Enlisted men tear up a flag they took from Socialist protesters in Boston, 1947

Shrinking pie politics supplants 30-year-old credit-financed fantasy of plenty

The Right Questions*

• Can the US economy recover?

- On the unrecoverable error of a credit-financed economic boom

• Can the US escape its output gap trap?

- On perpetual output gaps, structural unemployment, and a history of violence

• How do we allocate our portfolio during the era of uncertainty?

- On the Uncertainty Era Asset Allocation Rulebook

* Because you can't find the right answers unless ask the right questions.

Can the US economy recover?

On the unrecoverable error of a credit-financed economic boom

More Americans Think Economy Will Never Recover

Americans are growing increasingly doubtful about direction of the US economy, according to the latest survey from business-advisory firm AlixPartners.

In fact, an increasing number, some 61 percent, say they don't expect to return to their respective pre-recession lifestyles until the spring of 2014, if ever.

- Christina Cheddar Berk, CNBC, June 3, 2011

Americans are growing increasingly doubtful about direction of the US economy, according to the latest survey from business-advisory firm AlixPartners.

In fact, an increasing number, some 61 percent, say they don't expect to return to their respective pre-recession lifestyles until the spring of 2014, if ever.

- Christina Cheddar Berk, CNBC, June 3, 2011

Credit Expansion, 1920 to 1929, and its Lessons

"We have undoubtedly expanded the credit structure, spending today and postponing the accounting until tomorrow. We have been guilty of the sin of inflation. And there will be no condoning the sin nor reduction of the penalty because the inflation is of credit rather than a monetary one.”

"…the area covered by credit sales enlarges and the volume of credit expansion increases. As in monetary inflation the immediate results seem favorable. Credit expansion results in business activity, in full employment, in optimistic outlook and in a flood of gratulatory literature proclaiming us wiser than our predecessors. But the evidence is consistent and cumulative. The past decade has witnessed a great volume of credit inflation. Our period of prosperity in part was based on nothing more substantial than debt expansion.”

"The essential point here is that during the period of introduction of these new financial devices and while the newly opened reservoirs of credit are filling, we have a temporary increase in the nation’s purchasing power. A combination of circumstances has rendered this expansion of large dimensions in the decade just closed…”

"The check to expansion is sharp and is intensified by the excesses inevitably associated with periods of over-rapid expansion. Such a course of events is clearly proven by the evidence as to credit expansion in the period 1920 to 1929. The depression into which the nation fell in the latter year was undoubtedly due in part at least to these developments in our complicated economic structure.”

"When the accounts are footed we shall have learned new lessons respecting the evils of credit inflation. This dear bought wisdom we may place beside our knowledge of the evils of monetary inflation purchased at an equally dear price. And we may venture a pious hope that the joint lessons will induce growth of the wisdom to foresee, caution to move less rapidly and more surely in the path of progress…”

- Charles E. Persons, excerpt from “Credit Expansion, 1920 to 1929, and its Lessons”

The Quarterly Journal of Economics - November 1930

Of course the US economy will never recover from the collapse of a three decade long credit bubble. Throw ever-rising energy costs into the bargain and you have the ingredients for a perpetual decline in real per capita GDP, the ubiquitous historical antecedent of political conflict and social unrest."We have undoubtedly expanded the credit structure, spending today and postponing the accounting until tomorrow. We have been guilty of the sin of inflation. And there will be no condoning the sin nor reduction of the penalty because the inflation is of credit rather than a monetary one.”

"…the area covered by credit sales enlarges and the volume of credit expansion increases. As in monetary inflation the immediate results seem favorable. Credit expansion results in business activity, in full employment, in optimistic outlook and in a flood of gratulatory literature proclaiming us wiser than our predecessors. But the evidence is consistent and cumulative. The past decade has witnessed a great volume of credit inflation. Our period of prosperity in part was based on nothing more substantial than debt expansion.”

"The essential point here is that during the period of introduction of these new financial devices and while the newly opened reservoirs of credit are filling, we have a temporary increase in the nation’s purchasing power. A combination of circumstances has rendered this expansion of large dimensions in the decade just closed…”

"The check to expansion is sharp and is intensified by the excesses inevitably associated with periods of over-rapid expansion. Such a course of events is clearly proven by the evidence as to credit expansion in the period 1920 to 1929. The depression into which the nation fell in the latter year was undoubtedly due in part at least to these developments in our complicated economic structure.”

"When the accounts are footed we shall have learned new lessons respecting the evils of credit inflation. This dear bought wisdom we may place beside our knowledge of the evils of monetary inflation purchased at an equally dear price. And we may venture a pious hope that the joint lessons will induce growth of the wisdom to foresee, caution to move less rapidly and more surely in the path of progress…”

- Charles E. Persons, excerpt from “Credit Expansion, 1920 to 1929, and its Lessons”

The Quarterly Journal of Economics - November 1930

Current course and speed, we will see no recovery even to a hypothetical "new normal" that echoes 2007 or 1999 or 1994 for that matter.

Not by 2014.

Not ever.

The lesson for us in the observations by the hopeful albeit naive economist Charles Persons in 1930, first posted here on iTulip 11 years ago, is that the lessons of history go unheeded by politicians when the lesson interferes with the business of placating voters and making a quick buck.

Credit-financed economic booms, by turns in private then public credit as one ratchets up the other over a series of booms and busts, are as irresistible to politicians as hookers and maids.

The error of allowing another credit bubble to develop was repeated.

Policy makers are now attempting to reflate the credit bubble that started to collapse in 2008. They are squandering time and public credit that we desperately need to take policy steps that stand a chance of producing lasting economic growth by re-building the foundation of a productive America.

Our economic crisis is a credit and energy crisis rooted in the inability of our national economy to produce enough primary surplus to grow, create jobs, and also pay debts left over from a previous splurge in private and public borrowing, and also afford an energy intensive transportation infrastructure as oil import costs rise.

America is not alone with its political struggle between creditors and debtors. The political consequences of the failure to keep promises made with borrowed money are being felt in Spain, Greece, and China. The failures of American FIRE Economy policies are behind the movements in Libya, Yemen, and Syria, as reflation measures, from quantitative easing to currency depreciation, steal purchasing power from low income families world wide, acting as the most regressive tax imaginable. Simmering hatreds are exacerbated by the developing global crisis over oil supplies and costs.

Something has to give. Something will give, in my estimation within the next ten years.

I argue that the inability for the United States, the world's reserve currency issuer, cannot repay internal and external debts and absorb rising energy costs. The promise of endless growth and opportunity glued our society together for decades. We are running out of the ingredients of that glue: cheap credit and cheap oil. We are seeing a wide range of social domestic conflicts develop as budgets are cut and at the same time the basis for real economic recovery diminishes.

A dozen desirable trends of the past decade will reverse over the coming years, trends that we take for granted as perpetual. They are becoming luxuries that we can no longer afford. By following the chain of causation, starting from the original sin of the credit bubble, I am led to the inescapable conclusion that this ends in global military conflict.

National downward mobility

We will not be able to afford the cost of 2.5 million incarcerated Americans. Prison populations will decline and crime rates will rise.

We will not be able to bail out retirees for trillions in unfunded corporate pension liabilities, an even bigger scandal than the unfunded public pension liabilities that are making headlines today.

We will not be able to afford 1.5 million men at arms, but we will grow this force anyway at the expense of other priorities.

