Why the Fed Didn't Raise Interest Rates

March 21, 2007 (Peter Coy - BusinessWeek)

Inflation is running above the levels that Bernanke has targeted, but he's holding off on hiking rates because of the risks

Imagine you're driving a car with a blacked-out windshield and a loose steering wheel. Now imagine that your car is the $13 trillion U.S. economy. That should give you some idea of what it feels like to be Federal Reserve Chairman Ben S. Bernanke. Yes, in a word: scary.

AntiSpin: That's close to last night's opinion of the iTulip ShadowFed. The Fed wants to cut, because of the ongoing collapse of the housing market and attendant negative wealth effects on consumption. Inflation data–such as it is, without either M3 or recent 30-year bond auction prices to better inform the markets of long term inflation risks–shows inflation running hot, and all eyes on the dollar, as the entire planet is now waiting to see if the U.S. will default on its more than $8 trillion foreign debt via inflation. So, the Fed has to wait. We describe it as the "Fly around in the fog until you hit something, then cut rates" policy.

The FOMC did what the ShadowFed expected, but now what it recommended. The advice from our board was a tougher stance on inflation. We didn't get that, and the dollar took it in the shorts.

Dollar At 2-Year Low Vs Euro As Fed Softens Tone

March 21, 2007 (Dow Jones)

The dollar sank to a two-year low against the euro Wednesday after the Federal Reserve softened its rate tightening bias and backpeddled from previous upbeat comments on growth and inflation.

Gold shot up as the dollar weakened. The stock market rallied because... well, never mind the stock market. Mostly companies themselves are buyers (pdf).March 21, 2007 (Dow Jones)

The dollar sank to a two-year low against the euro Wednesday after the Federal Reserve softened its rate tightening bias and backpeddled from previous upbeat comments on growth and inflation.

If you are a financial writer in another country, what are you making of all this?

The US Economy: Dangerously Sick

March 21, 2007 (Zaman Today)

Normally I devote my column to an in-depth analysis of the Turkish economy in order to inform my readers, mostly foreigners, about the risks and opportunities of our economy. However, it is becoming increasingly obvious that instead of talking about domestic risk factors, we must concentrate on external ones, mainly stemming from the US economy.

Even if economists are, nowadays, talking about Chinese stock market fluctuations and their impact on the rest of the word, I think this is just a pseudo agenda, hiding the most threatening and impending agenda: the American disease.

To refresh your memory, on Jan. 31, 2007 the president of the United States gave his speech on the “State of the Economy” citing strong economic growth, record Dow Jones performance and low unemployment rates. Despite this seemingly rosy picture based on some selective figures, today we are talking about the fundamental deficiencies of the US economy as a major source of global instability in the world economy.

Previously supportive foreign financial press are starting to call the U.S. economy "dangerous." How about the thought leaders among the U.S. financial press?March 21, 2007 (Zaman Today)

Normally I devote my column to an in-depth analysis of the Turkish economy in order to inform my readers, mostly foreigners, about the risks and opportunities of our economy. However, it is becoming increasingly obvious that instead of talking about domestic risk factors, we must concentrate on external ones, mainly stemming from the US economy.

Even if economists are, nowadays, talking about Chinese stock market fluctuations and their impact on the rest of the word, I think this is just a pseudo agenda, hiding the most threatening and impending agenda: the American disease.

To refresh your memory, on Jan. 31, 2007 the president of the United States gave his speech on the “State of the Economy” citing strong economic growth, record Dow Jones performance and low unemployment rates. Despite this seemingly rosy picture based on some selective figures, today we are talking about the fundamental deficiencies of the US economy as a major source of global instability in the world economy.

Once Again, Debt Is Miscast as the Villain

March 21, 2007 (New York Times)

The mortgage boom of the last few years wasn’t an isolated phenomenon. It was instead the newest way for consumers to go into debt. The small consumer loan of the Jenkses’ day begot the installment loan, which begot the credit card and eventually the interest-only adjustable-rate mortgage. Now, a lot of people are saying that the economy is finally going to pay the price for its spendthrift ways.

Which, when you stop and think about it, is roughly the same warning we have been hearing since at least 1912.

[Blah, blah, blah...]

The solution will have to involve new guidelines, voluntary or government-imposed, that force lenders to be clearer about the terms they’re offering borrowers. But as long as we take tough measures to clean up the mess, we’ll end up with a healthier mortgage market than we had beforehand. And then we can go looking for the next form of debt to captivate and torment us.

According to the NYTimes, the deflating housing bubble and soon to be collapsing consumer credit market are mere growing pains of the latest new-fangled form of credit: mortgage debt. In fact, the only thing new about this episode is the forgotten lesson of what happens when too many people take on too much of it on the assumption that asset prices and incomes will continue to rise forever. The NYT writer skips over at least one major event of the credit cycle which has occurred since 1912: The Great Depression.March 21, 2007 (New York Times)

The mortgage boom of the last few years wasn’t an isolated phenomenon. It was instead the newest way for consumers to go into debt. The small consumer loan of the Jenkses’ day begot the installment loan, which begot the credit card and eventually the interest-only adjustable-rate mortgage. Now, a lot of people are saying that the economy is finally going to pay the price for its spendthrift ways.

