|

April 3, 2007 (A.M. Best Banking Report)

A prominent feature of the U.S. banking industry’s fourth quarter 2006 results were noticeable increases in other real estate owned (OREO) and real estate charge-offs of 9% and 33%, respectively, and in emerging past due real estate loans, which increased by 21%. This leads to the question of whether loan loss reserves are sufficient for the industry. The question is even more pertinent for the smaller banks, which exhibit concentrations in higher risk commercial real estate and construction loans: 25% and 14% of total loan and leases, respectively.

While the banking industry’s absolute capital levels are high, and improvements have been seen in credit card portfolios and fixed rate mortgages, these positive developments have been more than offset by sharply declining quality in adjustable-rate mortgages and other real estate loan classes, such as commercial real estate. The low delinquency and charge-off rates of the past several years may have encouraged the assumption of additional risks without additional loss provisions. Of note, loan loss reserves are down to levels not seen since 1985, while past dues are ticking upward. The historical context of past downturns in the economic cycle, as well as the forward looking credit quality indicator of 30- to 89-day past due loans for the industry, provide an interesting perspective on the adequacy of current reserve levels.

Looking back historically, the last time loan loss reserves declined to these levels was 1985. Interestingly, that time period preceded a real estate downturn for which banks were not prepared. The confluence of the industry’s low reserves in the mid-1980s and the onslaught of one of the most severe real estate market corrections had all the ingredients of a perfect storm that wreaked havoc on U.S. banks for more than a decade later. Whether or not higher reserve levels back in 1985 might have made any difference in the state of the U.S. banking industry during the real estate market correction is another matter. The historical context of cyclical patterns for real estate loans and the industry’s exposures to this asset class is seen by the peaks of noncurrent loan rates at the time of or shortly following the 1985/1986 slowdown, the 1990/1991 recession and the 2000 recession as seen in the graph. Indications that the economy may be slowing, once again, beg the question of how adequate are current levels of bank loss reserves.

As yet another indicator of the potential for the U.S. banking industry’s 2006 year-end reserve levels to prove inadequate for deteriorating credit risk profiles, the fourth-quarter rise in delinquencies included a troubling increase in the emerging 30- to 89-day past-due category. Historically, these delinquencies are a precursor to more serious delinquencies, which ultimately may lead to loan losses. Another way of stating it: Regard the 30- to 89-day past dues as the pipeline that ultimately feeds into the 90+ past dues and the non-accruals (albeit perhaps not dollar for dollar). With a groundswell of the 30- to 89-day past dues underpinning the 90+ day past dues and non-accruals, the industry reasonably can be expected to face ever-rising delinquencies in the latter category in the coming months and quarters.

The trends of rising delinquencies and deteriorating asset quality in all asset-quality indicators, including OREO, charge-offs, 90+ past dues and non-accruals, and the 30- to 89-day past-due increases, lends further credence to the troubling aspect of the reserve levels being the lowest since 1985. In the fourth quarter, the more advanced stage 90+ non-accrual category already had increased by 14% for all real estate projects and a whopping 31% for the highest risk construction and development loans. If even half of the emerging 30- to 89-day delinquencies were to move through the pipeline to be included with these loans, the result would be 90+ days non-accrual loans of $92.7 billion, overwhelming an industry loan loss reserve of $77.6 billion.

This study is available electronically from the A.M. Best Co. Web site at www.ambest.com.

AntiSpin: We asked last week, Can the U.S. economy digest the trillion dollar ARMs egg? In the event, it appears that it's the U.S. banking system is likely to get indigestion.

Don't recall what happened to the banking system in the 1990s? Top three events were:

1) More than 1,600 banks failed.

