|

Deloitte Research chief economist doth protest too much

by Eric Janszen

"Are they seething with righteous anger with pitch forks and torches in hand? Are they ready to storm the bastions of so-called housing boosters like the closing scene in some modern day Frankenstein movie? Or does the ‘I’ in iTulip actually stand for idiot?"

- Carl Steidtmann, chief economist and director, Consumer Business - Deloitte Research - April 11, 2007)

It was inevitable. As the housing bubble collapses and the credibility of housing bubble boosters melts like a popsicle in the Texas summer sun, those of us who have been critical of them will become objects of their derision. Still, it's surprising to be called out in this way–with name calling–and by none less than Deloitte Research's chief economist and a director of Consumer Business Research, and on such a weak pretext. - Carl Steidtmann, chief economist and director, Consumer Business - Deloitte Research - April 11, 2007)

Dr. Steidtmann is mentioned in passing in a single 267 word post–one of 8,890 on our forums–on August 27, 2006 as a candidate for a potential new housing bubble Pundit Watch list, in the spirit of iTulip's stock market Bubble Pundit Watch from the stock market bubble era. Back then we featured Goldman Sach's Abby Joseph Cohen, then a certified "investment guru," and TV personality James J. Cramer, then shilling tech stocks in his inimitable way. We noted records of bad advice, and in some cases apparent misrepresentations of previous statements made from the top of the market all the down to the bitter bottom.

After the stock market crashed, Abby had finished her role on the Goldman stock sales team and was put out to pasture. Even though most of JJ Cramer's audience must have lost piles of money if they were foolish enough to take his advice, that hardly put a dent in his career. He took some time off and has been back on the air with his CNBC television show “Mad Money” for the past few years, as stock market bubble was nominally re-inflated as a side-effect of what retired IMF chief economist Kenneth Rogoff calls, "The best recovery money can buy." The reinvention of JJ has gone smoothly, save for the interview he recently had with TheStreet.com TV where he told TSC's executive editor Aaron Task that he used to manipulate stocks and the market when he was a hedge fund manager, and explained how such people today can't "do anything remotely truthful" if they want to make money. Judging by the odd camera angle, it appears Cramer was not aware that he was being recorded. The resulting jaw dropping YouTube video has been pulled. If you try to go watch it, YouTube explains, "This video is no longer available due to a copyright claim by TheStreet.com." Everyone here who believes TheStreet.com's issue with the video was copyright infringement, please send $1,000 dollars to the How to Lose $1,000 Contest here at iTulip.

|

Why Most Get it Wrong

Dr. Steidtmann isn't the only one out there to get the housing bubble story wrong. Interest and ideology conflate wherever money is concerned. The interested, versus disinterested, approach to the housing bubble is to start with a view, then search out evidence to support it, to the exclusion of all evidence that contradicts it. Then, dig your heels in and rant away. Our approach to economics and finance is to develop a hypothesis and then talk to a lot of experts to help us beat it into shape–or throw it out the window, if new evidence demands it. We developed our housing and consumer credit bubble hypothesis in 2002. We flogged it by interviewing dozens of economists, authors, and industry professionals, including in Can Anything Bring Down the Monthly Payment Consumer?, Peter Morici, University of Maryland business school professor and former chief economist of the U.S. International Trade Commission under the Clinton administration; Kevin Hassett, director of economic policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute; Lakshman Achuthan, managing director of the Economic Cycle Research Institute and a governor of the Levy Economics Institute at Bard College; James O’Sullivan, a UBS economist; Ken Goldstein, an economist with the Conference Board; Dean Baker, co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research; Russ Roberts, a professor of economics at George Mason University; Ron Blackwell, chief economist of the AFL-CIO; and Dr. Richard Curtin, director of the Surveys of Consumers at the University of Michigan; Dr. Michael Hudson, advisor to the White House, State Dept. and Defense Department at the Hudson Institute; Dr. James Galbraith in an interview; and James Scurlock, Creator of "Maxed Out" in an interview; and so on.

Source of paycheck needs to be factored into any expert's opinion. We interviewed Dr. Hudson and interpret his views from the perspective of an expert who consults to the Chinese government. We'd be surprised if Dr. Hudson's public statements on China were wholly inconsistent with the interests of his clients. Likewise Dr. Steidtmann. The Deloitte web site says, "In 2003 Consulting Magazine selected Dr. Steidtmann as one of the 25 most influential consultants for his work in consumer spending forecasting. The obvious question is, consulting to whom?

