Essential Trends - Part I-A: Gold in an Era of Global Monetary System Regime Change

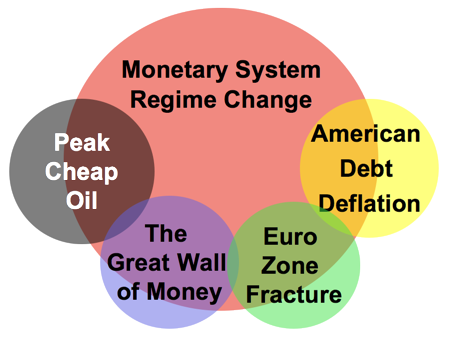

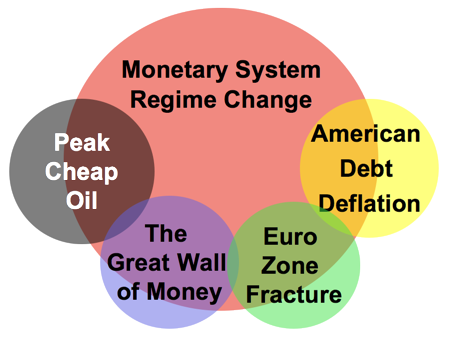

This six part series explores the five of the major macro-economic trends of our time. Each part covers one major trend, then we pull them all together in Part VI.

Monetary Regime Change, American Debt Deflation, and Peak Cheap Oil are updates to previous analysis and are already familiar concepts to long time readers, although they will be explained in this new series simply to help new readers to quickly grasp the concepts.

The Great Wall of Money expands previous analysis of China's unsustainable economy into a more fully formed theory of the Chinese economy. A key element is the idea that the distinction between the balance sheets of China's commercial banks and its central bank are so blurred that they may be considered from a monetary policy viewpoint as a single, gigantic balance sheet. The implication is that while the crash we forecast back in October 2010 to occur in Q4 2011 is proceeding as expected, it is unlikely to be the end of the road for the Chinese system.

Euro Zone Fracture is a new concept for us. It develops the theory that weaker countries that have always been a poor fit within the euro zone structure will be thrown off, like children from a Merry-go-Round when it spins too fast to allow the weaker players to keep their grip, but the system will hold together overall with the euro re-enforced to be more of a true currency rather than a super currency peg.

The approach taken in the analysis is to frame each trend between two forces that are the key processes drivers. In the case of Euro Zone Fracture the force of increased federalization on one side opposes the force of increased tribalism on the other, with credit committee negotiation complexity and time constraints the greatest impediment to resolution. In the case of American Debt Deflation the political strength of special interests to maintain the flow of payments to repay bubble era debt opposes the political tension created by high unemployment and weak economic growth that deflation causes. By framing each trend process between two opposing forces, all five can be combined in ways that allow us to explore their interaction and propose likely outcome scenarios and impacts on asset classes on a time line. We attempt to keep this all simple enough that readers don't get lost in the language and minutia.

The processes underlying each trend are in some crucial way limited. Each will force dramatic change through crisis, some sooner than later. This is what makes these particular five trends so important. For example, the Peak Cheap Oil trend process is limited by the finite supply of oil that can be produced at a cost that does not tax the global economy into negative growth. The American Debt Deflation trend process is limited by the electoral system, despite the appearance that it leaves voters with no choices.

The diagram above depicts the five major trend change processes. The diagram also corresponds to the organization of the New iTulip that we now hope to launch later this month. We expect each part of this series to come out roughly every two weeks. In addition there will be more frequent short updates, getting back to the original concept of my original Quick Comment and Urgent Message going back to 1998, when I was blogging before there were blogs. It is there where I will comment on my experiences on a panel at a black tie fund raiser at the Nixon Library tomorrow in Yorba Linda, California with Doug Duncan, chief economist for Fannie Mae; Debra Still, chairman elect of the Mortgage Bankers Association; and my old friend Sean O’Toole, president of Foreclosure Radar. The following week I attend an invitation-only conference at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston "The Long-Term Effects of The Great Recession" where Bernanke gives the keynote and will post comments on that as well.

Monetary Regime Change is depicted in the diagram above as a meta-trend at the center as it both influences all others and is influenced by them. It is here that we logically begin the series.

Gold in an Era of Global Monetary System Regime Change

Photo Credit: Alyce Taylor, 2008

I’m in a conference room in Cambridge, Massachusetts this summer with a friend who runs a venture capital firm. We get to talking about gold.

He tells me, “I might invest in gold if anyone can tell me what it is.”

It wasn’t the time or place for me to launch into my idea of the meaning of gold in our time, that gold is a stand-by alternative currency for international contract settlement if and when the U.S. Treasury dollar system finishes breaking down.

I’m immediately confronted with the uncomfortable truth that I cannot name a single article for my friend to read that simply and plainly explains why, among investments in technology company stocks, commodity ETFs, TIPS, municipal bonds, REITs, and myriad financial instruments that track the economy and hedge risk, the element AU, atomic number 79 on the periodic table -- metal -- belongs in the investment portfolio of a sane and reasonable person in the year 2011.

Isn’t gold ever so 1879?

Since 2001 when I decided to enter the gold market as an investor I have published dozens of articles about gold, but none of these were intended as a gold investing primer. They are engagements in the battle for the hearts and minds of the world’s investors who remain disproportionately enamored of the cleverly and ubiquitously marketed magical properties of equities. My motives for engaging this fight will become clear as you read on.

The struggle was dominated then, ten years ago, by doctrinaire gold fanatics. Back then they were talking to themselves. Gold was dismissed and forgotten as irrelevant by mainstream investors, and the media that catered to them was busy helping Wall Street convey the speculative fervor of a credulous investing public from the wreckage of the collapsed stock market bubble to a nascent housing bubble. The unfeigned were whipped up into a frenzy of get-rich-quick housing speculation fervor from 2002 to 2006. The object was to drive demand for billions of dollars of mortgage-backed securities sales, to generate fees for Wall Street firms.

