|

Our deflationista sparring partners were recently joined by a new voice, both thoughtful and earnest. We exchanged a few emails and found his case so compelling, his belief so pure, that the iTulip team was compelled to spring into action with Emergency Plan B to ensure that the central element of our now ten-year-old Ka-Poom Theory of post-bubble disinflation followed by inflation remains intact.

We deployed a data collection tool that we readied for just such an occasion, the iTulip Flying Fed Spy Cam, a camera and transmitter mounted on a tiny, radio-controlled helicopter, shown to scale above, ready to go to collect the critical intelligence at a moment’s notice. Faced with the possibility that the deflationistas had secretly located new data we have not seen since 1999, revelatory evidence that the Fed had lost its money creation mojo, our standby team launched the covert reconnaissance flight on short notice. Could the deflationistas be right? Is it possible that the Fed can't print? Can the government fail to execute double entry bookkeeping?

Overview of Credit Bubble Outcome Positions:

Deflationistas believe that the credit bubble that began in 1980 ends with a deflation spiral as in the US in the 1930s, with asset and goods prices falling, leading to self-reinforcing cycle of a collapse in the money supply, credit, and demand, as the Fed’s effort to re-inflate the economy via expansion of credit and the money supply fails. The heart of the argument is that the Fed cannot substitute enough government money and credit fast enough to compensate for the loss of private market money and credit as the credit bubble and economy collapse.

Hyperinflationistas believe that the Fed’s effort to re-inflate the money supply eventually succeed in destroying confidence in the currency. As the recession drags on, nominal tax revenues decline, sovereign creditworthiness declines along with output, and government loses the ability to fund fixed budget liabilities (i.e., those it cannot cut, such as military expenditure during times of war, legal obligations such as pensions, and public safety related expenses such as police and fire protection and infrastructure maintenance) through tax collections or by marketing more government debt to domestic or foreign creditors to finance government budgets. The Federal government begins to print money, that is, currency without an offset of new Federal government debt. Slowly at first, the purchasing power of tax revenue falls. The government prints more money to cover the decline in purchasing power, and a classic hyperinflation cycle sets in. The Hyperinflationistats see this as inevitable.

Congress approves spending, the Treasury issues new debt, the

Fed issues new currency against the debt, and the money supply expands.

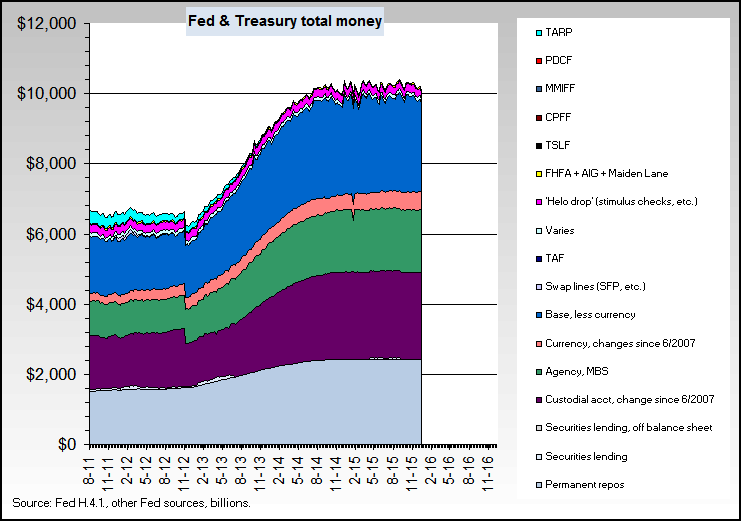

Inflationistas, led by iTulip in 1999 with our Ka-Poom Theory, follows a middle road. Call us optimists. It assumes no mechanical limitation in the Fed’s and Treasury’s ability to expand the money supply or substitute government for private credit, as depicted in the chart above.

The underlying post credit bubble macro-economic challenge is excessive debt, private and public, foreign and domestic, left over from the credit-dependent FIRE Economy. The US economy has to get rid of a large portion of the left over debt so that the US economy can move forward again. The phrase “get rid of the debt” is the most politically charged of the century, because to write off a debt means to not repay a creditor’s loan – savings -- on the other side of the ledger. To write off our foreign debt, for example, is to ask the Chinese, Japanese, Saudis, Russians and other creditors to forget about all the hard work they put into saving money to use buy US Treasury bonds. Within these countries such a decision is politically unacceptable, especially when economies are weakening as we expected they to during the period of recession that attends post credit bubble debt deflations; no politician can accept a write-off of the people’s hard earned savings at a time when savings are dear -- the US can’t pay, the creditor can’t forgive. Meanwhile the hyperinflationista’s case is building.

