http://seekingalpha.com/article/1562...hp_mostpopular

With everyone (well, almost everyone - I am one of the lonely skeptics) convinced that we have stepped back from the "edge of the abyss", the title of this article may be viewed as laughable. When you connect the dots, as I will in this article, you will at least stop laughing, and, maybe, realize that we still have a big problem.

We have a confluence of five factors that have the potential to create damage to banking not seen in 80 years, and that includes the Great Depression. We'll hit these factors one at a time.

First Factor: Banks Are Not Doing Enough Business

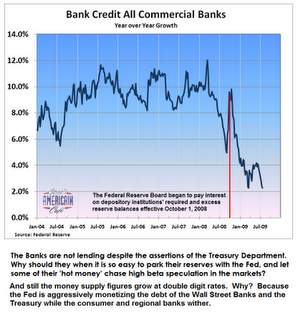

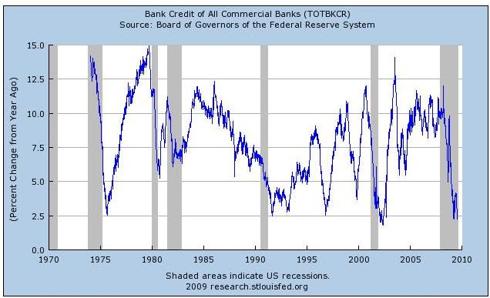

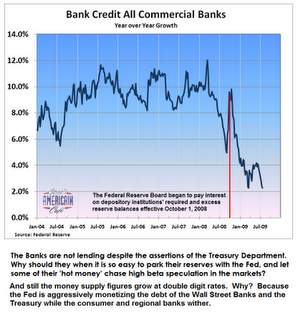

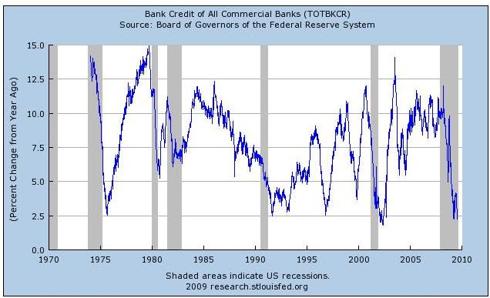

Commercial bank credit growth has dropped to 2%, according to Jesse's Cafe Americain (here). The recent history of credit growth is shown in the following graph.

Now, it is a good thing that banks are conserving capital, since they need to increase capital to offset bad loans.

But, if asset valuations deteriorate (and that is quite possible), the banks need to increase earnings to "earn their way" out of their problem. Interest paid by the Fed for reserves on deposit there (by the commercial banks) are not producing nearly the same level of income as new credit issued commercially under our fractional reserve banking system with much higher interest .

If credit issuance does not increase year over year, banks can not improve their financial condition unless the quality of their existing loan portfolio improves.

As discussed in the third factor, below, just the opposite is anticipated for loan portfolios.

So the first factor in this perfect storm is that the banks are not doing enough business.

Second Factor: Banks Are Failing at a Rate Not Anticipated Two Months Ago

In his article, Jesse mentions reports by Bloomberg that 150 banks are in trouble. Some of these will be larger than many of the 77 (mostly community) banks that have gone under FDIC receivership so far in 2009.

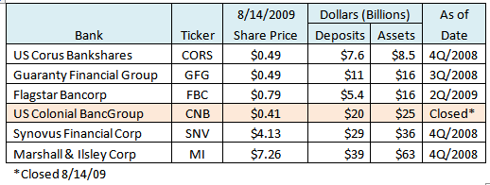

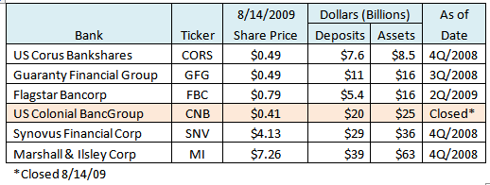

Banks mentioned as being in trouble by Bloomberg (here) include Wisconsinís Marshall & Ilsley Corp. (MI), Georgiaís Synovus Financial Corp. (SNV), Michiganís Flagstar Bancorp (FBC), Chicago-based Corus Bankshares Inc. (CORS), Austin-based Guaranty Financial Group Inc (GFG), and Colonial BancGroup Inc. (CNB) in Montgomery, Alabama.