Gold did not make the pages of the Wall Street Journal and the New York Times until five years after steady gold price increases made gold newsworthy again. But the articles did not investigate the causes of a curiously persistent and steady rise in gold prices after decades in the doldrums. Instead, readers were treated to the repetition of a short, concise, and easily absorbed gold-is-a-bad-investment script.

Until recently in order to get an article or editorial on gold published in a mainstream periodical it needed to include the following checklist of arguments against owning gold:

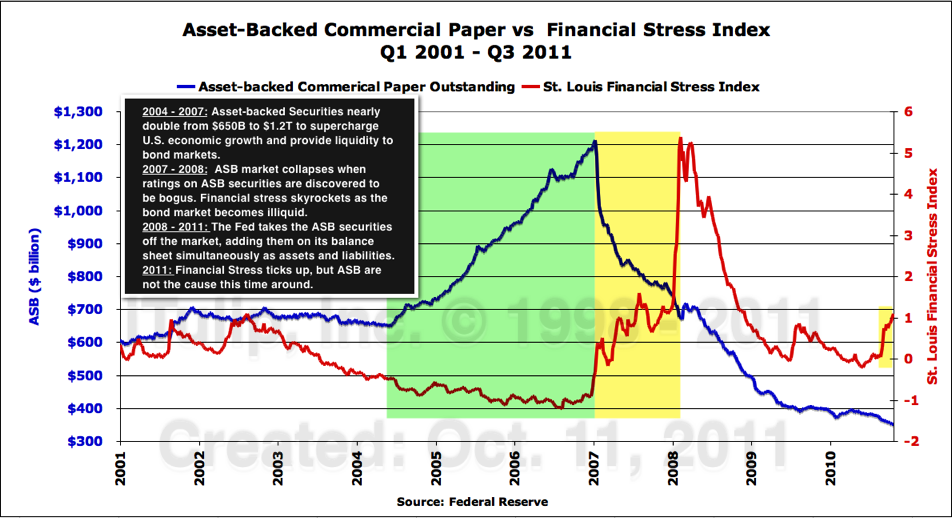

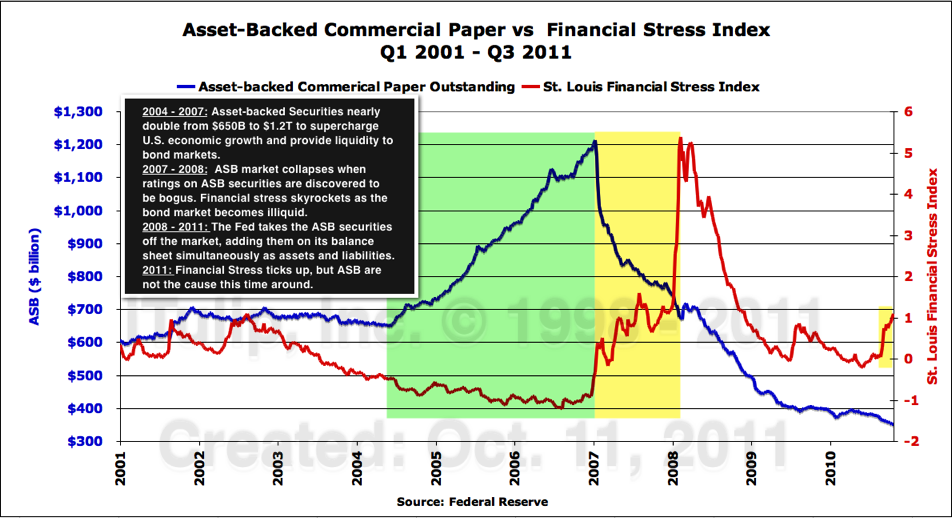

Then, in 2008, two years after the housing bubble peaked, the rigged market for securities that backed U.S. home mortgages and other debt collapsed, taking down the U.S. financial system, then the global financial system, and finally the global economy. The full repercussions of this series of events have yet to be felt.

These events were subsequently papered over with the obfuscatory label Global Financial Crisis, as if the crisis appeared furtively like a ship running aground in a dense fog rather than conspicuously like an orphanage exploding after the janitor flicked his lit cigarette downstairs into the hidden fireworks factory in the basement.

The crisis proceeded along an easily traced chain of causation originating from a readily identifiable source: a profoundly corrupt regulatory apparatus that America's paid-off Fourth Estate let run amok for years, selling debt securities that put the entire financial system at risk. The dangers of Credit Risk Pollution produced by these securities was evident in 2006, in plenty of time to prevent the financial system wreckage that occurred years later.

Here on iTulip we refuse to play along and use the term Global Financial Crisis. The American Financial Crisis, or AFC, originated in the U.S. then spread to the rest of the world -- and still dogs it. One cannot grasp the meaning behind gold's rise since 2001 without first acknowledging that the conditions of the American political economy which gave rise to the AFC are driving gold prices higher.

Drivers of Global Monetary Regime Change

In the wake of the AFC, gold prices surged but not for the reasons that Nouriel Roubini, George Soros, and others claimed on the pages of the WSJ and the NYT at the time. The surge was not a consequence of retail investors panicking out of stocks and bonds into gold. In fact, the gold price plunged in the heat of the liquidity panic early in the AFC as retail buyers and hedge funds sold gold to raise cash. The price rise that followed the AFC reflected a new stage in global monetary regime change which began in 2001.

