220 kilogram (485 pounds) gold bar, Jinguashi Gold Ecological Park, Taipei County, Taiwan, April 2011

Reached an all time peak value of $11.64 million on April 21, 2011

Photo Credit: Eric Janszen

Global Monetary Meltdown - Part I: The accident that won't wait to happen

The Fukushima Daiichi nuclear facility helped meet Japan's need for cheap electrical energy when it was completed in 1971. The US Treasury bond-backed dollar met the world's need for a monetary anchor after the US shut the gold window the same year, bringing the international gold standard to an unceremonious and untimely end. In both cases safety was forsaken for political expediency. Both were accidents waiting to happen. One just did, and the other could happen at any time.

• The Fukushima Daiichi of monetary systems

• Not even a "service economy"

• Cold War II

"Gold is the enemy!"

- Paul Volcker (replying angrily to a question about the role of gold in monetary reform at a conference in October 2010)

"My efforts to prevent closing of the gold window--working through Connally, Volcker, and Shultz--do not seem to have succeeded. The gold window may have to be closed tomorrow because we now have a government that is incapable, not only of constructive leadership, but of any action at all. What a tragedy for mankind!"

- Arthur Burns, Federal Reserve Chairman, Aug. 12, 1971, The Secret Diary of Arthur Burns

What should we make of our precessing world? From my recent travels to Asia, Europe, and across US, and from conversations with contacts around the world, the picture is at once promising and terrifying. Thus begins a long series I've titled "Global Monetary Meltdown." This is Part I of N, the first of an indeterminate many, that tracks the progression of processes that I started to explain here since 1998, as we get down to the short strokes in the final years.

The end cannot be but two years off at most. Our outmoded US-centric monetary system and debt financed FIRE Economy are disintegrating under the weight of inflation taxes that are a consequence of private sector debt bailouts, the moving of private debt to public account, and a rigidly distorted energy infrastructure that depends on cheap oil. The final stages, that we hedged with gold bought in 2001 at $265 per ounce, are upon us.

At times I will post to this series frequently as events unfold fast and furious, when the system shakes and staggers to make headlines as it did in 2000 and again in 2008 and 2009, and less often when the underlying channels of transition shift below the surface, as the evolving monetary crisis escalates and de-escalates, but always tending toward dissolution. There is a time for analysis and reflection and another from expression. My posts shall match the cadence of global monetary entropy.

- Eric Janszen, April 2011

CI: You were in Hong Kong, Taiwan, Japan, and California, and before that you gave the keynote address to a group of power utility CEOs in Phoenix, Arizona, including several who run nuclear power plants. Before that you were in Connecticut to give the keynote to the largest and oldest international commercial real estate association. We got lots of catching up to do. Where do we start?

EJ: With our theme, the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant disaster and its analog, the global monetary system.

CI: Why go to that part of the world then?

EJ: The trip was planned well before the earthquake, tsunami, and nuke plant disasters. If I thought I was at risk, I’d have canceled. By coincidence, I gave a keynote the week before at the American Public Power Association conference just as the nuke plant crisis was starting. I could easily tell which of the CEOs in the audience, of the 80 utilities represented there, ran nuclear plants. There were the ones running out of the room every ten minutes to talk to the press and hold conference calls with their colleagues in Japan. The first week was a nightmare, but after that I went ahead with the trip. That said, I’m not eating Japanese sushi just yet.

CI: Did you see a cover-up from the start?

EJ: When the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant disaster started, the day I gave my speech, you could see the global nuclear industry circling the wagons, as they do whenever a disaster occurs. Information on the true extent of the crisis has been keep within confidential industry circles and still is. Only via forensics by independent parties has the public received information describing a reasonable approximation of actual events in real time. It’s basically the same problem we had getting accurate reports on the condition of financial institutions and banks before and during the financial crisis. Partly the under-reporting of the crisis at Fukushima Daiichi was legitimate, to limit public hysteria that would have complicated emergency response efforts to prevent a truly apocalyptic disaster, and partly to limit damage to the reputation of the nuclear power industry. I got inside that circle briefly when the danger was still critical, but the information I have is dated now that the most critical phase of the crisis has passed, although huge issues remain. I shared then what I could at the time behind the pay wall and not in public, as much as I could without violating the confidence of my sources.

CI: When did you speak?

EJ: On the morning of March 13. The news that morning was about the hydrogen explosion in Reactor Building #1. It was generally reported this way.

Tokyo Electric Power Co. said an explosion near the No. 1 reactor at its Fukushima Dai-Ichi nuclear power station destroyed the walls of the reactor building and injured four people. A hydrogen leak caused the blast, which didn’t damage the steel chamber, Chief Cabinet Secretary Yukio Edano said.

Radiation levels in the area dropped after the blast and have “now settled at a low level,” Edano said at a briefing in Tokyo today. Asia’s biggest utility “has decided to fill the containment with seawater.”

The reactor at the Fukushima Dai-Ichi plant may remain shut for a year, Seth Grae, chief executive officer of Lightbridge Corp., a nuclear energy consulting firm whose staff previously inspected the Fukushima plant, said March 11 in an interview with Pimm Fox on Bloomberg Television’s “Taking Stock.”

Makes it sound like the walls came off in a controlled fashion, that a small, temporary leak occurred, and that everything was under control. In fact, the hydrogen leak was caused by the water boiling out of the spent fuel pool in the plant due to the failure of the coolant circulating systems, as the zirconium cladding on the fuel rods reacted to the heat by drawing oxygen from the remaining water, letting off hydrogen. By the way, besides cladding fissionable material in nuke plants, the only other commercial use for zirconium is flashbulbs used in photography. Heat it up to 2000 degrees and it explodes violently. Could have happened but didn’t. Instead, heated zirconium in water filled the plant with hydrogen gas and a spark ignited it. Here’s was the result, taken by an unmanned drone flight (hat tip to iTuliper Don).Radiation levels in the area dropped after the blast and have “now settled at a low level,” Edano said at a briefing in Tokyo today. Asia’s biggest utility “has decided to fill the containment with seawater.”

The reactor at the Fukushima Dai-Ichi plant may remain shut for a year, Seth Grae, chief executive officer of Lightbridge Corp., a nuclear energy consulting firm whose staff previously inspected the Fukushima plant, said March 11 in an interview with Pimm Fox on Bloomberg Television’s “Taking Stock.”

CI: The scene is 100 times worse than the press reports implied.

EJ: Meanwhile, seventy percent of Reactor #1’s fuel rods melted to the bottom of the containment vessel, and more than 30% of #3's. This was later reported in the New York Times briefly – the assertion was deleted from a later version of the story. But it’s the fact, and the information is now in the public domain. At the time, it wasn't. There is evidence that Reactor #1 continues to go critical off and on as they pump ocean water into it and it boils off and they pump more in, as Arnold Gunderson reported. Now they continue to to deal with the buildup of hydrogen gas in the reactor. If it ignites and the vessel blows up, then they’re back to the worst-case scenario that they’ve been trying to avoid since the start. They claim that there’s not enough of a concentration of hydrogen or enough gas space in the primary confinement vessel for it to blow it up, but as nearly everything else that’s been initially reported has turned out to be untrue, I wouldn’t bet my life on it.

