Ka-Poom Theory Update Two – Part I: Bang or a whimper

What would Robert Triffin (1910 - 1993) say about Ka-Poom Theory? This two part section of our multi-part Ka-Poom Theory Update Two series delve into the works of Belgian economist Robert Triffin. We summarize his in-depth critique of the international monetary system (IMS), his vision for a workable alternative in the 1960s and 1970s, and exhaustively quote and comment on his long-lost and forgotten final book, "IMS: International Monetary System or Scandal?" That book includes petulant protests penned in the final years of his life in the early 1990s as he observed the danger of an epic monetary crisis growing yet ignored by the international central banking community. He became disillusioned with “powerful politicians” and “special interests” that in his opinion thwarted IMS reform efforts for decades, reforms urgently needed to avert catastrophe. A fresh global monetary crisis has been building for 20 years since his last warning in 1992 a year before his death. Imbalances in the IMS have reached a breaking point over the years following the American Financial Crisis, and Triffin's analysis or the problem and his admonitions are more relevant than ever.

CI: Before we get to Triffin, how does the euro crisis relate to your Ka-Poom Theory? Is austerity for Greece and Spain the right solution? What would Triffin say?

EJ: You could say Triffin predicted Europe’s current crisis. In a rush to isolate and protect Europe from a usurious and dangerous US-centric IMS, Europe failed to get the structure right.

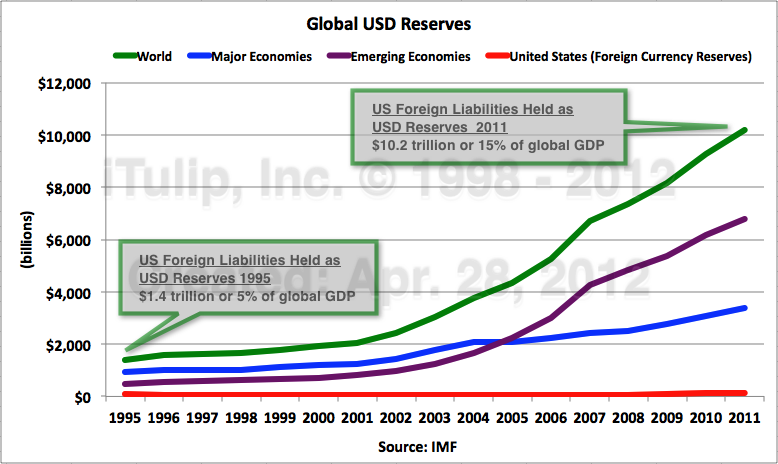

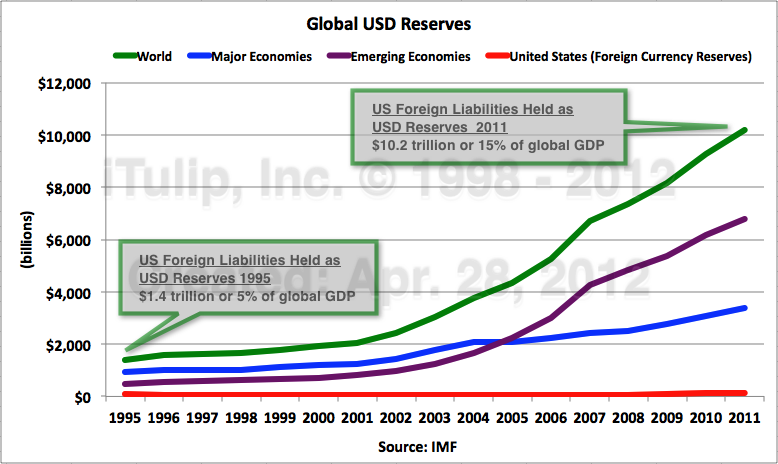

We got our hands on the last book Triffin published in 1992, a year before his death, provocatively titled "IMS: International Monetary System or Scandal?" It was published only in Europe by a relatively obscure organization, The European Policy Unit at the European University Institute. In it Triffin complains that IMS reforms were agreed to by the majority of major powers in 1974 but these were repeatedly vetoed by the US and UK. As a consequence of decades of delay, he warned that accumulated USD liabilities threatened the world economy with a currency crisis of epic proportions. That was 20 years ago when liabilities look quaint compared to 2012 levels.

US Dollars held as currency reserves at the time of Triffin’s 1992 warning increased 300% relative to global GDP by 2011.

CI: Briefly, who is Robert Triffin?

EJ: Belgian economist Robert Triffin predicted in 1959 that the Bretton Woods monetary system of currencies fixed to the dollar and redeemable in gold was doomed, which forecast proved accurate in 1971 when the Nixon administration ended gold redeem-ability. Below is a video of French President Charles de Gaulle echoing Triffin's concerns in 1965 and calling for reform.

After 1971 the IMS became based on a U.S. Treasury bond standard, that is, the debt-based fiat currency of the United States. Currencies then “floated” relative to each other. In practice that meant that rather than governments buying and selling currency to influence the quantity and thus the price of a currency to maintain exchange rates in a narrow band of less than 1%, governments allowed exchange rates to rise and fall with market demand, intervening only in times of crisis.

CI: Did Triffin anticipate the euro?

EJ: Triffin had a very clear vision of how a European currency needed to operate and was a proponent of a European central bank. He believed that first and foremost the point of a European currency was to insulate Europe from the disadvantages and unseemly risks posed by the US dollar based IMS that Charles de Gaulle refereed to as the "exorbitant privilege." In his words, “It [the euro] would, first of all, enable the monetary authorities of a United Europe to sterilize in the form of “consols” the vast overhang of short-term dollar indebtedness inherited from former US balance~of-payments deficits and threatening at any time a collapse of the dollar on the world exchange markets.”

CI: That was in 1992? Did Europe get the euro Triffin wanted?

EJ: No, it got half a currency. Europe wasn’t politically ready for a whole currency. To have a whole currency a complete set of institutions and mechanisms is needed to ensure, in Triffin’s words, “the harmonization of budgetary and monetary policies indispensable to the irrevocable stabilization of exchange rates.” In other words not only an institution to act as lender of last resort and maintain inflation but a federal European tax and budgetary authority to prevent “excessive or persistent financing of the countries in deficit by the countries in surplus.” He warned that if the euro was not so structured, “Germany runs the risk of becoming the ‘milch cow’ (vache à lait) of inflationary Community members.” And so it was.

CI: Triffin famously predicted the collapse of the international gold standard. Now we can say he predicted the euro’s present troubles?

EJ: The 1992 book is a goldmine of insights into the flaws in the IMS and their implications. That said, Triffin’s reform ideas had flaws of their own. He was kind of the George Soros of his day, with well-intentioned ideas about helping poor countries but with heavy government action (read: spending) to achieve it. We’ll focus on him in Part II and quote his book extensively.

To answer your question on austerity for Greece and Spain, the euro was badly structured; in the wake of recession caused by the American Financial Crisis, Germany has become the milch cow of Greece and Spain, at least in the eyes of German voters, as was feared in the earliest days of euro planning. Germany’s leaders have to contend with a chorus of “I told you so” from early euro skeptics among Germany’s elite, and the majority opinion of a voting public that Greece needs to go through painful economic restructuring as Germany did after unification with East Germany in the early 1990s. Austerity for Greece is politically sensible but economically insane.

CI: How do you mean?

EJ: Austerity for Greece now means a reduction in government expenditure during the recession that was caused by the American Financial Crisis in 2008. Such a policy is the exact opposite of the one followed at the time by the country with the world’s largest external debt and the worst budget deficit as a percent of GDP when it was in recession in 2008, the United States. Imagine the largest lender to the US, China, demanding that the US tighten its belt and get it fiscal house in order in 2008 and 2009. Instead, China tripled its loans to the US from $400 billion to $1.2 trillion. China used the crisis to gain leverage. Within the political confines of the EU, Germany cannot be so strategic.

