|

- Webster's Seventh New Collegiate Dictionary

Why do speculative markets always end in panic selling? Think of speculative market investors as players in a game of musical chairs. The chairs represent the safe positions where a nimble investor winds up with cash proceeds from the sale of their securities at a high price when there are still many buyers, before the music stops. The alternative position, standing, is the position occupied by everyone else after the music stops. These players are stuck holding their securities for lack of a buyer as values drop 20%, 30%, 40%, 60%, 80%... In a selling panic, there are few if any buyers.

When the game is on, the players circle the row of chairs while an orchestra comprised of financial services company employees -- brokers, press agents, market analysts, and others involved in marketing and selling equities-based financial products to investors such as investment trusts in the 1920s and mutual funds now [hedge funds in 2007] -- play in concert with popular press reporters and editors, financial planners and other groupies who play off the same sheet music. Those who don't play off the same sheet music are labeled "contrarian" and are sent off to remote web sites where they can play their odd sounding music in obscurity.

Here's a recent example of how the popular press plays along. During the last days of August and the first days of September 1999, the DOW dropped several hundred points. The talking heads on CNBC said, "Don't worry. The trading is light. This volatility comes from amateurs trading in the absence of professional money managers who are all on vacation. When the pros get back from the Catskills, volumes will rise and volatility will fall." Then the amateurs exploded the market upwards more than 200 points on Friday still before the pros returned from vacation. The CNBC talking heads announced, "The market has resumed its rise." A rise in the market is reported as more significant than a fall under the same conditions. This is cooperative bull market reporting. St. Louis Fed economist reported one week later, "The party for stocks seems to be over but people won't go home because they just don't seem to know it's over yet.'' Small wonder. How are people going to know the game is over if the poplar press keep telling them the game's still on?

Why does the popular press play along? The audience for coverage that's negative in a speculative market is small and small audiences are uninteresting to large media organizations, especially those whose stock is publicly traded. It's never necessary to explain this to a reporter or editor any more than a dog needs to be told that biting the baby will result in a very short career as the family pet. Unlike the popular media outlets and especially television, the professional financial press -- the Wall Street Journal, Barron's and The Washington Post, for example -- diligently air evidence that the game has run its course. But do the majority of players in the game read these publications? (I suspect that the financial press professionals are at times irritated by the unbalanced reporting practiced by their pop press brethren.)

Central bankers want to appear hands-off and disinterested, focussed only on price stability and inflation in the real economy, ignoring the stock market. They go along with the game without playing in the musical chairs orchestra. They occasionally play a sour note, pointing out that the game may be getting near to the end. But the players hardly notice, such is the volume of the vast orchestra of television, newspaper, and magazines, of financial planners and pundit book authors, of brokers and trading firms, together playing the inspirational music for the great game of speculative market musical chairs.

But no game of musical chairs is supposed to last forever, as all the players know. After a while, sometimes gradually and sometimes suddenly, the orchestra begins to play off-key. A gentle rain has begun to fall and musicians can no longer read their music. The playing becomes dissonant. Confused and uncertain, the players look to each other for cues. Does this mean the music's going to stop soon? Of course, that's exactly what it means and at about the same moment almost all the players come to realize this. Then the orchestra suddenly stops playing and the players rush to sit down.

A speculative stock market is unlike musical chairs in one critical respect.

An investor takes money out of his pocket to buy stock. He thinks he still has that much net worth, but all he has is equity paper instead. If the price of the stock goes up he thinks he has more net worth. He can even use the stock as collateral to borrow more money to buy more stock.

Meanwhile the original money he spent to buy the stock goes to the guy he bought the stock from. The stock seller might put the money in the bank where someone else will borrow it or he in turn might buy the same stock himself, helping to drive the price up some more. Now the guy that he bought the stock from has the money that he got from the first guy he sold the stock to. And so on.

Add up the money that everyone thinks they've got and it's far more than what is really circulating. But as long as the boom continues everything is fine and the apparent "wealth" grows.