Empty VIP lounge at Narita Airport, Tokyo, Japan, March 26, 2011

Source: Eric Janszen

CI: Why didn't TEPCO give the plant the Chernobyl treatment? Bury the reactors in boron and concrete?

EJ: To the best of my understanding, as it was explained to me, that's putting the cart before the horse. Encasing four of the six reactors in boron and concrete is what you do after you’ve failed to achieve containment of fissionable material in the primary reactor vessels and material has escaped into the environment. The fear was that if they stopped the project to cool and contain radioactive material in the reactors and switched over to a project to dump boron and concrete, a process that might take several days at least, there was a good chance that in the interim, while they were conducting that operation, a full meltdown and release of material would occur in one or more of the reactors.

CI: So they averted a Chernobyl?

EJ: The risk in the first few days was for a catastrophe far, far worse than a Chernobyl.

CI: Worse than Chernobyl?

EJ: There are 4,277 metric tons of fuel at the plant, 3,400 tons in seven spent fuel pools plus 877 tons of active fuel in the cores of the reactors. There were only 180 tons of material in total at Chernobyl. Failure to contain the material at Fukushima Daiichi meant the possibility existed for the equivalent of five or eight Chernobyls, rendering a major part of Japan uninhabitable. All of this will all come out in time, just how desperate and high stakes the battle was. Look for a Frontline piece on it some day, maybe. It was a suicide mission for the 50 workers who stayed on during the critical phase of the first week of the crisis. My understanding is that they were told, “If you fail, your country will be destroyed.” Sadly, it is expected that many of those 50, who spent days getting bombarded with gamma radiation and neutrons, may become ill if they aren’t already.

Two dangers faced the reactors for the first week after the crisis and still to some extent face Reactor #1. The first was that the fuel that melted to the bottom of a steel reactor vessel could burn its way through the steel and concrete containments, polluting not only a large area of Japan as in the case of Chernobyl but, due to the fact that the Fukushima Daiichi plants are beside the ocean, also spreading vast quantities of Cesium 137 and other long half-life, water soluble radio isotopes around the world. The other potential risk was that if enough melted fuel accumulated at the bottom of one or more reactor vessels, it could reach critical mass, resulting in a chain reaction, leading to a violent steam explosion and ejection of radioactive materials out of the reactor. They’d have to abandon the site, leading potentially to follow-on meltdowns at one or more of the other five reactors as they over-heated in turn. As long as they were able to keep injecting water into the reactors to keep the fuel sufficiently cooled, these outcomes could be avoided and the risk of a multi-Chernoby scenario would subside over time, and for all but one or possibly two reactors, it has. At the same time, they were struggling to prevent criticality in the spent fuel storage pools. They had to maintain access to the reactors to get boron and water into them. They could not encase them. They had no choice. It was do or die.

Flying over southern Japan, March 26, 2011

Source: Eric Janszen

CI: Fukushima Daiichi is old news this week. They announced it'll take six or nine months to get it cooled down.

EJ: The media cycle rarely coincides with the natural periodicity of the events the media covers. The US media, dependent as it is on advertising revenue, is particularly bad at covering long, drawn out events that occur over many years, such as the dissolution of the global monetary system, a process that's been going on since the early 2000s. The financial media is so disoriented that it covers the possibility of a dollar decommissioning process as if it might or might not begin some time off in the future, when in fact it's been happening for more than a decade, evolving from one stage to another. Complex and nuanced economic, political, and market processes that escalate and de-escalate for years won't receive much coverage after the acute crisis phase ends that draws in an excited and curious audience that causes a spike in ad revenue. In the case of Egypt, for example, the media only got to cover the beginning, the thrilling and promising part of what is likely to be 12 part saga that will involve a pitched battle between the incumbent military junta and the Muslim Brotherhood, with Iran and China backing one side and the US and its allies the other, with the people as usual caught in the middle.

CI: Where is this going?

EJ: The entire region, including the terribly repressive and critically important US military allies in Syria, are being draw into a process of political change that is evolving into proxy wars. My view is that without strong and creative US leadership now, the Arab revolutions are quickly morphing into a new cold war between China and its allies and the US and its allies.

CI: New cold war?

EJ: I call it Cold War II. The US will find China a far more formidable proxy war adversary than the Soviet Union ever was. Totalitarian state finance capitalism combined with mercantilism is infinitely more productive than communism ever was. Throw in China's dollar destroying debt leverage over the US, and you have a prescription for an eventual monetary crisis (see: Economic MAD, 2006). A less well developed form of a the same economic system financed a lunatic racist and militarist Nazi regime so successfully in the 1930s that it was able to challenge the entire rest of the world in productivity and war, and that was only a few years after the German economy was ruined by war and hyperinflation, followed by the sudden withdraw of US and British foreign direct investment in 1930 that crashed the Germany economy anew. The rise of the right in Finland and across Europe today is being accelerated by divisions of an escalating sovereign debt crisis.

CI: You are a proponent of nuclear power. You push it in your book The Postcatastrophe Economy: Rebuilding America and Avoiding the Next Bubble

.

.EJ: I do. I’m in favor of safe, next generation nuclear power plants, based on pebble bed nuclear plant designs, and in the interim before they are available, small light water reactors that are well dispersed, not several large reactors and concentrated in one plant.

CI: Pebble bed nukes?

EJ: There are no control systems to control the nuclear reaction in pebble bed designs. There are no control systems to fail. The fission reaction cannot go critical. Many of these old plants are insane.

CI: Insane?

EJ: Put 200 metric tons of highly poisonous radioactive material in a giant steel and concrete jar and control the nuclear reaction with control rods and cooling systems. If the controls and cooling systems fail and the material escapes, a huge area around the plant will be rendered uninhabitable for a century. Now keep several hundred tons of spent fuel on the premises, also vulnerable to an uncontrolled reaction. Now put six such reactors all at the same location. Now put them in a highly seismically unstable area next to the ocean that is famously vulnerable to severe tsunamis. Does that sound sane to you?

CI: How do insane decisions to build things like this get made?

EJ: That’s the key question, isn't it? The same way that a monetary system like ours gets built, because a powerful interest group decides it's a good idea at the time, and effectively sells the idea to everyone else, including the future victims of the failure of the system. After our monetary system finishes melting down, everyone will wonder how it was allowed to develop in the first place, and the architects of the system will ask, Who could have known?

The Fukushima Daiichi plant disaster ties into the iTulip theme since 1998: How do groups of highly educated and capable people collectively make crazy decisions, like building a nuclear power facility in an earthquake zone or a monetary system that can only grow more and more unstable over time?

CI: Do you think the earthquake in Japan will boost the Japanese economy by providing jobs for re-construction?

EJ: That's the Broken Window Fallacy. The question was settled 150 years ago, yet it still comes up in the media every time there's a disaster as if it were a valid topic of debate. How about we reopen the debate over whether the earth is the center of the universe?

CI: No re-construction boom?