In theory, the world’s major reserve currency used in international trade need not be backed by a commodity such as gold as it was from the 1840s until 1971 when U.S. Treasury bond became the world’s monetary reserve asset, and the U.S. dollar the unit of that reserve.

If a single nation among all nations meets the following criteria, it can issue the world’s reserve currency and be trusted to maintain the value of that currency if it meets at least these three criteria:

The bond market need not be perfectly liquid and transparent nor the central bank perfectly trustworthy and disciplined, only that these be significantly more in evidence for the country issuing a reserve currency than for the other members of the monetary system who are parties to it.

The technology bubble was, in my opinion, the firing gun that communicated to other participants of the global monetary system that systemic and possibly venal corruption had infected the world’s reserve currency issuer.

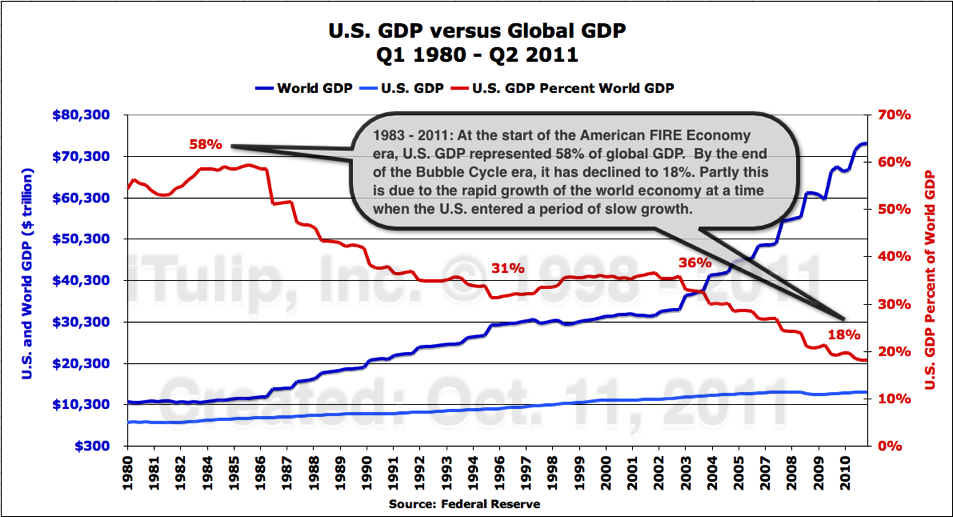

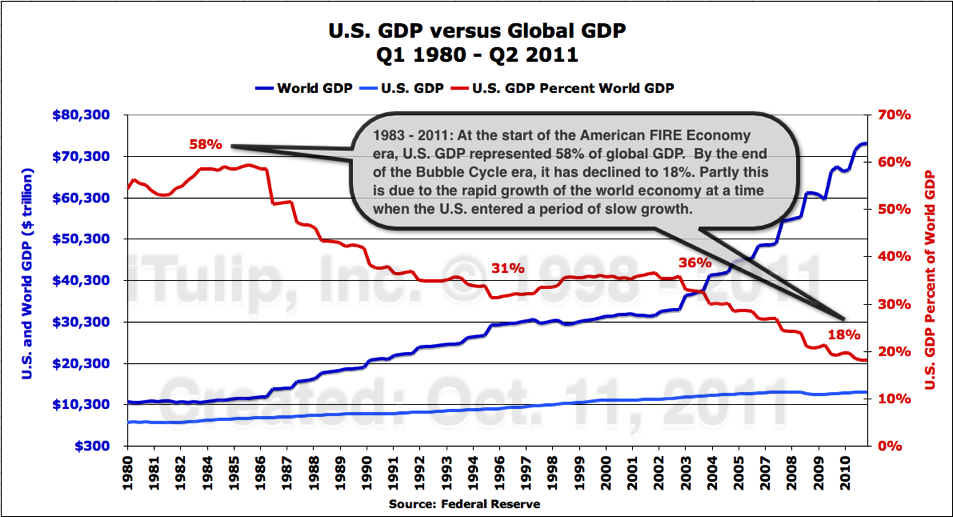

Foreign institutional and official market participants began to respond rationally to evidence that in addition to the fact that the U.S. no longer held a dominant share of global output, U.S. leaders and institutions were taking on the unseemly character traits and behavior of their own.

They began to think, “If I want to put my money into a corrupt and unreliable banking and financial system, I can keep it here at home. I don’t need to bother with the U.S.” Paradoxically, at the same time, in countries such as Brazil, technocrats trained at U.S. universities were applying the very U.S. principles of market transparency and efficiency that the U.S. was abandoning.

As the global monetary system based on U.S. Treasury bonds does not have an official Plan B should the system fail, the unofficial Plan B has always been gold. At least that was my theory back in 2001. In 2001, with the crash of the stock market bubble the U.S. began to lose its legitimacy as the world’s reserve currency issuer and gold prices began to rise.

Global investor epiphany

In 2009 the AFC accelerated the global investor awareness of this new, more unseemly character of the American political economy.

Gold as fallback reserve currency was to my mind in 2001 the only rational argument available to explain why central banks continued to hold more than 20% of all of the gold ever produced in history as reserve assets 30 years after gold was officially de-linked from the global monetary system.

Readers who have been following along with my theory of gold since 2001 were not surprised to find that starting in Q2 2009, in the wake of the AFC, global central banks became net buyers of gold for the first time since after WWII.

How much longer can the tail of the global economy wag the global money system dog?

The U.S. no longer dominates the world economy as it did when the global currency arrangement was created.

This brings us back to the matter of mainstream media coverage of gold. Starting in 2009, the anti-gold checklist disappeared from articles in the mainstream media about gold.

After the AFC, imploring investors to avoid gold for checklist reasons was no longer credible.