CI: What’s happened to Greece, then?

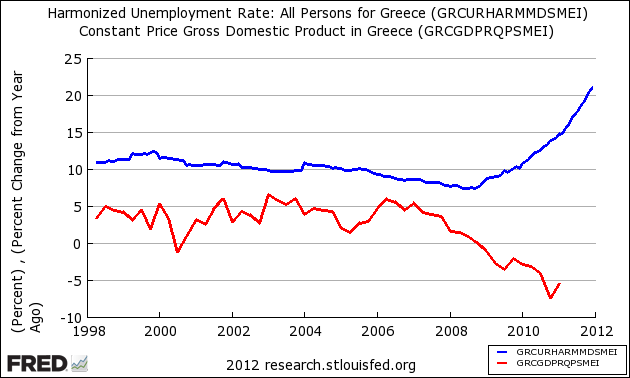

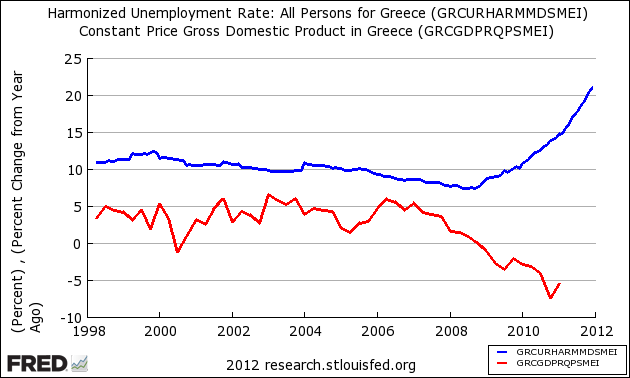

EJ: The predictable result of austerity during a recession, as you can see below, is even higher unemployment and even more rapidly shrinking output.

Unemployment and GDP rates in Greece after the recession caused by the American Financial Crisis

was followed up with austerity measures that worsened both.

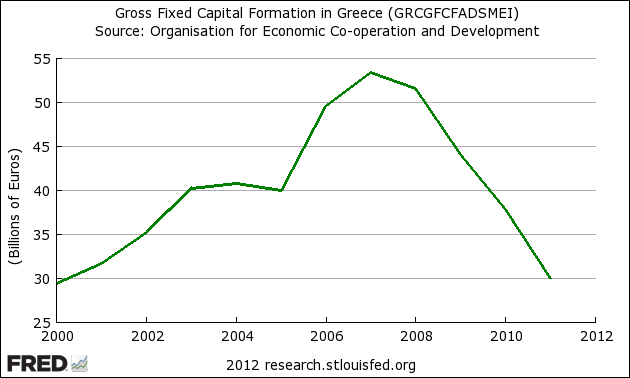

Obviously an economy that is shrinking is not growing its way out of debt.

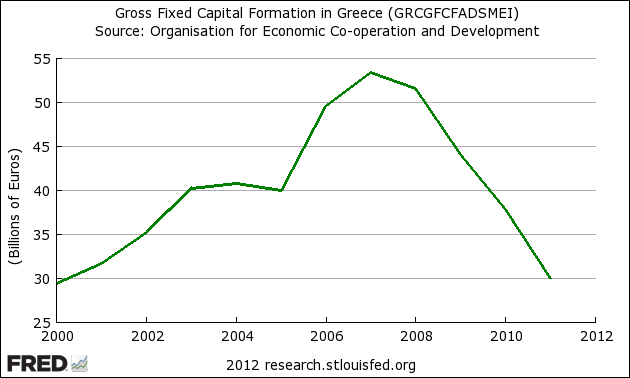

The whole point of austerity is ostensibly to increase savings. An economy that is not able to invest in its future capacity to grow – spend on plant and equipment versus consumption – will never, ever be able to grow its way out of debt. Austerity has sent Greece into a death spiral.

Investment in the future of the Greek economy has plummeted 43% from €53 billion in 2007

to €30 billion in 2011 annually.

CI: Why is austerity being imposed on Greece if the policy is making matters worse for creditors?

EJ: The perverse logic of the euro’s institutional framework created this ludicrous “solution” for Greece that makes political sense but no economic sense. The policy is the inevitable outcome of a mis-match of monetary institutions and political institutions of the currency union. A similar mismatch is bringing down the IMS as a whole, in my opinion.

CI: Playing devil’s advocate here. Why can’t Greece change its economy the way the US did in the 1980s after the tough austerity programs of 1979 to 1983? The US boomed for decades after those recessions.

EJ: In 1983 the US had little private sector debt compared to today. Debt had been inflated away over the previous decade. Also, the US had little public debt and no external debt to speak of. If the Fed tried doing today as the Fed did in the early 1980s and the US economy would first collapse into a deflationary recession then, if the crisis went unresolved by a fresh round of external demand for US debt, a hyperinflationary depression. The US economy lives on the edge of that precipice and has since 2008.

CI: So austerity has no chance of working in Greece?

EJ: By analogy, say you take out a mortgage from the bank to buy a house and the payments consume 50% of your income instead of 20% or 30% as is usual because the bank was greedy and more interested in maximizing the asset, your debt, than in guaranteeing a flow of payments should boom times not last forever. Then you borrow more to buy a car. Those payments consume another 10% of your income. You have three jobs to cover the debt payments and all of your other expenses. You can barely keep up. You economize. You don’t eat out. You wife cuts your hair. You cancel your cable service. Then recession hits. You lose one of your three jobs. Your income falls. You warn the bank that you may miss a payment. “No, no, no. We can’t have that,” says the loan officer. “We lent you more money that we should have but that’s your problem not ours. We analyzed your finances and here is our demand: You must sell your car so that you can afford to keep making mortgage payments to us.” And you say, “But if I sell my car I can’t get to one of the two jobs I have left. My income will fall even more! I’ll be less not better able to pay my mortgage.” To which the loan officer replies, “That’s not our problem. My boss says that’s the only way.” You reply, “Well how about forgiving the part of the mortgage that you should not have lent me in the first place?” To which the bank replies, “We are contractually entitled to the loan in full.”

CI: So what happens?

EJ: If you sell your car and lose one of your jobs. You are, as a result, forced to default on the mortgage. You invoke your homestead exemption, the US property owner’s equivalent of national sovereignty. Your credit rating goes to hell and the bank loses everything. But soon another bank is at your door trying to lend you money.

CI: Do you think that eventually Greece be forced to bolt the euro like an over-indebted homeowner defaulting on a mortgage and invoking the homestead exemption, i.e., default on euro debts and operate with full sovereignty?

EJ: I don't see it at this point. A safer bet is that it works out in whatever way is best for the strongest members of the system, Germany and France. The history of all currency and monetary systems is the history of strong countries imposing their will on the weak. The strong are the creditors. The weak are the debtors. It has always been so. If Germany was stupid enough to put itself in harm’s way by allowing Greece to take on debts it can’t repay, then it is both the weak and the strong who will suffer the consequences. Greece is a small country with no capacity to work its way out of debt in the short term. Among the world’s economies it ranks 37th in GDP and 33rd in GDP-per-capita. Its main industry is tourism. Watch for Greek politics to become more radicalized. Look for candidates to begin to run on platforms split along pro- and anti-European Union lines. If you start to hear the phrase "Greek sovereignty" used in campaign speeches, then it is time to start thinking about Greek exiting the euro.

CI: Are you saying Germany needs to write off more of the Greece’s debt? Isn’t the crisis also the fault of corrupt Greek government for failing to collect taxes from the Greek elite?