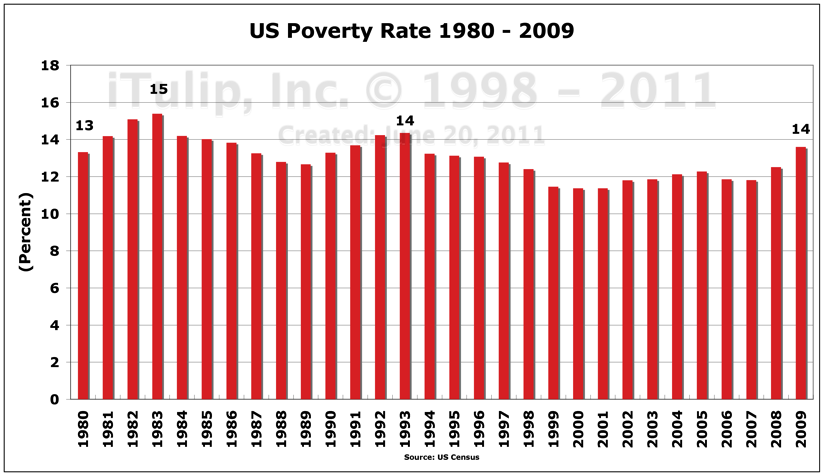

Not when we have 44 million Americans living below the poverty line, up from 29 million in 1980, 14% of the population versus the previous peak of 15% in 1982.

Not when a fifth of the US population is on food stamps.

Each time a group of retirees, or veterans, or other part of American society is sacrificed to bubble era debt repayment, society gains another few hundred thousand disgruntled, cynical, and angry citizens.

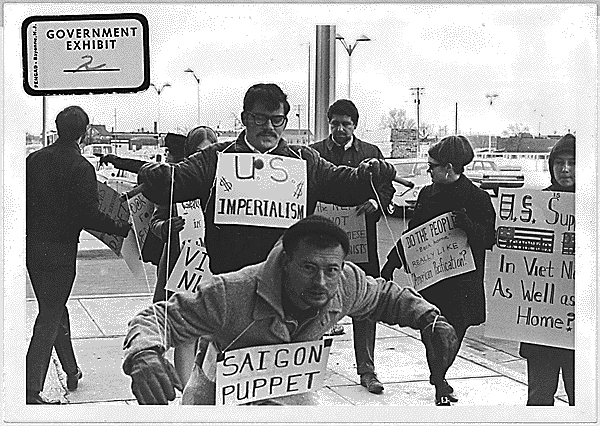

Not since the draft and the Vietnam War has public policy so divided the nation.

All macro economic trends are going in the wrong direction to reverse negative social trends.

Sliding Down the Doomer Scale

Long time readers know that since 1998 I have prided myself in making neither optimistic nor pessimistic but realistic assessments of our economic future and how to best invest for ourselves and those we love.

A survey of our members in June 2007 in the widely read article Are You a Doomer? revealed that the typical iTuliper is neither optimistic nor pessimistic. On our 1 to 10 iTulip Doomer Scale, the average of several hundred survey participants came in at 5.

At the time, I was forecasting a massive financial crisis and recession as fallout from the collapse of the housing bubble. That no doubt struck our more optimistic members as excessively doomerish.

After completing this analysis, I warn the more optimistic among you that I am moving closer to a 3 on the scale.

This time it is my unfortunate duty to inform the iTulip community of my bleak assessment of prospects for investing over the next ten years. I draw this conclusion after three years of investigation.

This analysis took far longer than I expected. Once you read it, I think you will understand why.

The project began in 2008, after the results of the so-called financial crisis became apparent, as I was writing my book The Postcatastrophe Economy: Rebuilding America and Avoiding the Next Bubble

.

. Today, looking out over the next ten years as I did in 2000 when I took positions in gold and Treasury bonds, I see the dissolution of the US FIRE Economy and the social structures that developed around it. As the US is the largest economy in the world, the implications for the rest of the world are profound.

As investors, the next decade will be nothing like the previous one. The second failure of globalization will produce a volatile and unpredictable environment for capital markets.

As grim as the past decade was for US stock market investors, prospects for stocks in the coming decade are even worse.

The last decade was good for investors in commodities, gold and Treasury bonds, but unlike the relatively steady rise in gold prices that we experienced since 2001, capital will surge among countries and asset classes in response to events, searching for safety, not yield.

The US will continue to be viewed as the safest country for investment, even if real growth is negligible, non-existent, or negative. The dollar may benefit for extended periods before the transformation to a new multilateral currency system solidifies, based on Asian, European, and American currency blocks.

It will not be possible remain in one position immobile as we were able to between 2001 and 2011. We cannot bite off the decade in one piece. We have to break it down into episodes and devise a means for making investment decisions based on rules that apply. Next we set the stage.

How did we get here?

In 2009 we escaped a repeat of a deflation spiral we experienced in the 1930s, but a repeat was never a possibility as I explained here since 2006: without the constraint of the gold standard on the Fed's balance sheet, the Fed is free to expand its balance sheet infinitely to stop deflation in its tracks -- and did.

Unlike the 1930s credit bubble collapse episode, the Fed plugged the hole in the cracked credit structure with creative accounting, using policy measures that were unimaginable except to those of us who bothered to read Bernanke's published plans to prevent a repeat of The Great Recession, to make sure "it" -- referring to a 1930s deflation spiral -- doesn't happen here. But he also meant deflation as occurred in Japan due to a persistent output gap produced by a post credit bubble recession and debt deflation. Bernanke wanted to make sure that our post crash output gap was manageably small. To achieve that took extraordinary measures that the Japanese central bank failed to take in the early 1990s. The Japanese have battled the output gap that resulted from those first years of fumbling ever since. As it turns out, even the relatively small 4% of GDP output gap that the so-called Great Recession produced was too much.

In the short run, Bernanke succeeded. In the long run he will fail.

Instead of writing papers since 1984 about how to manage a post credit bubble credit crisis, Bernanke should have been writing papers about the evils of credit bubbles and how to avoid them.

Proposed emergency policies included buying long dated government bonds to “shape the yield curve,” known as government bond price fixing in less polite circles. Another scheme offered was to disappear worthless commercial paper held by banks via the accounting gimmick of listing the worthless securities on its balance sheet simultaneously as both assets and liabilities.

Presto! They're gone! It's a miracle!

No one has to take a loss.

And so it is as Bernanke did when the crash came. I think of his Princeton papers on The Great Depression as a job application for head of the Fed, post-Greenspan.

But some day, perhaps in January 2013, a new US political administration will come clean, as the new Greek administration of Georgios Papandreou did in early 2010 when it announced: Gosh! Look at all of the accounting tricks previous administrations have used and lies they've told about our fiscal position! We're shocked! Shocked by the fiscal malfeasance! And even though we are ostensibly socialists, we're going to take on the odious task of making sure the banks are paid at the expense of the people who elected us.

At which point the Greek debt crisis and concomitant social crisis formally began.

Until that hour of debt epiphany arrives for the US, politicians can celebrate the fact that the Fed and the White House did not let the economy shrink for three years and dig itself into a 25% of GDP output gap hole as the Hoover administration and the Federal Reserve under Eugene Meyer did between 1930 and 1933. As they dawdled and blundered, Hoover and Meyer compounded the error of the 1920 to 1929 credit bubble with the banker-friendly decision to keep the gold standard going after the bubble collapsed.