With interest rates pushed to near zero to reflate the economy after the crash, no one cares that gold does not earn interest.

The AFC made the public intensely aware that the stock market in inflation-adjusted terms has declined by double digits over the past decade while gold increased five-fold, steadily, year after year, demolishing the argument that gold always performs worse than stocks over the long term.

Stock market volatility between 2001 and 2009 was so extreme it made gold price movements look tedious.

It also became painfully clear that faith in the single family home as a foolproof investment had collapsed along with the housing bubble.

Today, newcomers to the gold market who look to the pages of the Wall Street Journal and the New York Times for insight into the meaning of gold are no longer accosted with a stream of anti-gold propaganda but are still treated to the occasional article warning that gold is a dangerous bubble, yet even instances of these dubious warnings grow rare as it dawns on the public mind that the bi-annually predicted impending gold bubble collapse has failed to materialize for more than five years.

That still leaves a tangle of confusing motives and viewpoints charged with emotion. Gold may not be magnetic, but it attracts passionate opinion as no other asset class can.

Politics of Gold

Pity the neophyte as he or she first enters the world of gold as a financial asset. The newcomer thinks of gold as a rare, soft, beautiful yellow metal used in jewelry to embellish souls or in electronic circuits to protect parts against corrosion. Enter the brawling gold investment forum and suddenly gold takes on a thousand colors.

To the true believers gold is at once a symbol of righteousness and honesty, a beacon of light to lead a lost people from the badlands of government-made money, a solid moral anchor for a errant relativist culture, and a personal financial life raft to float the family homestead in a tsunami tide of economic destruction when the inevitable Day of Reckoning arrives.

The true believers have a name. They are called gold bugs.

On the other side of the argument are equally ardent gold detractors, many of whom vilify gold as fervently as true believers glorify it. The vehemence of their arguments against investing in gold belies the self-doubt that arises from not knowing how to answer the question: “Why did I remain in the stock market and keep faith in a conspicuously manipulated financial system for so long? Why have gold prices gone up every year since 2001 while stocks fell? Why didn’t I buy gold when the price was lower?”

The silent self-flagellation that occupies millions of prospective gold investors is unjustified. To a far greater extent than they may be willing to accept, the misinformed condition of the American investors’ mind with respect to gold investment, which condition led to the decisions they made, is not entirely their fault.

Discussion of gold as an investment has become a crazed team sport divided between passionate fanatics and correspondingly vehement detractors, with an irritable audience of mainstream investors in the stands scratching their heads, wondering what all of the fuss is about.

In their defense, the mainstream business media struggles to find credible, independent sources of gold market knowledge. The views of the most knowledgeable are the most suspect for being the least dispassionate.

Who but a Dodger’s fan can cite each player’s record of assists, double plays, and errors, and who but a gold bug can cite the last time gold prices previously spiked and fell on a percentage basis as much as between August 1 to September 30, 2011 and why?

Perversely this credibility gap means that the less you know about gold, the more trusted you are as a dispassionate source. In fact, in order to qualify as a true gold expert you need to know nothing about it whatsoever.

That leaves the hapless retail buyer left to read the opinions of either the fanatical or the benighted. Each provides a belief-specific awareness filter on the facts.

For example, a gold bug will tell you that gold was illegal for Americans to own from 1933 until 1974, which is true, but then he will spin this into a tale of government goons cracking open safe deposit boxes to confiscate gold. The fact is that that the law was so weak that it was enforced only once in 40 years, and that single case was dismissed.

The truth of the episode of the gold's 41 years as contraband is more interesting than the conspiracy theories. The majority of gold investors, who become known as gold hoarders whenever the government needs it, turned in gold voluntarily before the May 1, 1933 legal deadline set by FDR’s order. They did so for largely patriotic reasons, to help rescue the economy that had been in a deflationary death spiral for three years under the non-leadership of Herbert Hoover.

Sixty-five years later, in the depths of the Asian Currency Crisis in 1998, without force of law millions of Koreans scraped together more than a billion dollars worth of gold jewelry, coins and other personal items to give to the government voluntarily to be melted down to shore up the central bank's reserves. To put this egalitarian behavior into context, thousands of Korean college students had to go home to their families in Seoul that year from the U.S. because the won had so depreciated that savings in domestic bank accounts could not cover tuition. City parks filled with the unemployed when only months before unemployment was largely unknown. It was a classic Sudden Stop event (see Headed for a Sudden Stop, 2008). The populace rallied in the nation’s time of need, turning in gold to shore up the system for the greater good.

This nuanced interpretation of gold's function in a currency crisis is critical to get right because it suggests how the latest episode in the life of gold as a monetary asset is most likely to end. Rather than by government confiscation as gold fanatics warn, I have argued since 2001 that the most probable endgame is for global monetary crisis to force the U.S. to re-open the gold window, a concept I explain in detail later, with gold turned in by U.S. citizens voluntarily to increase U.S. holdings from 8,133 tons today to enough to truly back the full faith and credit of the U.S. Treasury.