EJ: They will repair the roads but natural catastrophes do not improve economies. By that logic, New Orleans should be booming after Katrina. Look at before and after pictures of Indonesia since the tsunami five years ago. Most of the area that was destroyed remains undeveloped. An enterprising friend of mine flew there six months later to shop for property bargains. He bought a bunch of land. Thing is, no one wants to build on property where a major natural disaster occurred within recent memory. Who wants to live where so many people died? The place is filled with ghosts. Who will insure it? In Japan’s case, the wrecked areas may not be rebuilt for a generation.

CI: Broken window fallacy?

EJ: The name comes from Frédéric Bastiat’s parable of the broken window from Ce qu'on voit et ce qu'on ne voit pas (1850):

Have you ever witnessed the anger of the good shopkeeper, James Goodfellow, when his careless son happened to break a pane of glass? If you have been present at such a scene, you will most assuredly bear witness to the fact that every one of the spectators, were there even thirty of them, by common consent apparently, offered the unfortunate owner this invariable consolation—"It is an ill wind that blows nobody good. Everybody must live, and what would become of the glaziers if panes of glass were never broken?"

Now, this form of condolence contains an entire theory, which it will be well to show up in this simple case, seeing that it is precisely the same as that which, unhappily, regulates the greater part of our economical institutions.

Suppose it cost six francs to repair the damage, and you say that the accident brings six francs to the glazier's trade—that it encourages that trade to the amount of six francs—I grant it; I have not a word to say against it; you reason justly. The glazier comes, performs his task, receives his six francs, rubs his hands, and, in his heart, blesses the careless child. All this is that which is seen.

But if, on the other hand, you come to the conclusion, as is too often the case, that it is a good thing to break windows, that it causes money to circulate, and that the encouragement of industry in general will be the result of it, you will oblige me to call out, "Stop there! Your theory is confined to that which is seen; it takes no account of that which is not seen."

It is not seen that as our shopkeeper has spent six francs upon one thing, he cannot spend them upon another. It is not seen that if he had not had a window to replace, he would, perhaps, have replaced his old shoes, or added another book to his library. In short, he would have employed his six francs in some way, which this accident has prevented.

Now, this form of condolence contains an entire theory, which it will be well to show up in this simple case, seeing that it is precisely the same as that which, unhappily, regulates the greater part of our economical institutions.

Suppose it cost six francs to repair the damage, and you say that the accident brings six francs to the glazier's trade—that it encourages that trade to the amount of six francs—I grant it; I have not a word to say against it; you reason justly. The glazier comes, performs his task, receives his six francs, rubs his hands, and, in his heart, blesses the careless child. All this is that which is seen.

But if, on the other hand, you come to the conclusion, as is too often the case, that it is a good thing to break windows, that it causes money to circulate, and that the encouragement of industry in general will be the result of it, you will oblige me to call out, "Stop there! Your theory is confined to that which is seen; it takes no account of that which is not seen."

It is not seen that as our shopkeeper has spent six francs upon one thing, he cannot spend them upon another. It is not seen that if he had not had a window to replace, he would, perhaps, have replaced his old shoes, or added another book to his library. In short, he would have employed his six francs in some way, which this accident has prevented.

EJ: Assume the laws of human nature are in force and you are not getting the truth when a powerful and politically connected industry is in crisis. It took decades for the health risks of tobacco to come to light. The media was no help until the tobacco industry was already on the ropes. Once cigarette advertising was widely banned and the advertising revenue dried up, it was safe for the media to cover the obvious dangers of a product that killed millions. Only then did the media join in on the side of consumers. We re-opened iTulip in March 2006 to warn about the risks to the financial system and the rest of us posed by credit risk pollution. We specifically identified credit derivatives, asset-backed securities, secondary-market syndicated loans, interest-only mortgages, and sub-prime mortgages and consumer loans as the future nexus of the coming credit crisis, a crisis didn’t occur for another two years. Two years is about my average forward vision on these events. As the global monetary system finishes melting down, don't expect a valid real-time explanation of events from the media. On the other hand, don't assume that the crisis will necessarily "go Chernoby." There will be a lot of noise and very little signal. For those of us who started to prepare for this ten years ago, it's all about the exit.

CI: Today you’re warning about a monetary system crisis and oil energy crisis two to three years out, with inflation running to double-digits?

EJ: I want readers to get into the habit of referring to an inflation process instead of inflation. You’ve heard me say it 100 times, but it’s very important to get your head around the fact that the results of an inflation process at any given time have to be distinguished from the underlying forces that are producing the results at any time. Otherwise all manner of errors of deduction occur.

CI: What kind of errors?

EJ: One mistake is that all inflation processes are the same in all places and times. The most persistent mistake is the idea that high all-goods price inflation is inconsistent with high unemployment all or even most of the time. No amount of evidence can dislodge this misconception. Americans in the US find the idea intuitive from personal experience, but that’s not scientific.

CI: Count me with them. High unemployment and inflation don’t make sense to me.

EJ: The mistake comes from the intuitive idea that if there are many unemployed, who’s got money to buy stuff? High unemployment means labor has no pricing power. Goods and services prices have to fall along with wages. As demand falls prices fall. All things being equal, this intuitive idea roughly conforms to fact, at least for a while. But all things are not always equal in the real world for long. Inflation is, simultaneously, a factor of the demand for the money that is used in transactions relative to the quantity of that money, and the supply of the goods and services being purchased with that money. The demand for money is a related to but independently operating factor of inflation. Remember our forecast in 2007 that the Fed was to meet the surging demand for money that occurs during a private credit market crisis, to halt deflation? Remember that I forecast that dollar depreciation, the Foolproof Way of ending deflation was the unstated policy tool? Now the challenge is to respond to reverse the process, to prevent a sudden collapse in the demand for money. You can see the collapse happening now in gold and silver prices as the demand for money falls and consumers move out of paper assets and into hard assets. The Fed thinks it can stop this by raising interest rates, to get money back out of hard assets and into paper. But raising interest rates today will do the opposite, because the economy will contract and that will weaken the dollar further. It's not stagflation, it's the Ka-Poom debt and currency crisis process that I laid out 10 years ago.

CI: Show me an example of unemployment and inflation rising together.