The FDIC web site bio of Dr. Steidtmann states, "He has addressed hundreds of groups on economics, technology and productivity, including the National Retail Federation, the Food Marketing Institute, and the International Mass Retail Association in addition to individual companies."

This is not a point of criticism, but an acknowledgment that one needs to know where one's economic "expert" is coming from.

In our experience, economists fall into roughly one of three groups: those on the FIRE Economy payroll, those who are angling to get onto the FIRE Economy payroll, and those who are not and are not trying to get onto the FIRE Economy payroll. We'll leave it up to readers to decide to which group Dr. Steidtmann belongs.

We'd forgotten our note about starting a housing bubble Pundit Watch list and mentioning Dr. Steidtmann in it, in a post buried among thousands of other posts on the iTulip boards. Apparently Dr. Steidtmann hasn't.

He certainly has a right to explain himself. But we have to ask, why now and why in this way?

The economist doth protest too much. He also doesn't appear to known much about asset bubbles. Let's help him out. Here's what he wrote, with our comments.

Economist's Corner: The housing bubble revisited

Has Goldilocks left the building?

By Carl Steidtmann, chief economist and director, Consumer Business, Deloitte Research

I don't want to be too sophisticated here, but 2007 is going to suck, all 12 months of the calendar year. Our future is not as bright as what we would like it to be.

— D.R. Horton Chief Executive Officer Donald Tomnitz

It’s not often that one gets such candor from a CEO. But the question that the current state of the housing market begs is: Will housing bring down the economy? This is not a new issue. Back in June 2005 I wrote a piece entitled "The Myth of the Housing Bubble." The conclusion then was that the appreciation in housing prices was not a bubble but a reflection of the very strong fundamentals in the housing market that were limiting supply and boosting demand. It also suggested that at some time in the not too distant future, interest rates would rise and demand would cool but the result would not be the catastrophe that the bubble heads were hoping for. That conclusion was met with some derision by the bubble heads that run some of the housing blogs on the internet. One went so far as to suggest darkly in the summer of 2006: "Maybe it's time to start collecting the names of the housing bubble boosters… . I've considered guys like Carl Steidtmann, who went on record at the top of the market with articles like 'The Housing Bubble Myth' in July 2005.

Has Goldilocks left the building?

By Carl Steidtmann, chief economist and director, Consumer Business, Deloitte Research

I don't want to be too sophisticated here, but 2007 is going to suck, all 12 months of the calendar year. Our future is not as bright as what we would like it to be.

— D.R. Horton Chief Executive Officer Donald Tomnitz

It’s not often that one gets such candor from a CEO. But the question that the current state of the housing market begs is: Will housing bring down the economy? This is not a new issue. Back in June 2005 I wrote a piece entitled "The Myth of the Housing Bubble." The conclusion then was that the appreciation in housing prices was not a bubble but a reflection of the very strong fundamentals in the housing market that were limiting supply and boosting demand. It also suggested that at some time in the not too distant future, interest rates would rise and demand would cool but the result would not be the catastrophe that the bubble heads were hoping for. That conclusion was met with some derision by the bubble heads that run some of the housing blogs on the internet. One went so far as to suggest darkly in the summer of 2006: "Maybe it's time to start collecting the names of the housing bubble boosters… . I've considered guys like Carl Steidtmann, who went on record at the top of the market with articles like 'The Housing Bubble Myth' in July 2005.

"I've resisted doing this because, as painful as the tech stock bubble collapse was, I worry that the housing bubble will cause much greater economic damage and inspire far more widespread desperation and hatred. This won't be middle class and upper middle class people, made temporarily rich by a stock market bubble, falling back to earth when it popped. Rather than objects of derision, the housing bubble boosters won't simply wind up as clowns splattered with virtual eggs in the Internet town square. These guys may find themselves the targets of deeper passions, and I don't want iTulip to be any part in that... ."

Quite noble of those iTulip folks not to draw attention to us housing bubble boosters. So here we are nearly two years on and interest rates have risen, mortgage lending practices have been tightened up and housing has cooled. Do we find the middle class wiped out? Are they seething with righteous anger with pitch forks and torches in hand? Are they ready to storm the bastions of so-called housing boosters like the closing scene in some modern day Frankenstein movie? Or does the ‘I’ in iTulip actually stand for idiot?

