Today we're offered by Yahoo! Finance what passes currently for mainstream financial press advice on matters of personal credit. This Quick Comment is directed mostly to our younger readers.

The reason is that a car, unlike a home, is a rapidly depreciating asset. A house is not a depreciating asset, and so is a better–but still not a good–use of credit, long term. As Professor Robert Shiller points out in Irrational Exuberance: Second Edition , a house appreciates at a rate more or less equal to the rate of inflation, except during real estate bubbles, the topic of his book. That means you will not realize real gains on your "investment" in a house over the long term. From a depreciation standpoint, a house is a "neutral asset," although there are a lot of costs involved in maintaining the value of property that most real estate sales people don't like to talk about. (No, precious metals don't earn interest, but you don't have to mow and water the lawn or paint them every few years either.) But whereas the price of a house at least more or less keeps up with inflation, a new car depreciates around 20% instantaneously when you drive it off the lot. The only exception to this during a dollar depreciation and you happen to have bought a car exported by a country that has a currency that's appreciating relative to the dollar.

, a house appreciates at a rate more or less equal to the rate of inflation, except during real estate bubbles, the topic of his book. That means you will not realize real gains on your "investment" in a house over the long term. From a depreciation standpoint, a house is a "neutral asset," although there are a lot of costs involved in maintaining the value of property that most real estate sales people don't like to talk about. (No, precious metals don't earn interest, but you don't have to mow and water the lawn or paint them every few years either.) But whereas the price of a house at least more or less keeps up with inflation, a new car depreciates around 20% instantaneously when you drive it off the lot. The only exception to this during a dollar depreciation and you happen to have bought a car exported by a country that has a currency that's appreciating relative to the dollar.

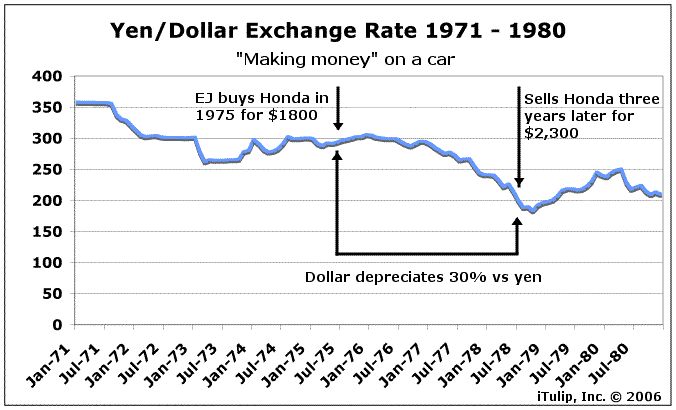

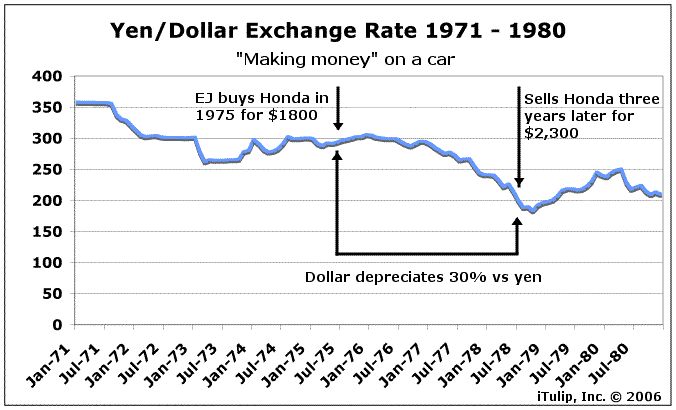

For example, I purchased a Honda Civic in 1975 for $1,800 and sold it in 1978–to help pay for college–for $2,300.