The gold standard is, in a phrase, a system of gold price fixing by the government. It favored creditors who benefit when the unit of debt repayment gets stronger. This was replaced by a system of government bond price fixing, which favors creditors if the central bank succeeds at keeping the unit of debt repayment strong and adds the special favor of interest income on reserves. History will teach us again which system works better for the American people.

Stimulus measures applied by Ben Bernanke's Fed and the Obama administration were immediate and radical. They affected a quick end to the short-lived liquidity crisis.

For dramatic flourish Ben looked pale and frightened, his voice quavering, as he sat before Congress in 2008 to explain how he needed to lend billions to his future employers at JP Morgan or Goldman Sachs. Perhaps we should open an unofficial betting pool here on iTulip. Which of these two fine institutions of finance capitalism will Ben depart to after leaving the Fed to spend more time with his family, after he completes his tour duty as lead central banker of the global finance oligarchy?

Compared to the 25% output gap that grew for three years after 1930 and launched The Great Depression, the last recession left us with a modest 4% of GDP output gap. Despite its relatively small size, that gap was deep enough to trap us dangerously in a wallow of long-term unemployment and diminishing ability to finance existing liabilities, as I argue below. At the rate the economy is growing we won’t escape the current output gap, now now 2% of GDP, before the next recession opens the gap even wider.

At that point we will be firmly on a trajectory to economic and social crisis and past the point of no return. We are not yet there, but unless drastic measures are taken quickly to get growth back to 4% plus growth, as I explain in my original Output Gap Trap analysis from October last year, we will find ourselves looking back sentimentally at this period as the good old days.

Below we do a deep dive into three quarters of fresh economic data to evaluate the economy's progress since my output gap analysis last fall. Policies taken to date are not working. A fresh approach is needed, and godspeed.

Spared but Still Impaired

Radical policy intervention prevented our modern credit bubble collapse from morphing into a 1930s deflation spiral, but economic growth remains thwarted by a combination of grinding debt deflation and high energy costs for the duration.

Debt deflation happens when households and businesses pay off old debt faster than they take on new debt. Under our credit-based money system, all new money is borrowed into existence, so debt deflation implies a contraction in the money supply and monetary deflation unless the public sector steps in to borrow money into existence to compensate for the shortfall in private sector borrowing.

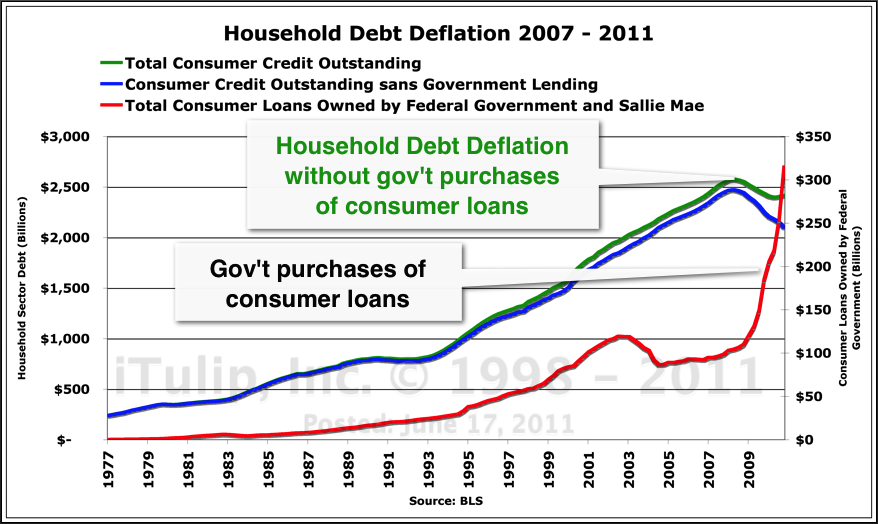

Below we see the government buying consumer loans to slow consumer debt deflation. Recently this policy stopped and reversed debt deflation in the consumer credit market, but at the cost of expanding government liabilities. This what we mean by "moving private debt to public account."

The Federal Government attempts to slow debt deflation with direct purchases of consumer loans.

These are slowing debt deflation but not quickly enough to stimulate consumption to

motivate producers to grow payrolls and generate organic consumer credit growth.

The green line in the chart above shows the result of organic consumer credit growth plus inorganic consumer credit growth financed by government purchases of consumer loans measured on the left hand scale. The red line shows federal government purchases of consumer loans rising from $100 billion to $300 billion since 2009 on the right hand scale. The blue line shows organic consumer credit growth with inorganic government-financed consumer credit growth backed out. Bottom line, consumer debt deflation will continue if the government steps out of the consumer loan market.

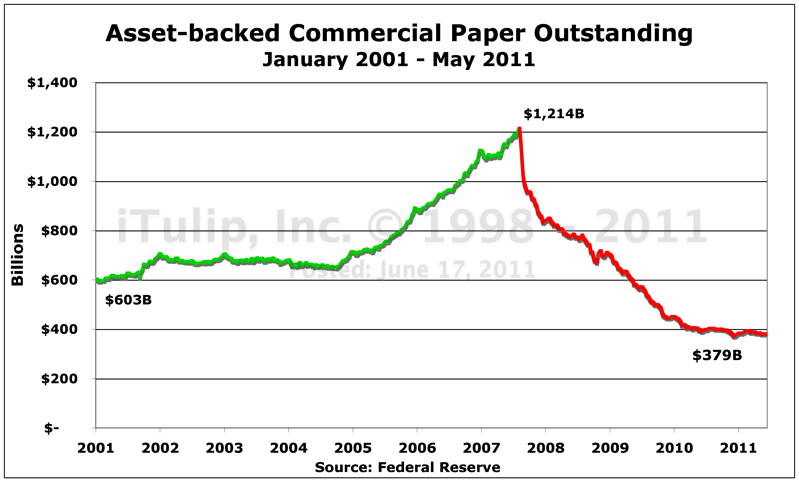

The result of government intervention in the mortgage credit market has been less effective. Mortgage debt deflation continues unabated. The poor condition of the engine of the housing bubble, the asset-backed securities market, is indicative.