Gold as Protection Against the Causes and Effects of Global Monetary Regime Change

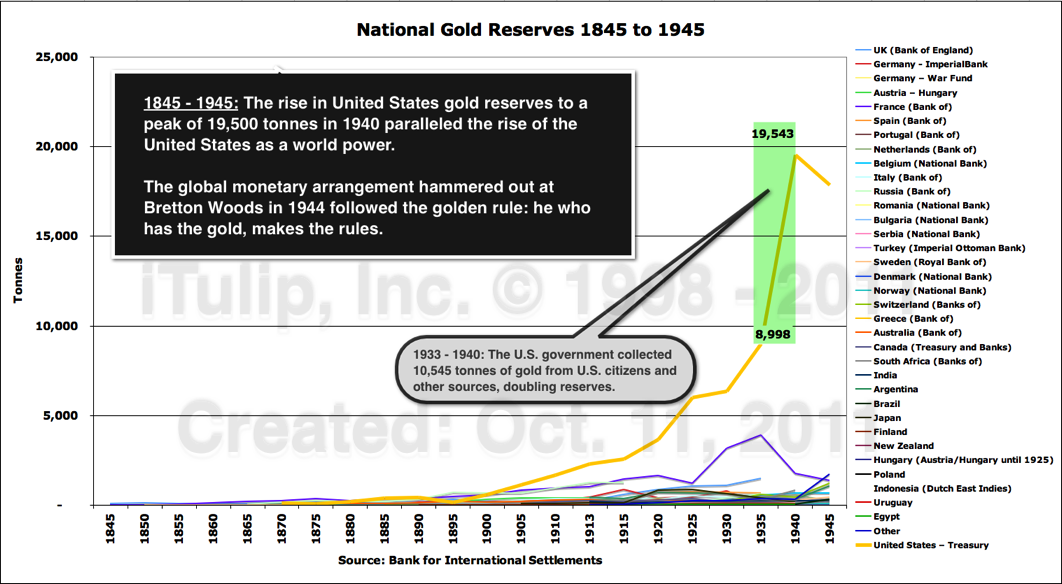

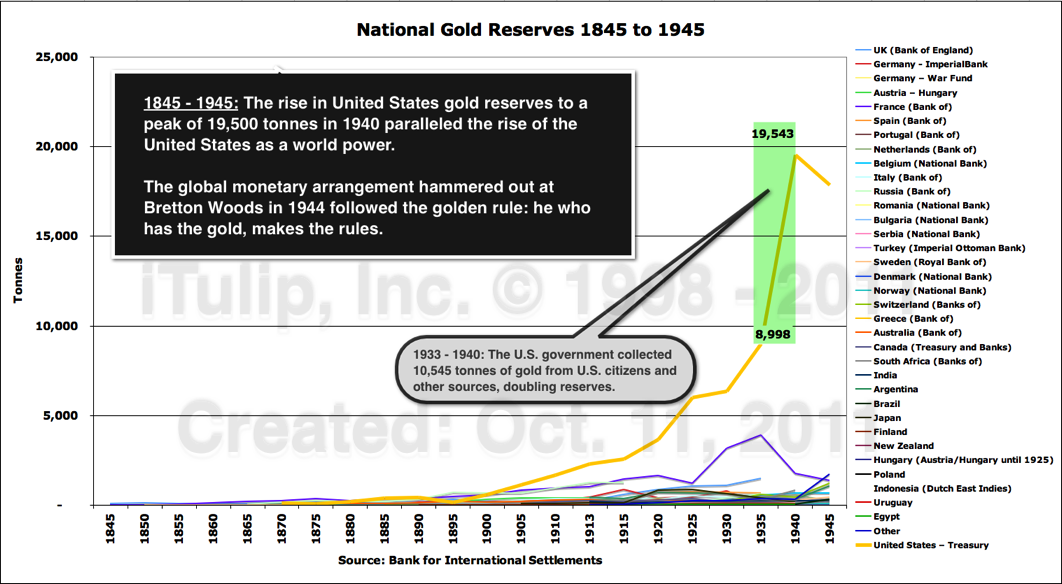

My investigation into gold starting in 1998 and culminating in 2001 with a major purchase focused on an anomaly of central banks and national treasuries: they publicly proclaimed gold irrelevant while they continued to hold in excess of 20% of all of the gold ever produced. Not only that, but the distribution of gold reserves struck me as geopolitically telling.

The United States with 8,134 tonnes has by far the largest gold reserves, followed by Germany at 3,401, the IMF at 2,814, Italy at 2,452, and France at 2,435. Altogether the world's governments own 30,407 tonnes. Thirty thousand tonnes struck me as rather a lot of anything for governments to own that they collectively profess has no value or purpose. The question, then, was what value and purpose does gold still have in government vaults? Answer that question, I told myself, and I can forecast where gold prices are going to go.

One way to approach the question is to investigate how gold got into the government vaults in the first place. It didn't appear out of thin air. The history was undoubtedly long and complex, but at the heart of it were principles that hold throughout the ages.

Essential Trends - Part I-B: Gold in an Era of Global Monetary System Regime Change

The history of our modern world is written in the gold reserves holdings chart above. I will not attempt to cover all of the ebbs and flows of gold reserves of 35 nations between 1845, through the global financial crisis of the 1860s, WWI, and WWII. The obvious point that this chart makes is that the U.S. has since the end of WWI held far more gold than any other country. Also, measures to collect gold from U.S. citizens were highly effective at expanding national reserves.

The second largest national gold reserves during this period were held in the vaults of The Bank of France. If you take the U.S. out of the picture, gold reserves over the same period looks like this, with France dominance beginning in the 1860s until the 1890s when the Bank of Russia kept up with French gold reserves until the Russian Revolution. (Continued... $ubscription)

iTulip Select: The Investment Thesis for the Next Cycle™

__________________________________________________

To receive the iTulip Newsletter or iTulip Alerts, Join our FREE Email Mailing List

Copyright © iTulip, Inc. 1998 - 2009 All Rights Reserved

All information provided "as is" for informational purposes only, not intended for trading purposes or advice. Nothing appearing on this website should be considered a recommendation to buy or to sell any security or related financial instrument. iTulip, Inc. is not liable for any informational errors, incompleteness, or delays, or for any actions taken in reliance on information contained herein. Full Disclaimer

This six part series explores the five of the major macro-economic trends of our time. Each part covers one major trend, then we pull them all together in Part VI.