Nice! I "felt" like I was making money, on a car I bought new, no less, the most notoriously money-losing, rapidly depreciating major purchase a person can make. At the early stage of an inflation, everyone thinks they're getting richer, as nominal incomes rise along with interest rates on CDs and other short term interest bearing securities. The problem is that in nominal, that is, inflation-adjusted terms, the purchasing power of these securities is declining. Once the average person realized that, which they did around the year I sold that Honda, and it looked like the government lacked the political will to tackle the inflation problem, the rush to hard assets and the gold bubble got going.

Currency re-valuation is one of many stupid pet tricks that governments backed into a corner cause economies to do. We are assured, of course, that that can never happen again–a dollar depreciation and inflation to lighten the U.S. foreign debt load, which is why governments re-value currencies. We shall see. But that's an unusual case. Usually, cars depreciate both in nominal and in real terms. Back to our topic: using credit to finance depreciating assets.

There are two kinds of transactions: cash and credit. The amount of cash you have depends on your past actual savings rate relative to your income and expenses. The amount of credit you have depends on your future potential savings rate relative to your future income and expenses. Thus your credit is as mutable as your savings, that is, it goes up and down over time depending on your circumstances, although the "balance" in your "credit account" is not as apparent as the balance–or lack of balance–in your cash account. Your "credit account" balance can also go up and down based on circumstances beyond your control, such as a credit squeeze in the markets, as typically happens after credit cycles top. For now, let's stick to matters you can control.

If you take a hit on your income, your expenses spike, or you take out a big loan, the amount in your "credit account" declines. Most importantly, unlike a cash transaction, a credit transaction results in a debt. A debt is a lien on future labor; and you derive most of your income from your labor. So, you never, ever want to put a lien on your future labor except for the purpose of investing in an asset that is likely to increase in value over the life of the loan, that is, to exceed to total cost of the principle plus interest on the loan.

To do otherwise is to discount the value of your labor. When you use your credit to purchase a product–a depreciating asset by definition because it will always be worth less later–you are taking a portion of your future income and spending it on a product that you could otherwise have purchased in the future with savings–plus the interest paid on your savings–at a lower cost. (The loss in purchasing power of savings due to inflation while you save to buy with cash versus paying today with credit is a wash because the same number of dollars will buy more car in a few years, as has been the case since cars were invented.) So, when you purchase a product like a car on credit you are losing out on both the total price you are paying (principle plus interest) and the loss of interest income on your savings if you had saved up to buy a car with cash in the future instead. I think your future labor is worth a lot, and hope you do, too. You owe it to yourself to not devalue your future labor.

Since a car is a depreciating asset, the correct answer to the question, "How Much of Your Car Should You Finance?" then is zero. You can "afford" the car you can buy with cash. There is one exception, and that's the zero interest rate loan. If you buy a car that qualifies–usually the least desirable cars–and you qualify, that's almost like buying a car with cash. The loan will consume some of your credit, and will be offered by most dealers at a lower price if you buy with cash, but at least you're not also putting an interest lien on your future income, and you are freeing up cash to use for other purposes where you might be tempted to use credit, such as meals and holiday presents. A meal, obviously, depreciates very quickly in your stomach, after which its value is about equal to your average economist's economic forecast.

Yours truly has not always purchased cars this way. I leased a car for a year at very high rates when I was young and had just I experienced a big jump in income. I was feeling flush. So I understand what leads to these decisions, from time to time. And, yes, life is short, so live it up. But in the long run, the continuous practice of using your credit–devaluing your future labor–is the habit of buying into a system that, not happy to take your income only in the form of taxes, has set up government sponsored institutions like the Fannie Mae to separate you from your future income as well.

"But there are tax advantages to holding a mortgage," you say. The government raises a tax on your current income via an income tax, then offers to partially reduce it if you accept a tax on your future income via interest on a government sponsored loan to buy a house that bearly keeps up with the rate of inflation–except during a housing bubble, such as we just experienced. This is what passes for good household finance? How long have North Americans been falling for this nonsense?

"But I can't afford any car I can pay for with with cash–I don't have any cash–and I need a car to get to work," you say. You're not alone. Americans have been falling for the bad idea of purchasing depreciating or neutral assets with credit for so long that they no longer save. The Frankenstein Economy encourages them to see their credit not as finite, like their savings, but as a bottomless well: there's always another loan coming, more credit to be extended.