Ka-Poom Theory says that the ultimate outcome of this political conundrum problem is built into the structure of the foreign debt itself: if only the US can get its foreign creditors to start selling US debt, the dollar will weaken on global currency markets as dollars are exchanged for domestic creditors’ currencies. The weaker dollar deflates the foreign debt. The more the dollar deflates, the more the debt deflates. Of course, US interest rates and inflation rise to compensate new borrowers, but that increases domestic saving while the domestic inflation deflates the domestic debt, both private (household and business) and public (local and state government). The political question is, in this scenario, which savers are losing? Remember, savers lose when debt is written off, either explicitly or via inflation. The answer is that in inflation, all savers lose. Politically, inflation is a tax on all savers to pay all creditors, but the creditors pay, too, by loss of purchasing power of debts collected. The political advantages of inflation in a debt deflation crisis are obvious: savers and creditors share the pain, and to accomplish it all the government has to do is continue to do what it is already doing, without changing course. That is the basis of Ka-Poom Theory, the first theory of inflation, but not hyperinflation, as an outcome of the credit bubble.

Our highly skilled remote Fed Spy Cam pilot navigated the tiny craft through the cavernous Federal Reserve in Washington, D.C. from the entrance on 950 F Street, N.W. street all the way into the bowls -- and that is the word, believe us -- of the great institution. (If you have ever seen the movie Brazil, you can picture it.) Getting past security was the easy part, the doors guarded by the same men and women who watched over the US banking system for the past dozen years. Our challenge was locating the precise keyboard and monitor used by the Fed employee responsible for executing the day’s “more zeros” order. By comparing our Before Crisis Start and After Crisis Start images, we hoped to validate --- or invalidate – our now ten year old conviction: when faced with the need to print money, sans constraint of a gold standard, the Fed can and will issue more money against new or, in a pinch, existing debt (aka “debt monetization”). Deflationistas believe that the credit bubble that began in 1980 ends with a deflation spiral as in the US in the 1930s, with asset and goods prices falling, leading to self-reinforcing cycle of a collapse in the money supply, credit, and demand, as the Fed’s effort to re-inflate the economy via expansion of credit and the money supply fails. The heart of the argument is that the Fed cannot substitute enough government money and credit fast enough to compensate for the loss of private market money and credit as the credit bubble and economy collapse.

Hyperinflationistas believe that the Fed’s effort to re-inflate the money supply eventually succeed in destroying confidence in the currency. As the recession drags on, nominal tax revenues decline, sovereign creditworthiness declines along with output, and government loses the ability to fund fixed budget liabilities (i.e., those it cannot cut, such as military expenditure during times of war, legal obligations such as pensions, and public safety related expenses such as police and fire protection and infrastructure maintenance) through tax collections or by marketing more government debt to domestic or foreign creditors to finance government budgets. The Federal government begins to print money, that is, currency without an offset of new Federal government debt. Slowly at first, the purchasing power of tax revenue falls. The government prints more money to cover the decline in purchasing power, and a classic hyperinflation cycle sets in. The Hyperinflationistats see this as inevitable.

Congress approves spending, the Treasury issues new debt, the

Fed issues new currency against the debt, and the money supply expands.

Inflationistas, led by iTulip in 1999 with our Ka-Poom Theory, follows a middle road. Call us optimists. It assumes no mechanical limitation in the Fed’s and Treasury’s ability to expand the money supply or substitute government for private credit, as depicted in the chart above.

The underlying post credit bubble macro-economic challenge is excessive debt, private and public, foreign and domestic, left over from the credit-dependent FIRE Economy. The US economy has to get rid of a large portion of the left over debt so that the US economy can move forward again. The phrase “get rid of the debt” is the most politically charged of the century, because to write off a debt means to not repay a creditor’s loan – savings -- on the other side of the ledger. To write off our foreign debt, for example, is to ask the Chinese, Japanese, Saudis, Russians and other creditors to forget about all the hard work they put into saving money to use buy US Treasury bonds. Within these countries such a decision is politically unacceptable, especially when economies are weakening as we expected they to during the period of recession that attends post credit bubble debt deflations; no politician can accept a write-off of the people’s hard earned savings at a time when savings are dear -- the US can’t pay, the creditor can’t forgive. Meanwhile the hyperinflationista’s case is building.