Monetary Regime Change, American Debt Deflation, and Peak Cheap Oil are updates to previous analysis and are already familiar concepts to long time readers, although they will be explained in this new series simply to help new readers to quickly grasp the concepts.

The Great Wall of Money expands previous analysis of China's unsustainable economy into a more fully formed theory of the Chinese economy. A key element is the idea that the distinction between the balance sheets of China's commercial banks and its central bank are so blurred that they may be considered from a monetary policy viewpoint as a single, gigantic balance sheet. The implication is that while the crash we forecast back in October 2010 to occur in Q4 2011 is proceeding as expected, it is unlikely to be the end of the road for the Chinese system.

Euro Zone Fracture is a new concept for us. It develops the theory that weaker countries that have always been a poor fit within the euro zone structure will be thrown off, like children from a Merry-go-Round when it spins too fast to allow the weaker players to keep their grip, but the system will hold together overall with the euro re-enforced to be more of a true currency rather than a super currency peg.

The approach taken in the analysis is to frame each trend between two forces that are the key processes drivers. In the case of Euro Zone Fracture the force of increased federalization on one side opposes the force of increased tribalism on the other, with credit committee negotiation complexity and time constraints the greatest impediment to resolution. In the case of American Debt Deflation the political strength of special interests to maintain the flow of payments to repay bubble era debt opposes the political tension created by high unemployment and weak economic growth that deflation causes. By framing each trend process between two opposing forces, all five can be combined in ways that allow us to explore their interaction and propose likely outcome scenarios and impacts on asset classes on a time line. We attempt to keep this all simple enough that readers don't get lost in the language and minutia.

The processes underlying each trend are in some crucial way limited. Each will force dramatic change through crisis, some sooner than later. This is what makes these particular five trends so important. For example, the Peak Cheap Oil trend process is limited by the finite supply of oil that can be produced at a cost that does not tax the global economy into negative growth. The American Debt Deflation trend process is limited by the electoral system, despite the appearance that it leaves voters with no choices.

The diagram above depicts the five major trend change processes. The diagram also corresponds to the organization of the New iTulip that we now hope to launch later this month. We expect each part of this series to come out roughly every two weeks. In addition there will be more frequent short updates, getting back to the original concept of my original Quick Comment and Urgent Message going back to 1998, when I was blogging before there were blogs. It is there where I will comment on my experiences on a panel at a black tie fund raiser at the Nixon Library tomorrow in Yorba Linda, California with Doug Duncan, chief economist for Fannie Mae; Debra Still, chairman elect of the Mortgage Bankers Association; and my old friend Sean O’Toole, president of Foreclosure Radar. The following week I attend an invitation-only conference at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston "The Long-Term Effects of The Great Recession" where Bernanke gives the keynote and will post comments on that as well.

Monetary Regime Change is depicted in the diagram above as a meta-trend at the center as it both influences all others and is influenced by them. It is here that we logically begin the series.

Gold in an Era of Global Monetary System Regime Change

Photo Credit: Alyce Taylor, 2008

I’m in a conference room in Cambridge, Massachusetts this summer with a friend who runs a venture capital firm. We get to talking about gold.

He tells me, “I might invest in gold if anyone can tell me what it is.”

It wasn’t the time or place for me to launch into my idea of the meaning of gold in our time, that gold is a stand-by alternative currency for international contract settlement if and when the U.S. Treasury dollar system finishes breaking down.

I’m immediately confronted with the uncomfortable truth that I cannot name a single article for my friend to read that simply and plainly explains why, among investments in technology company stocks, commodity ETFs, TIPS, municipal bonds, REITs, and myriad financial instruments that track the economy and hedge risk, the element AU, atomic number 79 on the periodic table -- metal -- belongs in the investment portfolio of a sane and reasonable person in the year 2011.

Isn’t gold ever so 1879?

Since 2001 when I decided to enter the gold market as an investor I have published dozens of articles about gold, but none of these were intended as a gold investing primer. They are engagements in the battle for the hearts and minds of the world’s investors who remain disproportionately enamored of the cleverly and ubiquitously marketed magical properties of equities. My motives for engaging this fight will become clear as you read on.

The struggle was dominated then, ten years ago, by doctrinaire gold fanatics. Back then they were talking to themselves. Gold was dismissed and forgotten as irrelevant by mainstream investors, and the media that catered to them was busy helping Wall Street convey the speculative fervor of a credulous investing public from the wreckage of the collapsed stock market bubble to a nascent housing bubble. The unfeigned were whipped up into a frenzy of get-rich-quick housing speculation fervor from 2002 to 2006. The object was to drive demand for billions of dollars of mortgage-backed securities sales, to generate fees for Wall Street firms.

Gold did not make the pages of the Wall Street Journal and the New York Times until five years after steady gold price increases made gold newsworthy again. But the articles did not investigate the causes of a curiously persistent and steady rise in gold prices after decades in the doldrums. Instead, readers were treated to the repetition of a short, concise, and easily absorbed gold-is-a-bad-investment script.

Until recently in order to get an article or editorial on gold published in a mainstream periodical it needed to include the following checklist of arguments against owning gold:

- Gold does not earn interest as bonds do.

- Gold performs poorly as a long-term investment versus stocks and residential real estate.

- Gold prices are highly volatile.

- Gold is a dangerous bubble about to pop

Then, in 2008, two years after the housing bubble peaked, the rigged market for securities that backed U.S. home mortgages and other debt collapsed, taking down the U.S. financial system, then the global financial system, and finally the global economy. The full repercussions of this series of events have yet to be felt.

These events were subsequently papered over with the obfuscatory label Global Financial Crisis, as if the crisis appeared furtively like a ship running aground in a dense fog rather than conspicuously like an orphanage exploding after the janitor flicked his lit cigarette downstairs into the hidden fireworks factory in the basement.