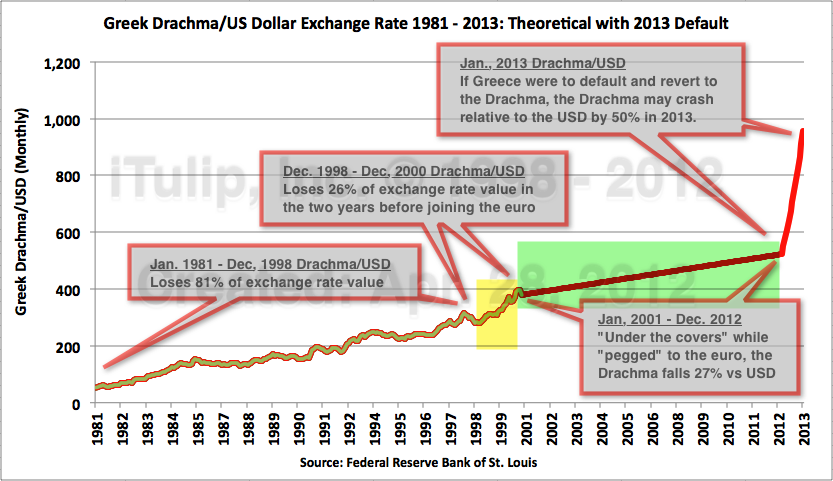

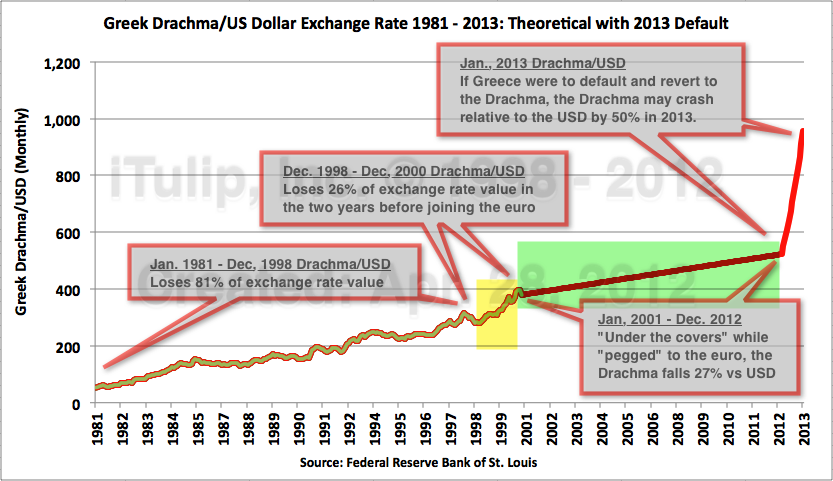

EJ: Fair point about Greece’s regressive tax policies, but it’s not like Germany has the moral high ground. German lenders knew perfectly well that Greece’s finances were awful and the Greek government was lying about its fiscal position. The Drachma fell 26% versus the dollar in the two years immediately before Greece joined the euro in Jan. 2000, a clear warning that Greece was unable to manage its finances in a way that markets found convincing. But in those days the US tech bubble economy was booming and the fever spread worldwide. No one in power was thinking about a future euro crisis. The euro as structured is fundamentally a glorified currency board. Germany went along with Greece joining the euro because Germany wanted Greece to buy German BMWs and German weapons. That was the quid pro quo. But that part of the calculation of blame is lsot on the German people; looking like the leader who allows Germany to be treated like a milch cow by Greece and Spain is politically untenable.

If Greece defaulted and left the euro in 2013, the Drachma/US Dollar exchange rate might look like this.

CI: What if Greece did revert to the Drachma?

EJ: Best case the Drachma continued to decline at the same rate "under the peg" so to speak, since 2000 as from 1998 to 2000, around 30% againts the USD. In an actual default where Greek euro denominated debt is repudiated, I estimate the Drachma quickly loses another 50% over a six to 12 month period. It would be devastating for Greece and for the entire euro system, which is why I think it will be averted and German cow will keep supplying milk.

CI: Why so bad for the rest of the euro zone?

EJ: Because the euro, without the institutions that the US has behind the dollar, has had to count on the commercial banks to bail out Green, Spain, and others to hold up the euro -- and China, too. That means the banks are largely capitalized with euro bonds. If the euro bonds issued by Greece go to zero, those of Italy and others fall, too. The banks become insolvent and you have a European financial crisis to rival the US version, but instead of worthless mortgage-backed securities you have worthless or nearly worthless sovereign debt.

CI: Does China’s leadership look weak with respect to its loans to the US the say you are saying the German leadership will if it didn't push Greece for austerity? The US has worse total balance sheet liabilities than Greece does. Why doesn't China press the US to clean up its fiscal house?

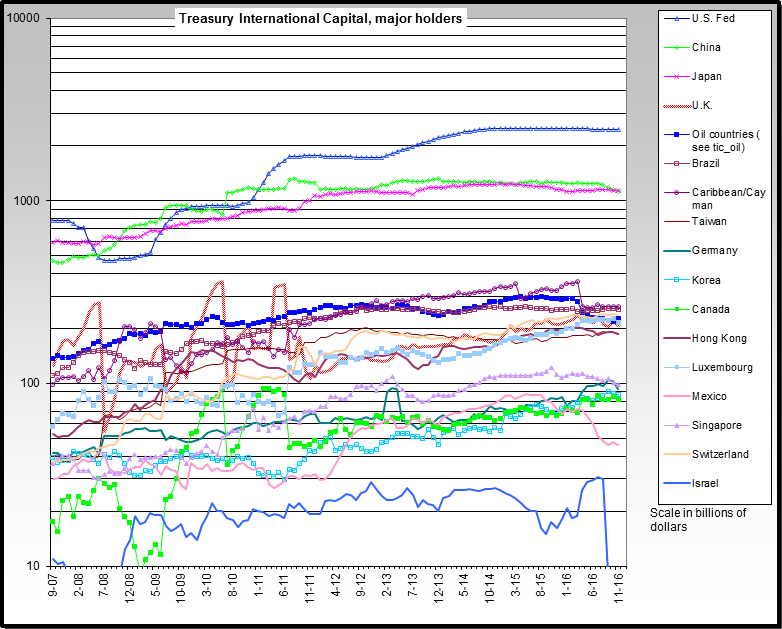

EJ: The US is not a tiny Mediterranean country with little to offer and on the verge of default. The US, unlike Greece, can always pay its debts by expanding its federal balance sheet. US creditors may not like the resulting loss in purchasing power of the principle and interest payments they receive but they full well know the alternative in the context of the operation of the IMS -- collapse. It is no accident that China stepped up to bail out the US from its self-inflicted disaster in 2008 and 2009. China ensured a continuation of an IMS that, while unfair, has allowed them to grow and stay in power, while also buying more chips to play to control US foreign policy that impacts China.

China increased its holdings of US Treasury bonds 300% from $400 billion before the American Financial Crisis

To $1,200 after. Japan increased holdings 30% from $600 billion to $900 billion.

Russia increased holdings 1,309% from $34 billion to $138 billion.

The composition of major foreign holders of US Treasury Bonds (UST) changed in 2008 with the American Financial Crisis. Countries that are not under the de factor American military protectorate, notably China and Russia, picked up a large part of the tab. I don’t think they will ever demand cold turkey austerity for the US. Unlike German leaders who have an election cycle to deal with, China’s leaders are strategic. China can apply pressure on the US to reduce spending where they want us to. For example they can get us to back off on confrontations over China’s “unfair” currency policies, to stay out of their way in Africa and Latin America, their inroads into the Middle East, and so on. My contacts in China suggest that this has been going on through political back channels for years. This is why you see, for example, major reductions in US military spending today, apparently out of nowhere when reductions in other areas will be more effective from the standpoint of reducing liabilities and improving the US fiscal position.

CI: You think China is cheating on the rimnimbi/dollar exchange rate?

EJ: The IMS has since 1971 been in principle a floating exchange rate system. Markets not governments determine exchange rates, although under the system governments can intervene to stabilize rates at the extremes. Every major country in the world abides this arrangement except for China. China maintains a peg to the dollar under 1% as was the arrangement for all countries under the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates. We in the US are in no position to complain. We owe China too much money.

CI: You paint a picture of a US that is already subservient to China.

