Productivity or Credit? What's Driving Economic Growth?

August 20, 2006

As a fresh recession looms, debate that's been going on for years on the nature of productivity growth is coming to a head.

On one side of the 2001 - 2005 US productivity "miracle" argument are those that say computers have made us all more efficient. On the other side of the argument are guys like Prof Gordon of Northwestern who, "...puts greater weight on the natural limits to an 'explosion' of brutal corporate cost-cutting following the bursting of the stock market bubble. These productivity increases, he argues. were not really caused by IT, even though they were in part enabled by it."

This latter view conforms to experience. Most readers can attest that until recently, the productivity miracle appeared to result from firms laying off a lot of workers and demanding that the remaining workers either pick up extra duties from the folks in the unemployment line... or join them, and for a long time. The period also happened to be one of the few when getting sacked meant staying out of work for a long time. Not since the near depression conditions of the 1980 to 1983 recessions has the median duration of unemployment been so high as it was between 2000 and 2003.

There are two challenges in determining the influence of producitivity growth to economic growth during the 2001 to 2006 productivity "miracle" period.

First, we don't know how to measure it. This is put well by William Poole, President, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis back in 1999:

Perhaps the mystery of slow productivity growth in the 1970s and the rise in credit and productivity growth that followed may be solved by the hypothesis that the two are related. They sure look that way. I call your attention to two periods of apparent correlation between productivity and bank credit, blips with a six month time lag in 2001 and 2003 in the Chart 3 below.

Is what is measured as "productivity" a function of bank credit or the other way around?

In any case, whether working better due to computers, working harder with the threat of long term unemployment hanging over workers' heads, miscalculation of the measure of productivity itself, or the fact that what we are measuring as "productivity" may be a product of expanded credit, it's reasonable to worry that the so-called US productivity "miracle" may be a one time, non-repeatable event. Productivity increases from layoffs produce declining marginal returns on labor as labor is further reduced; when unemployment declines, so may productivity. Computer systems also do not continuously improve productivity but tend to do so dramatically when they are introduced and contribute incrementally to productivity thereafter. Finally, if what is measured as productivity has become highly correlated to bank credit, it follows that a decline in one may accompany a decline in the other, and both are at all time highs.

Join our FREE Email Mailing List

Copyright © iTulip, Inc. 1998 - 2006 All Rights Reserved

All information provided "as is" for informational purposes only, not intended for trading purposes or advice. Nothing appearing on this website should be considered a recommendation to buy or to sell any security or related financial instrument. iTulip, Inc. is not liable for any informational errors, incompleteness, or delays, or for any actions taken in reliance on information contained herein. Full Disclaimer

August 20, 2006

As a fresh recession looms, debate that's been going on for years on the nature of productivity growth is coming to a head.

Economic juggernaut may face lower speed limit

Aug 17, 2006 (MSNBC)

The US productivity "miracle" – one of the defining economic developments of modern times – is looking a shade less miraculous than it did a month ago.

Following a series of revisions to recent historic data, economists are pondering whether to reduce their estimates of the speed at which the world's biggest economy can grow without generating inflation. Many have done so already, cutting their assessments of US potential growth by about 0.25 per cent. This may not sound a lot but, compounded year after year, it adds up to a significant loss.

In many ways, the truly remarkable part of the productivity miracle began in 2001, when the dotcom bubble burst. Rather than slow down, as in past downturns, US productivity growth accelerated as companies squeezed greater output from bubble-era investments – and continued to do so as growth picked up.

"Looking back at the late 1990s, it was more of an investment boom and less of a productivity story than we thought at the time," says Bart an Ark, a professor at Groningen university in the Netherlands and director of international economic research at the US Conference Board. "From 2001 onwards it is not an investment story – it is a productivity story."

Productivity is the measure of economic output per unit labor. Here's the chart since 1958, recessions in pink.Aug 17, 2006 (MSNBC)

The US productivity "miracle" – one of the defining economic developments of modern times – is looking a shade less miraculous than it did a month ago.

Following a series of revisions to recent historic data, economists are pondering whether to reduce their estimates of the speed at which the world's biggest economy can grow without generating inflation. Many have done so already, cutting their assessments of US potential growth by about 0.25 per cent. This may not sound a lot but, compounded year after year, it adds up to a significant loss.

In many ways, the truly remarkable part of the productivity miracle began in 2001, when the dotcom bubble burst. Rather than slow down, as in past downturns, US productivity growth accelerated as companies squeezed greater output from bubble-era investments – and continued to do so as growth picked up.

"Looking back at the late 1990s, it was more of an investment boom and less of a productivity story than we thought at the time," says Bart an Ark, a professor at Groningen university in the Netherlands and director of international economic research at the US Conference Board. "From 2001 onwards it is not an investment story – it is a productivity story."