The crisis proceeded along an easily traced chain of causation originating from a readily identifiable source: a profoundly corrupt regulatory apparatus that America's paid-off Fourth Estate let run amok for years, selling debt securities that put the entire financial system at risk. The dangers of Credit Risk Pollution produced by these securities was evident in 2006, in plenty of time to prevent the financial system wreckage that occurred years later.

Here on iTulip we refuse to play along and use the term Global Financial Crisis. The American Financial Crisis, or AFC, originated in the U.S. then spread to the rest of the world -- and still dogs it. One cannot grasp the meaning behind gold's rise since 2001 without first acknowledging that the conditions of the American political economy which gave rise to the AFC are driving gold prices higher.

Drivers of Global Monetary Regime Change

In the wake of the AFC, gold prices surged but not for the reasons that Nouriel Roubini, George Soros, and others claimed on the pages of the WSJ and the NYT at the time. The surge was not a consequence of retail investors panicking out of stocks and bonds into gold. In fact, the gold price plunged in the heat of the liquidity panic early in the AFC as retail buyers and hedge funds sold gold to raise cash. The price rise that followed the AFC reflected a new stage in global monetary regime change which began in 2001.

In theory, the world’s major reserve currency used in international trade need not be backed by a commodity such as gold as it was from the 1840s until 1971 when U.S. Treasury bond became the world’s monetary reserve asset, and the U.S. dollar the unit of that reserve.

If a single nation among all nations meets the following criteria, it can issue the world’s reserve currency and be trusted to maintain the value of that currency if it meets at least these three criteria:

1. World’s largest GDP and tax receipts to match to back its promises

2. World’s most liquid and transparent bond market

3. World’s most trusted and disciplined Central Bank with respect to maintaining low inflation and ensuring financial market stability

My choice of the phrase “World’s most” rather than some absolute measure conveys the reality that with respect to maintaining the authority to issue the world’s reserve currency credibility is relative. 2. World’s most liquid and transparent bond market

3. World’s most trusted and disciplined Central Bank with respect to maintaining low inflation and ensuring financial market stability

The bond market need not be perfectly liquid and transparent nor the central bank perfectly trustworthy and disciplined, only that these be significantly more in evidence for the country issuing a reserve currency than for the other members of the monetary system who are parties to it.

The technology bubble was, in my opinion, the firing gun that communicated to other participants of the global monetary system that systemic and possibly venal corruption had infected the world’s reserve currency issuer.

Foreign institutional and official market participants began to respond rationally to evidence that in addition to the fact that the U.S. no longer held a dominant share of global output, U.S. leaders and institutions were taking on the unseemly character traits and behavior of their own.

They began to think, “If I want to put my money into a corrupt and unreliable banking and financial system, I can keep it here at home. I don’t need to bother with the U.S.” Paradoxically, at the same time, in countries such as Brazil, technocrats trained at U.S. universities were applying the very U.S. principles of market transparency and efficiency that the U.S. was abandoning.

As the global monetary system based on U.S. Treasury bonds does not have an official Plan B should the system fail, the unofficial Plan B has always been gold. At least that was my theory back in 2001. In 2001, with the crash of the stock market bubble the U.S. began to lose its legitimacy as the world’s reserve currency issuer and gold prices began to rise.

Global investor epiphany

In 2009 the AFC accelerated the global investor awareness of this new, more unseemly character of the American political economy.

Gold as fallback reserve currency was to my mind in 2001 the only rational argument available to explain why central banks continued to hold more than 20% of all of the gold ever produced in history as reserve assets 30 years after gold was officially de-linked from the global monetary system.

Readers who have been following along with my theory of gold since 2001 were not surprised to find that starting in Q2 2009, in the wake of the AFC, global central banks became net buyers of gold for the first time since after WWII.

How much longer can the tail of the global economy wag the global money system dog?

The U.S. no longer dominates the world economy as it did when the global currency arrangement was created.

This brings us back to the matter of mainstream media coverage of gold. Starting in 2009, the anti-gold checklist disappeared from articles in the mainstream media about gold.

After the AFC, imploring investors to avoid gold for checklist reasons was no longer credible.

With interest rates pushed to near zero to reflate the economy after the crash, no one cares that gold does not earn interest.

The AFC made the public intensely aware that the stock market in inflation-adjusted terms has declined by double digits over the past decade while gold increased five-fold, steadily, year after year, demolishing the argument that gold always performs worse than stocks over the long term.

Stock market volatility between 2001 and 2009 was so extreme it made gold price movements look tedious.

It also became painfully clear that faith in the single family home as a foolproof investment had collapsed along with the housing bubble.

Today, newcomers to the gold market who look to the pages of the Wall Street Journal and the New York Times for insight into the meaning of gold are no longer accosted with a stream of anti-gold propaganda but are still treated to the occasional article warning that gold is a dangerous bubble, yet even instances of these dubious warnings grow rare as it dawns on the public mind that the bi-annually predicted impending gold bubble collapse has failed to materialize for more than five years.

That still leaves a tangle of confusing motives and viewpoints charged with emotion. Gold may not be magnetic, but it attracts passionate opinion as no other asset class can.

Politics of Gold

Pity the neophyte as he or she first enters the world of gold as a financial asset. The newcomer thinks of gold as a rare, soft, beautiful yellow metal used in jewelry to embellish souls or in electronic circuits to protect parts against corrosion. Enter the brawling gold investment forum and suddenly gold takes on a thousand colors.

To the true believers gold is at once a symbol of righteousness and honesty, a beacon of light to lead a lost people from the badlands of government-made money, a solid moral anchor for a errant relativist culture, and a personal financial life raft to float the family homestead in a tsunami tide of economic destruction when the inevitable Day of Reckoning arrives.