EJ: If asked how much foreign debt is too much, the simple answer is this. Too much foreign debt is the amount that causes a nation to stop making political decisions in its own interest. The US passed that point with China long ago. We are no longer a sovereign nation in relation to to China. We are afraid to call China out on its mobster ruling class of the Chinese police state, a fact that becomes painfully obvious when on occasion a foreign national gets offed or a dissident's family is rounded and jailed. Going into debt to China will turn out to be the worst economic policy error in America’s history, right up there with the Argentine’s going into debt to the British in the 1850s -- it was all downhill from there. I can't think of a worse country to be in debt to.

CI: Is this a change to your Economic MAD theory from April 2006 when you said China and the US are bound by a balance of economic terror? You said, “China and the U.S. are running inter-dependent bubble economies, relying on the economic equivalent of Mutually Assured Destruction (M.A.D.) to keep one from blowing up the other’s economy. Whether by intent or accident, sooner or later market forces will assert themselves and both economies will go through tough transitions.” Still true?

EJ: My formulation made it to the highest levels of policy making in China, I’m told, and it’s still the most rational way to look at the underlying dynamics of the relationship. Over the years you have seen the idea picked up and discussed such as it is in the article: US-China: The Threat of Economic MAD. But much has happened since I came up with that way of looking at the relationship, notably the American Financial Crisis and the first Peak Cheap Oil crisis in 2008. China has gained the upper hand and they are starting to play it.

Ka-Poom Theory Update Two – Part II: The pigs get fat and the hogs get slaughtered ($ubscription)

CI: Does a Ka-Poom dollar and debt crisis have to happen?

EJ: We’re talking about a total foreign liability of $10.2 trillion in highly liquid USD currency reserves held by foreign central and commercial banks, mostly in U.S. Treasury bonds, plus $5 trillion in federal debt held by foreign individuals, institutions and governments, also as interest bearing U.S. Treasury bonds. I'll answer your question with three more: International USD reserves alone totaled 14% of global GDP as of Q4 2011. How is it possible that these liabilities have grown so large since de Gaulle’s and Triffin’s warnings? Did Triffin misunderstand how the IMS was going to develop? What will happen?

There are two scenarios, as I see it. Keep in mind that the liabilities themselves are a result of the US blocking reform for decades but that today it is the scale of the liabilities themselves that forms the primary obstacle to reform. To negotiate such a vast quantity of U.S. federal government liabilities away, the terms of the IMS that generated it over the past 40 years will have to be re-negotiated by three major monetary interest groups with widely differing interests and objectives and an unequal level of the power to get their way, one led by the US and the other two led by China -- although “led” is too strong a word. “Influenced” is a better word.

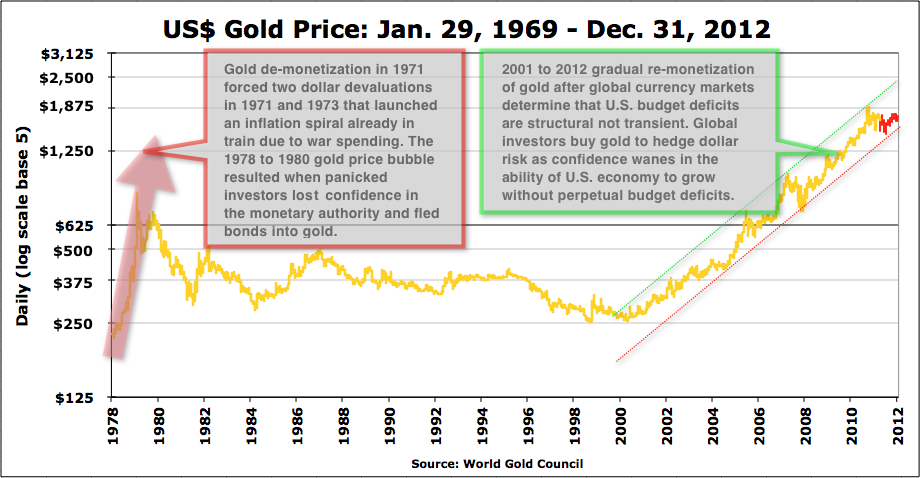

In the first Ka-Poom crisis scenario, this negotiation takes place under the duress, without an institutional framework designed to operate in such a crisis, and with the US doing everything in its power to maintain the status quo as we have for the past 40 years. Ka-Poom is a disorderly end to the IMS as in 1971 but without the US as a dominant power able to shove everyone else on the planet into line over the course of a decade until the system is working. In that scenario, if you thought the monetary chaos that produced the Great Inflation of the 1970s was bad, in the Ka-Poom scenario it’s ever nation for itself, and you’d better have a decent-sized gold reserve to stay in the global trade game. In that scenario, Treasury bond yields rise into double digits and the dollar exchange rate falls to $5000 per ounce of gold or worse.

CI: Worse? $5000 gold sounds good to me!

EJ: But it isn't. If you own gold you really want the second scenario, the less dramatic "bleed them out" scenario as China and her allies work the system to marginalize the US over decades. You may still get to $5000 gold but without the unseemly political chaos and financial hardship that billions of people would endure, including friends and family.

In the “bleed them out” scenario, the dollar keeps falling and gold keeps rising as it has since second 2001. It’s a consequence of a contest between the US commercial banks that set US economic policy and have called the shots in determining the global IMS on one side of the deal and China’s mercantilist, centrally planned, FIRE Economy on the other. In that scenario, China and its allies neutralize the US dominance of the IMS and force the US to stop living off its exorbitant privilege and then gradually reduce USD liabilities over time. We'll look at the first scenario later, but as the second is new to readers let’s start with the second scenario.

CI: I’m lost. Why can’t China, the US, and other countries just get together and hammer out a new IMS?

EJ: The Bretton Woods system was the first fully negotiated versus ad hoc or semi-ad hoc IMS. By the early 1960’s it was apparent that Triffin was right, that the IMS faced an eventual crisis because the US didn’t have enough gold to cover its constantly growing external liabilities due to the perpetual current account deficit that the US runs under the system. As the inevitable dollar crisis approached, a dozen meetings and conferences were held to look for ways to avert the crisis. None of them came to anything. The system finally collapsed in 1971 followed by nine years of global monetary chaos. Out of that chaos we got the IMS we have today, a lop-sided contraption that has gained legitimacy by legions of coin operated economists directly or indirectly on the payroll of the American and British commercial banks and financial institutions that benefit from the system.