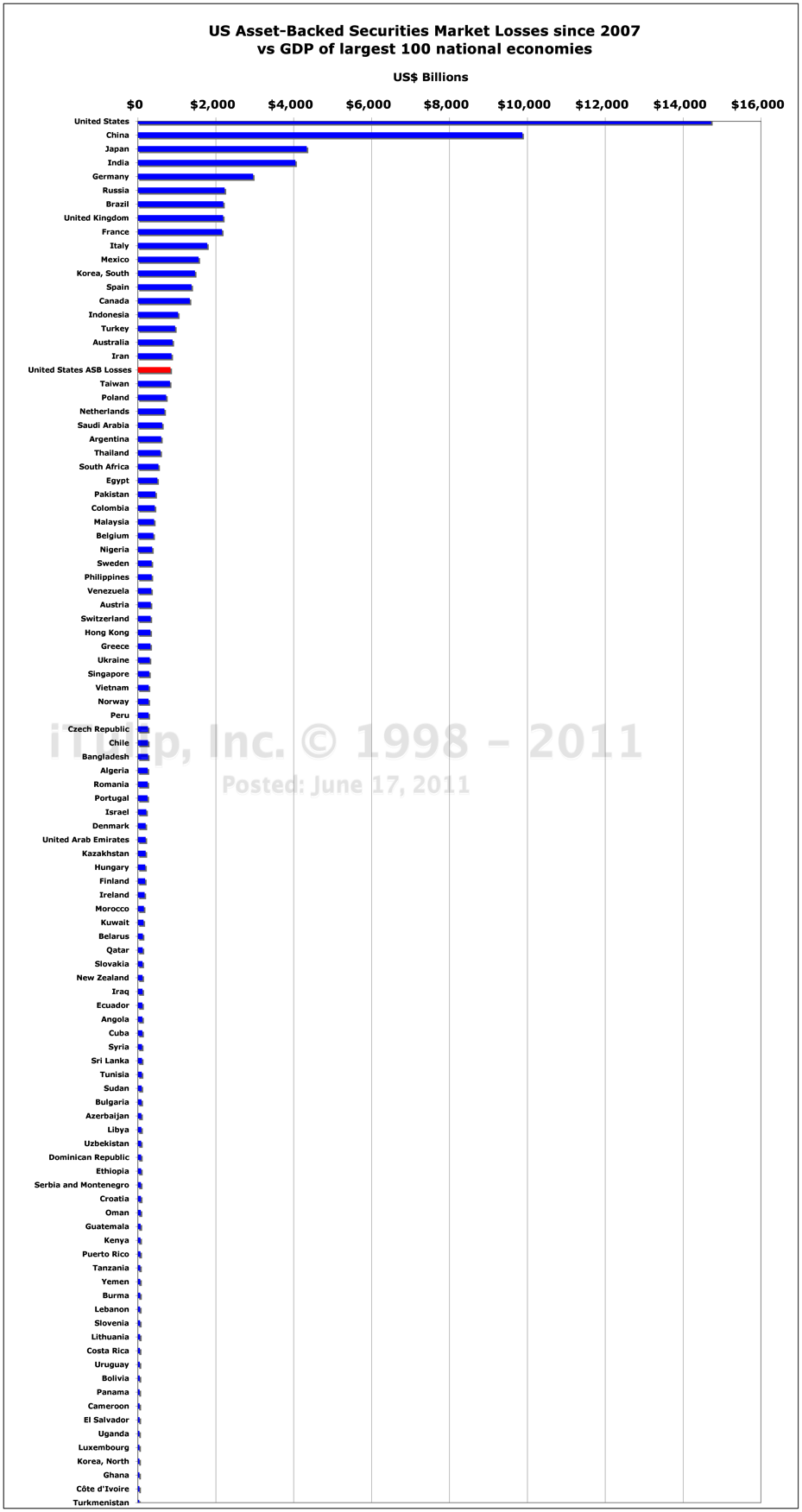

The Fed took these securities onto its balance sheet and temporarily disappeared $835 billion in paper losses. If we compare these as-yet unrealized losses in the US asset-backed securities market to the GDP of the world's largest 100 economies we find that US ASB losses come in at #19 -- between the GDP of Taiwan and the GDP of Iran.

Asset markets are resisting such heroic efforts by the government to reflate asset prices. During the hay day of the 1995 to 2006 bubble cycle sub-era of the FIRE Economy era that started in 1980, first tax revenues from capital gains on asset price inflation filled government coffers as NASDAQ speculators traded in technology stocks then happy housing speculators bought and sold condos and single family homes. No more.

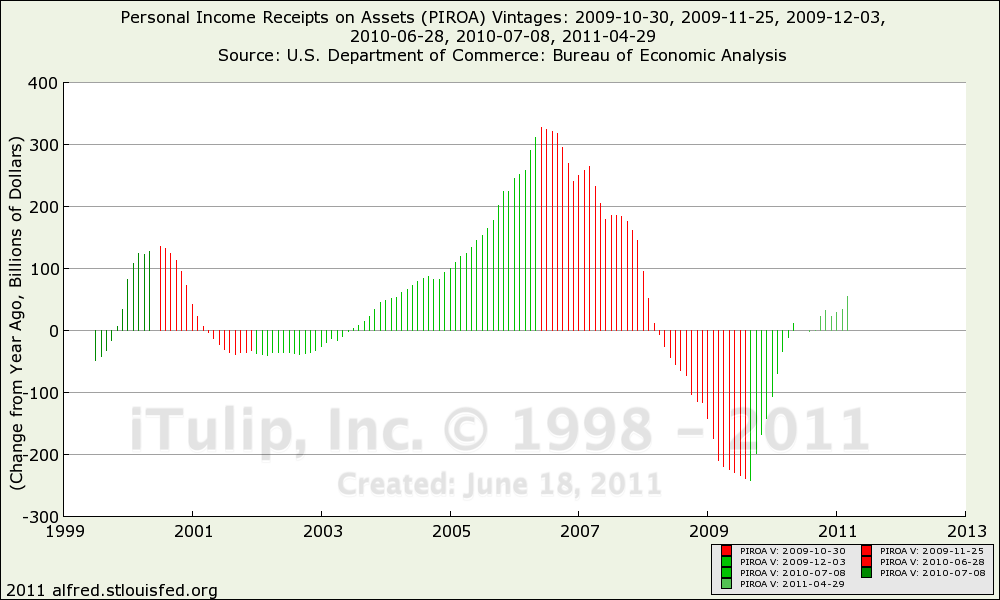

Personal income receipts on assets eked out a modest recovery, but nowhere close levels seen two years into the stock market and housing bubbles "recoveries" of the past decade.

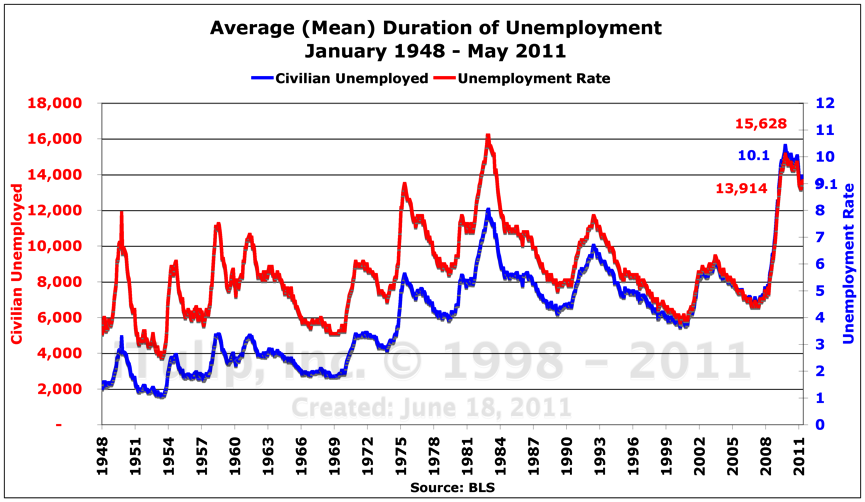

Two rounds of quantitative easing and multiple government stimulus programs prolonged the rebound, such as it is, but unemployment remains over 9%, far higher than two years into previous recoveries. By the official count, 14 million Americans are still unemployed, up by seven million and only 11% fewer than at the peak of 15.6 million. But these employment statistics are rosy compared to the picture of long-term unemployment, the hallmark of a persistent output gap.

