U.S. Slowdown Underway, Canada in for a Bumpy Ride (pdf)

September 18, 2006 (TD Capital Economics)

AntiSpin: When the US sneezes, the world catches cold, as the saying goes. Will this mean that, once again, a "Black Swan" event will occur somewhere at the periphery of the US-centric global financial system as the credit cycle (bubble) ends, sending money flooding into the US as during the 1997 Asia currency crisis? Or will the US itself be the epicenter of next global crisis, that pivots on the US dollar, as we have been predicting? Will massive currency reserves built up by governments around the world, and especially in Asia, since 1998 make these nations appear to be a safer home for flight capital? Will even US capital head there?

The essence of the argument that the US negative trade balance and reliance on foreign capital to fund cash flow is that USA, Inc. is a better run business than China, Inc., Japan, Inc., EU, Inc, or any other potential home for flight capital in a global crisis. The best argument for that case is made in "The Overstretch Myth" by David H. Levey and Stuart S. Brown, Foreign Affairs, March/April 2005.

But these are factors that will play out over many years or decades. More relevant to the crisis at hand is the political antecedent of Ka-Poom Theory, poor distribution of wealth and income. What can we expect as the domestic political reaction to a slowing in "the growth of U.S. consumers' standard of living" that the TD Capital Economics team explains "could very well feel like a recession to many people" under these conditions?

The political response to the coming recession is already cued up on the airwaves by populists like Lou Dobbs and Patrick Buchanan, who prescribe a cure for Globologne* that's worse than the disease. To be sure, the playing field represented by Globologne needs to be leveled. But to the extent that the markets are already pricing in the US political response to the next crisis, the era of "exorbitant privilege" may come to a sudden end in a "Black Swan" event. The IMF recently said that a "disorderly' drop in the dollar is the biggest risk to world financial markets." This will be both the cause and the result of flight capital going the "wrong" way in a US-centric financial crisis, after which not only the playing field may be leveled but the global economy as well.

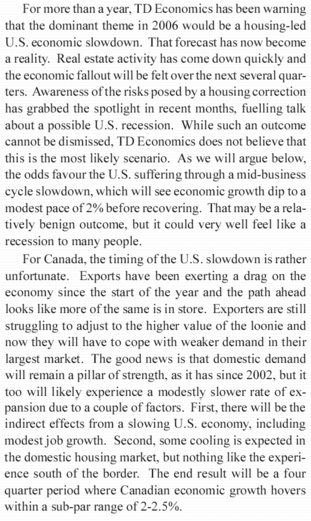

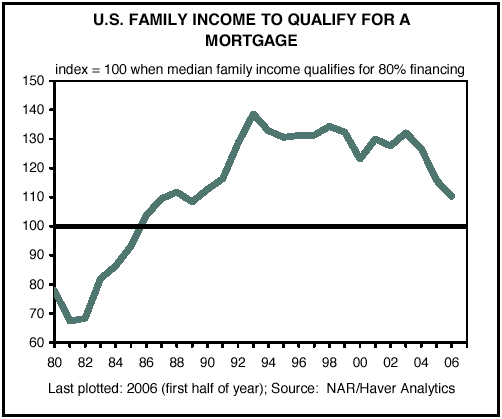

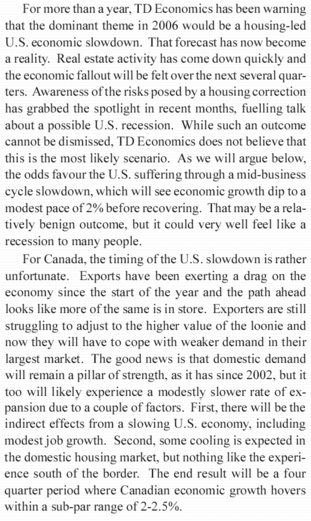

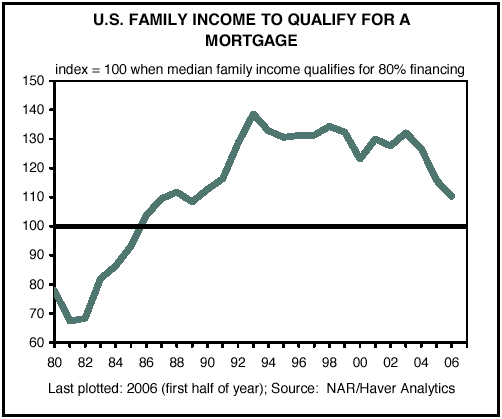

To the extent that relative economic strength drives investment flows and currency values, might the economy with the least number of credit-worthy borrowers represent the greatest risk to GDP growth in an economy that has become as dependent on real estate for growth as the US has over the past six years? Here TD Capital Economics includes a chart that may be more significant than any other in the report. It suggests that just as US banks are tightening lending standards, reducing zero money down loans and returning to the more standard requirement for 20% down and proof of income to support the other 80% financed, the number of US families that qualifies is steadily declining.

* Globologne: A system of global trade that unequally benefits owners of capital over labor.

September 18, 2006 (TD Capital Economics)

AntiSpin: When the US sneezes, the world catches cold, as the saying goes. Will this mean that, once again, a "Black Swan" event will occur somewhere at the periphery of the US-centric global financial system as the credit cycle (bubble) ends, sending money flooding into the US as during the 1997 Asia currency crisis? Or will the US itself be the epicenter of next global crisis, that pivots on the US dollar, as we have been predicting? Will massive currency reserves built up by governments around the world, and especially in Asia, since 1998 make these nations appear to be a safer home for flight capital? Will even US capital head there?