Some people after making a gain "hedge" their position. Some get involved with derivatives in other ways, producing even more apparent wealth along with apparent security.

What happens if a significant number of people all want to make a withdrawal?

That's when all the apparent wealth disappears.

It's a chain reaction. Collateral is gone so margin calls get generated. More withdrawals. More chain reaction.

Funny things happen. Some positions are short positions or hedge positions. When they get covered the price of the affected item goes UP!

So when the bust finally runs it's course a few lucky people who were in the right musical chair at the time have all the original money that was used to buy the stocks and the others go bust. Wondering where it all went. That's how guys like Rockeller and J. P. Morgan got their fortunes just before what was The Great Depression for everyone else.

The Fed can and will move to drop interest rates to provide liquidity to meet the demands for cash that occur in a stock market panic. But there is always a point of no return where you are going to go over the falls no matter how hard you paddle.

So the game of stock market mania musical chairs is unlike the parlor game. Rather than ten players and nine chairs, there are instead ten players and only one chair. If you are still in the game at the time this is published, that means you believe either the music will never stop or that you are quick enough to beat the other nine players to that one chair when it does.

Once the stock market speculation game is over, a new game will begin. Will it be a bond game? A commodity game? (I expect a commodity game as the world's dollar money supply is increased to counter deflation, and US interest rates are raised to defend a falling dollar, after the equity speculation game ends.) Whatever the new game is, a new group of players who were not financially ruined by the last game will come out to circle the chairs in the next speculative mania. The orchestra composed of financial services companies marketing new products, brokers selling them, reporters covering them, central bankers on the sidelines, will pull out new sheet music and begin to play.

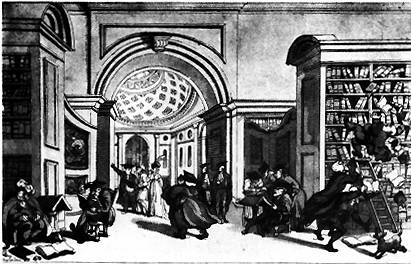

History brims with financial manias, from the real estate bubble collapse in Athens in 333 BC to the Mississippi Bubble in 1720 to the US Cotton Panic in 1837 to the French Credit Mobilier Debacle in 1868 to the The Great Crash in the US in 1929, and on and on. The lessons are ignored and the errors repeated. To the game's players, every financial mania is new. Perhaps history is not composed of facts after all. Maybe history is a language in which the dead speak to the deaf.

- iTulip, March 2000

When the game is on, the players circle the row of chairs while an orchestra comprised of financial services company employees -- brokers, press agents, market analysts, and others involved in marketing and selling equities-based financial products to investors such as investment trusts in the 1920s and mutual funds now [hedge funds in 2007] -- play in concert with popular press reporters and editors, financial planners and other groupies who play off the same sheet music. Those who don't play off the same sheet music are labeled "contrarian" and are sent off to remote web sites where they can play their odd sounding music in obscurity.

Here's a recent example of how the popular press plays along. During the last days of August and the first days of September 1999, the DOW dropped several hundred points. The talking heads on CNBC said, "Don't worry. The trading is light. This volatility comes from amateurs trading in the absence of professional money managers who are all on vacation. When the pros get back from the Catskills, volumes will rise and volatility will fall." Then the amateurs exploded the market upwards more than 200 points on Friday still before the pros returned from vacation. The CNBC talking heads announced, "The market has resumed its rise." A rise in the market is reported as more significant than a fall under the same conditions. This is cooperative bull market reporting. St. Louis Fed economist reported one week later, "The party for stocks seems to be over but people won't go home because they just don't seem to know it's over yet.'' Small wonder. How are people going to know the game is over if the poplar press keep telling them the game's still on?

Why does the popular press play along? The audience for coverage that's negative in a speculative market is small and small audiences are uninteresting to large media organizations, especially those whose stock is publicly traded. It's never necessary to explain this to a reporter or editor any more than a dog needs to be told that biting the baby will result in a very short career as the family pet. Unlike the popular media outlets and especially television, the professional financial press -- the Wall Street Journal, Barron's and The Washington Post, for example -- diligently air evidence that the game has run its course. But do the majority of players in the game read these publications? (I suspect that the financial press professionals are at times irritated by the unbalanced reporting practiced by their pop press brethren.)