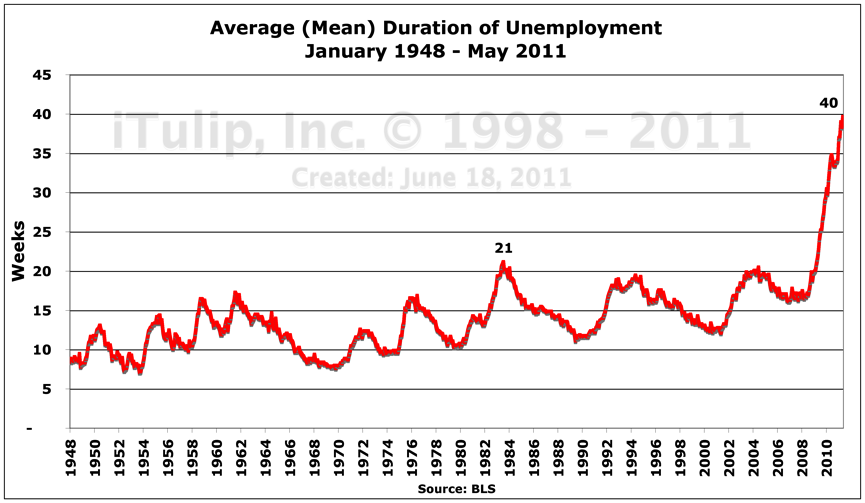

The old BLS charts that we have been using on iTulip since 1999 had to be modified because the BLS old upper limit on mean duration of unemployment was 26 weeks -- half a year. The worst previous record was 21 weeks in 1983. Mean duration of unemployment reached 40 weeks in May.

The US poverty rate is approaching it's FIRE Economy era high of 15%.

That previous 15% poverty rate resulted from an output gap that the Fed produced on purpose to kill off an inflation spiral. This time, the gap is unintended.

High unemployment is having a predictable impact on the housing market. I warned in 2002 that when the housing bubble finally collapses in a few years that housing prices will revert to the mean with a vengeance as prices correlate to regional incomes. Two years into the recovery, and five years into the housing bubble collapse, housing reveals itself to the consumer for what it is – not an asset class but a cost. Housing is only an asset class of you are a landlord or a lender.

We are at Step E of my at the time heretical January 2005 description of the housing bust process.

Step E: Five years into the downturn, rising unemployment will begin to more seriously affect the market, as indicated in Chart 1. As unemployment rises, homeowners will leave housing bust regions to move to areas where there are more jobs. Many houses will be sold at a loss, or even abandoned, as the market price falls below the loan value. Given the choice between paying cash out of pocket to sell their home or leaving the keys with the bank, many home owners will make the latter choice.

Too many houses, not enough high paying jobs

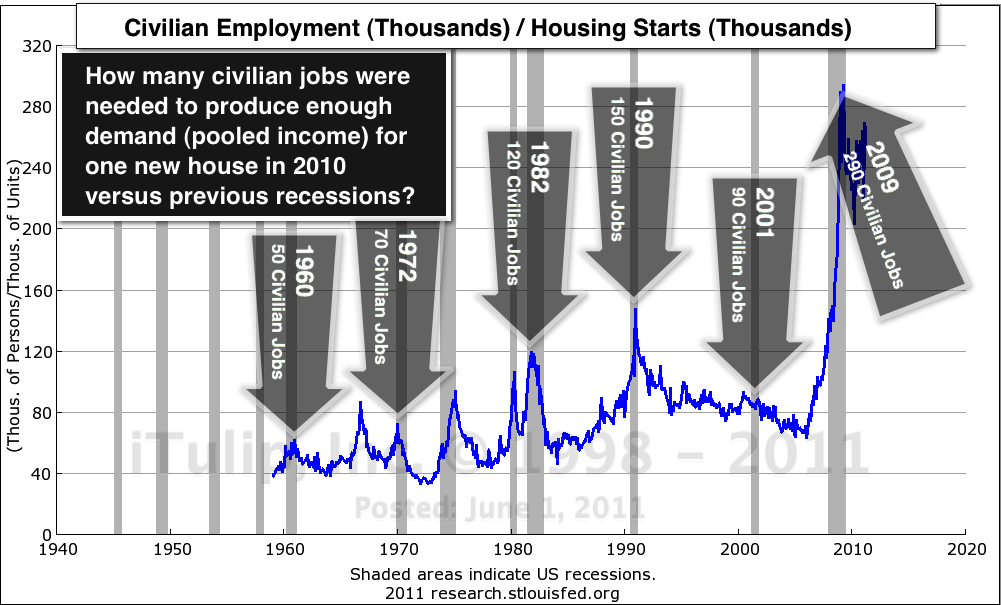

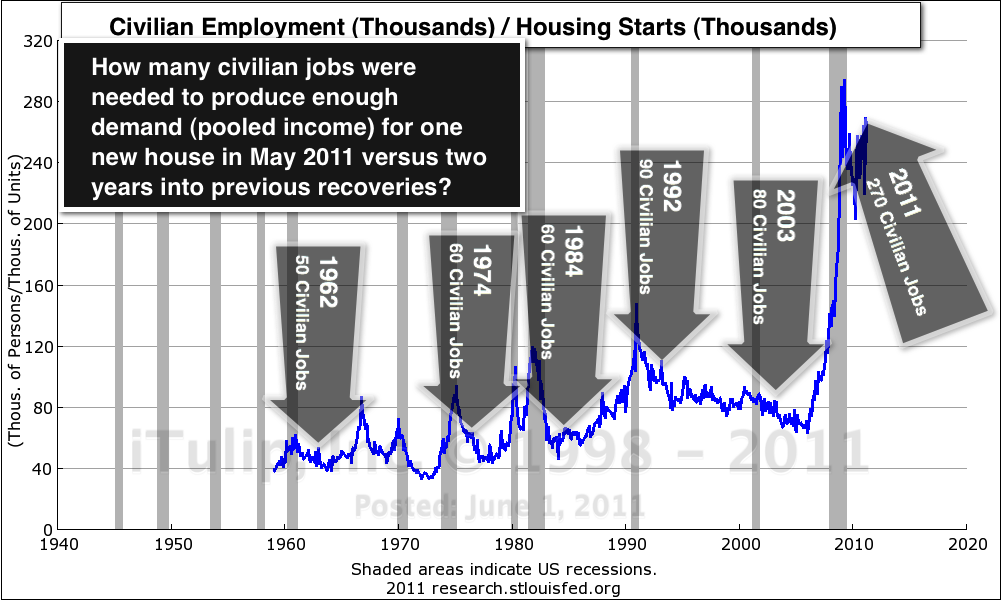

Consider this measure of new housing demand relative to employment: the number of civilian employed needed to generate enough demand to motivate home builders to build one new house.

During the worst period of the 1990 recession, 150 employed civilian workers generated demand for one new home. At the peak of the last recession in 2009, 290 employed civilian workers generated demand for one new home.

Two years into every recovery since 1960, the number of employed civilian workers needed to generate demand for one new home recovered to pre-recession levels. But two years into this recovery, the number stands at 270, only 7% below the peak of 290 and more than five times as many as in 1962.

