Most Hedge Funds Suck, and that's Bad News for the Industry and Investors

An ounce of regulation is worth a pound of cure, but it's probably too late

Chris Calnan is interviewing me last week for this article Mass High Tech piece on iTulip, Inc. It appeared Monday, an article of local interest and perhaps not so interesting to the 99.9% of our community that does not reside in the Boston area, never mind the 30% of readers who do not even reside in the United States. Chris is asking, "Why are you so down on hedge funds?" For eight reasons. But before I get into those, I'll tell you why I like them.

Some hedge funds, like some venture capital (VC) funds, are run by highly experienced, disciplined, honest, hard working, smart men and women who make money for their clients and don't take all the money out of the funds they manage to which they are contractually entitled. Instead, they re-invest most and sometimes all of the money the fund earns that is technically theirs. The best hedge fund managers are creative with money the way software engineers are creative about solving business problems with software programs. They can take money and make more out of it in clever ways, producing higher returns than mutual funds or other funds, with not much more volatility or risk. These good hedge funds use carefully developed proprietary event driven, relative value, or macro tactical trading models, proprietary algorithms by analogy to the software industry. This is all good. Problem is, not many hedge funds are this good. Most so-called "hedge funds" suck. Let me count the ways.

1. Are not really "hedge funds" but USIPs (Unregulated Speculative Investment Pools) that expose investors to unnecessary risks.

Many so-called hedge funds are not long/short and hedged but are long and not hedged, leading to high returns while the trade goes their way and to massive losses when it doesn't. Leading to #2.

2. Invest in markets they don't understand, such as commodities, leading to losses for investors.

3. Even if truly a long/short fund, most see returns that are no better than a well balanced portfolio of stocks and bonds, but hedge funds routinely represent otherwise and charge big management fees.

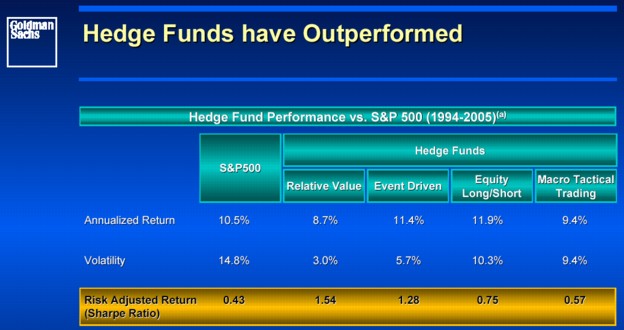

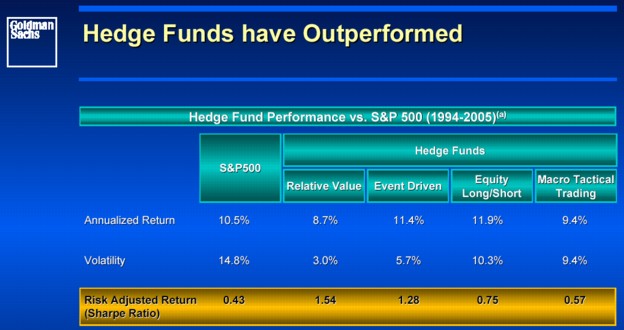

This report on hedge funds by J. Michael Evans of Goldman Sachs (pdf)–which is largely what Goldman has become–is typical of the industry case for hedge funds. It shows long/short hedge funds beating the S&P for years with lower volatility and risk:

Yet all independent analysis, such as this report by Michael Markov (pdf) of Markov Processes International, LLC, shows that this is not true.

Unfortunately, many hedge fund managers do not reinvest earnings back into their funds. The managers pocket a two percent fee and 20% of profits rather than re-invest it. Even if their investment strategies fail to generate returns, sharing 2% of, say, a $2 billion fund annually–$40 million–among a few managers is a good living for anyone. This is, of course, the real attraction of opening as hedge fund. In this "can't lose" world where one's net worth multiplies whether one fails to meet return objectives or not, what incentive does a fund manager have to get creative, work hard and not screw up? You might guess career risk, but you'd have guessed wrong. Fund managers can get poor results in one fund but have little trouble finding employment at a new fund.