Why the housing market is not a bubble

A financial bubble has a few distinctive characteristics to it. First and foremost a bubble is a monetary phenomenon. Bubbles are created in large part by central bank mistakes. Massive increases in money supply are a requirement for all bubbles. The NASDAQ bubble was fueled by dramatic growth money supply during the late-1990s. The Fed pumped up the monetary base, first in response to the Asian currency crisis and then later out of concern about the effects of the Y2K bug on the economy.

The result was a dramatic growth in monetary reserves in 1999, much of which ended up fueling equity market speculation. When the monetary fuel for the speculative bubble was removed, the bubble broke. Over the course of the past five years we have seen a steady slowing of money reserve growth, bringing into question the possibility of any asset bubble.

|

The result was a dramatic growth in monetary reserves in 1999, much of which ended up fueling equity market speculation. When the monetary fuel for the speculative bubble was removed, the bubble broke. Over the course of the past five years we have seen a steady slowing of money reserve growth, bringing into question the possibility of any asset bubble.

1. Extremes of popular, positive investor sentiment–the general belief that the price can only go up, such as gold in 1980, tech stocks in 1999, and housing in 2005.

2. Valid Core Beliefs that are based on fact, such as the value of the Internet during the Internet bubble, that drive early adopters into the market.

3. Invalid Apocryphal Beliefs that are later invented by those who are benefiting the most from the bubble, such as investment banks and venture capital firms during the Internet bubble, but readily accepted by everyone else who is also benefiting–to explain extreme price increases that go far beyond the level justified by the Core Beliefs.

4. A well developed system of sales, marketing and distribution, that includes the mainstream press, and employs an army of analysts, consultants, lawyers, accountants, and so on, all of whom adopt first the Core Beliefs and later buy into the Apocryphal Beliefs.

5. A duration that exceeds the warnings of early bubble spotters by months or even years.

A second sign of a bubble is a big spike in prices. In the year before it peaked, NASDAQ rose by more than 130 percent. The Nikkei was up 84 percent in two years prior to its peak. When the Hunt brothers tried to corner the silver market they created a price bubble that sent silver prices from single digits to over $50 an ounce. Now those were price bubbles.

The best year for housing prices was 2005 when existing home prices rose 13 percent while for new home prices the peak came in 2004 when prices were up nearly 14 percent, hardly the stuff of a real financially driven bubble. You can see how ridiculous the claims of a housing bubble are when you compare new home prices to a real bubble.

The best year for housing prices was 2005 when existing home prices rose 13 percent while for new home prices the peak came in 2004 when prices were up nearly 14 percent, hardly the stuff of a real financially driven bubble. You can see how ridiculous the claims of a housing bubble are when you compare new home prices to a real bubble.

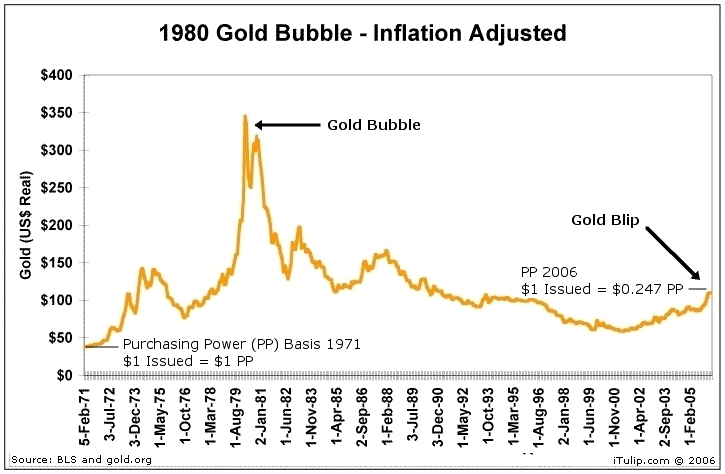

We are almost in agreement on this point. Here we show the difference between the last gold price bubble and recent price increases. The appearance of the rate of increase can be shown either as extreme or not depending on choice of price index and scale. Here by inflation-adjusting the gold price, a recent nominal price bubble disappears.