This dreadful statistic depends on the government continuing to subsidize the monthly cost of a mortgage. Low mortgage rates are made possible by two nationalized banks, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. If these banks are privatized mortgage rates will climb into the double digits to reflect actual default risk, the monthly cost of owning a home will rise, and home prices will fall even further. If they are not privatized, they remain yet another drag on America's balance sheet, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac will eventually drive up interest rates anyway as foreign lenders demand to be compensated for default and inflation risk on US Treasury debt. Either way, mortgage rates are going up, driving home prices down.

Debt deflation results from a collapsing credit bubble. The process is not to be confused with monetary deflation, although one can be excused for conflating the two under our current system of credit-based money.

Debt Deflation without Monetary Deflation

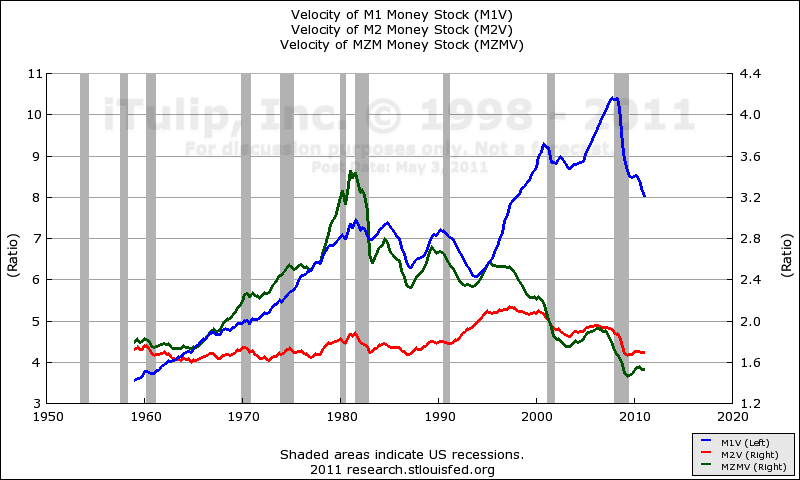

Credit and money were intertwined at the start of the FIRE Economy era in the early 1980s by the expedient of payment of interest on checking accounts. In such a credit-based money system, the money supply ceases to act independently of credit as can be seen in the chart below that shows a continuously declining velocity of money at zero maturity (MZM) since 1980 compared to interest bearing money aggregates M1 and M2.

Nominal GDP divided by non-interest bearing “money” versus interest bearing money

Central bankers worldwide appear to have agree to push the meme that inflation is transitory and will decline in the coming months. They also claim that labor markets will improve, but slowly. Tighter labor markets and falling inflation is not usually how this movie goes, and OECD economists know it. They are imploring the Fed to raise interest rates. But until the US output gap closes, and housing prices stop plummeting, the Fed will grin and bear it as inflation rises to redline levels above 5%.

Consumer Price inflation Arrives on Schedule

Reflation policy measures targeted at asset prices may have missed the mark with respect to housing prices and employment but they are having the predicted impact on the prices of food, fuel, and now finished goods. In 2009, when inflation versus deflation was a serious topic of debate, I promised you consumer price inflation by the second quarter of 2011. My theory was that due to reflation policy, in particular currency depreciation via fiscal policy and sustained negative real interest rates, would increase exports as intended but also increase the prices of imports. In 2008, during the fire sale part of the crisis, I told readers to go out and buy all of the imported durable goods they're going to need for the duration because import prices are going up. Two and a half years later, the news makes the front page of the Wall Street Journal:

Change in China Hits U.S. Purse

June 21, 2011 - Wall Street Journal

For more than a decade starting in the early 1990s, U.S. inflation declined as low-wage workers in China and other developing nations joined the global economy and produced a tide of cheap goods that washed onto U.S. shores.

The trend made American consumers feel better off and, by restraining the upward crawl of consumer prices, helped enable the Federal Reserve to fuel the U.S. economy with low interest rates.

That epoch appears to be over. Prices of imported goods are climbing, becoming a source of inflationary pressure. A wide variety of common products made abroad, from shoes to auto parts...

Further, I speculated that producers that had enough cash to live through the wave of bankruptcies in 2008 and 2009 to remain as the survivors in their respective industries were set to gain pricing power even if aggregate demand had fallen below pre-recession levels. For example, instead of 20 high end restaurants vying for 1000 customers in a 10 mile radius, now 10 high end restaurants vie for 750 customers, as 250 of their old customers are now eating a lower-priced eateries. June 21, 2011 - Wall Street Journal

For more than a decade starting in the early 1990s, U.S. inflation declined as low-wage workers in China and other developing nations joined the global economy and produced a tide of cheap goods that washed onto U.S. shores.

The trend made American consumers feel better off and, by restraining the upward crawl of consumer prices, helped enable the Federal Reserve to fuel the U.S. economy with low interest rates.

That epoch appears to be over. Prices of imported goods are climbing, becoming a source of inflationary pressure. A wide variety of common products made abroad, from shoes to auto parts...

Welcome to the new inflationary era of the Postcatastrophe Economy.