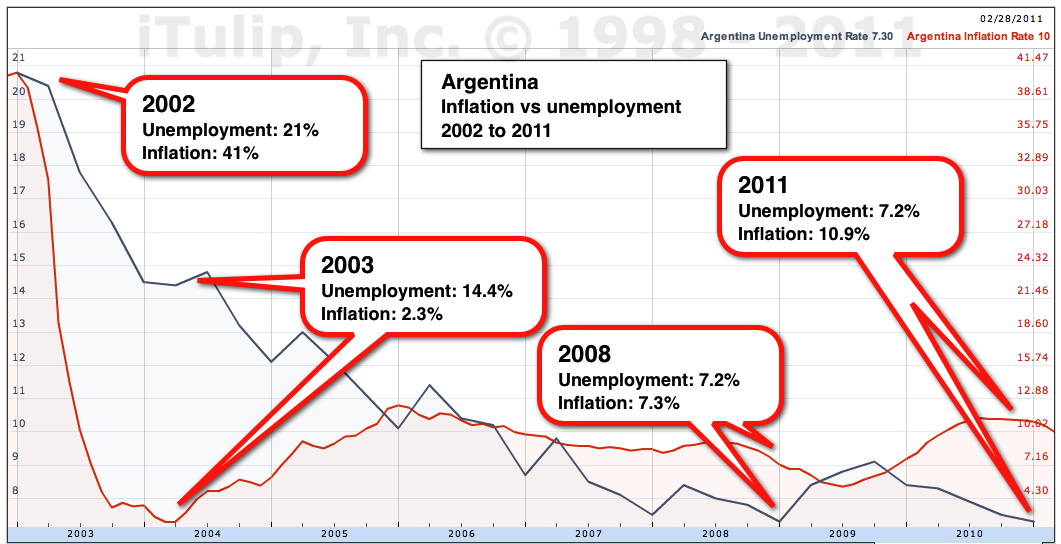

EJ: Consider the comparison of unemployment and inflation in Argentina starting in 2002, immediately after the latest Argentina Ka-Poom. The currency and bond crisis peaks in 2002. Unemployment stands at 21% and inflation at 41%. One year unemployment was 14% and inflation was minus 1.5% – a brief period of deflation. Both unemployment and inflation exploded together from this base of low inflation and high unemployment.

CI: What happened to cause high unemployment and inflation?

EJ: Argentina’s currency peg collapsed, producing a wave of inflation as businesses failed both due to the inflation and the collapse of the credit markets.

CI: A classic iTulip Ka-Poom scenario from 1999?

EJ: Yes, as a mechanism but the US bond market and dollar cannot go down in precisely the same way. The US is not Argentina. We will see a different form of the process but with many of the same elements. We'll talk about that later when we get to the topic of gold. Getting back to Argentina and our discussion of inflation versus unemployment, starting from that peak in inflation and unemployment in 2002, as the bond and currency markets recovered in 2003 and 2004, inflation fell back to 2.3%, where the US inflation rate is purportedly today, while unemployment fell to 14.4%.

If you took a snapshot of that single 2003 to 2004 period you might ask, Why is inflation falling if unemployment is falling? Ff you look at how those high rates of inflation and unemployment came about, you’d see that inflation fell a lot more than unemployment; unemployment fell by 30% as inflation fell by 94% after the bond and currency crisis because of changes in the demand for money as interest rates fell at the same time labor markets recovered.

Then in 2005 inflation rises to nearly 11% as unemployment falls to 10%. During this period we finally see the correlation of falling unemployment and rising inflation that we’d expect to see, the relationship that we can relate to from experience and which is intuitive to most Americans; labor markets recovery while the demand for and supply of money is stable.

This is followed by period of falling inflation and rising unemployment starting in early 2008 until mid 2009, during the global financial crisis. Unemployment rises to 9.1%, then falls to 7.3% where it is today, when inflation is around 11%. Note that the previous time unemployment was 7.3%, inflation was only 7.2% not 11% as it is today.

Times Square NYC January 2011 versus Taipei April 2011

Photo Credit: Eric Janszen

CI: How do we relate this to the US if the US is nothing like Argentina?

EJ: Argentina is a small, politically insignificant economy. It owed its foreign debt in US dollars. The US doesn't fit the model. My theory since 2007 for the US is that when the goods and services supply constrained postcatastrophe economy is reflated via monetary and fiscal stimulus, that unemployment will recover, demand for goods and services will rise, demand for money will fall relative to the massive supply that was created to halt the deflation of late 2008 and early 2009, while the weak dollar will continue to exert cost-push inflationary pressures. Oil prices will surge over $100 in a new Peak Cheap Oil Cycle. Inflation will rise off a much higher level of unemployment than in previous recoveries due to these factors. That’s the special character of this inflation process, unlike the 1970s in the US or anywhere else.

CI: Inflation without wage inflation?

EJ: Unintuitive, but wage inflation is not yet relevant at this stage of our inflation process. Government wage rates usually lead wage inflation.

CI: How?