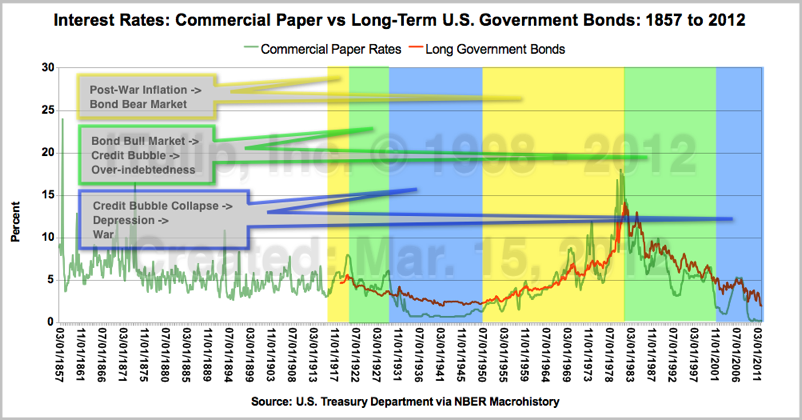

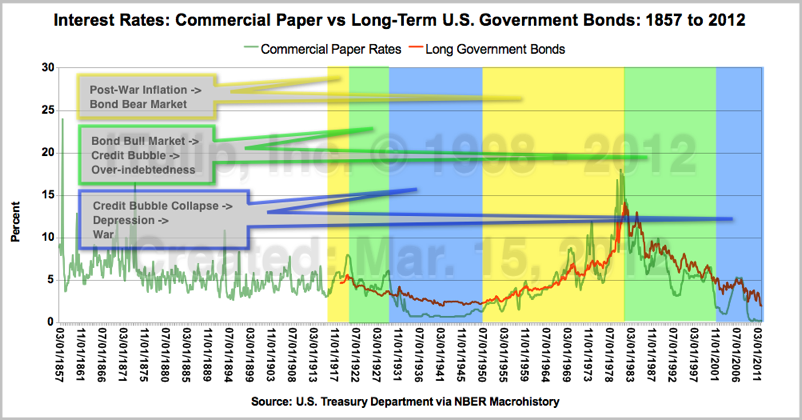

It appears to work because under the IMS central banks learned after the 1970s inflation crisis how to manage inflation without a gold standard. This turned out to be both a blessing and a curse. A blessing because financial markets operate far more efficiently with low inflation and low inflation volatility, that is, predictably low inflation because long-term loans are safe from principle losses due to the inflation tax. But sustained low interest rates are also a curse because they encourage over-indebtedness. One of the better books we read for this series is “A History of Interest Rates: Third Edition” by Sidney Homer. In this exhaustive tome that is the first and last word on interest rate history, they argue persuasively that the primary reason for periods of over-indebtedness that lead to debt crisis is government manipulation of interest rates downward.

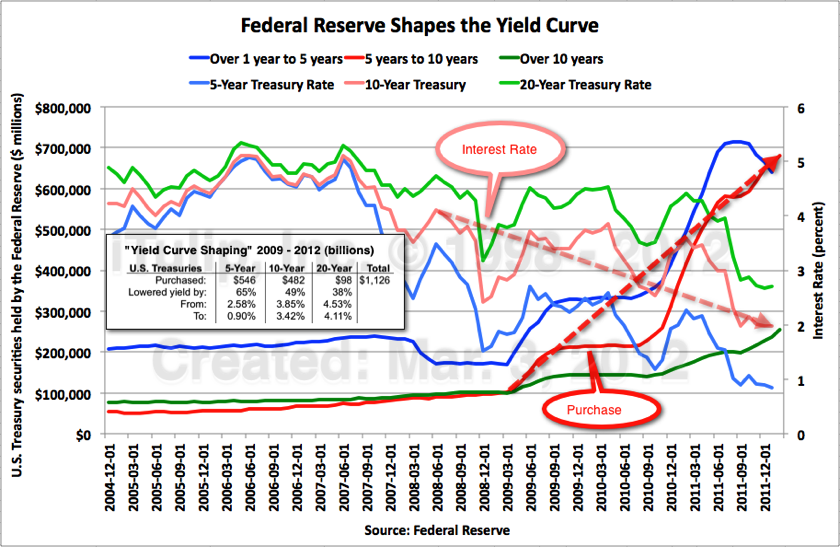

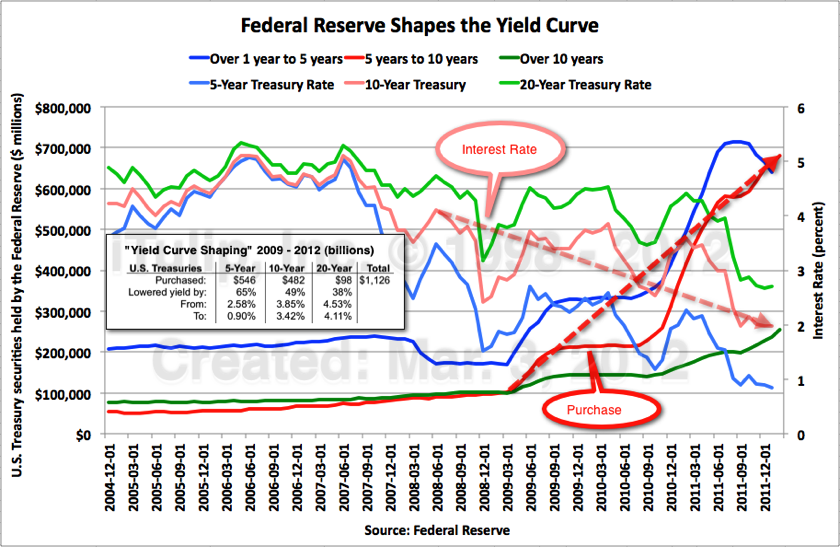

It happens in two stages. In the latest instance the nearly 30-year-long bull market in bonds that started in 1983 is the result of interest rates falling from 14% in 1983 to 5% at the time of the 2001 crash. That interest rate decline was due to markets responding to falling interest rates. The extension of the bull market since 2001 is the result of the Fed and Treasury fixing the price of Treasury bonds via extraordinary purchases, foreign and domestic. We charted the extraordinary purchases by China above, the foreign side of the reflation equation. Below we show the domestic side, the impact of the Fed trying to fix the price of long-term Treasury bonds, a policy central bankers prefer to refer to as "shaping the yield curve." The result is long rates pushed from 4% to 2% between the middle of 2008 and the end of 2011.

The Fed “shapes the yield curve, aka bond price fixing.

Bond bull markets, over-indebtedness, and global economic crisis.

The “lesson” that central bankers “learned” from the Great Depression was that deflation is the enemy of economic and political stability and monetary policies must to be aimed at preventing it, starting with the abolition of the deflationary gold standard. Then the “lesson” of 1970s was that without the discipline of the gold standard, inflation is the enemy of economic and political stability and monetary policies must to be aimed at preventing that. I think after 20 years of policies aimed at trying to control bond markets the lesson for central banks after the next crisis will be this: Stop Trying to Price Fix Bond Prices. Inflation is as necessary a part of the operation of markets as deflation to flush bad debt out of the economy.

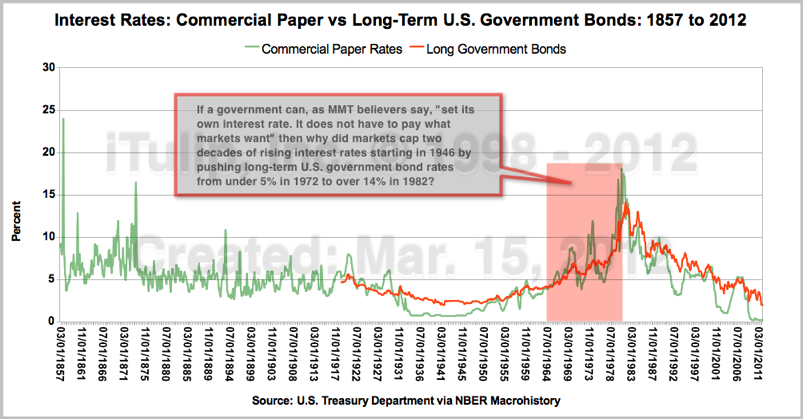

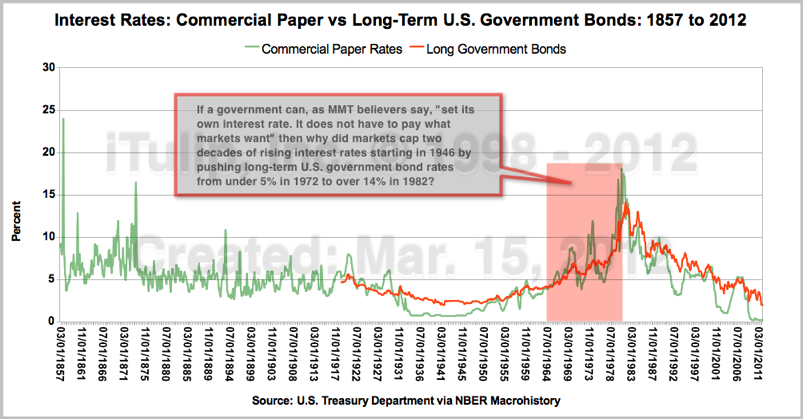

CI: Not to take you off track, and this has been an eye opener for me, but what about Modern Monetary Theory or MMT? It holds that a sovereign government doesn’t have to sell debt for a market price ever.