These six banks became five at the close of business Friday, Aug. 14, as Colonial BancGroup was taken over by the State of Alabama and the FDIC. This was the largest bank failure since IndyMac Bank went under in the summer of 2008.

The following table shows some data regarding the six banks singled out by name in the Bloomberg article.

On July 5, Bill Cassill wrote (here) that he projected 125 bank failures for 2009 and 230 in 2010.

However, as of that date, Bill projected 82 closings by 9/30 and we have already reached 77 on 8/14. We still have half the quarter to go. With the 150 additional banks estimated by the Bloomberg article, and the 77 already closed thus far this year, we could be closer to 230 closings in 2009 than the 125 estimated just six weeks ago. Bill is not alone. I recall hearing other estimates of bank failures for 2009 of the order of 100 for the entire year.

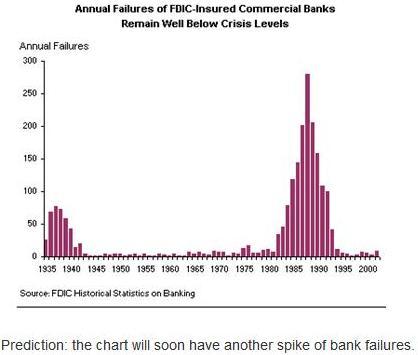

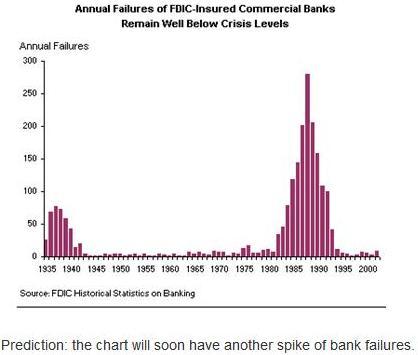

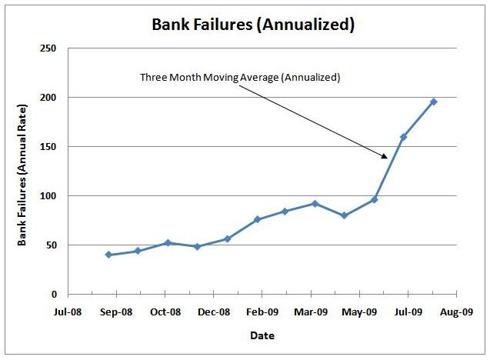

The following graph (and the prediction below it) was provided on July 12 (here) by Colin Peterson.

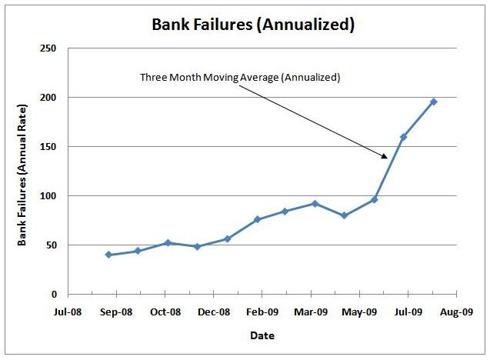

How is Colin's prediction doing? The following graph shows how bank failure rates have been trending.

Give Colin the handicapper award here. Not only have bank failure rates spiked, the current annualized rate would be in a virtual three-way tie for second highest in history if maintained for another nine months.

And a lot of the banks going under are a lot larger than the average savings and loan in the previous crisis.

According to About.com (here): Between 1986-1995, over 1,000 banks with total assets of over $500 billion failed. Even if the current crisis falls far short of the 1,000 bank total, the total assets involved will still be vastly larger. Just in the failures of Wachovia Bank and Washington Mutual, the total assets were $619 billion. Add to that the IndyMac failure and the six banks in the troubled list above and there is another $164 billion.

And I am not even mentioning the shadow banks (Merrill, Bear Stearns, Lehman and AIG are examples), which add hundreds of billions more.

There should be no false comfort taken in the prospect that we may have far fewer bank failures this time compared to the S&L crisis. The dollar amounts are likely to be many times larger.

Third Factor: Defaults Are Going to Increase for Several More Quarters

With home mortgage foreclosure rates remaining very high (and possibly increasing) and with the bulk of the commercial real estate defaults yet to come, the failure rate of banks is likely to increase further in the next nine to twelve months, not decline. The situation will be compounded if commercial and industrial (C&I) loans also default at higher rates because of a weak or non-existent recovery.