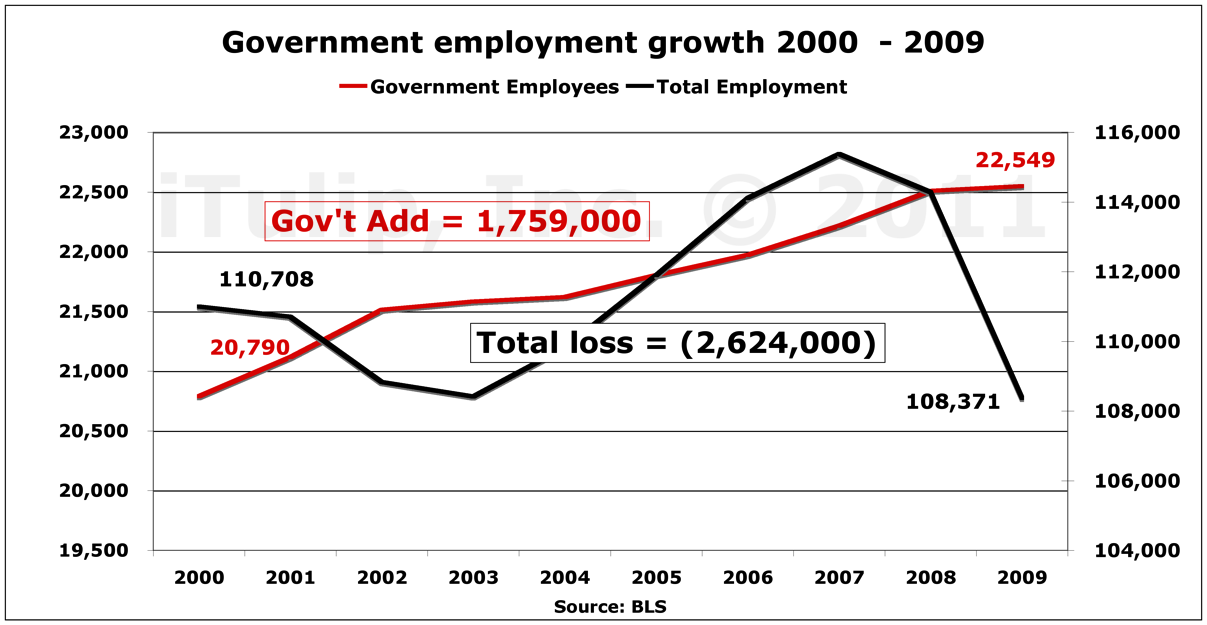

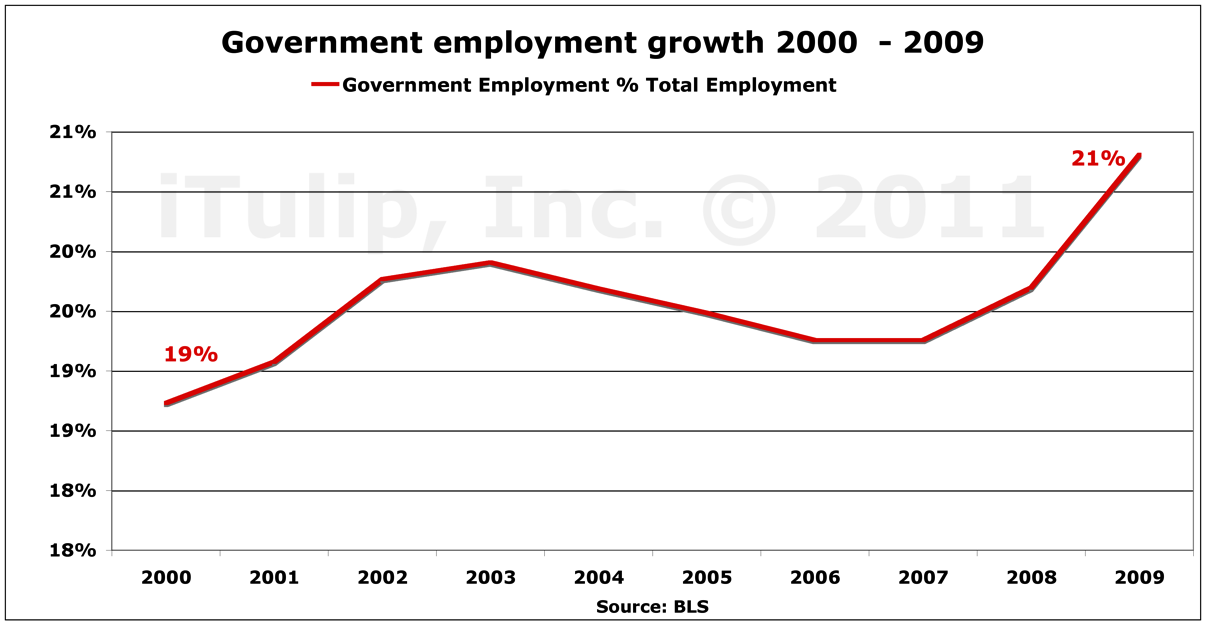

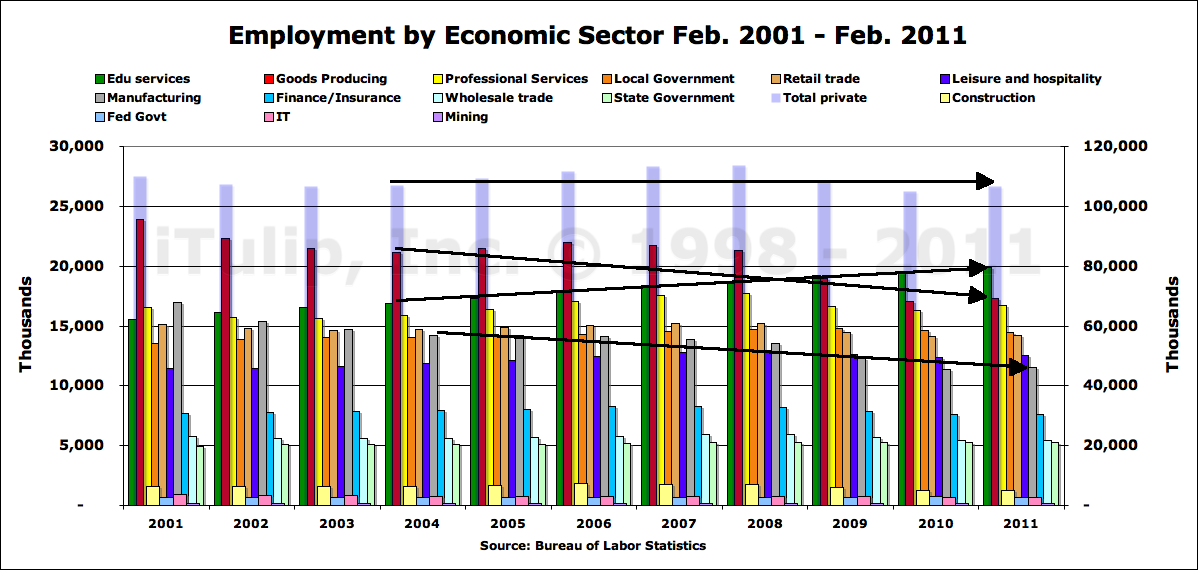

EJ: What matters is how the structure of the US economy was changed by the two bubbles and reflations over the past ten years, as private and public debt levels ratcheted up. Consider the fact that total employment fell by 2.6 million jobs since the year 2000 while local, state, and federal government employment grew by 1.8 million.

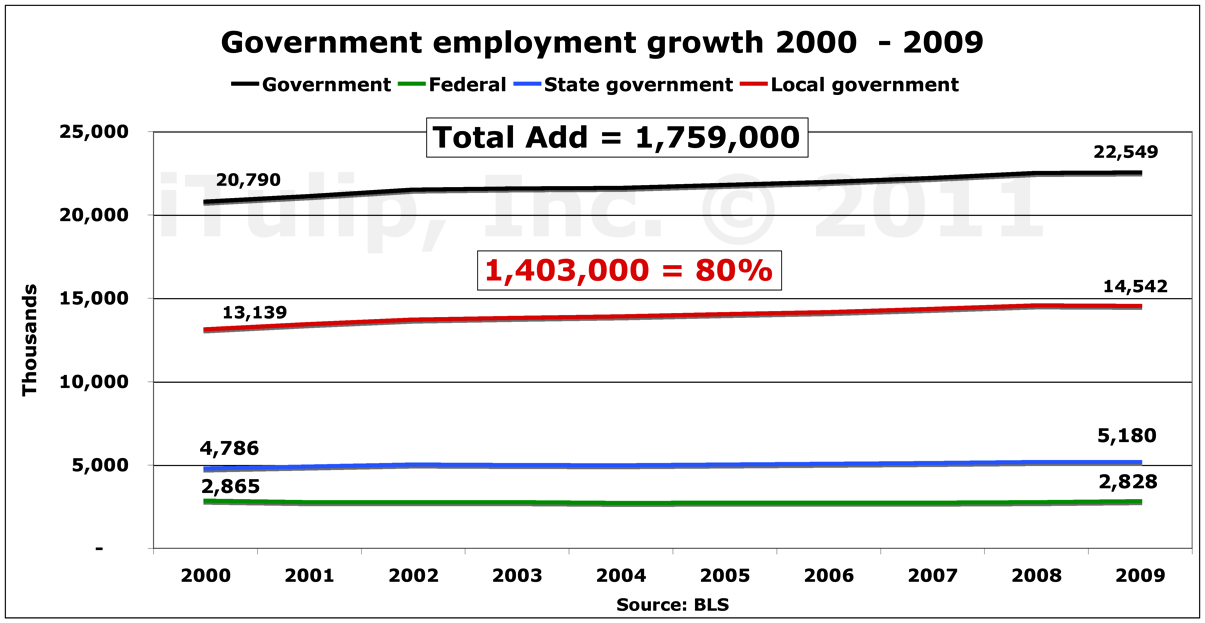

Take a closer look and you find that 80% of the employment growth within the government sector was in local government payrolls.

