|

Recent bond yield increases didn't only surprise the markets. They surprised the Fed, too. Why? What are these guys smoking?

Remember Greenspan's famous "Conundrum" speech? In semiannual testimony of the Monetary Policy Report to the Congress before the Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, U.S. Senate, February 16, 2005, he said:

There is little doubt that, with the breakup of the Soviet Union and the integration of China and India into the global trading market, more of the world's productive capacity is being tapped to satisfy global demands for goods and services. Concurrently, greater integration of financial markets has meant that a larger share of the world's pool of savings is being deployed in cross-border financing of investment. The favorable inflation performance across a broad range of countries resulting from enlarged global goods, services and financial capacity has doubtless contributed to expectations of lower inflation in the years ahead and lower inflation risk premiums. But none of this is new and hence it is difficult to attribute the long-term interest rate declines of the last nine months to glacially increasing globalization. For the moment, the broadly unanticipated behavior of world bond markets remains a conundrum. Bond price movements may be a short-term aberration, but it will be some time before we are able to better judge the forces underlying recent experience.

Not so short term, as it turned out. September 14, 2006, The Economist explained in Unnatural causes of debtAnalysts have put forward two main explanations for the low level of real bond yields in recent years. The first is that high saving (in relation to investment) by Asian economies and Middle East oil exporters has caused a global saving glut, pushing down yields. These economies are running large current-account surpluses, and much of that money has been piled up in official reserves, particularly in American Treasury securities, as central banks have intervened in the foreign-exchange market to prevent their currencies from rising.

Of gluts and floods

Various estimates suggest that such foreign-exchange intervention reduced American yields by less than one percentage point in 2004-05. But Nouriel Roubini and Brad Setser of Roubini Global Economics reckon that the impact could be larger. Most studies ignore the fact that without official intervention by foreign central banks the dollar would be lower and hence American inflation higher, which would push bond yields higher. And if central banks were not buying dollars to prop up the currency, many private investors might hold fewer greenbacks, which again would push up yields. Adding up these and other factors, Messrs Roubini and Setser reckon that American Treasury bond yields would have been two percentage points higher in recent years if central banks in emerging economies had not bought dollar reserve assets.

A second explanation for low bond yields is that excess liquidity has pushed up the prices of all assets, including bonds. Over the past few years, the global money supply has grown at its fastest pace since the 1980s. This excess liquidity has not pushed up conventional inflation (thanks largely to cheap Chinese goods), but has fed into a series of asset-price bubbles around the world.

Both developed and emerging economies have contributed to this flood of liquidity. Central banks in rich countries have held interest rates abnormally low to offset disinflationary pressures from emerging economies. At the same time, to prevent their currencies rising, emerging economies have also held interest rates low and engaged in heavy foreign-exchange intervention, which has inflated their money supplies.

Both of these explanations for low interest rates—the saving glut and the excess liquidity—involve emerging economies; either through their impact on developed economies' inflation and hence monetary policy, or through their foreign-exchange intervention. In that sense, global monetary conditions are increasingly being influenced by policies in Beijing as much as in Washington, DC. Over the past year, emerging economies have accounted for four-fifths of the growth in the world's monetary base.

We have since April 2006 posited that China is in a better position to do without the U.S. as a source of export demand than the U.S. is in a position to do without China as a source of demand for dollar denominated financial assets. Of gluts and floods

Various estimates suggest that such foreign-exchange intervention reduced American yields by less than one percentage point in 2004-05. But Nouriel Roubini and Brad Setser of Roubini Global Economics reckon that the impact could be larger. Most studies ignore the fact that without official intervention by foreign central banks the dollar would be lower and hence American inflation higher, which would push bond yields higher. And if central banks were not buying dollars to prop up the currency, many private investors might hold fewer greenbacks, which again would push up yields. Adding up these and other factors, Messrs Roubini and Setser reckon that American Treasury bond yields would have been two percentage points higher in recent years if central banks in emerging economies had not bought dollar reserve assets.