In the recent words of and FOMC vice-chairman Gerald Corrigan, "very creative financial services companies" offer financial products to foreign investors, which investment results in a constant expansion of U.S. credit available to U.S. citizens."

In the same breath, he says that his big worry is U.S. savings rates: “The first point I would make is related somewhat to the one Bill just made–its kind of the other side of it. That is that the United States savings rate is virtually zero. The household saving rate is negative. And for the reasons that Bill mentioned and a whole bunch of other reasons as well, this is a potentially very dangerous situation, not only in terms of economic and financial terms, but it brings with it, I think, some potentially very serious problems down the road in terms of the well being of our own citizens."

Somehow Corrigan hasn't put these two ideas together. Idea one, that "very creative financial services companies" offer foreign investors products that have led to the "potentially very dangerous situation" with, idea two, that the "United States savings rate that is virtually zero."

Just because he's confused, doesn't mean you need to be.

The practical answer for anyone who needs a car to get to work but has little cash is to buy the cheapest used car you can tolerate–a shitbox, to be precise–take out as small a loan as possible, and drive it proudly as symbol of your understanding of the principle "don't buy depreciating assets with credit" and of your unwillingness to knuckle under and discount the value of your future labor by putting a lien on it to purchase an overpriced car from a bank.

The shitbox: New symbol of self-worth?

How Much of Your Car Should You Finance?

November 20, 2006 (Yahoo! Finance)

Kicking a few tires is only half the battle. Before you begin looking for a new car, you should know your limits and what you should be spending. Experts say you shouldn't spend more than 10 percent of your gross income on car expenses, which includes the cost of the car along with insurance, gas and maintenance.

Once you decide on a price range, you'll want to decide how much you can put down as a down payment and then negotiate the price of your car. Too many buyers accept long financing arrangements in order to minimize their down payment. If they decide to trade the car in the first year or so, they often find that they actually owe more on their car than it's worth. A good rule of thumb is never to finance more than 80 percent of the true cost---the dealer's invoice---of the car. At least 20 percent or more should be paid in cash or the equity of your trade.

If "experts" advise a person to spend no more than 10% of gross income on financing and other auto costs annually then "experts" are wrong. The correct answer to the question, "How Much of Your Car Should You Finance?" is: zero percent.November 20, 2006 (Yahoo! Finance)

Kicking a few tires is only half the battle. Before you begin looking for a new car, you should know your limits and what you should be spending. Experts say you shouldn't spend more than 10 percent of your gross income on car expenses, which includes the cost of the car along with insurance, gas and maintenance.

Once you decide on a price range, you'll want to decide how much you can put down as a down payment and then negotiate the price of your car. Too many buyers accept long financing arrangements in order to minimize their down payment. If they decide to trade the car in the first year or so, they often find that they actually owe more on their car than it's worth. A good rule of thumb is never to finance more than 80 percent of the true cost---the dealer's invoice---of the car. At least 20 percent or more should be paid in cash or the equity of your trade.

The reason is that a car, unlike a home, is a rapidly depreciating asset. A house is not a depreciating asset, and so is a better–but still not a good–use of credit, long term. As Professor Robert Shiller points out in Irrational Exuberance: Second Edition

, a house appreciates at a rate more or less equal to the rate of inflation, except during real estate bubbles, the topic of his book. That means you will not realize real gains on your "investment" in a house over the long term. From a depreciation standpoint, a house is a "neutral asset," although there are a lot of costs involved in maintaining the value of property that most real estate sales people don't like to talk about. (No, precious metals don't earn interest, but you don't have to mow and water the lawn or paint them every few years either.) But whereas the price of a house at least more or less keeps up with inflation, a new car depreciates around 20% instantaneously when you drive it off the lot. The only exception to this during a dollar depreciation and you happen to have bought a car exported by a country that has a currency that's appreciating relative to the dollar.