Dr. Steidtmann's shows the slightest of blips.

The New York Times graph of housing prices shows massive price appreciation.

What matters from an macro economic standpoint is the total amount of fictitious value created during an asset bubble. The stock markets are capitalized at a fraction of the housing market. Approximately $5 trillion of fictitious "bubble" capital–or 27% of the total $18.5 trillion in total market cap–was wiped out in the 2000 to 2002 stock market crash. Even at a much lower growth rate than the stock market bubble, the collapse of the housing bubble will have a larger impact because the total amount of fictitious value in the real estate market is about twice the amount created during the stock market bubble.

A third sign of a bubble is that when it breaks, everyone tries to head for the exits at the same time resulting in a collapse in prices. When the Nikkei bubble broke in 1990, prices declined just over 80 percent over the next decade. Seventeen years later the Nikkei is still half its peak value. The bursting of the NASDAQ bubble took that index down from 5132 to a low of 1108 in eighteen months, a decline of just under 80 percent. Five years later, the NASDAQ is still less than half the peak price.

So what has happened to housing prices since the bubble supposedly broke in 2005? The problem the bubble heads have is that housing prices for the most part are still collapsing upward. Since the summer of 2005, existing home prices are up 12 percent while new home prices have risen 3 percent.

So what has happened to housing prices since the bubble supposedly broke in 2005? The problem the bubble heads have is that housing prices for the most part are still collapsing upward. Since the summer of 2005, existing home prices are up 12 percent while new home prices have risen 3 percent.

Dr. James Galbraith told us, "...the negative wealth effect of a collapsing stock market is more immediate and concentrated than the impact of a housing slowdown. Everyone marks their portfolio to market within a quarter after the collapse. A housing bubble deflates slowly. Housing price value changes are not experienced by property owners until they try to turn the property into a liquid asset, either by selling or by refinancing."

A housing market correction is a slow process.

Unlike Internet bubble stocks, Japanese stocks or silver, people still need housing and the demand for housing continues to grow. Population growth creates the need for 1 to 1.2 million new units. Tear downs and depreciation add another 300K to 500K units and second home buying can add another 200K to 400K units or more each and every year. Even in a weak demand year that adds up to 1.5 million units and in a strong year more than 2 million.

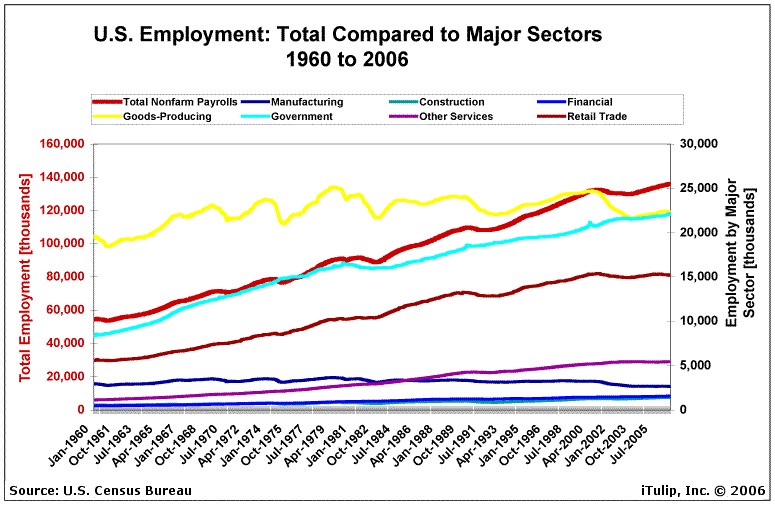

The reason 1 million households could not pay their mortgages around the Houston area is because oil prices collapsed and the regional oil industry along with it. Government is now at par with the goods producing sector as an employer. If not for the fiscal deficits the US has been running since 2001, the government cannot support this level of employment. If not for continued foreign lending on a scale unprecedented in world history, these deficits cannot be maintained without creating extremely high levels of inflation as the US will be forced to monetize its own debt, or reduce the creation of new debt. As the US economy slows, so shall foreign lending and the ability of the US government to create jobs without also creating levels of inflation which will not be acceptable to bond holders. Neither unemployment nor inflation are positive for housing prices, as the former reduces incomes which can be spent on housing, and the latter raises interest rates which increases monthly mortgage costs. We expect to see both unemployment and inflation as the recession progresses and the Fed, the Whitehouse, and Congress attempt to navigate between the politically untenable and the politically disastrous, between inflation and unemployment, as the policy space between them narrows.