Ka-Poom Theory says that the ultimate outcome of this political conundrum problem is built into the structure of the foreign debt itself: if only the US can get its foreign creditors to start selling US debt, the dollar will weaken on global currency markets as dollars are exchanged for domestic creditors’ currencies. The weaker dollar deflates the foreign debt. The more the dollar deflates, the more the debt deflates. Of course, US interest rates and inflation rise to compensate new borrowers, but that increases domestic saving while the domestic inflation deflates the domestic debt, both private (household and business) and public (local and state government). The political question is, in this scenario, which savers are losing? Remember, savers lose when debt is written off, either explicitly or via inflation. The answer is that in inflation, all savers lose. Politically, inflation is a tax on all savers to pay all creditors, but the creditors pay, too, by loss of purchasing power of debts collected. The political advantages of inflation in a debt deflation crisis are obvious: savers and creditors share the pain, and to accomplish it all the government has to do is continue to do what it is already doing, without changing course. That is the basis of Ka-Poom Theory, the first theory of inflation, but not hyperinflation, as an outcome of the credit bubble.

Here are iTulip’s exclusive Before and After shots of the keyboard where the really, really big numbers are entered.

Before...  After...

After...

After...

After...

See that darker shaded area on the zero key in the second picture? Clear evidence that the zero key has indeed seen a lot of action since the Before picture was taken.

For further confirmation we visited the St. Louis Fed’s website where -- lo and behold -- many zeros poured out the other end.

Money at Zero Maturity and M2 grow smartly during the recession

MZM and M2 are only minor parts of the money supply. To see the full power of the zero key, all forms of money need to be considered.

To fully stress test the output side of the zeros function, we viewed Fed borrowing displayed as a compound annual rate of change since 1919 and see that the 3.1 sextillion percent rise shows the Fed’s zero generating capacity fully intact.

No zeros shortage here

Our joke, admittedly overwrought, is that nothing prevents the Fed from expanding government credit or the money supply to compensate for any deficiency in money and credit creation in the private credit markets.

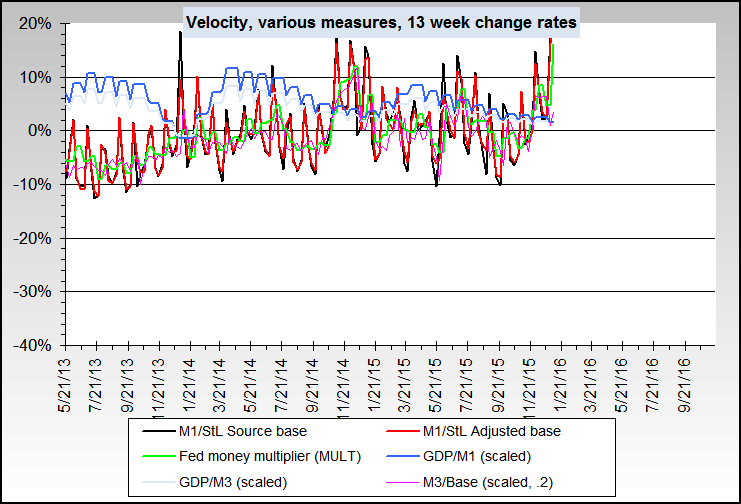

Once past this first part of the deflationista's argument, the next is the "you take a horse to water but can't make him drink" argument, that the Fed can create all the money in the world but it can't make households and businesses spend it. The key measure of how much money is getting spent is the velocity of money. Arguably, velocity slowed since the Q4 2008 period of deleveraging, but here too the Fed is making "progress," if that is the word.

Time and again, an increase in the money supply eventually expresses itself as higher prices. But the Fed can also draw that money supply down in the future, to lower inflation. The bond markets have been betting that it can, and will, until recently.

This modest recent shift away from treasury bonds has been widely reported as signalling an increased appetite for risk. Alternatively, it may signal increased concern about future inflation.

The Fed can expand its balance sheet virtually infinately to increase the money supply to avert a deflation spiral that the deflationistas expect, and can reverse the process to avert an inflation spiral in the future that the hyperinflationsitas expect. What the Fed and Treasury cannot do, however, is increase the purchasing power of the money created, regardless of quantity, or the creditworthiness of the US. These are only earned by sound fiscal, economic, and trade policy, and here the US, in the name of fighting a short term crisis, is heading in the wrong direction, with stimulus programs without a clear return on investment, and spending commitments that bring the nation's global credit limit into question.

For a nation with so much internal and external debt, inflation is not only possible but also the most politically convenient outcome in the long run, and one that the current structure of debt allows without the exertion of political will to deal with the debt in a way that diffuses the growing conflicts of interest between debtors and creditors as the crises deepens.

iTulip Select: The Investment Thesis for the Next Cycle™

__________________________________________________

To receive the iTulip Newsletter or iTulip Alerts, Join our FREE Email Mailing List

Copyright © iTulip, Inc. 1998 - 2009 All Rights Reserved

All information provided "as is" for informational purposes only, not intended for trading purposes or advice. Nothing appearing on this website should be considered a recommendation to buy or to sell any security or related financial instrument. iTulip, Inc. is not liable for any informational errors, incompleteness, or delays, or for any actions taken in reliance on information contained herein. Full Disclaimer

Comment