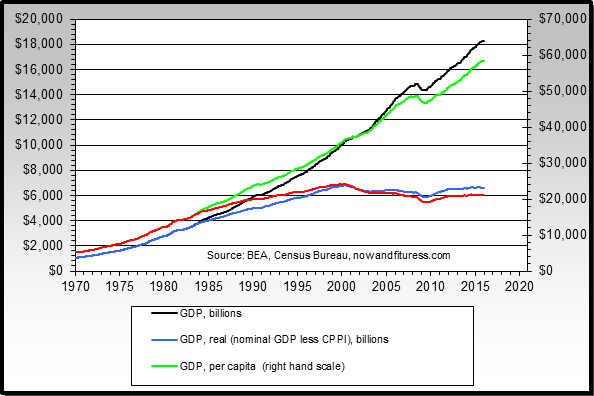

Chart 1

One way to increase productivity is to use more machines to make workers more efficient. Another way is to reduce the number of workers but keep output growing. On one side of the 2001 - 2005 US productivity "miracle" argument are those that say computers have made us all more efficient. On the other side of the argument are guys like Prof Gordon of Northwestern who, "...puts greater weight on the natural limits to an 'explosion' of brutal corporate cost-cutting following the bursting of the stock market bubble. These productivity increases, he argues. were not really caused by IT, even though they were in part enabled by it."

This latter view conforms to experience. Most readers can attest that until recently, the productivity miracle appeared to result from firms laying off a lot of workers and demanding that the remaining workers either pick up extra duties from the folks in the unemployment line... or join them, and for a long time. The period also happened to be one of the few when getting sacked meant staying out of work for a long time. Not since the near depression conditions of the 1980 to 1983 recessions has the median duration of unemployment been so high as it was between 2000 and 2003.

Chart 2

How's that for motivation to put out something extra for the boss?There are two challenges in determining the influence of producitivity growth to economic growth during the 2001 to 2006 productivity "miracle" period.

First, we don't know how to measure it. This is put well by William Poole, President, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis back in 1999:

"Productivity growth is a terribly important subject for the United States, indeed for every country. But this is not an easy subject. The puzzles of the 1970s slowdown in productivity growth have not been resolved. The puzzles of the 1990s increase in productivity growth seem only to deepen with further research into what is going on. It is amazing, but still a fact at this time, that most of the reported increase in productivity growth can be attributed to the computer-producing industry and little to the computer-using industries--that is, the whole rest of the economy."

"To understand just how amazing this puzzle is, I'll put the point this way: All, or most--depending on your choice of expert--of the increase in productivity growth for the entire U.S. economy can be attributed to a single industry--computer manufacturing--that amounts to about 1¼ percent of the economy! That is a truly remarkable finding, and it really doesn't matter much whether the truth is 'all' or "most."

Second, the biggest challenge in asserting that productivity has been the primary economic growth driver during the 2001 to 2006 period is that this factor has to be measured against the impact of credit growth. While productivity was reported as growing by approximately 20% over the period (see Chart 1 above), credit and debt growth grew much more dramatically: "Compared with an increase by $827 billion in 2000, credit and debt growth has quadrupled. Total outstanding indebtedness rose to $41.8 trillion, equal to 334% of nominal GDP and 376% of real GDP. In the first quarter, $4.30 of additional debt was added for each dollar added to nominal GDP growth and $7.50 additional debt for each dollar added to real GDP growth. Until the late 1970s, this credit-to-GDP ratio had held at a steady rate of 1:1.4 for over 30 years." "To understand just how amazing this puzzle is, I'll put the point this way: All, or most--depending on your choice of expert--of the increase in productivity growth for the entire U.S. economy can be attributed to a single industry--computer manufacturing--that amounts to about 1¼ percent of the economy! That is a truly remarkable finding, and it really doesn't matter much whether the truth is 'all' or "most."

Perhaps the mystery of slow productivity growth in the 1970s and the rise in credit and productivity growth that followed may be solved by the hypothesis that the two are related. They sure look that way. I call your attention to two periods of apparent correlation between productivity and bank credit, blips with a six month time lag in 2001 and 2003 in the Chart 3 below.

Chart 3

Is what is measured as "productivity" a function of bank credit or the other way around?

In any case, whether working better due to computers, working harder with the threat of long term unemployment hanging over workers' heads, miscalculation of the measure of productivity itself, or the fact that what we are measuring as "productivity" may be a product of expanded credit, it's reasonable to worry that the so-called US productivity "miracle" may be a one time, non-repeatable event. Productivity increases from layoffs produce declining marginal returns on labor as labor is further reduced; when unemployment declines, so may productivity. Computer systems also do not continuously improve productivity but tend to do so dramatically when they are introduced and contribute incrementally to productivity thereafter. Finally, if what is measured as productivity has become highly correlated to bank credit, it follows that a decline in one may accompany a decline in the other, and both are at all time highs.

Join our FREE Email Mailing List

Copyright © iTulip, Inc. 1998 - 2006 All Rights Reserved

All information provided "as is" for informational purposes only, not intended for trading purposes or advice. Nothing appearing on this website should be considered a recommendation to buy or to sell any security or related financial instrument. iTulip, Inc. is not liable for any informational errors, incompleteness, or delays, or for any actions taken in reliance on information contained herein. Full Disclaimer

Comment