A second explanation for low bond yields is that excess liquidity has pushed up the prices of all assets, including bonds. Over the past few years, the global money supply has grown at its fastest pace since the 1980s. This excess liquidity has not pushed up conventional inflation (thanks largely to cheap Chinese goods), but has fed into a series of asset-price bubbles around the world.

Both developed and emerging economies have contributed to this flood of liquidity. Central banks in rich countries have held interest rates abnormally low to offset disinflationary pressures from emerging economies. At the same time, to prevent their currencies rising, emerging economies have also held interest rates low and engaged in heavy foreign-exchange intervention, which has inflated their money supplies.

Both of these explanations for low interest rates—the saving glut and the excess liquidity—involve emerging economies; either through their impact on developed economies' inflation and hence monetary policy, or through their foreign-exchange intervention. In that sense, global monetary conditions are increasingly being influenced by policies in Beijing as much as in Washington, DC. Over the past year, emerging economies have accounted for four-fifths of the growth in the world's monetary base.

In Economic M.A.D. we said:

Easy to confuse the commitment of one nation to another for an act of friendship. As mid-19th century British Prime Minister Lord Palmerston once commented, nations don’t have friends; nations have interests. The mutual interests of China and the U.S. are the kind that kept the U.S. and the Soviet Union from going at each other with nukes during the Cold War.

China and the U.S. are running inter-dependent bubble economies, relying on the economic equivalent of Mutually Assured Destruction (M.A.D.) to keep one from blowing up the other’s economy. Whether by intent or accident, sooner or later market forces will assert themselves and both economies will go through tough transitions. How will the world look after that?

Our expectation was that in time the U.S. would experience a housing bubble bust driven recession about two years after the start of a ten year decline in housing prices, which began mind-2005. Well before consumption of Chinese exports actually declined, China would step up exports to other Asian and European markets. Then, likely a few months before the recession, China would begin to reduce purchases of U.S. financial assets, especially treasuries. The long term result of the unwinding of the conundrum is a persistent U.S. stagflation.China and the U.S. are running inter-dependent bubble economies, relying on the economic equivalent of Mutually Assured Destruction (M.A.D.) to keep one from blowing up the other’s economy. Whether by intent or accident, sooner or later market forces will assert themselves and both economies will go through tough transitions. How will the world look after that?

iTulip's John Serrapere spells it out in detail in his series Stagflation Trade.

Last week, the leading edge of the recession arrived in the form of a rapid rise in bond yields. This came as a surprise to the Fed, apparently. The followed was extracted from the June 2007 Livingston Survey (PDF).

What is The Livingston Survey?

The Livingston Survey was started in 1946 by the late columnist Joseph Livingston. It is the oldest continuous survey of economists' expectations. It summarizes the forecasts of economists from industry, government, banking, and academia. The Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia took responsibility for the survey in 1990.

The Livingston Survey's data base offers the actual releases, documentation, mean and median data of all the respondents as well as the individual responses from each economist. The individual responses, which are kept confidential by using identification numbers, are in a separate file, organized by variable.

Here's what the recent June 2007 report projected.The Livingston Survey's data base offers the actual releases, documentation, mean and median data of all the respondents as well as the individual responses from each economist. The individual responses, which are kept confidential by using identification numbers, are in a separate file, organized by variable.

Interest Rates Will Increase Slightly in the Near Term

Interest rates on three-month Treasury bills will essentially remain steady over the next year and a half, rising slightly by the end of 2008, according to the forecasters. They expect the interest rate to be 4.90 percent in June 2007, 4.93 percent in December 2007, and 4.92 percent in June 2008. They predict the rate will increase to 4.95 percent by December 2008. Long-term interest rates are expected to rise over the next year and a half. The interest rate on 10-year Treasury bonds is projected to be 4.78 percent by the end of June 2007 and then to rise to 4.95 percent by December 2007. In 2008, a more gradual increase is expected: the forecasters predict that the rate will be 5.00 percent by June 2008 and that it will inch up to 5.05 percent by December 2008. The current forecasts are slightly lower, on average, than the December 2006 forecasts.