There are a lot of reasons why home prices have been rising in this decade. Demographics remain favorable, financing is still cheap, land-use restrictions continue to tighten, second home buying continues to rise and urban gentrification is making for better neighborhoods. All of these have to do with the fundamentals of supply and demand.

We explain in detail in Fueling the FIRE Economy how the housing bubble happened from the standpoint of monetary policy. In summary:

As mortgage-x.com explains, the variable rate that lenders offer for the introductory period of an ARM is based on short term interest rate indexes: "CMT, COFI, and LIBOR indexes are the most frequently used. Approximately 80 percent of all the ARMs today are based on one of these indexes." All three indexes are close to each other.

For our purposes, we compare 6-month LIBOR and National Average

Contract Mortgage Rate.

Contract Mortgage Rate.

Short rates drop to extremely low levels between 2001 and 2004.

Not surprisingly there was a jump in borrowing.

Not surprisingly there was a jump in borrowing.

Home equity borrowing sky-rocketed.

Why housing won’t sink the economy

While the action in housing prices in no way resembles a bubble, housing nonetheless has been hurting over the past year. Overbuilding and a slowdown in home sales due to higher interest rates and tighter lending standards have created an overhang of unsold inventory. Housing starts have fallen more than 30 percent. Home price appreciation has slowed and by some measures has declined. Both new and existing home sales are down.

Declines in housing construction in the past have been an early warning of a pending recession in the broad economy. Over the past the declines in home construction have taken 1 percent off of top line GDP growth. That loss has slowed real GDP growth from the 3-3.5 percent range down to the 2-2.5 percent range. It means that the economy is more at risk for a recession, but by itself, not enough to cause a recession.

At its peak, home construction made up a little more than 6 percent of GDP. To get a full blown recession, the problems in housing have to spill over into some other sector of the economy. The most likely candidate for that spillover is the consumer. Making up 70 percent of GDP, any loss of consumer spending could take the economy down.

While the action in housing prices in no way resembles a bubble, housing nonetheless has been hurting over the past year. Overbuilding and a slowdown in home sales due to higher interest rates and tighter lending standards have created an overhang of unsold inventory. Housing starts have fallen more than 30 percent. Home price appreciation has slowed and by some measures has declined. Both new and existing home sales are down.

Declines in housing construction in the past have been an early warning of a pending recession in the broad economy. Over the past the declines in home construction have taken 1 percent off of top line GDP growth. That loss has slowed real GDP growth from the 3-3.5 percent range down to the 2-2.5 percent range. It means that the economy is more at risk for a recession, but by itself, not enough to cause a recession.

At its peak, home construction made up a little more than 6 percent of GDP. To get a full blown recession, the problems in housing have to spill over into some other sector of the economy. The most likely candidate for that spillover is the consumer. Making up 70 percent of GDP, any loss of consumer spending could take the economy down.

We were on a call recently with Lehman Bros. economists who disagree. They explained during Q&A: "From the standpoint of borrower risk, the crisis is much worse than the S&L crisis. From a risk ownership standpoint, not nearly as bad." Meaning the banks will be okay, but homeowners and consumers will get hammered. Their "Housing Crash" scenario calls for 1.6% GDP growth in 2008 as many segments of the economy go into recession, housing first.

Employment and Real Wage Growth

One of the remarkable characteristics about American consumers is that if you give them cash, they go out and spend it. Real consumer spending has not declined on a quarterly basis since the fourth quarter of 1991. Through currency crises, government shut downs, natural disasters, stock market meltdowns, accounting and financial scandals, terrorist attacks and real recessions American consumers continued to spend. As Morgan Stanley's chronically bearish Stephen Roach has pointed out: "The forecasting landscape has long been littered with carcasses of those who have been dumb enough to bet against the American consumer. From time to time, there have been unconfirmed sightings of my skeletal remains in that heap."

|

Without ever more rapid public and private sector debt growth, current GDP growth cannot be maintained. This measure tells you how much new debt is needed to generate economic growth.

In 1983, $1 of debt was needed to generate $1 of GDP. Now nearly $3 is needed.