Two out of every 10 people in the US work for the government.

CI: So we are like Argentina.

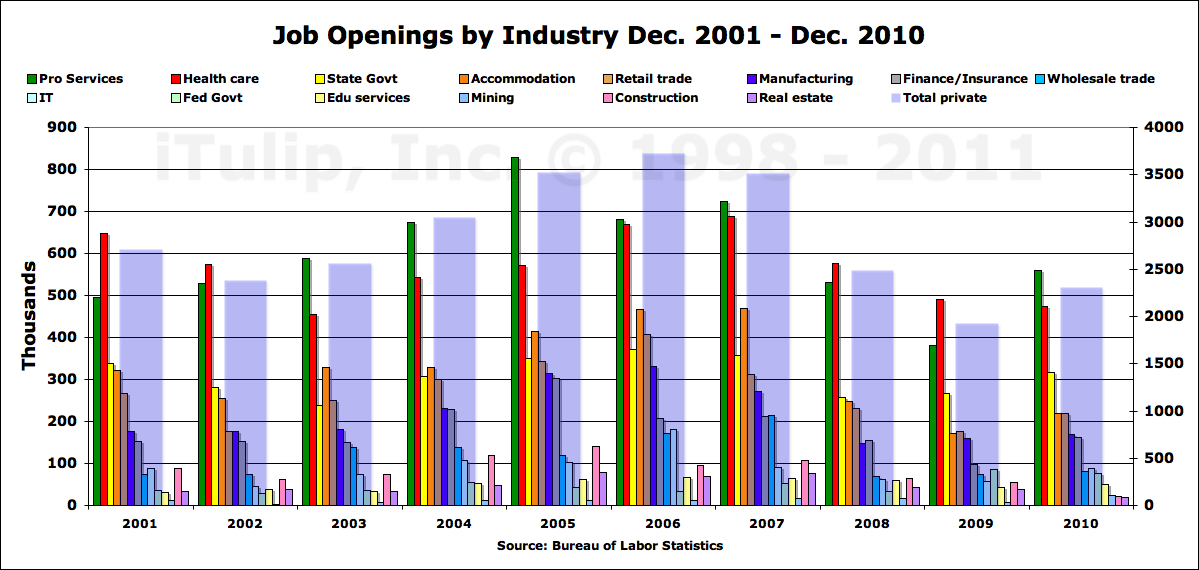

EJ: You can say we are headed in that direction. There are only as many jobs today in the private sector as there were in 2004, seven years ago. The goods producing and manufacturing sector employment actually shrank since 2004. Only the educational services and local government sectors showed any appreciable rise to compensate for the employment losses in the goods producing and manufacturing sectors, to keep the total level flat. In 2001, 14 million were employed in local government and 17 million in manufacturing. Ten years later, 15 million are employed in local government and 12 million in manufacturing.

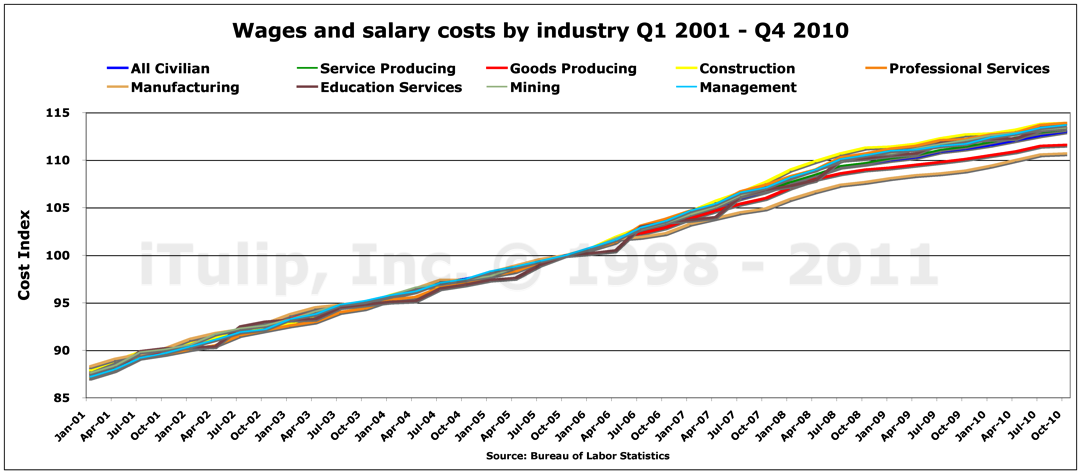

CI: Is wage price inflation weakest in the sectors where employment has declined?

EJ: That's what you'd expect and it is so.

You can see above that the wage cost index for the goods producing and manufacturing sectors has been slower than for those that have remained flat. You can see wage costs rising at a slower rate overall since the end of 2007.

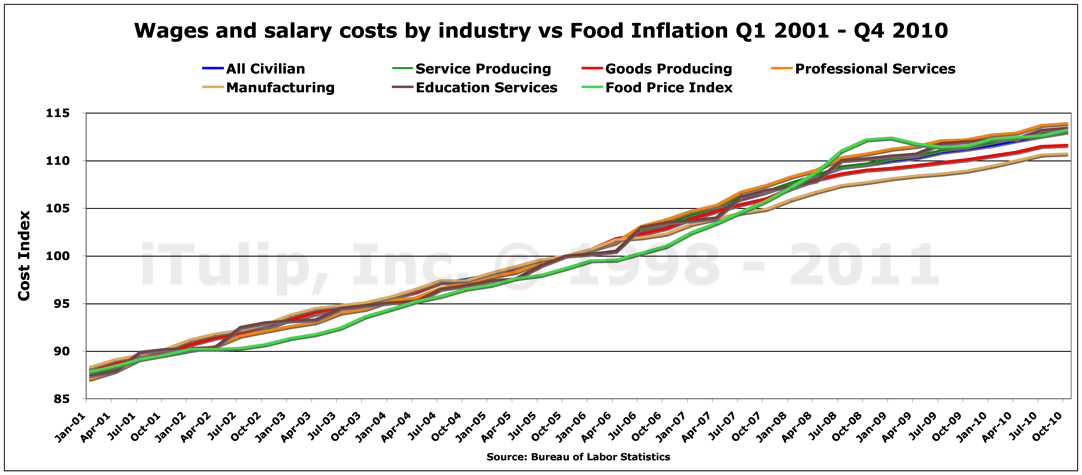

CI: What if you compare wage cost indexes with food price indexes?

EJ: What's interesting is that food price inflation went up rapidly in 2008, dropped in 2009, and now parallels wage costs. Before the financial crisis and reflation via dollar depreciation, wage costs increased faster than food prices. Food felt cheap. Now it doesn't, and it feels expensive if you work in the goods producing and manufacturing sectors that are shrinking and wage costs are rising more slowly than than the food price index.

CI: I can't tell from these charts if the labor market is really improving.