EJ: I’ve tried to engage the MMT crowd but they are too ideological for my purposes. Put a question in front of them backed by data that contests major MMT claims and they either run away or provide nonsensical responses. For example, this chart questions the blanket assertion that a sovereign government can always set the interest rate on its bonds.

Markets force the US government to rely on the kindness of foreign central banks to buy UST in 1978. They did this

buy choice? Really?

The response I got is that the US government set the rates high intentionally. Well, no, at one point during the Great Inflation crisis foreign central banks of countries aligned with the US were the only buyers of US Treasury bonds. The US started to issue Treasury bonds in foreign currencies. Not until 1979 did the Fed set rates above the rate of inflation and get things back under control. I have no use for theories that do not conform to the facts and the data. (continued $ubscription 5500 more words, 10 charts)

iTulip Select: The Investment Thesis for the Next Cycle™

__________________________________________________

To receive the iTulip Newsletter or iTulip Alerts, Join our FREE Email Mailing List

Copyright © iTulip, Inc. 1998 - 2012 All Rights Reserved

All information provided "as is" for informational purposes only, not intended for trading purposes or advice. Nothing appearing on this website should be considered a recommendation to buy or to sell any security or related financial instrument. iTulip, Inc. is not liable for any informational errors, incompleteness, or delays, or for any actions taken in reliance on information contained herein. Full Disclaimer

What would Robert Triffin (1910 - 1993) say about Ka-Poom Theory? This two part section of our multi-part Ka-Poom Theory Update Two series delve into the works of Belgian economist Robert Triffin. We summarize his in-depth critique of the international monetary system (IMS), his vision for a workable alternative in the 1960s and 1970s, and exhaustively quote and comment on his long-lost and forgotten final book, "IMS: International Monetary System or Scandal?" That book includes petulant protests penned in the final years of his life in the early 1990s as he observed the danger of an epic monetary crisis growing yet ignored by the international central banking community. He became disillusioned with “powerful politicians” and “special interests” that in his opinion thwarted IMS reform efforts for decades, reforms urgently needed to avert catastrophe. A fresh global monetary crisis has been building for 20 years since his last warning in 1992 a year before his death. Imbalances in the IMS have reached a breaking point over the years following the American Financial Crisis, and Triffin's analysis or the problem and his admonitions are more relevant than ever.

CI: Before we get to Triffin, how does the euro crisis relate to your Ka-Poom Theory? Is austerity for Greece and Spain the right solution? What would Triffin say?

EJ: You could say Triffin predicted Europe’s current crisis. In a rush to isolate and protect Europe from a usurious and dangerous US-centric IMS, Europe failed to get the structure right.

We got our hands on the last book Triffin published in 1992, a year before his death, provocatively titled "IMS: International Monetary System or Scandal?" It was published only in Europe by a relatively obscure organization, The European Policy Unit at the European University Institute. In it Triffin complains that IMS reforms were agreed to by the majority of major powers in 1974 but these were repeatedly vetoed by the US and UK. As a consequence of decades of delay, he warned that accumulated USD liabilities threatened the world economy with a currency crisis of epic proportions. That was 20 years ago when liabilities look quaint compared to 2012 levels.

US Dollars held as currency reserves at the time of Triffin’s 1992 warning increased 300% relative to global GDP by 2011.

CI: Briefly, who is Robert Triffin?

EJ: Belgian economist Robert Triffin predicted in 1959 that the Bretton Woods monetary system of currencies fixed to the dollar and redeemable in gold was doomed, which forecast proved accurate in 1971 when the Nixon administration ended gold redeem-ability. Below is a video of French President Charles de Gaulle echoing Triffin's concerns in 1965 and calling for reform.

After 1971 the IMS became based on a U.S. Treasury bond standard, that is, the debt-based fiat currency of the United States. Currencies then “floated” relative to each other. In practice that meant that rather than governments buying and selling currency to influence the quantity and thus the price of a currency to maintain exchange rates in a narrow band of less than 1%, governments allowed exchange rates to rise and fall with market demand, intervening only in times of crisis.

CI: Did Triffin anticipate the euro?

EJ: Triffin had a very clear vision of how a European currency needed to operate and was a proponent of a European central bank. He believed that first and foremost the point of a European currency was to insulate Europe from the disadvantages and unseemly risks posed by the US dollar based IMS that Charles de Gaulle refereed to as the "exorbitant privilege." In his words, “It [the euro] would, first of all, enable the monetary authorities of a United Europe to sterilize in the form of “consols” the vast overhang of short-term dollar indebtedness inherited from former US balance~of-payments deficits and threatening at any time a collapse of the dollar on the world exchange markets.”

CI: That was in 1992? Did Europe get the euro Triffin wanted?

EJ: No, it got half a currency. Europe wasn’t politically ready for a whole currency. To have a whole currency a complete set of institutions and mechanisms is needed to ensure, in Triffin’s words, “the harmonization of budgetary and monetary policies indispensable to the irrevocable stabilization of exchange rates.” In other words not only an institution to act as lender of last resort and maintain inflation but a federal European tax and budgetary authority to prevent “excessive or persistent financing of the countries in deficit by the countries in surplus.” He warned that if the euro was not so structured, “Germany runs the risk of becoming the ‘milch cow’ (vache à lait) of inflationary Community members.” And so it was.

CI: Triffin famously predicted the collapse of the international gold standard. Now we can say he predicted the euro’s present troubles?

EJ: The 1992 book is a goldmine of insights into the flaws in the IMS and their implications. That said, Triffin’s reform ideas had flaws of their own. He was kind of the George Soros of his day, with well-intentioned ideas about helping poor countries but with heavy government action (read: spending) to achieve it. We’ll focus on him in Part II and quote his book extensively.

To answer your question on austerity for Greece and Spain, the euro was badly structured; in the wake of recession caused by the American Financial Crisis, Germany has become the milch cow of Greece and Spain, at least in the eyes of German voters, as was feared in the earliest days of euro planning. Germany’s leaders have to contend with a chorus of “I told you so” from early euro skeptics among Germany’s elite, and the majority opinion of a voting public that Greece needs to go through painful economic restructuring as Germany did after unification with East Germany in the early 1990s. Austerity for Greece is politically sensible but economically insane.

CI: How do you mean?

EJ: Austerity for Greece now means a reduction in government expenditure during the recession that was caused by the American Financial Crisis in 2008. Such a policy is the exact opposite of the one followed at the time by the country with the world’s largest external debt and the worst budget deficit as a percent of GDP when it was in recession in 2008, the United States. Imagine the largest lender to the US, China, demanding that the US tighten its belt and get it fiscal house in order in 2008 and 2009. Instead, China tripled its loans to the US from $400 billion to $1.2 trillion. China used the crisis to gain leverage. Within the political confines of the EU, Germany cannot be so strategic.

CI: What’s happened to Greece, then?

EJ: The predictable result of austerity during a recession, as you can see below, is even higher unemployment and even more rapidly shrinking output.

Unemployment and GDP rates in Greece after the recession caused by the American Financial Crisis

was followed up with austerity measures that worsened both.

Obviously an economy that is shrinking is not growing its way out of debt.

The whole point of austerity is ostensibly to increase savings. An economy that is not able to invest in its future capacity to grow – spend on plant and equipment versus consumption – will never, ever be able to grow its way out of debt. Austerity has sent Greece into a death spiral.

Investment in the future of the Greek economy has plummeted 43% from €53 billion in 2007

to €30 billion in 2011 annually.

CI: Why is austerity being imposed on Greece if the policy is making matters worse for creditors?

EJ: The perverse logic of the euro’s institutional framework created this ludicrous “solution” for Greece that makes political sense but no economic sense. The policy is the inevitable outcome of a mis-match of monetary institutions and political institutions of the currency union. A similar mismatch is bringing down the IMS as a whole, in my opinion.