The first bears called an end to this process back in the early 1990s. We are predicting a revelation of fraud in one or both of the GSEs will get the ball rolling. When? Maybe soon, maybe not until after the 2008 presidential election. You have to be a political insider to know for certain when someone's going to pull the plug on that racket.

Much is made of the wealth effects of falling housing prices and the loss of refinance money. Refinance activity peaked in the fourth quarter of 2005 and has declined by half since then. Real consumer spending has slowed, but continues to grow at a 3.5 percent clip. Refi could go to zero, but even if that did happen, but it is not likely to have much more of an impact on consumer spending than it already has, which is very little.

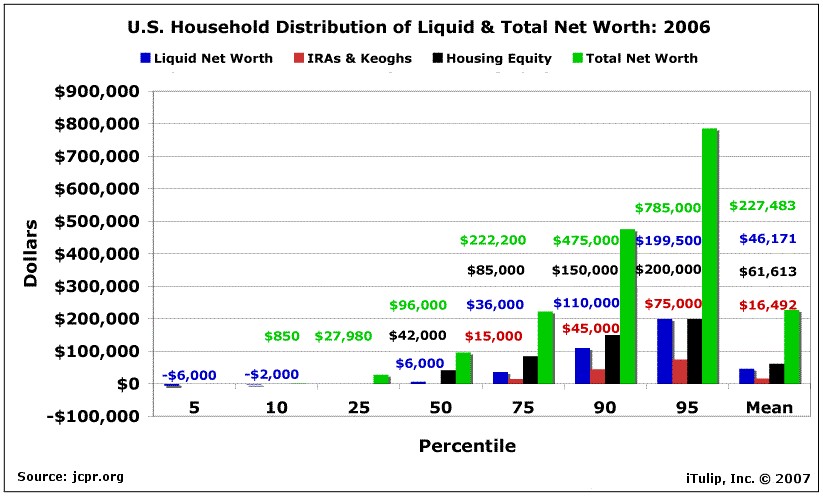

Declining home prices could make consumers feel poorer and through a wealth effect, dampen spending. However back in 2001-2, when household wealth really did decline following the breaking of the NASDAQ bubble, consumers continued to spend. And so far, despite the worries of the bubbleheads at places like iTulip, household net worth has risen by some $5 trillion since mid-2005.

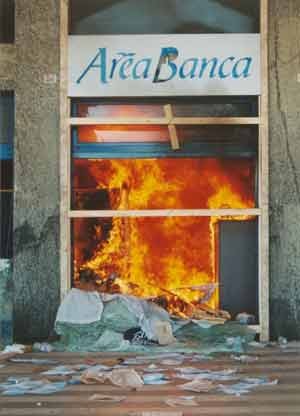

The debt-to-net worth picture is even worse. The top 10% are in good shape, the top 20% in okay shape. Everyone else is in bad shape. The negative net worth of the bottom 40% is so extreme they need their own scale, which goes up into the 1,000s of percent on the left. Note the debt/net worth ratio of the bottom 40% is very sensitive to recessions. That group's household debt was nearly 20 times net worth in 1962, 6% of net worth in 1984 (briefly at parity with the top 10%), more than 20 times net worth in 1998, about 40% in 2001, and back up to 16 times net worth today. That'd be the torch and pitchfork crowd, assuming they can't be kept distracted by reality TV and shipped off to war as that ratio plunges back toward positive net worth levels during the next recession.

What will keep consumers spending is cash flow. Right now consumer cash flow is getting a dual boost from the somewhat unusual combination of steady employment growth and rising real wages.

On the employment front, the goods-producing and government sectors now employ the same number of people. Employment growth has largely been in government, and that doesn't count the number of jobs which are for companies which produce products for sale to the government, which if included make government the nation's largest employer. How long can we keep printing money to employ people to keep the economy going, with the printed money monetized by trade partners? Latin American countries tried that back in the 1980s. Didn't work out.

Conclusions and observations

No business cycle lasts forever and the current one will be no different. In the middle of the expansions of the 1960s, 1980s and 1990s, the Federal Reserve tightened credit policy to dampen inflation. Interest rate sensitive sectors of the economy in general and housing in particular slowed. The weakness in economic growth allowed the Fed to ease policy, producing a jump in the stock market and several more years of growth. While a recession at this point in the business cycle can not be ruled out completely, given the strength of consumer spending, continued slow growth in the economy seems the most likely outcome.