4. Are followers without original trading ideas, leading to marginal average returns relative to cost.

Most do not use carefully developed proprietary trading schemes, but rather follow each other. Thus you see a macro hedge fund executing yet another variation on the yen carry trade–borrowing yen at low interest rates and buying dollars at high interest rates and banking the difference between what one pays in interest in yen (nothing) and earns in interest in U.S. bonds, say, 6%. That works swell until too many people are doing it at which point the differential demand for yen makes the yen rise relative to the dollar, wiping out your profits in a negative exchange rate differential. No free lunch.

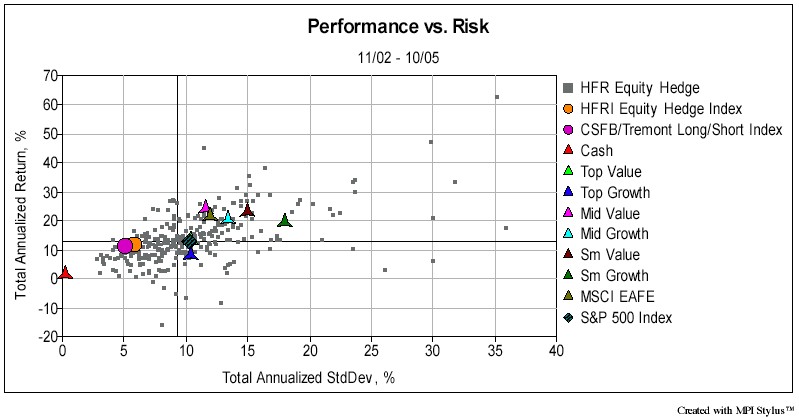

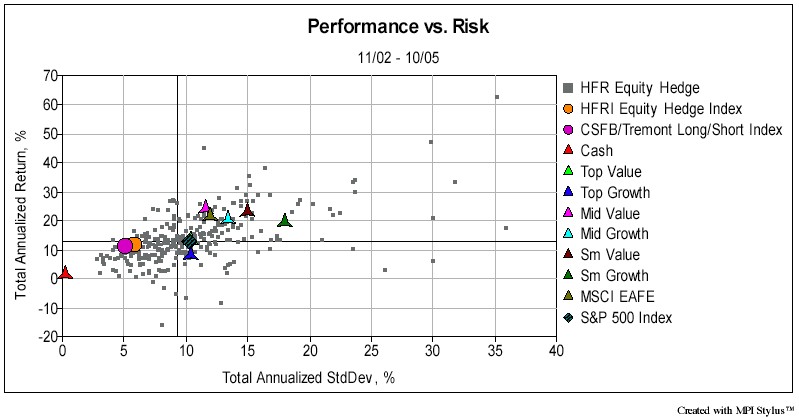

This chart from Markov shows cash as a red marker at the zero/zero on the axes–zero return and zero standard deviation (risk). The S&P is the green diamond at 12% return and around a 10% standard deviation. The Hedge Fund Return Index (HFRI) is the orange circle with an 11% return and 6% standard deviation. Is the approximate 30% better return on risk worth the 2% management fee and 20% of earnings over time? Probably not.

5. Reliance on liquidity, leading to likely future period of mass redemptions and fund closures when liquidity inevitably declines as with VC funds 2001 - 2003.

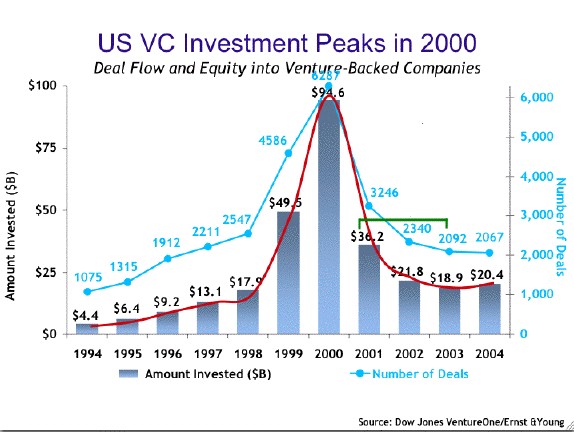

The phrase "When the wind blows hard enough, even turkeys fly" applies as much to many of today's hedge funds as to the low grade VC funds that sprang up in 1999 and 2000 and the uneconomical companies they funded, all of which subsequently fell to the ground after the wind died down. No doubt the hedge fund old timers are looking on in horror as liquidity rewards even the most careless behavior of some of the newly established firms and carries capital off to certain demise from high net worth individuals and institutions that apparently didn't learn their lesson in liquidity driven VC boom that ended in 2000. When these USIPs inevitably fail, they will for a couple of years drag down hedge funds as an "asset class," and I use that term loosely, for as Markov points out, most behave too much like stock mutual and stock index funds to qualify as a distinct class. However, just as with the case of VC funds, the top quintile hedge funds will survive the downturn and attract the bulk of new investment for the class, leaving a few thousand low grade funds to die out.