CI: Playing devil’s advocate here. Why can’t Greece change its economy the way the US did in the 1980s after the tough austerity programs of 1979 to 1983? The US boomed for decades after those recessions.

EJ: In 1983 the US had little private sector debt compared to today. Debt had been inflated away over the previous decade. Also, the US had little public debt and no external debt to speak of. If the Fed tried doing today as the Fed did in the early 1980s and the US economy would first collapse into a deflationary recession then, if the crisis went unresolved by a fresh round of external demand for US debt, a hyperinflationary depression. The US economy lives on the edge of that precipice and has since 2008.

CI: So austerity has no chance of working in Greece?

EJ: By analogy, say you take out a mortgage from the bank to buy a house and the payments consume 50% of your income instead of 20% or 30% as is usual because the bank was greedy and more interested in maximizing the asset, your debt, than in guaranteeing a flow of payments should boom times not last forever. Then you borrow more to buy a car. Those payments consume another 10% of your income. You have three jobs to cover the debt payments and all of your other expenses. You can barely keep up. You economize. You don’t eat out. You wife cuts your hair. You cancel your cable service. Then recession hits. You lose one of your three jobs. Your income falls. You warn the bank that you may miss a payment. “No, no, no. We can’t have that,” says the loan officer. “We lent you more money that we should have but that’s your problem not ours. We analyzed your finances and here is our demand: You must sell your car so that you can afford to keep making mortgage payments to us.” And you say, “But if I sell my car I can’t get to one of the two jobs I have left. My income will fall even more! I’ll be less not better able to pay my mortgage.” To which the loan officer replies, “That’s not our problem. My boss says that’s the only way.” You reply, “Well how about forgiving the part of the mortgage that you should not have lent me in the first place?” To which the bank replies, “We are contractually entitled to the loan in full.”

CI: So what happens?

EJ: If you sell your car and lose one of your jobs. You are, as a result, forced to default on the mortgage. You invoke your homestead exemption, the US property owner’s equivalent of national sovereignty. Your credit rating goes to hell and the bank loses everything. But soon another bank is at your door trying to lend you money.

CI: Do you think that eventually Greece be forced to bolt the euro like an over-indebted homeowner defaulting on a mortgage and invoking the homestead exemption, i.e., default on euro debts and operate with full sovereignty?

EJ: I don't see it at this point. A safer bet is that it works out in whatever way is best for the strongest members of the system, Germany and France. The history of all currency and monetary systems is the history of strong countries imposing their will on the weak. The strong are the creditors. The weak are the debtors. It has always been so. If Germany was stupid enough to put itself in harm’s way by allowing Greece to take on debts it can’t repay, then it is both the weak and the strong who will suffer the consequences. Greece is a small country with no capacity to work its way out of debt in the short term. Among the world’s economies it ranks 37th in GDP and 33rd in GDP-per-capita. Its main industry is tourism. Watch for Greek politics to become more radicalized. Look for candidates to begin to run on platforms split along pro- and anti-European Union lines. If you start to hear the phrase "Greek sovereignty" used in campaign speeches, then it is time to start thinking about Greek exiting the euro.

CI: Are you saying Germany needs to write off more of the Greece’s debt? Isn’t the crisis also the fault of corrupt Greek government for failing to collect taxes from the Greek elite?

EJ: Fair point about Greece’s regressive tax policies, but it’s not like Germany has the moral high ground. German lenders knew perfectly well that Greece’s finances were awful and the Greek government was lying about its fiscal position. The Drachma fell 26% versus the dollar in the two years immediately before Greece joined the euro in Jan. 2000, a clear warning that Greece was unable to manage its finances in a way that markets found convincing. But in those days the US tech bubble economy was booming and the fever spread worldwide. No one in power was thinking about a future euro crisis. The euro as structured is fundamentally a glorified currency board. Germany went along with Greece joining the euro because Germany wanted Greece to buy German BMWs and German weapons. That was the quid pro quo. But that part of the calculation of blame is lsot on the German people; looking like the leader who allows Germany to be treated like a milch cow by Greece and Spain is politically untenable.

If Greece defaulted and left the euro in 2013, the Drachma/US Dollar exchange rate might look like this.

CI: What if Greece did revert to the Drachma?

EJ: Best case the Drachma continued to decline at the same rate "under the peg" so to speak, since 2000 as from 1998 to 2000, around 30% againts the USD. In an actual default where Greek euro denominated debt is repudiated, I estimate the Drachma quickly loses another 50% over a six to 12 month period. It would be devastating for Greece and for the entire euro system, which is why I think it will be averted and German cow will keep supplying milk.

CI: Why so bad for the rest of the euro zone?

EJ: Because the euro, without the institutions that the US has behind the dollar, has had to count on the commercial banks to bail out Green, Spain, and others to hold up the euro -- and China, too. That means the banks are largely capitalized with euro bonds. If the euro bonds issued by Greece go to zero, those of Italy and others fall, too. The banks become insolvent and you have a European financial crisis to rival the US version, but instead of worthless mortgage-backed securities you have worthless or nearly worthless sovereign debt.

CI: Does China’s leadership look weak with respect to its loans to the US the say you are saying the German leadership will if it didn't push Greece for austerity? The US has worse total balance sheet liabilities than Greece does. Why doesn't China press the US to clean up its fiscal house?

EJ: The US is not a tiny Mediterranean country with little to offer and on the verge of default. The US, unlike Greece, can always pay its debts by expanding its federal balance sheet. US creditors may not like the resulting loss in purchasing power of the principle and interest payments they receive but they full well know the alternative in the context of the operation of the IMS -- collapse. It is no accident that China stepped up to bail out the US from its self-inflicted disaster in 2008 and 2009. China ensured a continuation of an IMS that, while unfair, has allowed them to grow and stay in power, while also buying more chips to play to control US foreign policy that impacts China.

China increased its holdings of US Treasury bonds 300% from $400 billion before the American Financial Crisis

To $1,200 after. Japan increased holdings 30% from $600 billion to $900 billion.

Russia increased holdings 1,309% from $34 billion to $138 billion.

The composition of major foreign holders of US Treasury Bonds (UST) changed in 2008 with the American Financial Crisis. Countries that are not under the de factor American military protectorate, notably China and Russia, picked up a large part of the tab. I don’t think they will ever demand cold turkey austerity for the US. Unlike German leaders who have an election cycle to deal with, China’s leaders are strategic. China can apply pressure on the US to reduce spending where they want us to. For example they can get us to back off on confrontations over China’s “unfair” currency policies, to stay out of their way in Africa and Latin America, their inroads into the Middle East, and so on. My contacts in China suggest that this has been going on through political back channels for years. This is why you see, for example, major reductions in US military spending today, apparently out of nowhere when reductions in other areas will be more effective from the standpoint of reducing liabilities and improving the US fiscal position.

CI: You think China is cheating on the rimnimbi/dollar exchange rate?

EJ: The IMS has since 1971 been in principle a floating exchange rate system. Markets not governments determine exchange rates, although under the system governments can intervene to stabilize rates at the extremes. Every major country in the world abides this arrangement except for China. China maintains a peg to the dollar under 1% as was the arrangement for all countries under the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates. We in the US are in no position to complain. We owe China too much money.

CI: You paint a picture of a US that is already subservient to China.

EJ: If asked how much foreign debt is too much, the simple answer is this. Too much foreign debt is the amount that causes a nation to stop making political decisions in its own interest. The US passed that point with China long ago. We are no longer a sovereign nation in relation to to China. We are afraid to call China out on its mobster ruling class of the Chinese police state, a fact that becomes painfully obvious when on occasion a foreign national gets offed or a dissident's family is rounded and jailed. Going into debt to China will turn out to be the worst economic policy error in America’s history, right up there with the Argentine’s going into debt to the British in the 1850s -- it was all downhill from there. I can't think of a worse country to be in debt to.