Reading some of the latest quarterly reports for a number of banks, C&I loan portfolios have generally been performing better than many other categories, but will that continue?

A reference for this subject is a Jeffrey Bernstein article published in late May entitled "C&I Loans Are Starting to Unravel" (here), which discussed the status of a wide variety of loan portfolio categories. C&I defaults may, at this time, be like an iceberg, with 90%+ still not visible above water.

Default rates in all credit areas have started to rise, although some have yet to reach levels of other recent recessions (see Bernstein article here). Residential mortgage defaults have been the elephant in the room. We have to continue to worry that problem may increase further, but we better also worry about all the baby elephants.

We may have "saved the financial system", but it seems likely that we will lose banks at levels far exceeding anything seen in our history. Even if we fall short in number of the approximately 1,000 S&Ls, the assets involved will be much larger.

We need one hell of a recovery here to prevent disaster. Muddle through will not do it. A return to 3% GDP growth may not do it. We need a couple of years at 4% (or higher) GDP growth to have any chance that some of these banks can earn their way out of the quagmire.

I don't think that type of economic growth can be realized. It certainly is not going to happen if commercial bank credit growth doesn't expand drastically and quickly.

Fourth Factor: The FDIC Is in Trouble

Rolfe Winkler (here) points out that the accelerating rate of bank failures may exhaust the Deposit Insurance Fund (DIF) at the FDIC, requiring that agency to draw on its credit line with the Fed. Rolfe calculates that the FDIC is currently on the hook for $8.3 trillion in insured deposits, had only $41.5 billion in reserves as of March 31 and has drawn that lower since.

Since only a small portion of deposits actually are paid out of DIF (failed banks have assets that cover most deposits), FDIC needs only a small fraction of covered deposits in reserve.

However, less than 0.05% is most likely several fold too small in a distressed banking system. The section title says the FDIC is in trouble. That is a polite way of saying they are bankrupt.

Fifth Factor: We May Be Going to Historic Lows in Bank Credit

Because we are approaching the one year anniversary of a growth spike in bank credit in September, 2008 (see the first graph in this article), there is likely to be continued pressure on the year-over-year growth rate. The year over year growth of credit may be driven much lower than the current 2% within the next couple months due to the negative effect on comparison due to the spike a year earlier.

As shown below, this would be an historic low.

There is one possible piece of good news here. Looking at a longer history from the Fed FRED data base (here), the current situation is similar to those seen after the end of the recessions of 1973-75, 1990-91, and 2001. A similar minimum was also reached in 1997.

It should be noted that several minima in commercial bank credit have occurred that were not associated with the end of a recession. This indicates there are non-recessionary factors related to dips in commercial credit.

All recessions have dips in commercial bank credit, but all dips in commerical bank credit are not associated with recessions.

This time, the minimum may not have been reached yet because of the spike in credit volume in September, 2008 (mentioned above). If September 2009 does see a minimum in commercial bank credit, this would be another sign that the recession probably ended earlier in the year.

However, the banks need far more than an end to the recession; they need a recovery of unlikely proportions.

One cautionary note: Although the minimum was much higher in the 1981-82 recession, the lowest point occurred about a year before the recession actually ended. That could always happen again.

Is There Any Hope?

Well, since so many people are predicting a weak recovery, that has a good chance of not happening, based on the observation that, in economic matters, agreement by a majority is often wrong. So, if the majority is wrong, which way do you think things will go? Back into recession? The robust recovery predicted by only a few?

I'll leave a definitive answer to the reader - after all I can't do all the work. I'll just share my bias, based on all the factors I can collect: An advance in real GDP of 4-5% in 2010 and 2011 (2-2.5% per year) seems to me to be the very best that might be obtained, but less is more likely.

Without a strong recovery, there is little hope of a good outcome for the non-oligarchy banks. With a return to recession, in 2010 (and possibly 2011 and 2012) there could be carnage in regional and local banks not seen since the early 1900s, and maybe even worse than what occurred then.

I hope we don't have to compare what happens in 2010 to 1873.

The banking crisis of 1873 started what has been called "The Long Depression". This consisted of a period of rolling recessions that continued for almost 40 years and included additional banking crises in 1893 and 1907. This long period of economic and financial turmoil was a major motivator in the formation of the Federal Reserve Bank. The Fed was the first true central national bank for the U.S. since the dissolution of the Second Bank of the United States in 1837 by Andrew Jackson.