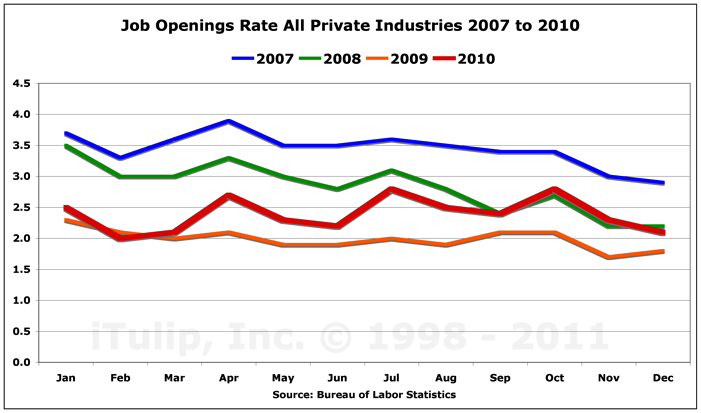

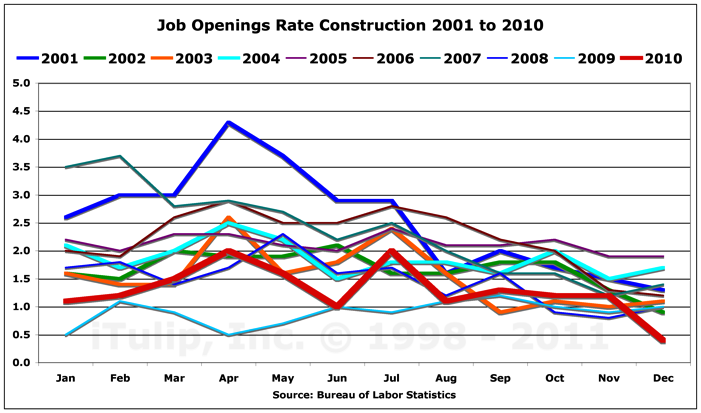

EJ: Right, the way to do that is to look at the job openings rate. At just above 2%, they are not much better than they were during the dark days of 2009. The job openings rate tends to peak in April and decline through the rest of the year. Below we compare the rate for the last four years starting in 2007.

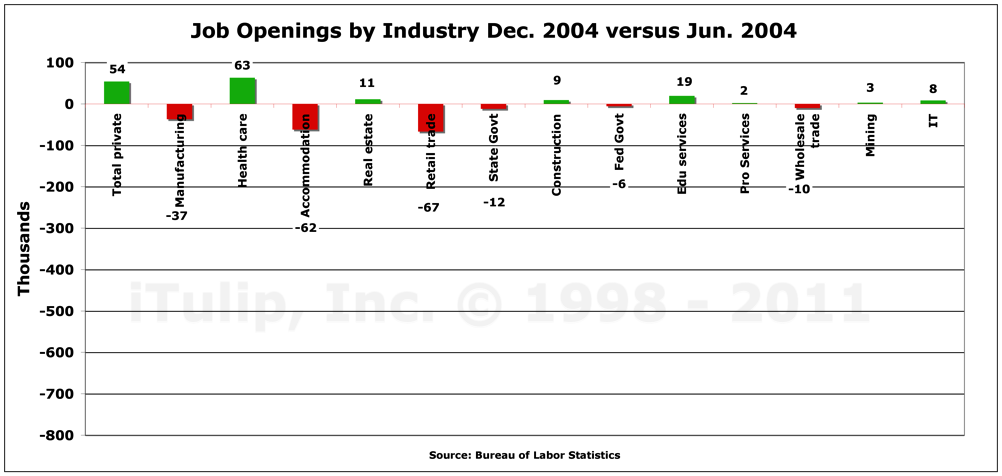

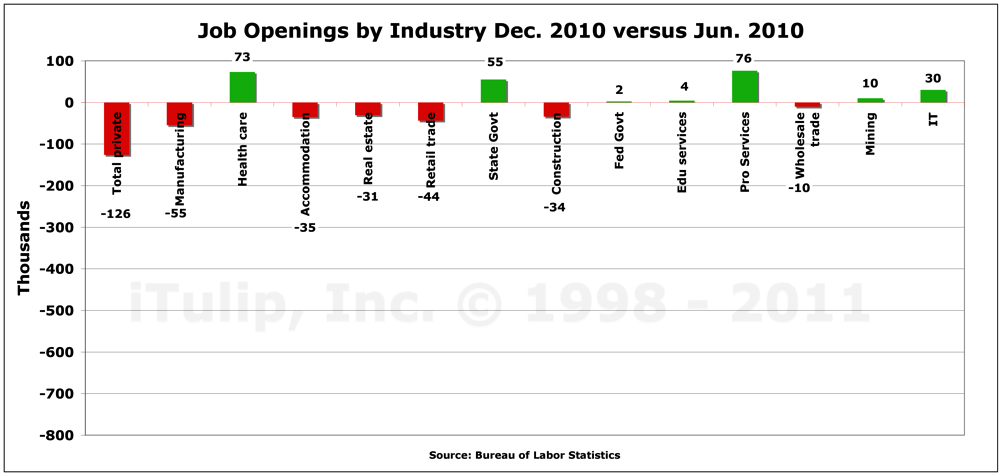

To get an idea of how the jobs recovery today compares to past recoveries, such as the housing bubble boom recovery starting in 2004, the change in the number of job openings from the middle to the end of the year is instructive.

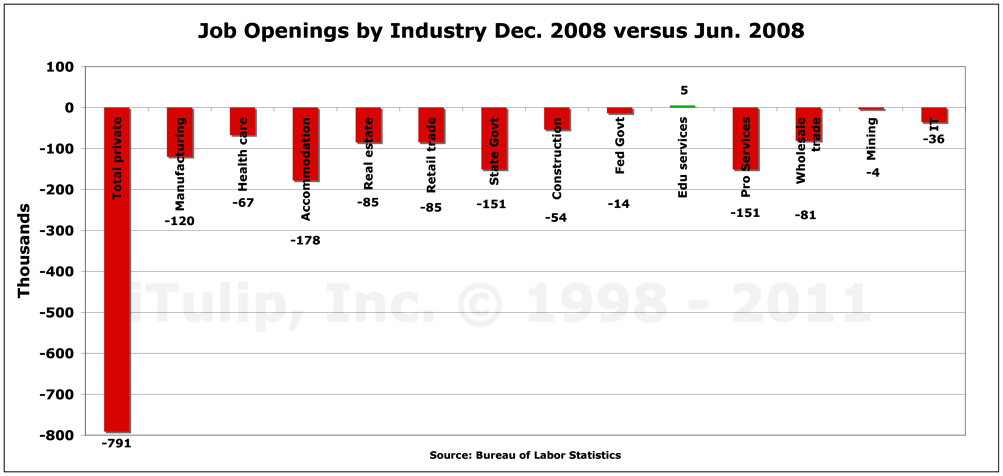

During the darkest days of the past recession, job openings collapsed over the June to December period. Only educational services increased job openings -- by 5,000 jobs across the entire US economy.