6. Investing in companies in ways that are virtually guaranteed to deliver losses to investors.

As my friend "J" explains in his post World Needs Better "Face of American Capitalism” than Private Equity, Goldman Sachs, Media Freak Show, many hedge funds, like some private equity funds, try to participate in companies as active investors. Problem is that most, though not all, hedge fund managers, like most but not all PE general partners, cannot operate a company. Why does that matter? Two reasons.

One, they can't really understand what a company is doing because they cannot relate personal experience to what the management team is trying to accomplish. If the company is under duress, such as during a recession, the easy way out of for hedge funds under pressure from other shareholders to "fix things" is to change the management team, even if that is the worst possible thing for the company at that time, creating a source of internal turbulence as severe as the external source. Two, investors sometimes need to threaten war with management. When investors are not in a position to run the company because they lack the skills, management calls the bluff and–lacking the means to back up their threats because they are unable to operate a company–the hedge fund and PE guys either have to back down, to the detriment of shareholders, or–God help us–take on responsibilities they cannot fulfill, such as management roles, also to the detriment of investors. Lose, lose. Whether VCs, hedge fund managers, or private equity partners, taking an active investor role in a corporation is for finance people with operating experience. Period. In the long run, everyone else loses. Everyone: shareholders, management, employees, customers, and society at large. The problem is that liquidity, while it lasts, papers over this fundamental weakness in structure of boards that have non-operators in control as investors. Weaknesses in the capital structure, due to debt obligations that were economical during boom times but will not be in a recession when demand and revenues will decline, will create a splatter pattern across the U.S. economy, familiar to ex-dot com employees, as dozens of these turkeys hurdle to the ground next year.

7. Contributing little to the economy and society.

Successful capitalism is about cultivating the innate capacity of humans to produce incremental value for themselves and each other. Incremental as in not re-inventing the wheel but inventing something new on top of what has been invented before. The marvel of humans is that we can take all that has ever existed in history and continuously make it better. In your own experience, think of cars. Compare the car you own today to the one you owned 20 years ago. Didn't start in the winter. Left you on the side of the road at least once a year. And how did you call anyone for help? Pay phone. Quaint, isn't it? But it gets better. The improvements that will come out of developments in new technologies like biotech will rock your world. I am equally optimistic that technologies that allow us to conserve energy will push Peak Oil out on a long, declining curve versus falling off a cliff as many Peak Oilers predict.

Most of the thousands of people currently running hedge funds are not adding anything productive to the economy. While China and India crank out hundreds of thousands of engineers–either U.S. educated or locally–who create inventions that Chinese and Indian corporations can turn into profits, the U.S cranks out an equal number of finance professionals to manage and speculate with the assets which result from the capital formed by new inventions. In the long run, the nation that produces more of the former and less of the latter will maintain a better standard of living for its citizens over time.

The growing gap shows up not in the U.S. engineering school enrollment numbers, as many Chinese, Indian, and Korean students continue to come to the U.S. for training. Rather the gap shows up in R&D investment, which is a function of both where those students go after they are trained–home–and how they are deployed in the economy. A recent report by the American Institute of Physics explains:

8. Tragedy of the commons: bad hedge funds will drive out good capital, invite collective punishment of the innocent by regulators that will stymie the hedge fund industry for years.

Just as the post-stock market bubble Sarbanes-Oxley rules collectively punished innocent corporations while leaving most of the perpetrators of legal investment fraud in the 1990s free to go with their lottery winnings, after the current batch of liquidity dries up, many hedge funds fail, and investors put pressure on government regulators to prevent a repeat, the good hedge funds will get whacked along with the bad. You can already see it coming.