With everyone (well, almost everyone - I am one of the lonely skeptics) convinced that we have stepped back from the "edge of the abyss", the title of this article may be viewed as laughable. When you connect the dots, as I will in this article, you will at least stop laughing, and, maybe, realize that we still have a big problem.

We have a confluence of five factors that have the potential to create damage to banking not seen in 80 years, and that includes the Great Depression. We'll hit these factors one at a time.

First Factor: Banks Are Not Doing Enough Business

Commercial bank credit growth has dropped to 2%, according to Jesse's Cafe Americain (here). The recent history of credit growth is shown in the following graph.

Now, it is a good thing that banks are conserving capital, since they need to increase capital to offset bad loans.

But, if asset valuations deteriorate (and that is quite possible), the banks need to increase earnings to "earn their way" out of their problem. Interest paid by the Fed for reserves on deposit there (by the commercial banks) are not producing nearly the same level of income as new credit issued commercially under our fractional reserve banking system with much higher interest .

If credit issuance does not increase year over year, banks can not improve their financial condition unless the quality of their existing loan portfolio improves.

As discussed in the third factor, below, just the opposite is anticipated for loan portfolios.

So the first factor in this perfect storm is that the banks are not doing enough business.

Second Factor: Banks Are Failing at a Rate Not Anticipated Two Months Ago

In his article, Jesse mentions reports by Bloomberg that 150 banks are in trouble. Some of these will be larger than many of the 77 (mostly community) banks that have gone under FDIC receivership so far in 2009.

Banks mentioned as being in trouble by Bloomberg (here) include Wisconsinís Marshall & Ilsley Corp. (MI), Georgiaís Synovus Financial Corp. (SNV), Michiganís Flagstar Bancorp (FBC), Chicago-based Corus Bankshares Inc. (CORS), Austin-based Guaranty Financial Group Inc (GFG), and Colonial BancGroup Inc. (CNB) in Montgomery, Alabama.

These six banks became five at the close of business Friday, Aug. 14, as Colonial BancGroup was taken over by the State of Alabama and the FDIC. This was the largest bank failure since IndyMac Bank went under in the summer of 2008.

The following table shows some data regarding the six banks singled out by name in the Bloomberg article.

On July 5, Bill Cassill wrote (here) that he projected 125 bank failures for 2009 and 230 in 2010.

However, as of that date, Bill projected 82 closings by 9/30 and we have already reached 77 on 8/14. We still have half the quarter to go. With the 150 additional banks estimated by the Bloomberg article, and the 77 already closed thus far this year, we could be closer to 230 closings in 2009 than the 125 estimated just six weeks ago. Bill is not alone. I recall hearing other estimates of bank failures for 2009 of the order of 100 for the entire year.

The following graph (and the prediction below it) was provided on July 12 (here) by Colin Peterson.

How is Colin's prediction doing? The following graph shows how bank failure rates have been trending.

Give Colin the handicapper award here. Not only have bank failure rates spiked, the current annualized rate would be in a virtual three-way tie for second highest in history if maintained for another nine months.

And a lot of the banks going under are a lot larger than the average savings and loan in the previous crisis.

According to About.com (here): Between 1986-1995, over 1,000 banks with total assets of over $500 billion failed. Even if the current crisis falls far short of the 1,000 bank total, the total assets involved will still be vastly larger. Just in the failures of Wachovia Bank and Washington Mutual, the total assets were $619 billion. Add to that the IndyMac failure and the six banks in the troubled list above and there is another $164 billion.

And I am not even mentioning the shadow banks (Merrill, Bear Stearns, Lehman and AIG are examples), which add hundreds of billions more.

There should be no false comfort taken in the prospect that we may have far fewer bank failures this time compared to the S&L crisis. The dollar amounts are likely to be many times larger.

Third Factor: Defaults Are Going to Increase for Several More Quarters

With home mortgage foreclosure rates remaining very high (and possibly increasing) and with the bulk of the commercial real estate defaults yet to come, the failure rate of banks is likely to increase further in the next nine to twelve months, not decline. The situation will be compounded if commercial and industrial (C&I) loans also default at higher rates because of a weak or non-existent recovery.

Reading some of the latest quarterly reports for a number of banks, C&I loan portfolios have generally been performing better than many other categories, but will that continue?