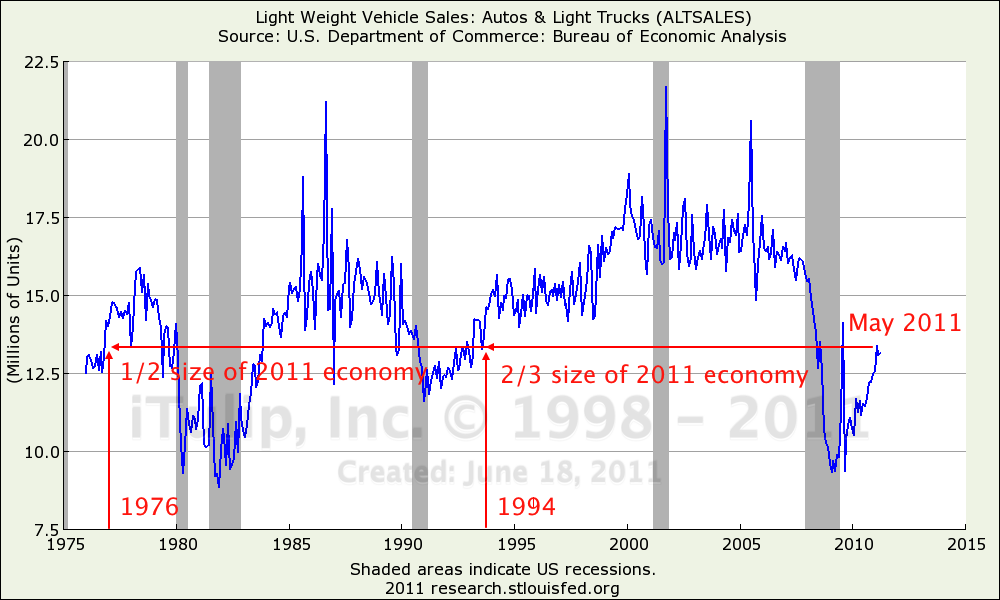

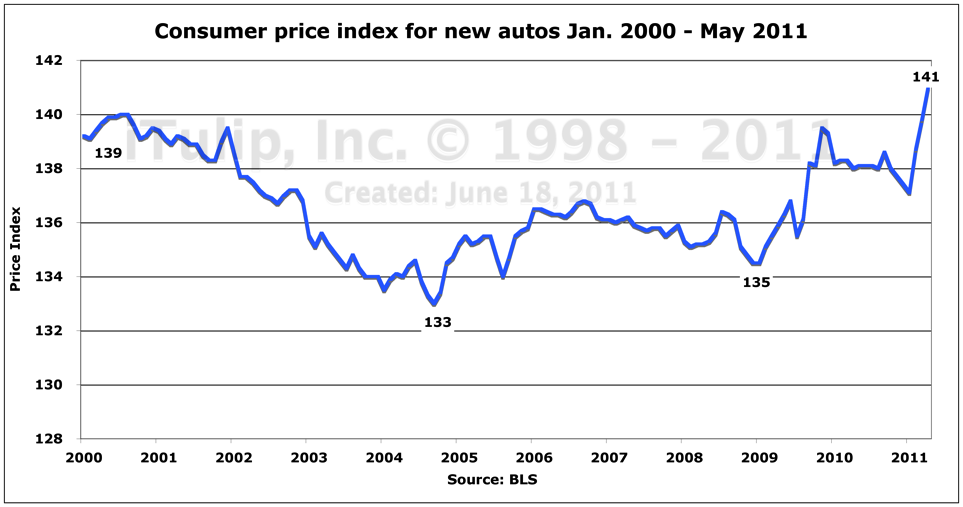

After falling to the 1983 recession level, sales of passenger cars and small trucks have recovered to the 1994 level, when the economy was 2/3 the size of today's, also a level first seen in 1974 when the economy was 1/2 the size of today's. Despite this tepid demand, auto prices are rising. In fact, inflation has been more rapid over the past two years than over any previous two year period in history.

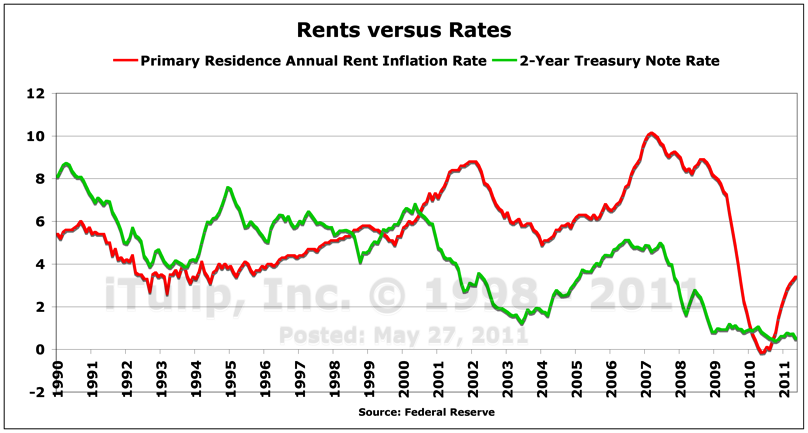

Apartment rents, a historical harbinger of broad-based consumer price inflation, have also climbed steeply, happily in line with the theory of our investment in Eastham Capital's multi-family housing fund last year. With interest expenses low and rents rising, the environment for improved cap rates couldn't be better.

Deflating asset prices and inflating goods and services prices is the price of policies pursued by the current administration to avoid the inevitable occurring on their watch.

Promises have been made and promises will be broken. Not only the promises to government workers who paid into their pensions for a lifetime, but to savers generally.

The Road to Perdition

The majority of Americans may believe that the economic crisis knocked them off their destined course to wealth and prosperity, but the truth is that we were never as rich as we thought we were when cheap credit and cheap oil expanded our purchasing power unnaturally beyond the limitations of our productivity, of minds and machines, to generate an economic surplus.

If we were honest we’d admit, like a lottery winner who has spent all his winnings on cars and drugs, that the era of free-wheeling fun has come to an end.

We had a blast, but it’s over.

At least some of us had fun. The dot com speculators who sold at the top. The housing bubble speculators who got out in time. The Wall Street investment bankers who played it both ways, selling junk on the way up and shorting it on the way down.

Too bad for everyone else, for those who missed out, for the paycheck workers and the stock mutual fund buy-and-hold investors. The losers along with the winners will have to shoulder the burden of coping with cheap oil and credit era debris. The inherent unfairness of this outcome of the credit bubble era will pose yet another threat to the long standing presumption of American political stability and security that underpins the relative safety of US capital markets.

Debt Debris

The collapsed credit bubble has left us with a debt overhang that diverts the cash flow of households and business toward payments of principle and interest, preventing our economy from reaching its full output potential. Failure to write down the bubble era debt consigns us to corrosive debt deflation that demands more government stimulus spending to keep the top line of the economy growing while eroding the bottom line -- the purchasing power of income and savings -- with cost-push inflation, an artifact of a persistently weak dollar.

Richard Koo refers to his condition euphemistically as a “balance sheet recession.” That’s banker-speak for using public funds to try to close an output gap created by the collapse of a credit bubble that enriched creditors without holding them to account. As we see later in this analysis, Japan's experiment with applying Keynesian stimulus for decades rather than for a brief period to close an output gap as Keynes intended, will be among the great economic failures that befall the world in the coming decade.

Left-leaning economists deploy semi-scientific language to argue that we need to use public funds to prop up the economy until it becomes self-sustaining. They ignore the fact that the policy only works if the private sector can be primed to borrow more money into existence than it is retiring via debt repayment, else the dependence on deficit spending becomes structural and the spending perpetual, at least until the nation runs out of credit in a decade or two.

Right-leaning economists argue for cutting government spending and taxation to free up producers to hire and consumers to spend, ignoring the fact that when an over-indebted economy is in an output gap a reduction in government spending reduces the economy's primary surplus, shrinking the economy further, either in real or nominal terms, and worsening its fiscal position. It's like a mortgage lender demanding that a borrower sell the car he needs to use to get to work, so that income that he is spending on car loan payments can instead be used to pay off the mortgage. It's self-defeating.

Once an over-indebted country in an output gap begins to have difficulty repaying foreign debt, because debt payments exceed available tax revenue net of outlays, that nation will only dig itself deeper into a hole if policy makers attempt to reduce budget deficits by means of spending cuts. According to economist Sebastian Edwards, “Perverse fiscal dynamics – where the country fails to generate a primary surplus large enough as to stabilize the debt to GDP ratio – usually generates a vicious circle, where failure to stabilize the debt ratio results in higher cost of funds, lower growth, and in an even larger required primary surplus.”

The so-called debate about debt ceilings, spending cuts, and entitlements reductions is a red herring. The public debt crisis arose from the 2007 - 2008 private credit market crisis, not the government liabilities that have been building for decades.

The mistake of both the left and the right is thinking that we can escape an output gap without facing up to the politically unpopular task of demanding that creditors take a loss on loans taken out during the credit bubble era.

We need a private sector debt cut, not a tax cut.

Trillions in mortgage debt against fictitious housing value remains on the balance sheets of households after home prices deflated 25%.

These debts should not exist. They resulted from an over-abundance of credit and deficiency in lending discipline.

But Main Street’s credit bubble era debt is Wall Street’s political cash flow entitlement.

The banking lobby will make sure that the next president and Congress keep the bogus debt service payments flowing, no matter that principle and interest payments on mortgage debt now consume 30% of the average household budget, followed by transportation costs at 19% and rising, food costs at 14% and rising, insurance costs at 12% and rising, and health care costs at 6% and rising. Throw in a value-added tax proposed by Paul Volcker and others to balance the budget and we can kiss what’s left of our Postcatastrophe Economy goodbye.