As readers know, 10-year Treasury bonds are already above 5.20. Doesn't exactly inspire confidence, does it? The folks over at Lombard Street Research seem to have a better handle on the situation.Interest rates on three-month Treasury bills will essentially remain steady over the next year and a half, rising slightly by the end of 2008, according to the forecasters. They expect the interest rate to be 4.90 percent in June 2007, 4.93 percent in December 2007, and 4.92 percent in June 2008. They predict the rate will increase to 4.95 percent by December 2008. Long-term interest rates are expected to rise over the next year and a half. The interest rate on 10-year Treasury bonds is projected to be 4.78 percent by the end of June 2007 and then to rise to 4.95 percent by December 2007. In 2008, a more gradual increase is expected: the forecasters predict that the rate will be 5.00 percent by June 2008 and that it will inch up to 5.05 percent by December 2008. The current forecasts are slightly lower, on average, than the December 2006 forecasts.

China breaks up with the US

The Sino-US marriage of convenience is breaking up as the US households’ willingness to borrow and spend gets exhausted. Falling US real imports reveal weak domestic demand. Asian exports to the US are faltering. Chinese exports to the US are holding up, but not for long. China’s new object of desire – thriving Europe – adds an acrimonious twist by allowing the yuan/dollar rate to rise. Last week’s US bond market sell-off was the result, likely to further depress the economy.

China and the US have enjoyed a long marriage of convenience. Actually, China moved in uninvited. But as it put its huge savings on the table, America found it too rude to refuse. Both economies have enjoyed the good times as China’s excess savings found an outlet to induce the extra US spending the Communist state needed to keep its economy growing fast. The world as a whole enjoyed Goldilocks: low interest rates, low inflation, rising asset prices and a booming economy. As long as liquidity was sloshing around, providing the collateral for the build-up of domestic debt, the US consumer could enjoy spending beyond their means. But overinvestment in the housing market has put a spanner in the works. House prices are no longer rising; household assets are no longer rising; the borrowing and spending spree is over.

US April trade data, out last Friday, showed real non-oil goods imports down in April on the first quarter, suggesting consumer spending is faltering. Strong survey data may have prompted analysts to expect a rebound, but the real data are pointing to continued weakness. The US import downswing has been reflected in falling Asian exports. Exports to the US from Malaysia, Thailand and Singapore have all been declining since the end of last year. Today’s May trade data from China shows that exports to the US have held up well, growing by 16% in the year, although down from the 21% in Q1.

So far in the second quarter Chinese total exports have expanded at a fast pace. At 27%, although down from 29% in Q2, annual growth remains strong. China’s current account surplus continues to swell, with no respite in sight. The revival of Euroland, de-coupling from the US for the time being, has helped Chinese exports forge ahead. It has also allowed the Chinese to let the yuan appreciate vis-à-vis the dollar. No wonder that the US bond market sold off last week as it is no longer the default investment destination for China, or the rest of Asia for that matter. China’s new object of desire has turned its breakup with the US into an even more acrimonious one. Higher bond yields are not what the US needs now, even though some in the Fed might think so. The US has a stagflation problem, not an inflation one.