CI: Is this a change to your Economic MAD theory from April 2006 when you said China and the US are bound by a balance of economic terror? You said, “China and the U.S. are running inter-dependent bubble economies, relying on the economic equivalent of Mutually Assured Destruction (M.A.D.) to keep one from blowing up the other’s economy. Whether by intent or accident, sooner or later market forces will assert themselves and both economies will go through tough transitions.” Still true?

EJ: My formulation made it to the highest levels of policy making in China, I’m told, and it’s still the most rational way to look at the underlying dynamics of the relationship. Over the years you have seen the idea picked up and discussed such as it is in the article: US-China: The Threat of Economic MAD. But much has happened since I came up with that way of looking at the relationship, notably the American Financial Crisis and the first Peak Cheap Oil crisis in 2008. China has gained the upper hand and they are starting to play it.

Ka-Poom Theory Update Two – Part II: The pigs get fat and the hogs get slaughtered ($ubscription)

CI: Does a Ka-Poom dollar and debt crisis have to happen?

EJ: We’re talking about a total foreign liability of $10.2 trillion in highly liquid USD currency reserves held by foreign central and commercial banks, mostly in U.S. Treasury bonds, plus $5 trillion in federal debt held by foreign individuals, institutions and governments, also as interest bearing U.S. Treasury bonds. I'll answer your question with three more: International USD reserves alone totaled 14% of global GDP as of Q4 2011. How is it possible that these liabilities have grown so large since de Gaulle’s and Triffin’s warnings? Did Triffin misunderstand how the IMS was going to develop? What will happen?

There are two scenarios, as I see it. Keep in mind that the liabilities themselves are a result of the US blocking reform for decades but that today it is the scale of the liabilities themselves that forms the primary obstacle to reform. To negotiate such a vast quantity of U.S. federal government liabilities away, the terms of the IMS that generated it over the past 40 years will have to be re-negotiated by three major monetary interest groups with widely differing interests and objectives and an unequal level of the power to get their way, one led by the US and the other two led by China -- although “led” is too strong a word. “Influenced” is a better word.

In the first Ka-Poom crisis scenario, this negotiation takes place under the duress, without an institutional framework designed to operate in such a crisis, and with the US doing everything in its power to maintain the status quo as we have for the past 40 years. Ka-Poom is a disorderly end to the IMS as in 1971 but without the US as a dominant power able to shove everyone else on the planet into line over the course of a decade until the system is working. In that scenario, if you thought the monetary chaos that produced the Great Inflation of the 1970s was bad, in the Ka-Poom scenario it’s ever nation for itself, and you’d better have a decent-sized gold reserve to stay in the global trade game. In that scenario, Treasury bond yields rise into double digits and the dollar exchange rate falls to $5000 per ounce of gold or worse.

CI: Worse? $5000 gold sounds good to me!

EJ: But it isn't. If you own gold you really want the second scenario, the less dramatic "bleed them out" scenario as China and her allies work the system to marginalize the US over decades. You may still get to $5000 gold but without the unseemly political chaos and financial hardship that billions of people would endure, including friends and family.

In the “bleed them out” scenario, the dollar keeps falling and gold keeps rising as it has since second 2001. It’s a consequence of a contest between the US commercial banks that set US economic policy and have called the shots in determining the global IMS on one side of the deal and China’s mercantilist, centrally planned, FIRE Economy on the other. In that scenario, China and its allies neutralize the US dominance of the IMS and force the US to stop living off its exorbitant privilege and then gradually reduce USD liabilities over time. We'll look at the first scenario later, but as the second is new to readers let’s start with the second scenario.

CI: I’m lost. Why can’t China, the US, and other countries just get together and hammer out a new IMS?

EJ: The Bretton Woods system was the first fully negotiated versus ad hoc or semi-ad hoc IMS. By the early 1960’s it was apparent that Triffin was right, that the IMS faced an eventual crisis because the US didn’t have enough gold to cover its constantly growing external liabilities due to the perpetual current account deficit that the US runs under the system. As the inevitable dollar crisis approached, a dozen meetings and conferences were held to look for ways to avert the crisis. None of them came to anything. The system finally collapsed in 1971 followed by nine years of global monetary chaos. Out of that chaos we got the IMS we have today, a lop-sided contraption that has gained legitimacy by legions of coin operated economists directly or indirectly on the payroll of the American and British commercial banks and financial institutions that benefit from the system.

It appears to work because under the IMS central banks learned after the 1970s inflation crisis how to manage inflation without a gold standard. This turned out to be both a blessing and a curse. A blessing because financial markets operate far more efficiently with low inflation and low inflation volatility, that is, predictably low inflation because long-term loans are safe from principle losses due to the inflation tax. But sustained low interest rates are also a curse because they encourage over-indebtedness. One of the better books we read for this series is “A History of Interest Rates: Third Edition” by Sidney Homer. In this exhaustive tome that is the first and last word on interest rate history, they argue persuasively that the primary reason for periods of over-indebtedness that lead to debt crisis is government manipulation of interest rates downward.

It happens in two stages. In the latest instance the nearly 30-year-long bull market in bonds that started in 1983 is the result of interest rates falling from 14% in 1983 to 5% at the time of the 2001 crash. That interest rate decline was due to markets responding to falling interest rates. The extension of the bull market since 2001 is the result of the Fed and Treasury fixing the price of Treasury bonds via extraordinary purchases, foreign and domestic. We charted the extraordinary purchases by China above, the foreign side of the reflation equation. Below we show the domestic side, the impact of the Fed trying to fix the price of long-term Treasury bonds, a policy central bankers prefer to refer to as "shaping the yield curve." The result is long rates pushed from 4% to 2% between the middle of 2008 and the end of 2011.

The Fed “shapes the yield curve, aka bond price fixing.

Bond bull markets, over-indebtedness, and global economic crisis.

The “lesson” that central bankers “learned” from the Great Depression was that deflation is the enemy of economic and political stability and monetary policies must to be aimed at preventing it, starting with the abolition of the deflationary gold standard. Then the “lesson” of 1970s was that without the discipline of the gold standard, inflation is the enemy of economic and political stability and monetary policies must to be aimed at preventing that. I think after 20 years of policies aimed at trying to control bond markets the lesson for central banks after the next crisis will be this: Stop Trying to Price Fix Bond Prices. Inflation is as necessary a part of the operation of markets as deflation to flush bad debt out of the economy.

CI: Not to take you off track, and this has been an eye opener for me, but what about Modern Monetary Theory or MMT? It holds that a sovereign government doesn’t have to sell debt for a market price ever.

EJ: I’ve tried to engage the MMT crowd but they are too ideological for my purposes. Put a question in front of them backed by data that contests major MMT claims and they either run away or provide nonsensical responses. For example, this chart questions the blanket assertion that a sovereign government can always set the interest rate on its bonds.

Markets force the US government to rely on the kindness of foreign central banks to buy UST in 1978. They did this

buy choice? Really?

The response I got is that the US government set the rates high intentionally. Well, no, at one point during the Great Inflation crisis foreign central banks of countries aligned with the US were the only buyers of US Treasury bonds. The US started to issue Treasury bonds in foreign currencies. Not until 1979 did the Fed set rates above the rate of inflation and get things back under control. I have no use for theories that do not conform to the facts and the data. (continued $ubscription 5500 more words, 10 charts)

iTulip Select: The Investment Thesis for the Next Cycle™

__________________________________________________

To receive the iTulip Newsletter or iTulip Alerts, Join our FREE Email Mailing List

Copyright © iTulip, Inc. 1998 - 2012 All Rights Reserved

All information provided "as is" for informational purposes only, not intended for trading purposes or advice. Nothing appearing on this website should be considered a recommendation to buy or to sell any security or related financial instrument. iTulip, Inc. is not liable for any informational errors, incompleteness, or delays, or for any actions taken in reliance on information contained herein. Full Disclaimer

Comment