, a house appreciates at a rate more or less equal to the rate of inflation, except during real estate bubbles, the topic of his book. That means you will not realize real gains on your "investment" in a house over the long term. From a depreciation standpoint, a house is a "neutral asset," although there are a lot of costs involved in maintaining the value of property that most real estate sales people don't like to talk about. (No, precious metals don't earn interest, but you don't have to mow and water the lawn or paint them every few years either.) But whereas the price of a house at least more or less keeps up with inflation, a new car depreciates around 20% instantaneously when you drive it off the lot. The only exception to this during a dollar depreciation and you happen to have bought a car exported by a country that has a currency that's appreciating relative to the dollar. For example, I purchased a Honda Civic in 1975 for $1,800 and sold it in 1978–to help pay for college–for $2,300.

Nice! I "felt" like I was making money, on a car I bought new, no less, the most notoriously money-losing, rapidly depreciating major purchase a person can make. At the early stage of an inflation, everyone thinks they're getting richer, as nominal incomes rise along with interest rates on CDs and other short term interest bearing securities. The problem is that in nominal, that is, inflation-adjusted terms, the purchasing power of these securities is declining. Once the average person realized that, which they did around the year I sold that Honda, and it looked like the government lacked the political will to tackle the inflation problem, the rush to hard assets and the gold bubble got going.

Currency re-valuation is one of many stupid pet tricks that governments backed into a corner cause economies to do. We are assured, of course, that that can never happen again–a dollar depreciation and inflation to lighten the U.S. foreign debt load, which is why governments re-value currencies. We shall see. But that's an unusual case. Usually, cars depreciate both in nominal and in real terms. Back to our topic: using credit to finance depreciating assets.

There are two kinds of transactions: cash and credit. The amount of cash you have depends on your past actual savings rate relative to your income and expenses. The amount of credit you have depends on your future potential savings rate relative to your future income and expenses. Thus your credit is as mutable as your savings, that is, it goes up and down over time depending on your circumstances, although the "balance" in your "credit account" is not as apparent as the balance–or lack of balance–in your cash account. Your "credit account" balance can also go up and down based on circumstances beyond your control, such as a credit squeeze in the markets, as typically happens after credit cycles top. For now, let's stick to matters you can control.

If you take a hit on your income, your expenses spike, or you take out a big loan, the amount in your "credit account" declines. Most importantly, unlike a cash transaction, a credit transaction results in a debt. A debt is a lien on future labor; and you derive most of your income from your labor. So, you never, ever want to put a lien on your future labor except for the purpose of investing in an asset that is likely to increase in value over the life of the loan, that is, to exceed to total cost of the principle plus interest on the loan.

To do otherwise is to discount the value of your labor. When you use your credit to purchase a product–a depreciating asset by definition because it will always be worth less later–you are taking a portion of your future income and spending it on a product that you could otherwise have purchased in the future with savings–plus the interest paid on your savings–at a lower cost. (The loss in purchasing power of savings due to inflation while you save to buy with cash versus paying today with credit is a wash because the same number of dollars will buy more car in a few years, as has been the case since cars were invented.) So, when you purchase a product like a car on credit you are losing out on both the total price you are paying (principle plus interest) and the loss of interest income on your savings if you had saved up to buy a car with cash in the future instead. I think your future labor is worth a lot, and hope you do, too. You owe it to yourself to not devalue your future labor.

Since a car is a depreciating asset, the correct answer to the question, "How Much of Your Car Should You Finance?" then is zero. You can "afford" the car you can buy with cash. There is one exception, and that's the zero interest rate loan. If you buy a car that qualifies–usually the least desirable cars–and you qualify, that's almost like buying a car with cash. The loan will consume some of your credit, and will be offered by most dealers at a lower price if you buy with cash, but at least you're not also putting an interest lien on your future income, and you are freeing up cash to use for other purposes where you might be tempted to use credit, such as meals and holiday presents. A meal, obviously, depreciates very quickly in your stomach, after which its value is about equal to your average economist's economic forecast.