Central bankers want to appear hands-off and disinterested, focussed only on price stability and inflation in the real economy, ignoring the stock market. They go along with the game without playing in the musical chairs orchestra. They occasionally play a sour note, pointing out that the game may be getting near to the end. But the players hardly notice, such is the volume of the vast orchestra of television, newspaper, and magazines, of financial planners and pundit book authors, of brokers and trading firms, together playing the inspirational music for the great game of speculative market musical chairs.

But no game of musical chairs is supposed to last forever, as all the players know. After a while, sometimes gradually and sometimes suddenly, the orchestra begins to play off-key. A gentle rain has begun to fall and musicians can no longer read their music. The playing becomes dissonant. Confused and uncertain, the players look to each other for cues. Does this mean the music's going to stop soon? Of course, that's exactly what it means and at about the same moment almost all the players come to realize this. Then the orchestra suddenly stops playing and the players rush to sit down.

A speculative stock market is unlike musical chairs in one critical respect.

An investor takes money out of his pocket to buy stock. He thinks he still has that much net worth, but all he has is equity paper instead. If the price of the stock goes up he thinks he has more net worth. He can even use the stock as collateral to borrow more money to buy more stock.

Meanwhile the original money he spent to buy the stock goes to the guy he bought the stock from. The stock seller might put the money in the bank where someone else will borrow it or he in turn might buy the same stock himself, helping to drive the price up some more. Now the guy that he bought the stock from has the money that he got from the first guy he sold the stock to. And so on.

Add up the money that everyone thinks they've got and it's far more than what is really circulating. But as long as the boom continues everything is fine and the apparent "wealth" grows.

Some people after making a gain "hedge" their position. Some get involved with derivatives in other ways, producing even more apparent wealth along with apparent security.

What happens if a significant number of people all want to make a withdrawal?

That's when all the apparent wealth disappears.

It's a chain reaction. Collateral is gone so margin calls get generated. More withdrawals. More chain reaction.

Funny things happen. Some positions are short positions or hedge positions. When they get covered the price of the affected item goes UP!

So when the bust finally runs it's course a few lucky people who were in the right musical chair at the time have all the original money that was used to buy the stocks and the others go bust. Wondering where it all went. That's how guys like Rockeller and J. P. Morgan got their fortunes just before what was The Great Depression for everyone else.

The Fed can and will move to drop interest rates to provide liquidity to meet the demands for cash that occur in a stock market panic. But there is always a point of no return where you are going to go over the falls no matter how hard you paddle.

So the game of stock market mania musical chairs is unlike the parlor game. Rather than ten players and nine chairs, there are instead ten players and only one chair. If you are still in the game at the time this is published, that means you believe either the music will never stop or that you are quick enough to beat the other nine players to that one chair when it does.

Once the stock market speculation game is over, a new game will begin. Will it be a bond game? A commodity game? (I expect a commodity game as the world's dollar money supply is increased to counter deflation, and US interest rates are raised to defend a falling dollar, after the equity speculation game ends.) Whatever the new game is, a new group of players who were not financially ruined by the last game will come out to circle the chairs in the next speculative mania. The orchestra composed of financial services companies marketing new products, brokers selling them, reporters covering them, central bankers on the sidelines, will pull out new sheet music and begin to play.

History brims with financial manias, from the real estate bubble collapse in Athens in 333 BC to the Mississippi Bubble in 1720 to the US Cotton Panic in 1837 to the French Credit Mobilier Debacle in 1868 to the The Great Crash in the US in 1929, and on and on. The lessons are ignored and the errors repeated. To the game's players, every financial mania is new. Perhaps history is not composed of facts after all. Maybe history is a language in which the dead speak to the deaf.

- iTulip, March 2000

Comment