A reference for this subject is a Jeffrey Bernstein article published in late May entitled "C&I Loans Are Starting to Unravel" (here), which discussed the status of a wide variety of loan portfolio categories. C&I defaults may, at this time, be like an iceberg, with 90%+ still not visible above water.

Default rates in all credit areas have started to rise, although some have yet to reach levels of other recent recessions (see Bernstein article here). Residential mortgage defaults have been the elephant in the room. We have to continue to worry that problem may increase further, but we better also worry about all the baby elephants.

We may have "saved the financial system", but it seems likely that we will lose banks at levels far exceeding anything seen in our history. Even if we fall short in number of the approximately 1,000 S&Ls, the assets involved will be much larger.

We need one hell of a recovery here to prevent disaster. Muddle through will not do it. A return to 3% GDP growth may not do it. We need a couple of years at 4% (or higher) GDP growth to have any chance that some of these banks can earn their way out of the quagmire.

I don't think that type of economic growth can be realized. It certainly is not going to happen if commercial bank credit growth doesn't expand drastically and quickly.

Fourth Factor: The FDIC Is in Trouble

Rolfe Winkler (here) points out that the accelerating rate of bank failures may exhaust the Deposit Insurance Fund (DIF) at the FDIC, requiring that agency to draw on its credit line with the Fed. Rolfe calculates that the FDIC is currently on the hook for $8.3 trillion in insured deposits, had only $41.5 billion in reserves as of March 31 and has drawn that lower since.

Since only a small portion of deposits actually are paid out of DIF (failed banks have assets that cover most deposits), FDIC needs only a small fraction of covered deposits in reserve.

However, less than 0.05% is most likely several fold too small in a distressed banking system. The section title says the FDIC is in trouble. That is a polite way of saying they are bankrupt.

Fifth Factor: We May Be Going to Historic Lows in Bank Credit

Because we are approaching the one year anniversary of a growth spike in bank credit in September, 2008 (see the first graph in this article), there is likely to be continued pressure on the year-over-year growth rate. The year over year growth of credit may be driven much lower than the current 2% within the next couple months due to the negative effect on comparison due to the spike a year earlier.

As shown below, this would be an historic low.

There is one possible piece of good news here. Looking at a longer history from the Fed FRED data base (here), the current situation is similar to those seen after the end of the recessions of 1973-75, 1990-91, and 2001. A similar minimum was also reached in 1997.

It should be noted that several minima in commercial bank credit have occurred that were not associated with the end of a recession. This indicates there are non-recessionary factors related to dips in commercial credit.

All recessions have dips in commercial bank credit, but all dips in commerical bank credit are not associated with recessions.

This time, the minimum may not have been reached yet because of the spike in credit volume in September, 2008 (mentioned above). If September 2009 does see a minimum in commercial bank credit, this would be another sign that the recession probably ended earlier in the year.

However, the banks need far more than an end to the recession; they need a recovery of unlikely proportions.

One cautionary note: Although the minimum was much higher in the 1981-82 recession, the lowest point occurred about a year before the recession actually ended. That could always happen again.

Is There Any Hope?

Well, since so many people are predicting a weak recovery, that has a good chance of not happening, based on the observation that, in economic matters, agreement by a majority is often wrong. So, if the majority is wrong, which way do you think things will go? Back into recession? The robust recovery predicted by only a few?

I'll leave a definitive answer to the reader - after all I can't do all the work. I'll just share my bias, based on all the factors I can collect: An advance in real GDP of 4-5% in 2010 and 2011 (2-2.5% per year) seems to me to be the very best that might be obtained, but less is more likely.

Without a strong recovery, there is little hope of a good outcome for the non-oligarchy banks. With a return to recession, in 2010 (and possibly 2011 and 2012) there could be carnage in regional and local banks not seen since the early 1900s, and maybe even worse than what occurred then.

I hope we don't have to compare what happens in 2010 to 1873.

The banking crisis of 1873 started what has been called "The Long Depression". This consisted of a period of rolling recessions that continued for almost 40 years and included additional banking crises in 1893 and 1907. This long period of economic and financial turmoil was a major motivator in the formation of the Federal Reserve Bank. The Fed was the first true central national bank for the U.S. since the dissolution of the Second Bank of the United States in 1837 by Andrew Jackson.

Comment