Which, when you stop and think about it, is roughly the same warning we have been hearing since at least 1912.

[Blah, blah, blah...]

The solution will have to involve new guidelines, voluntary or government-imposed, that force lenders to be clearer about the terms they’re offering borrowers. But as long as we take tough measures to clean up the mess, we’ll end up with a healthier mortgage market than we had beforehand. And then we can go looking for the next form of debt to captivate and torment us.

Consumers' borrowing is one of the most conspicuous danger points in the secondary phenomena of prosperity, and consumers' debts are among the most conspicuous weak spots in recession and depression.

In other words, we shall readily understand why the load of debt thus light heartedly incurred by people who foresaw nothing but booms should become a serious matter whenever incomes fell, and that construction would then contribute, directly and through the effects on the credit structure of impaired values of real estate, as much to a depression as it had contributed to the preceding booms. Nothing is so likely to produce cumulative depressive processes as such commitments of a vast number of households to an overhead financed to a great extent by commercial banks.

But under the circumstances of the 1920s boom and in the glow of its uncritical optimism, neither costs nor interest charges mattered much. It seemed more important to get quickly the home one wanted–or the skyscraper the prospective rents of which in any case compared favorably with the rare on mortgage bonds–than to bother whether it would cost a few thousand dollars–or in the case of the skyscraper, a million or so–more or less, provided money was readily forthcoming at those rates. And it was. First mortgages on urban real estate represent, on the one hand, not all the loans that were made available for building and, on the other hand, also financed not only other types of building but other things than building. But it is still permissible to point to the fact that they increased from, roughly, 13 billion in 1922 to, roughly, 27 in 1929... This increase is out of all proportion, not only with the increase in what can in any reasonable sense be called savings, but also with the expansion of bank credit in other lines of business, and illustrates well how a cheap money policy may affect other sectors than those in which it is conspicuously successful in bringing down rates.

- Joseph A. Schumpeter, "Business Cycles," 1939

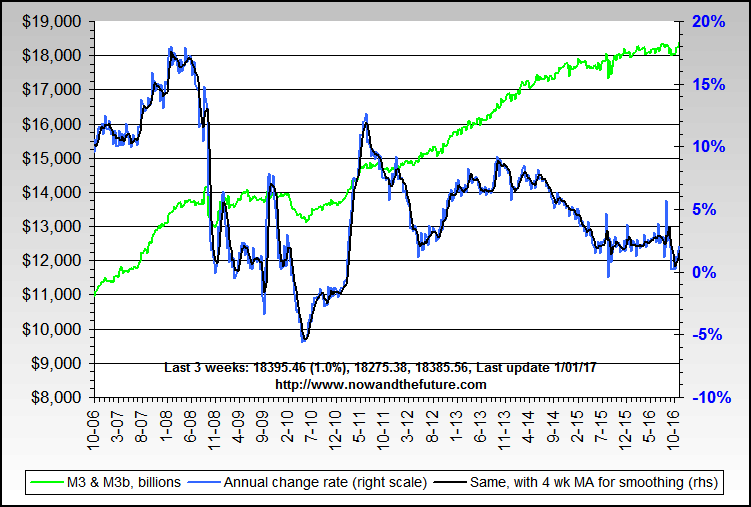

Such quaint numbers, 13 billion and 27 billion. What might Schumpeter make of this?In other words, we shall readily understand why the load of debt thus light heartedly incurred by people who foresaw nothing but booms should become a serious matter whenever incomes fell, and that construction would then contribute, directly and through the effects on the credit structure of impaired values of real estate, as much to a depression as it had contributed to the preceding booms. Nothing is so likely to produce cumulative depressive processes as such commitments of a vast number of households to an overhead financed to a great extent by commercial banks.

But under the circumstances of the 1920s boom and in the glow of its uncritical optimism, neither costs nor interest charges mattered much. It seemed more important to get quickly the home one wanted–or the skyscraper the prospective rents of which in any case compared favorably with the rare on mortgage bonds–than to bother whether it would cost a few thousand dollars–or in the case of the skyscraper, a million or so–more or less, provided money was readily forthcoming at those rates. And it was. First mortgages on urban real estate represent, on the one hand, not all the loans that were made available for building and, on the other hand, also financed not only other types of building but other things than building. But it is still permissible to point to the fact that they increased from, roughly, 13 billion in 1922 to, roughly, 27 in 1929... This increase is out of all proportion, not only with the increase in what can in any reasonable sense be called savings, but also with the expansion of bank credit in other lines of business, and illustrates well how a cheap money policy may affect other sectors than those in which it is conspicuously successful in bringing down rates.

- Joseph A. Schumpeter, "Business Cycles," 1939

Comment