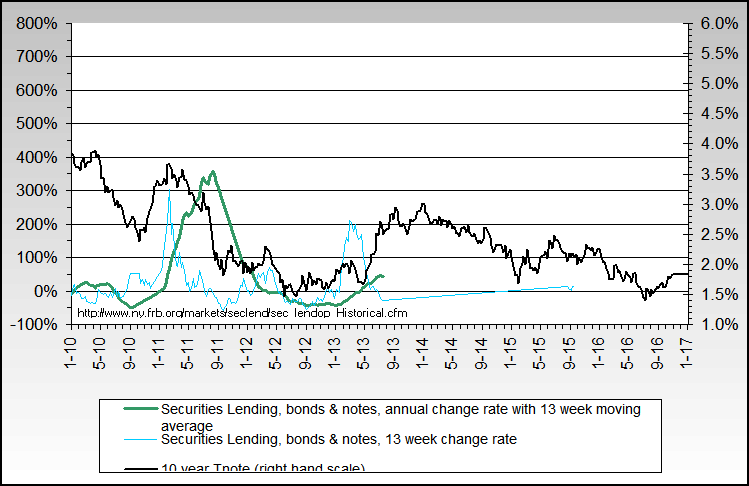

Greenspan's "conundrum" is running in reverse. If the dynamic of the conundrum was to hold interest rates lower than otherwise expected during a period of strong economic growth in the U.S., no one should be surprised that as the process reverses the U.S. is due to experience high interest rates during a period of low growth and recession as foreign demand for US treasuries declines. The Sino-US marriage of convenience is breaking up as the US households’ willingness to borrow and spend gets exhausted. Falling US real imports reveal weak domestic demand. Asian exports to the US are faltering. Chinese exports to the US are holding up, but not for long. China’s new object of desire – thriving Europe – adds an acrimonious twist by allowing the yuan/dollar rate to rise. Last week’s US bond market sell-off was the result, likely to further depress the economy.

China and the US have enjoyed a long marriage of convenience. Actually, China moved in uninvited. But as it put its huge savings on the table, America found it too rude to refuse. Both economies have enjoyed the good times as China’s excess savings found an outlet to induce the extra US spending the Communist state needed to keep its economy growing fast. The world as a whole enjoyed Goldilocks: low interest rates, low inflation, rising asset prices and a booming economy. As long as liquidity was sloshing around, providing the collateral for the build-up of domestic debt, the US consumer could enjoy spending beyond their means. But overinvestment in the housing market has put a spanner in the works. House prices are no longer rising; household assets are no longer rising; the borrowing and spending spree is over.

US April trade data, out last Friday, showed real non-oil goods imports down in April on the first quarter, suggesting consumer spending is faltering. Strong survey data may have prompted analysts to expect a rebound, but the real data are pointing to continued weakness. The US import downswing has been reflected in falling Asian exports. Exports to the US from Malaysia, Thailand and Singapore have all been declining since the end of last year. Today’s May trade data from China shows that exports to the US have held up well, growing by 16% in the year, although down from the 21% in Q1.

So far in the second quarter Chinese total exports have expanded at a fast pace. At 27%, although down from 29% in Q2, annual growth remains strong. China’s current account surplus continues to swell, with no respite in sight. The revival of Euroland, de-coupling from the US for the time being, has helped Chinese exports forge ahead. It has also allowed the Chinese to let the yuan appreciate vis-à-vis the dollar. No wonder that the US bond market sold off last week as it is no longer the default investment destination for China, or the rest of Asia for that matter. China’s new object of desire has turned its breakup with the US into an even more acrimonious one. Higher bond yields are not what the US needs now, even though some in the Fed might think so. The US has a stagflation problem, not an inflation one.

Continued on iTulip Select: Greenspan's Conundrum is now Bernanke's Un-Conundrum, to the Fed's Surprise - Part II

iTulip Select: The Investment Thesis for the Next Cycle.

__________________________________________________

Special iTulip discounted subscription and pay services:

For a book that explains iTulip concepts in simple terms see americasbubbleconomy

For macro-economic and geopolitical currency ETF advisory services see Crooks on Currencies

For macro-economic and geopolitical currency options advisory services see Crooks Currency Options

For the safest, lowest cost way to buy and trade gold, see The Bullionvault

To receive the iTulip Newsletter or iTulip Alerts, Join our FREE Email Mailing List

Copyright © iTulip, Inc. 1998 - 2007 All Rights Reserved

All information provided "as is" for informational purposes only, not intended for trading purposes or advice. Nothing appearing on this website should be considered a recommendation to buy or to sell any security or related financial instrument. iTulip, Inc. is not liable for any informational errors, incompleteness, or delays, or for any actions taken in reliance on information contained herein. Full Disclaimer

Comment