Debt deflation is not the only holdover from the cheap credit era that is keeping us stuck in an output gap. At the same time the bill is coming due for building a transportation infrastructure that is dependent on cheap imported oil.

In the short-term, high oil costs push the US economy ever closer to negative real growth territory.

In Q1 2011, consumer price inflation averaged 3% according to the MIT Billions of Prices project, while the Bureau of Labored Statistics' revised Q1 GDP number confirmed a 1.8% real annual growth rate. In the same quarter the BLS reported a 3.7% nominal GDP growth rate and an average 2.2% inflation rate. When we subtract 2.2% from 3.7% we get a real GDP of 1.5% not 1.8%, but enough quibbling. If the nominal GDP growth rate was 3.7% and we use the MIT versus the BLS numbers, we get 0.7% real GDP growth, and I estimate that in Q2 2011 the economy contracted in real terms. This is the beginning of the first Peak Cheap Oil Cycle recession, a recession in real but not nominal terms. As we see later in this analysis, real GDP recessions are far more painful and political destabilizing than the nominal recessions.

In the short run, bad energy policy is heightening stagflation. In the long run it drives destructive public policy.

Forgotten Lessons and the Repetition of Fatal Errors

The private credit crisis that gave rise to our current economic crisis is a product of the second large scale credit bubble in 100 years. Were he alive today, Charles E. Persons, quoted above, will be disappointed to find that no lessons were learned respecting the evils of credit inflation, and that the dear bought wisdom of the 1930s was not placed beside our knowledge of the evils of monetary inflation, that in fact the wrong lesson was learned. The lesson, to avoid credit bubbles, was lost of the Greenspan Fed. Instead he believed that the flow of payments from the debtors to creditors is sacrosanct. His successor, Ben Bernanke, believes that credit bubbles can, once collapsed, be reflated with taxpayer money, to keep the payments flowing. In fact, that's why he got the job, because he'd been advertising himself for it in papers he was writing at Princeton as early as 1984.

The final lesson we shall re-learn is that there is no escape from the consequences of a credit bubble.

Sooner or later, accounts are settled. Someone has to take a loss.

The way we're headed that someone will be, as usual, the most politically vulnerable, those with the weakest political and intellectual defenses, and the loss will be taken in the form of lost purchasing power, as has been my position here since starting iTulip in 1998.

The evils of credit inflation were forgotten. Debt deflation follows the repeat of the credit bubble error. Consequent crises are following in train. We are about to re-experience a period of history that failed to teach us even more important lessons, about monetary inflation, about the social contract between the state and the citizen, about the sanctity of the principle of fair access to opportunity, and about the essential need of citizens to be treated respectfully, and what happens if these are lost.

The WWI opened on horseback and closed with steel clad tanks propelled across battlefields by internal combustion engines running on gasoline, and airplanes bombarding troops from on high, their internal combustion engines whining overhead. Oil, more than any other factor, extended WWI and exploded the scale of human losses by pitting the energy density of oil against the soft tissues of men organized for battle as they had been for millennia. As the war dragged on, the mad internal logic of technical innovation in war expanded the slaughter beyond imagination. The mad innovation continued through WWII, culminating the most insane weapon of all, the atomic bomb that blasted a city of human beings to bits.

WWII ran on oil, and was lost by nations who lost access to oil, and generations of prosperity was won by those who secured access to it, at the expense of the citizens of the countries where the oil resides by geological happenstance. While WWII was not about oil per se, the most lasting and valuable spoil of WWII was access to oil by America and its allies that guaranteed economic growth unimpeded by interruptions in oil supplies. As we see in the second part of this analysis, oil price volatility is sand in the global economic apparatus. At times over the next ten years, that apparatus will grind to a halt. WWIII will most certainly be fought over oil, but for economic survival not for economic advantage.

To the hopeful, anti-government movements in Egypt, Syria, Libya, and Yemen are the leading edge of a new enlightenment, and era of openness and freedom. Without question, such a era is deserved by the Arab world. But my reading of history and events brings me to a very different conclusion.

If I have learned anything from doing economic analysis here on iTulip for the past 13 years it is that governments learn nothing. One mistake leads to another. Mistakes become institutionalized.

From where I sit, I see the machine of global political economy churning its way inexorably toward a third world war, its institutions of diplomacy mired in cold war era thinking. Our global elite is as unsuited for the form and scale of the task at hand, for bringing nations together in a period of social stresses induced by self-inflicted economic crisis, as it was in the 1930s. Peak Cheap Oil only complicates an already impossible diplomatic task.

The mass protests in Spain, Greece, and China, the battles between rebels and repressive states in Egypt, Syria, Libya, and Yemen, and rising gang violence in the US are the leading edge of a new incivility. Political security, the foundation of efficient capital markets, will decline over the next ten years.

The task of forecasting the next ten years, with all of its uncertainty, is insurmountable using the methods I employed between 1998 and 2001 to determine to buy and hold gold and Treasury bonds for ten years. That allocation worked out like this, as my friends Paul and Wes Karger at Twin Focus Capital Partners determined by plugging the allocation into a standard benchmark portfolio allocation.

The fundamentally changed dynamics of the next decade required me to develop an entirely new way of thinking about and analyzing the political economy. Whereas the cycle of asset price inflations, deflations, and reflations drove my forecast in 2000 for the decade that just closed, the primary factor of asset allocation for the next ten years is uncertainty itself. It demands a rules based analytical method that breaks the problem down into manageable parts. Next we get started on developing our 2011 to 2020 Uncertainty Era Asset Allocation Rulebook starting with a detailed analysis of the US Output Gap Trap and its implications.

Always Watching

The Next Ten Years – Part II: Fight or flight

Investing in a period of political instability and social trauma

The Right Questions:

• Can the US escape its output gap trap?

- On structural unemployment and a history of violence

• How do we allocate our portfolio during the era of uncertainty?

- On the Uncertainty Era Asset Allocation Rulebook

Can the US escape its output gap trap?

On structural unemployment and a history of violence

To stimulate or not to stimulate? That is the question as framed by the mainstream business media. But it is the wrong question because either way the US economy sinks.

Stimulating the economy with increased government spending or via tax cuts that increase the budget deficit, or a combination of tax cuts and spending cuts that is budget neutral, will slow the US economy because it is stuck in an output gap. The output gap was created by the 2008 to 2009 recession. The dual drags of debt deflation and Peak Cheap Oil are together acting as a brake on growth.

We are in a race to close of the Postcatastrophe Economy output gap before the next recession widens it further. Current course and speed, because of the dual drags, we aren't going to make it.

The only solution is a debt cut, but that's not going to happen. So what is going to happen? more... ($ubscription)

__________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ ________________

For a concise, readable summary of iTulip concepts read Eric Janszen's 2010 book The Postcatastrophe Economy: Rebuilding America and Avoiding the Next Bubble

.

.To receive the iTulip Newsletter/Alerts, Join our FREE Email Mailing List

To join iTulip forum community FREE, click here to register.

Copyright © iTulip, Inc. 1998 - 2011 All Rights Reserved

All information provided "as is" for informational purposes only, not intended for trading purposes or advice. Nothing appearing on this website should be considered a recommendation to buy or to sell any security or related financial instrument. iTulip, Inc. is not liable for any informational errors, incompleteness, or delays, or for any actions taken in reliance on information contained herein. Full Disclaimer

Comment