___

To receive the iTulip Newsletter or iTulip Alerts, Join our FREE Email Mailing List

Copyright © iTulip, Inc. 1998 - 2006 All Rights Reserved

All information provided "as is" for informational purposes only, not intended for trading purposes or advice. Nothing appearing on this website should be considered a recommendation to buy or to sell any security or related financial instrument. iTulip, Inc. is not liable for any informational errors, incompleteness, or delays, or for any actions taken in reliance on information contained herein. Full Disclaimer

An ounce of regulation is worth a pound of cure, but it's probably too late

Chris Calnan is interviewing me last week for this article Mass High Tech piece on iTulip, Inc. It appeared Monday, an article of local interest and perhaps not so interesting to the 99.9% of our community that does not reside in the Boston area, never mind the 30% of readers who do not even reside in the United States. Chris is asking, "Why are you so down on hedge funds?" For eight reasons. But before I get into those, I'll tell you why I like them.

Some hedge funds, like some venture capital (VC) funds, are run by highly experienced, disciplined, honest, hard working, smart men and women who make money for their clients and don't take all the money out of the funds they manage to which they are contractually entitled. Instead, they re-invest most and sometimes all of the money the fund earns that is technically theirs. The best hedge fund managers are creative with money the way software engineers are creative about solving business problems with software programs. They can take money and make more out of it in clever ways, producing higher returns than mutual funds or other funds, with not much more volatility or risk. These good hedge funds use carefully developed proprietary event driven, relative value, or macro tactical trading models, proprietary algorithms by analogy to the software industry. This is all good. Problem is, not many hedge funds are this good. Most so-called "hedge funds" suck. Let me count the ways.

1. Are not really "hedge funds" but USIPs (Unregulated Speculative Investment Pools) that expose investors to unnecessary risks.

Many so-called hedge funds are not long/short and hedged but are long and not hedged, leading to high returns while the trade goes their way and to massive losses when it doesn't. Leading to #2.

2. Invest in markets they don't understand, such as commodities, leading to losses for investors.

"Amaranth, based in Greenwich CT, specialized in energy trading. But the collapse in natural gas prices forced it out of its positions after its two main funds plunged more than $6 billion, or 65%, since the end of August. It’s the largest hedge fund collapse since LTCM went belly up in 1998."

Amaranth and Hedge Funds’ Hidden Risks, Jeremy Siegel Ph.D., Yahoo! Finance, December 2, 2006

Anyone who invests other people's money (OPM) in commodities without having at least one professional on the fund management team with 20 years or more experience trading commodities is, in my opinion, utterly irresponsible. The commodities market is uniquely difficult place to find arbitrage opportunities, with pricing characteristics that are far more complex and volatile that other markets, such as bonds. Most hedge funds that trade in commodities–and currencies, for that matter–have no business doing so. Amaranth and Hedge Funds’ Hidden Risks, Jeremy Siegel Ph.D., Yahoo! Finance, December 2, 2006

3. Even if truly a long/short fund, most see returns that are no better than a well balanced portfolio of stocks and bonds, but hedge funds routinely represent otherwise and charge big management fees.

This report on hedge funds by J. Michael Evans of Goldman Sachs (pdf)–which is largely what Goldman has become–is typical of the industry case for hedge funds. It shows long/short hedge funds beating the S&P for years with lower volatility and risk:

Yet all independent analysis, such as this report by Michael Markov (pdf) of Markov Processes International, LLC, shows that this is not true.

"The above result is very important. It shows that on average, when investing in a long/short hedge fund, investors are essentially getting an equivalent of an asset allocation portfolio with a big chunk of assets invested in T-Bills. Typically, investors are not very happy when 50% of their investment is kept in cash. Here, they don't say a word – moreover, they pay premium fees to hedge funds for doing just that.

"Another important observation: since blue and red line almost match, there's very little if any alpha generated by the category as a whole. That is expected: there are very few good long/short funds and when you combine a large number of funds, alpha simply cancels out. One may argue that being in a 50/50 mix is an indication of skill by itself. This may be true, but it's worth noting that most of long/short strategies are being "sold" precisely on the premise of alpha generating. Note also that the above analysis is not limited to an obscure hedge fund index. We've seen very similar results with very close tracking in analysis of dozens Hedge Fund of Funds. Such funds produce very little alpha and most of the value comes from market exposure bets, something that investors should be aware of."