The true believers have a name. They are called gold bugs.

On the other side of the argument are equally ardent gold detractors, many of whom vilify gold as fervently as true believers glorify it. The vehemence of their arguments against investing in gold belies the self-doubt that arises from not knowing how to answer the question: “Why did I remain in the stock market and keep faith in a conspicuously manipulated financial system for so long? Why have gold prices gone up every year since 2001 while stocks fell? Why didn’t I buy gold when the price was lower?”

The silent self-flagellation that occupies millions of prospective gold investors is unjustified. To a far greater extent than they may be willing to accept, the misinformed condition of the American investors’ mind with respect to gold investment, which condition led to the decisions they made, is not entirely their fault.

Discussion of gold as an investment has become a crazed team sport divided between passionate fanatics and correspondingly vehement detractors, with an irritable audience of mainstream investors in the stands scratching their heads, wondering what all of the fuss is about.

In their defense, the mainstream business media struggles to find credible, independent sources of gold market knowledge. The views of the most knowledgeable are the most suspect for being the least dispassionate.

Who but a Dodger’s fan can cite each player’s record of assists, double plays, and errors, and who but a gold bug can cite the last time gold prices previously spiked and fell on a percentage basis as much as between August 1 to September 30, 2011 and why?

Perversely this credibility gap means that the less you know about gold, the more trusted you are as a dispassionate source. In fact, in order to qualify as a true gold expert you need to know nothing about it whatsoever.

That leaves the hapless retail buyer left to read the opinions of either the fanatical or the benighted. Each provides a belief-specific awareness filter on the facts.

For example, a gold bug will tell you that gold was illegal for Americans to own from 1933 until 1974, which is true, but then he will spin this into a tale of government goons cracking open safe deposit boxes to confiscate gold. The fact is that that the law was so weak that it was enforced only once in 40 years, and that single case was dismissed.

The truth of the episode of the gold's 41 years as contraband is more interesting than the conspiracy theories. The majority of gold investors, who become known as gold hoarders whenever the government needs it, turned in gold voluntarily before the May 1, 1933 legal deadline set by FDR’s order. They did so for largely patriotic reasons, to help rescue the economy that had been in a deflationary death spiral for three years under the non-leadership of Herbert Hoover.

Sixty-five years later, in the depths of the Asian Currency Crisis in 1998, without force of law millions of Koreans scraped together more than a billion dollars worth of gold jewelry, coins and other personal items to give to the government voluntarily to be melted down to shore up the central bank's reserves. To put this egalitarian behavior into context, thousands of Korean college students had to go home to their families in Seoul that year from the U.S. because the won had so depreciated that savings in domestic bank accounts could not cover tuition. City parks filled with the unemployed when only months before unemployment was largely unknown. It was a classic Sudden Stop event (see Headed for a Sudden Stop, 2008). The populace rallied in the nation’s time of need, turning in gold to shore up the system for the greater good.

This nuanced interpretation of gold's function in a currency crisis is critical to get right because it suggests how the latest episode in the life of gold as a monetary asset is most likely to end. Rather than by government confiscation as gold fanatics warn, I have argued since 2001 that the most probable endgame is for global monetary crisis to force the U.S. to re-open the gold window, a concept I explain in detail later, with gold turned in by U.S. citizens voluntarily to increase U.S. holdings from 8,133 tons today to enough to truly back the full faith and credit of the U.S. Treasury.

Gold as Protection Against the Causes and Effects of Global Monetary Regime Change

My investigation into gold starting in 1998 and culminating in 2001 with a major purchase focused on an anomaly of central banks and national treasuries: they publicly proclaimed gold irrelevant while they continued to hold in excess of 20% of all of the gold ever produced. Not only that, but the distribution of gold reserves struck me as geopolitically telling.

The United States with 8,134 tonnes has by far the largest gold reserves, followed by Germany at 3,401, the IMF at 2,814, Italy at 2,452, and France at 2,435. Altogether the world's governments own 30,407 tonnes. Thirty thousand tonnes struck me as rather a lot of anything for governments to own that they collectively profess has no value or purpose. The question, then, was what value and purpose does gold still have in government vaults? Answer that question, I told myself, and I can forecast where gold prices are going to go.

One way to approach the question is to investigate how gold got into the government vaults in the first place. It didn't appear out of thin air. The history was undoubtedly long and complex, but at the heart of it were principles that hold throughout the ages.

Essential Trends - Part I-B: Gold in an Era of Global Monetary System Regime Change

The history of our modern world is written in the gold reserves holdings chart above. I will not attempt to cover all of the ebbs and flows of gold reserves of 35 nations between 1845, through the global financial crisis of the 1860s, WWI, and WWII. The obvious point that this chart makes is that the U.S. has since the end of WWI held far more gold than any other country. Also, measures to collect gold from U.S. citizens were highly effective at expanding national reserves.

The second largest national gold reserves during this period were held in the vaults of The Bank of France. If you take the U.S. out of the picture, gold reserves over the same period looks like this, with France dominance beginning in the 1860s until the 1890s when the Bank of Russia kept up with French gold reserves until the Russian Revolution. (Continued... $ubscription)

iTulip Select: The Investment Thesis for the Next Cycle™

__________________________________________________

To receive the iTulip Newsletter or iTulip Alerts, Join our FREE Email Mailing List

Copyright © iTulip, Inc. 1998 - 2009 All Rights Reserved

All information provided "as is" for informational purposes only, not intended for trading purposes or advice. Nothing appearing on this website should be considered a recommendation to buy or to sell any security or related financial instrument. iTulip, Inc. is not liable for any informational errors, incompleteness, or delays, or for any actions taken in reliance on information contained herein. Full Disclaimer

Comment