No business cycle lasts forever and the current one will be no different. In the middle of the expansions of the 1960s, 1980s and 1990s, the Federal Reserve tightened credit policy to dampen inflation. Interest rate sensitive sectors of the economy in general and housing in particular slowed. The weakness in economic growth allowed the Fed to ease policy, producing a jump in the stock market and several more years of growth. While a recession at this point in the business cycle can not be ruled out completely, given the strength of consumer spending, continued slow growth in the economy seems the most likely outcome.

|

Dr. Steidtmann is dreaming if he believes that there will be no serious political fallout from the righting of the upside down consumer credit system. Maybe consultants to the consumer products, lending, and real estate industries won't get tagged. Maybe they will merely fade away, in the manner of Abby Cohen, or re-invent themselves as JJ Cramer did. Hard to say who exactly will get most of the blame. The usual targets of popular enmity are the banks themselves, at least that's been the case in other countries. People get cranky when their homes are taken away and their savings are wiped out.

We'll check back in with Dr. Steidtmann in a couple of years, after "investors" view property ownership with the same enthusiasm as they now have for pets.com stock. Maybe by that time we'll be deep into an Energy or Infrastructure bubble, and the housing bubble will be merely another finished chapter in the book on bubbles that's still being written. But if it's the last bubble, we'll keep our eyes open for the Frankenstein crowd.

Addendum: See our prediction of events to follow the collapse of the NASDAQ bubble (Nov. 1999):

How about fraud? If this mania is like every other, the smell of easy money has attracted a lot of shady characters and motivated unseemly behavior among the otherwise ethical and lawful. Don't be surprised if the management of a few Internet favorites turns out to have cut a few legal corners. Finally, since so much consumer spending is done due to the addition of stock market "wealth" on the family balance sheet, expect consumer spending to drop fast, slowing the economy.

So what happens if the bubble pops? The Fed will of course pump up the cash supply again -- "flood the streets with money" as a previous Fed chairman was fond of saying -- as in late 1998 and the early part of 1999. And the bubble picks up where it left off, growing to the next stage of outrageous proportion. As scary as that is, the alternative is worse. If the new liquidity doesn't re-inflate the markets, we crash hard. The result of that unlikely event is a topic for another day.

What happens to bubble pundits who take us on (March 2000):So what happens if the bubble pops? The Fed will of course pump up the cash supply again -- "flood the streets with money" as a previous Fed chairman was fond of saying -- as in late 1998 and the early part of 1999. And the bubble picks up where it left off, growing to the next stage of outrageous proportion. As scary as that is, the alternative is worse. If the new liquidity doesn't re-inflate the markets, we crash hard. The result of that unlikely event is a topic for another day.

Your article "When (and Why) the Bubble Must Burst" is proof that you are eloquent and very well learned. However, your vision of the stock market is misguided and wrong. If you have been predicting the end of the so-called "mania" since 1998, you and any one who followed you would have missed the boat on the largest economic expansion of our time. - Steven Cadoff, PaineWebber

I have no quarrel with anyone who is in this market or who encourages playing the market. But I do take issue with those who fail to mention the risks. This leads many to put retirement money into the market, or take out a second mortgage on the house to buy stocks, or borrow money against stocks to buy property. My message is for them. - Eric Janszen

iTulip Select the inside scoop.I have no quarrel with anyone who is in this market or who encourages playing the market. But I do take issue with those who fail to mention the risks. This leads many to put retirement money into the market, or take out a second mortgage on the house to buy stocks, or borrow money against stocks to buy property. My message is for them. - Eric Janszen

__________________________________________________

Special iTulip discounted subscription and pay services:

For the safest, lowest cost way to buy and trade gold, see The Bullionvault

To receive the iTulip Newsletter or iTulip Alerts, Join our FREE Email Mailing List

Copyright © iTulip, Inc. 1998 - 2007 All Rights Reserved

All information provided "as is" for informational purposes only, not intended for trading purposes or advice. Nothing appearing on this website should be considered a recommendation to buy or to sell any security or related financial instrument. iTulip, Inc. is not liable for any informational errors, incompleteness, or delays, or for any actions taken in reliance on information contained herein. Full Disclaimer

)

)

Comment