3. Have less skin in the game and lower risk than their investors, leading to limited accountability, low motivation for creativity and hard work, and poor judgment."Another important observation: since blue and red line almost match, there's very little if any alpha generated by the category as a whole. That is expected: there are very few good long/short funds and when you combine a large number of funds, alpha simply cancels out. One may argue that being in a 50/50 mix is an indication of skill by itself. This may be true, but it's worth noting that most of long/short strategies are being "sold" precisely on the premise of alpha generating. Note also that the above analysis is not limited to an obscure hedge fund index. We've seen very similar results with very close tracking in analysis of dozens Hedge Fund of Funds. Such funds produce very little alpha and most of the value comes from market exposure bets, something that investors should be aware of."

Unfortunately, many hedge fund managers do not reinvest earnings back into their funds. The managers pocket a two percent fee and 20% of profits rather than re-invest it. Even if their investment strategies fail to generate returns, sharing 2% of, say, a $2 billion fund annually–$40 million–among a few managers is a good living for anyone. This is, of course, the real attraction of opening as hedge fund. In this "can't lose" world where one's net worth multiplies whether one fails to meet return objectives or not, what incentive does a fund manager have to get creative, work hard and not screw up? You might guess career risk, but you'd have guessed wrong. Fund managers can get poor results in one fund but have little trouble finding employment at a new fund.

4. Are followers without original trading ideas, leading to marginal average returns relative to cost.

Most do not use carefully developed proprietary trading schemes, but rather follow each other. Thus you see a macro hedge fund executing yet another variation on the yen carry trade–borrowing yen at low interest rates and buying dollars at high interest rates and banking the difference between what one pays in interest in yen (nothing) and earns in interest in U.S. bonds, say, 6%. That works swell until too many people are doing it at which point the differential demand for yen makes the yen rise relative to the dollar, wiping out your profits in a negative exchange rate differential. No free lunch.

This chart from Markov shows cash as a red marker at the zero/zero on the axes–zero return and zero standard deviation (risk). The S&P is the green diamond at 12% return and around a 10% standard deviation. The Hedge Fund Return Index (HFRI) is the orange circle with an 11% return and 6% standard deviation. Is the approximate 30% better return on risk worth the 2% management fee and 20% of earnings over time? Probably not.

5. Reliance on liquidity, leading to likely future period of mass redemptions and fund closures when liquidity inevitably declines as with VC funds 2001 - 2003.

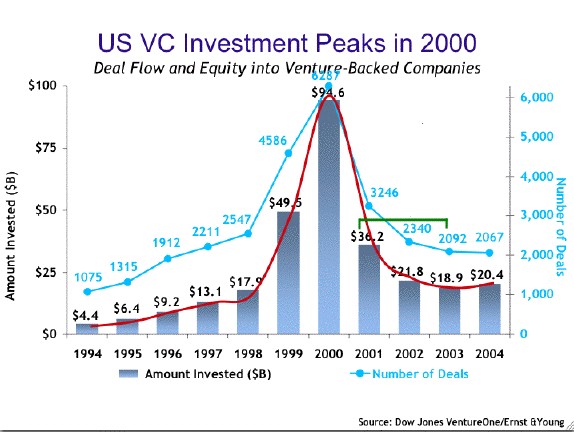

1990s VC funding bubble

The phrase "When the wind blows hard enough, even turkeys fly" applies as much to many of today's hedge funds as to the low grade VC funds that sprang up in 1999 and 2000 and the uneconomical companies they funded, all of which subsequently fell to the ground after the wind died down. No doubt the hedge fund old timers are looking on in horror as liquidity rewards even the most careless behavior of some of the newly established firms and carries capital off to certain demise from high net worth individuals and institutions that apparently didn't learn their lesson in liquidity driven VC boom that ended in 2000. When these USIPs inevitably fail, they will for a couple of years drag down hedge funds as an "asset class," and I use that term loosely, for as Markov points out, most behave too much like stock mutual and stock index funds to qualify as a distinct class. However, just as with the case of VC funds, the top quintile hedge funds will survive the downturn and attract the bulk of new investment for the class, leaving a few thousand low grade funds to die out.