Yours truly has not always purchased cars this way. I leased a car for a year at very high rates when I was young and had just I experienced a big jump in income. I was feeling flush. So I understand what leads to these decisions, from time to time. And, yes, life is short, so live it up. But in the long run, the continuous practice of using your credit–devaluing your future labor–is the habit of buying into a system that, not happy to take your income only in the form of taxes, has set up government sponsored institutions like the Fannie Mae to separate you from your future income as well.

"But there are tax advantages to holding a mortgage," you say. The government raises a tax on your current income via an income tax, then offers to partially reduce it if you accept a tax on your future income via interest on a government sponsored loan to buy a house that bearly keeps up with the rate of inflation–except during a housing bubble, such as we just experienced. This is what passes for good household finance? How long have North Americans been falling for this nonsense?

"But I can't afford any car I can pay for with with cash–I don't have any cash–and I need a car to get to work," you say. You're not alone. Americans have been falling for the bad idea of purchasing depreciating or neutral assets with credit for so long that they no longer save. The Frankenstein Economy encourages them to see their credit not as finite, like their savings, but as a bottomless well: there's always another loan coming, more credit to be extended.

In the recent words of and FOMC vice-chairman Gerald Corrigan, "very creative financial services companies" offer financial products to foreign investors, which investment results in a constant expansion of U.S. credit available to U.S. citizens."

In the same breath, he says that his big worry is U.S. savings rates: “The first point I would make is related somewhat to the one Bill just made–its kind of the other side of it. That is that the United States savings rate is virtually zero. The household saving rate is negative. And for the reasons that Bill mentioned and a whole bunch of other reasons as well, this is a potentially very dangerous situation, not only in terms of economic and financial terms, but it brings with it, I think, some potentially very serious problems down the road in terms of the well being of our own citizens."

Somehow Corrigan hasn't put these two ideas together. Idea one, that "very creative financial services companies" offer foreign investors products that have led to the "potentially very dangerous situation" with, idea two, that the "United States savings rate that is virtually zero."

Just because he's confused, doesn't mean you need to be.

The practical answer for anyone who needs a car to get to work but has little cash is to buy the cheapest used car you can tolerate–a shitbox, to be precise–take out as small a loan as possible, and drive it proudly as symbol of your understanding of the principle "don't buy depreciating assets with credit" and of your unwillingness to knuckle under and discount the value of your future labor by putting a lien on it to purchase an overpriced car from a bank.

The shitbox: New symbol of self-worth?

The paradox is that if you do this, you are more likely to wind up in a position to afford a really great car some day from savings, because you will not have squandered your future income by buying depreciating assets with credit.

iTulip Select: The Investment Thesis for the Next Cycle™

_____

To buy and trade gold easily and inexpensively, see BullionVault

To receive the iTulip Newsletter or iTulip Alerts, Join our FREE Email Mailing List

Copyright © iTulip, Inc. 1998 - 2006 All Rights Reserved

All information provided "as is" for informational purposes only, not intended for trading purposes or advice. Nothing appearing on this website should be considered a recommendation to buy or to sell any security or related financial instrument. iTulip, Inc. is not liable for any informational errors, incompleteness, or delays, or for any actions taken in reliance on information contained herein. Full Disclaimer

iTulip Select: The Investment Thesis for the Next Cycle™

_____

To buy and trade gold easily and inexpensively, see BullionVault

To receive the iTulip Newsletter or iTulip Alerts, Join our FREE Email Mailing List

Copyright © iTulip, Inc. 1998 - 2006 All Rights Reserved

All information provided "as is" for informational purposes only, not intended for trading purposes or advice. Nothing appearing on this website should be considered a recommendation to buy or to sell any security or related financial instrument. iTulip, Inc. is not liable for any informational errors, incompleteness, or delays, or for any actions taken in reliance on information contained herein. Full Disclaimer

Comment