, embarking on a program of "removal of accommodation … at a pace that is likely to be measured". As it establishes a predictable pattern of 25 bp hikes, it tells the markets that even though it is raising rates, it is also giving them visibility in the sense of putting an effective ceiling on the forward trajectory of Fed funds, inviting a speculative bonanza of credit expansion. In other words, even as it is tightening in an absolute sense, it continues to ease by reducing a key element of credit market risk.

- July 2005 - Stock prices up an additional 10.1% year over year. Commodity prices up an additional 16.0%. The economy is said to be booming. Housing and energy prices have been galloping upward, doubling to tripling in a scant three to four years. The Fed continues its baby step program with a 25 bp Fed funds hike to 3.25%, touting low "core inflation", citing statistics that do not include energy, food, or houses. Money supply has been soaring at double-digit annual rates. This is just over a year after Greenspan himself made a speech to the Credit Union National Association extolling the benefits of adjustable rate mortgages. And for at least as long there have already been voices in the financial media warning of a credit bubble such as Doug Noland of Prudent Bear, and of housing bubble, notably Eric Janszen here at iTulip.

- October 2005 - US house prices are soaring to new all time highs. Oil is $70 a barrel. Double digit money supply growth continues. Not just oil, but virtually every physical commodity, including industrial metals, and foods, is experiencing breathaking price increases. Greenspan still insists inflation is moderate.

Greenspan has recently attempted to defend this abysmal record by citing the global nature of the housing and credit bubble. Like the misbehaving sixth-grader, it was okay because "everybody was doing it". Not to mention that central banks all over the world were taking their cues from the US Fed, driven at least in part by the fear of damaging their export industries by having their currencies appreciate too fast in relation to the US dollar. The maetro can hardly escape responsibility for the sonic disaster he leads.

The objective of delving into how we got in this mess is to learn from it. That the root cause of such crises takes a back seat to the immediate imperatives of how to make things better is one of the main reasons they occur in the first place. If the current crisis is "solved" by the same kind of thinking that created it, we cannot claim to have solved it at all.

Today's iTulip News by Shadow Fed Chairman, iTulip Select Member Finster.

Copyright © iTulip, Inc. 1998 - 2007 All Rights Reserved

All information provided "as is" for informational purposes only, not intended for trading purposes or advice. Nothing appearing on this website should be considered a recommendation to buy or to sell any security or related financial instrument. iTulip, Inc. is not liable for any informational errors, incompleteness, or delays, or for any actions taken in reliance on information contained herein. Full Disclaimer

Comment