6. Investing in companies in ways that are virtually guaranteed to deliver losses to investors.

As my friend "J" explains in his post World Needs Better "Face of American Capitalism” than Private Equity, Goldman Sachs, Media Freak Show, many hedge funds, like some private equity funds, try to participate in companies as active investors. Problem is that most, though not all, hedge fund managers, like most but not all PE general partners, cannot operate a company. Why does that matter? Two reasons.

One, they can't really understand what a company is doing because they cannot relate personal experience to what the management team is trying to accomplish. If the company is under duress, such as during a recession, the easy way out of for hedge funds under pressure from other shareholders to "fix things" is to change the management team, even if that is the worst possible thing for the company at that time, creating a source of internal turbulence as severe as the external source. Two, investors sometimes need to threaten war with management. When investors are not in a position to run the company because they lack the skills, management calls the bluff and–lacking the means to back up their threats because they are unable to operate a company–the hedge fund and PE guys either have to back down, to the detriment of shareholders, or–God help us–take on responsibilities they cannot fulfill, such as management roles, also to the detriment of investors. Lose, lose. Whether VCs, hedge fund managers, or private equity partners, taking an active investor role in a corporation is for finance people with operating experience. Period. In the long run, everyone else loses. Everyone: shareholders, management, employees, customers, and society at large. The problem is that liquidity, while it lasts, papers over this fundamental weakness in structure of boards that have non-operators in control as investors. Weaknesses in the capital structure, due to debt obligations that were economical during boom times but will not be in a recession when demand and revenues will decline, will create a splatter pattern across the U.S. economy, familiar to ex-dot com employees, as dozens of these turkeys hurdle to the ground next year.

7. Contributing little to the economy and society.

Successful capitalism is about cultivating the innate capacity of humans to produce incremental value for themselves and each other. Incremental as in not re-inventing the wheel but inventing something new on top of what has been invented before. The marvel of humans is that we can take all that has ever existed in history and continuously make it better. In your own experience, think of cars. Compare the car you own today to the one you owned 20 years ago. Didn't start in the winter. Left you on the side of the road at least once a year. And how did you call anyone for help? Pay phone. Quaint, isn't it? But it gets better. The improvements that will come out of developments in new technologies like biotech will rock your world. I am equally optimistic that technologies that allow us to conserve energy will push Peak Oil out on a long, declining curve versus falling off a cliff as many Peak Oilers predict.

Most of the thousands of people currently running hedge funds are not adding anything productive to the economy. While China and India crank out hundreds of thousands of engineers–either U.S. educated or locally–who create inventions that Chinese and Indian corporations can turn into profits, the U.S cranks out an equal number of finance professionals to manage and speculate with the assets which result from the capital formed by new inventions. In the long run, the nation that produces more of the former and less of the latter will maintain a better standard of living for its citizens over time.

The growing gap shows up not in the U.S. engineering school enrollment numbers, as many Chinese, Indian, and Korean students continue to come to the U.S. for training. Rather the gap shows up in R&D investment, which is a function of both where those students go after they are trained–home–and how they are deployed in the economy. A recent report by the American Institute of Physics explains:

“Fastest-growing economies continue to increase their R&D investments rapidly, nearly five times the rate of the United States: The countries of China, Ireland, Israel, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan collectively increased their R&D investments by 214 percent between 1995 and 2004. The United States in that period increased its total R&D investments by 43 percent.

“U.S. physical sciences and engineering research budgets significantly lag economic growth: As a share of GDP, the U.S. federal investment in both physical sciences and engineering research has dropped by half since 1970. In inflation-adjusted dollars, federal funding for physical sciences research has been flat for two decades. . . . Support for engineering research is similar.

“U.S. physical sciences and engineering research budgets significantly lag economic growth: As a share of GDP, the U.S. federal investment in both physical sciences and engineering research has dropped by half since 1970. In inflation-adjusted dollars, federal funding for physical sciences research has been flat for two decades. . . . Support for engineering research is similar.

“Innovators transform new knowledge into products and services. The United States has led the world in innovation and in the creation of knowledge that fuels this progress. Two benchmarks of knowledge creation, journal articles and patents, reveal that change around the world is eroding traditional U.S. leadership in these areas. Other countries are rapidly enlarging their stock of intellectual property assets and are expanding the boundaries of learning and discovery across all fields of science and engineering. Growth in patent applications around the world shows that these countries are also enhancing their abilities to put newly created knowledge to viable commercial uses.”