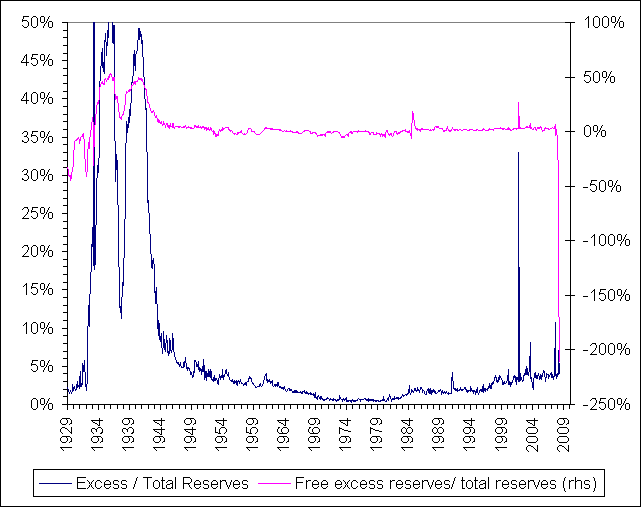

2) Banks went to the "discount window" to borrow from the Fed often during the period.

3) The banking system for a six month period in late 1994 virtually stopped lending.

This led to the reserve and account sweeps rule changes that iTulip's Aaron Krowne (now of Mortgage Lender Implode fame) wrote about for iTulip in What (Really) Happened in 1995?

What led up to this crisis? According to the June 2000 FDIC report, An Examination of the Banking Crises of the 1980s and Early 1990s:

During most of the 1980s, the performance of the national economy, as measured by broad economic aggregates, seemed favorable for banking. After the 1980–82 recession the national economy continued to grow, the rate of inflation slowed, and unemployment and interest rates declined. However, in the 1970s a number of factors, both national and international, had injected greater instability into the environment for banking, and these earlier developments were directly or indirectly generating challenges to which not all banks would be able to adapt successfully. In the 1970s, exchange rates among the world's major currencies became volatile after they were allowed to float; price levels underwent major increases in response to oil embargoes and other external shocks; and interest rates varied widely in response to inflation, inflationary expectations, and anti-inflationary Federal Reserve monetary policy actions.

Developments in the financial markets in the late 1970s and 1980s also tested the banking industry. Intrastate banking restrictions were lifted, allowing new players to enter once-sheltered markets; regional banking compacts were established; and direct credit markets expanded. In an environment of high market rates, the development of money market funds and the deregulation of deposit interest rates exerted upward pressures on interest expenses–particularly

for smaller institutions that were heavily dependent on deposit funding.

Competition increased from several directions: within the U.S. banking industry itself and from thrift institutions, foreign banks, and the commercial paper and junk bond markets. The banking industry's share of the market for loans to large business borrowers declined, partly because of technological innovations and innovations in financial products. As a result, many banks shifted funds to commercial real estate lending–an area involving greater risk. Some large banks also shifted funds to less-developed countries and leveraged buyouts, and increased their off-balance-sheet activities.

To answer the FDIC's 2000 question, Lessons Learned? Not many. Low loan loss reserves? Check. Competition from credit markets? Check. Avoiding competition and increasing profits by shifting funds to high risk real estate lending, junk bonds, LBOs, and emerging markets? Check, check, check, and check.Developments in the financial markets in the late 1970s and 1980s also tested the banking industry. Intrastate banking restrictions were lifted, allowing new players to enter once-sheltered markets; regional banking compacts were established; and direct credit markets expanded. In an environment of high market rates, the development of money market funds and the deregulation of deposit interest rates exerted upward pressures on interest expenses–particularly

for smaller institutions that were heavily dependent on deposit funding.

Competition increased from several directions: within the U.S. banking industry itself and from thrift institutions, foreign banks, and the commercial paper and junk bond markets. The banking industry's share of the market for loans to large business borrowers declined, partly because of technological innovations and innovations in financial products. As a result, many banks shifted funds to commercial real estate lending–an area involving greater risk. Some large banks also shifted funds to less-developed countries and leveraged buyouts, and increased their off-balance-sheet activities.

Appears that all we need to get a repeat show on the road is exchange rate volatility and higher interest rates. And that can't happen again, can it?

(See iTulip Select interview of Jim Rogers today.)

p.s. You won't see the A.M. Best story or the FDIC study on other sites as of 5:24PM ET today, but you will soon!

Comment