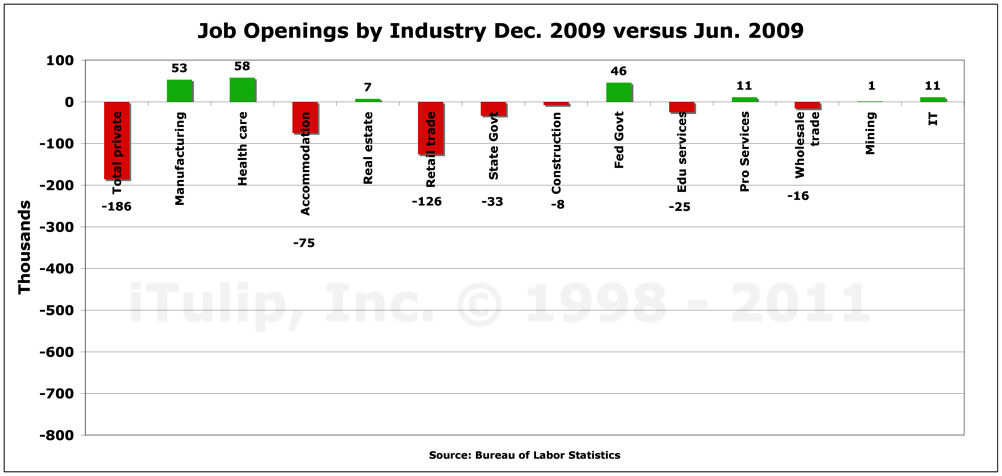

The picture, while still bad in 2009, improved vastly and job openings shrank by only 186,000 versus 791,000 the year before. After a year like 2008, any improvement in the job openings picture feels like a recovery.

But even in 2010, a supposedly strong recovery year when the stock markets packed on trillions in market cap, the period was net negative for private sector job openings growth. Job openings declined by 126,000. Compare that to 2004 above when the economy added 54,000 job openings.

CI: Where are the jobs?

EJ: Overall, the total number of job openings is almost back up to where it was at the worst part of the last recession in 2002, which is to say, terrible. Job openings are rising fastest in the largest employment sector, professional services, flat in the second largest, health care, and rising in state and local government.

CI: Do you have a best and worst chart on job openings, by sector I mean?

EJ: The worst sector is of course construction, but it doesn't employ many workers, as you can see from the Employment by Economic Sector chart above. For construction, the job openings rate peaked at nearly 4.5% in April 2001 and hit an all time low of 0.5% in December last year. If you're in construction, your industry is basically dead in the water.

CI: The picture of the economy that you are painting is one where government and professional services employment cost increases fuel an inflation spiral for everyone else. Won't weak labor markets in the other sectors cancel out the effects of wage inflation in the government and professional services sectors?

EJ: It doesn't work that way. Depends on all the other factors that are coming into play, including demand for money, which is determined by incomes and interest rates. If inflation expectations are rising, and a perception that wage rates are rising at least in some industries, and interest rates are not rising, demand for money declines, and inflation expectations are met with rising prices. In this way, commodity price inflation is transmitted into the entire pricing complex. Over the next year and a half, rising wage rates in growing industry sectors will fuel a new stage of the inflation process starting in the second half of the year.

Global Monetary Meltdown - Part II: The first inflation, but not the last ($ubscription)

The reflated postcatastrophe economy has morphed into an inflationary boom economy. In many ways it feels like a recovery, with retails sales and other measures rising just as they would after a recession under normal conditions. This is responsible for the resilience of the stock market. Two things are happening: demand for money is falling and demand for goods and services is rising.

• Inflation expectations at the gas pump

• Surviving suppliers pass on commodity price inflation to consumers employed in the professional services industry and state government

• Purchasing power on the wane

• Global consumer price inflation breaches 5%

• FIRE Economy goes global

• US debt levels take the cake

• Real DJIA revisited

• Housing bubble collapse revisited

• Peak Cheap Oil Cycle revisited

• What price gold when the gold window is re-opened?

Spring crocuses bloom with the global inflationary boom, April 2011

Photo Credit: Eric Janszen

CI: What season of the inflation process are we in today?

EJ: We are in the spring of an inflationary boom, when a persistently weak dollar and accommodative monetary policy continue to increase inflation expectations in a time of high but declining unemployment. The reflated postcatastrophe economy has morphed into an inflationary boom economy. In many ways it feels like a recovery, with retail sales and other measures rising just as they would after a recession under normal conditions. This is responsible for the resilience of the stock market, and we'll get the the stock market shortly. Two things are happening: demand for money is falling and demand for goods and services is rising.

CI: I’ve never understood this idea of inflation expectations. How is it measured?

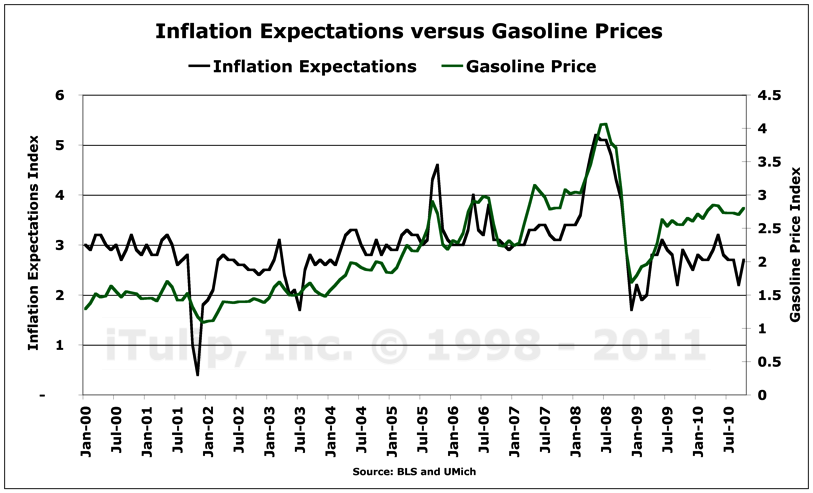

EJ: There are several measures of inflation expectations. This article at the Cleavland Fed does a decent job of explaining them. The most well known and widely used is the University of Michigan Survey of Consumer Attitudes and Behavior. For all of the statistical science that goes into it, it's my contention that what they are really measuring is gasoline prices. In other words, the average consumer's expectations of future inflation are set at the gas pump.

iTulip Select: The Investment Thesis for the Next Cycle™

__________________________________________________

For a concise, readable summary of iTulip concepts read Eric Janszen's 2010 book The Postcatastrophe Economy: Rebuilding America and Avoiding the Next Bubble

.

.To receive the iTulip Newsletter/Alerts, Join our FREE Email Mailing List

To join iTulip forum community FREE, click here for how to register.

Copyright © iTulip, Inc. 1998 - 2011 All Rights Reserved

All information provided "as is" for informational purposes only, not intended for trading purposes or advice. Nothing appearing on this website should be considered a recommendation to buy or to sell any security or related financial instrument. iTulip, Inc. is not liable for any informational errors, incompleteness, or delays, or for any actions taken in reliance on information contained herein. Full Disclaimer

Comment