The rewards of speculation in the upside-down U.S. economy are creating perverse incentives that reward speculators and punish intellectual property makers. Engineer friends report that the ugly high risk, low return deals that VCs are offering them as founders of VC backed technology companies in the U.S. these days–leaving them with less than 50% ownership in the first round of funding–makes them feel, in the words of one founder recently, "punished for inventing versus speculating. I should quit engineering and start a hedge fund."8. Tragedy of the commons: bad hedge funds will drive out good capital, invite collective punishment of the innocent by regulators that will stymie the hedge fund industry for years.

Just as the post-stock market bubble Sarbanes-Oxley rules collectively punished innocent corporations while leaving most of the perpetrators of legal investment fraud in the 1990s free to go with their lottery winnings, after the current batch of liquidity dries up, many hedge funds fail, and investors put pressure on government regulators to prevent a repeat, the good hedge funds will get whacked along with the bad. You can already see it coming.

Tokyo watchdog targets hedge risks

December 22, 2006 (Michiyo Nakamoto – The Australian)

HAVING just emerged from a financial crisis, Japan again faces the risk of mounting bank failures - this time owing to their insatiable appetite for hedge funds.

That, at least, is the message coming from the financial regulator as it finalizes guidelines that would force Japanese banks to greatly increase their capital reserves against their exposure to certain hedge funds.

The Financial Services Agency's new rules, based on the Bank for International Settlement's Basle II standards, will from next March force banks to provide increased information on the hedge funds they invest in, or to put aside higher reserves that would make those investments economically unattractive for many banks. This requirement is particularly difficult to meet for the large number of regional banks that invest in funds of hedge funds or multi-strategy funds, and has triggered widespread redemptions and sales of hedge funds.

"People put their money in the bank because they believe it is safe. Is it OK to take those deposits and invest them in products they don't understand?" a senior official says.

The current hedge fund boom is yet another liquidity driven bubble like the VC bubble of the 1990s. After it collapses, over-regulation and negative investor sentiment will disable the industry for a while and, as sources of capital to many industries, their sudden departure from the market will damage those industries much as the technology industry was hammered by the collapse of the NASDAQ bubble and the exit of many VCs from the technology funding market. When it comes to regulations that distinguish good hedge funds from the bad, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. Apparently, the Fed, which supplies the liquidity, and the SEC, which is supposed to figure out how to effectively regulate funds to prevent abuses and limit the chance of market failures, are slow learners. Question is, how much more of this abuse can the U.S. economy take? We'd better hope it can take a lot because in 2007, the hedge fund, private equity and housing bubbles are all going to collapse together. December 22, 2006 (Michiyo Nakamoto – The Australian)

HAVING just emerged from a financial crisis, Japan again faces the risk of mounting bank failures - this time owing to their insatiable appetite for hedge funds.

That, at least, is the message coming from the financial regulator as it finalizes guidelines that would force Japanese banks to greatly increase their capital reserves against their exposure to certain hedge funds.

The Financial Services Agency's new rules, based on the Bank for International Settlement's Basle II standards, will from next March force banks to provide increased information on the hedge funds they invest in, or to put aside higher reserves that would make those investments economically unattractive for many banks. This requirement is particularly difficult to meet for the large number of regional banks that invest in funds of hedge funds or multi-strategy funds, and has triggered widespread redemptions and sales of hedge funds.

"People put their money in the bank because they believe it is safe. Is it OK to take those deposits and invest them in products they don't understand?" a senior official says.

___

To receive the iTulip Newsletter or iTulip Alerts, Join our FREE Email Mailing List

Copyright © iTulip, Inc. 1998 - 2006 All Rights Reserved

All information provided "as is" for informational purposes only, not intended for trading purposes or advice. Nothing appearing on this website should be considered a recommendation to buy or to sell any security or related financial instrument. iTulip, Inc. is not liable for any informational errors, incompleteness, or delays, or for any actions taken in reliance on information contained herein. Full Disclaimer

I do think you do a great job of illuminating all of the inequalities in the system Eric... anyone want to start an EJ for SEC Commissioner campaign?)

I do think you do a great job of illuminating all of the inequalities in the system Eric... anyone want to start an EJ for SEC Commissioner campaign?)

Comment