The essence of the argument that the US negative trade balance and reliance on foreign capital to fund cash flow is that USA, Inc. is a better run business than China, Inc., Japan, Inc., EU, Inc, or any other potential home for flight capital in a global crisis. The best argument for that case is made in "The Overstretch Myth" by David H. Levey and Stuart S. Brown, Foreign Affairs, March/April 2005.

Would-be Cassandras have been predicting the imminent downfall of the American imperium ever since its inception. First came Sputnik and "the missile gap," followed by Vietnam, Soviet nuclear parity, and the Japanese economic challenge--a cascade of decline encapsulated by Yale historian Paul Kennedy's 1987 "overstretch" thesis.

The resurgence of U.S. economic and political power in the 1990s momentarily put such fears to rest. But recently, a new threat to the sustainability of U.S. hegemony has emerged: excessive dependence on foreign capital and growing foreign debt. As former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers has said, "there is something odd about the world's greatest power being the world's greatest debtor."

The heart of the argument that foreign capital flows will never reverse is summed up as follows.The resurgence of U.S. economic and political power in the 1990s momentarily put such fears to rest. But recently, a new threat to the sustainability of U.S. hegemony has emerged: excessive dependence on foreign capital and growing foreign debt. As former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers has said, "there is something odd about the world's greatest power being the world's greatest debtor."

Despite the persistence and pervasiveness of this doomsday prophecy, U.S. hegemony is in reality solidly grounded: it rests on an economy that is continually extending its lead in the innovation and application of new technology, ensuring its continued appeal for foreign central banks and private investors. The dollar's role as the global monetary standard is not threatened, and the risk to U.S. financial stability posed by large foreign liabilities has been exaggerated. To be sure, the economy will at some point have to adjust to a decline in the dollar and a rise in interest rates. But these trends will at worst slow the growth of U.S. consumers' standard of living, not undermine the United States' role as global pacesetter. If anything, the world's appetite for U.S. assets bolsters U.S. predominance rather than undermines it.

At the peak of its global power the United Kingdom was a net creditor, but as it entered the twentieth century, it started losing its economic dominance to Germany and the United States. In contrast, the United States is a large net debtor. But in its case, no plausible challenger to its economic leadership exists, and its share of the global economy will not decline. Focusing exclusively on the NIIP obscures the United States' institutional, technological, and demographic advantages. Such advantages are further bolstered by the underlying complementarities between the U.S. economy and the economies of the developing world--especially those in Asia. The United States continues to reap major gains from what Charles de Gaulle called its "exorbitant privilege," its unique role in providing global liquidity by running chronic external imbalances. The resulting inflow of productivity-enhancing capital has strengthened its underlying economic position. Only one development could upset this optimistic prognosis: an end to the technological dynamism, openness to trade, and flexibility that have powered the U.S. economy. The biggest threat to U.S. hegemony, accordingly, stems not from the sentiments of foreign investors, but from protectionism and isolationism at home.

To refute these points: Many of the key institutions that have given the US an institutional advantage are not improving while they are improving elsewhere in the world, and the significance of the advantages cited are all about relative not absolute advantage. The banking system and financial markets, for example, have grown more corrupt and inefficient in the US while they have become more transparent and efficient elsewhere. On innovation, the Bush administration's fatwa against stem cell research dooms the US to second or third rate status as an innovator of some of the most important new technologies of the current century. On demographic advantages, the Baby Boomers and their Medicare and Social Security entitlements will present just a great a demographic challenge for the US as other countries face.At the peak of its global power the United Kingdom was a net creditor, but as it entered the twentieth century, it started losing its economic dominance to Germany and the United States. In contrast, the United States is a large net debtor. But in its case, no plausible challenger to its economic leadership exists, and its share of the global economy will not decline. Focusing exclusively on the NIIP obscures the United States' institutional, technological, and demographic advantages. Such advantages are further bolstered by the underlying complementarities between the U.S. economy and the economies of the developing world--especially those in Asia. The United States continues to reap major gains from what Charles de Gaulle called its "exorbitant privilege," its unique role in providing global liquidity by running chronic external imbalances. The resulting inflow of productivity-enhancing capital has strengthened its underlying economic position. Only one development could upset this optimistic prognosis: an end to the technological dynamism, openness to trade, and flexibility that have powered the U.S. economy. The biggest threat to U.S. hegemony, accordingly, stems not from the sentiments of foreign investors, but from protectionism and isolationism at home.

But these are factors that will play out over many years or decades. More relevant to the crisis at hand is the political antecedent of Ka-Poom Theory, poor distribution of wealth and income. What can we expect as the domestic political reaction to a slowing in "the growth of U.S. consumers' standard of living" that the TD Capital Economics team explains "could very well feel like a recession to many people" under these conditions?

The political response to the coming recession is already cued up on the airwaves by populists like Lou Dobbs and Patrick Buchanan, who prescribe a cure for Globologne* that's worse than the disease. To be sure, the playing field represented by Globologne needs to be leveled. But to the extent that the markets are already pricing in the US political response to the next crisis, the era of "exorbitant privilege" may come to a sudden end in a "Black Swan" event. The IMF recently said that a "disorderly' drop in the dollar is the biggest risk to world financial markets." This will be both the cause and the result of flight capital going the "wrong" way in a US-centric financial crisis, after which not only the playing field may be leveled but the global economy as well.

To the extent that relative economic strength drives investment flows and currency values, might the economy with the least number of credit-worthy borrowers represent the greatest risk to GDP growth in an economy that has become as dependent on real estate for growth as the US has over the past six years? Here TD Capital Economics includes a chart that may be more significant than any other in the report. It suggests that just as US banks are tightening lending standards, reducing zero money down loans and returning to the more standard requirement for 20% down and proof of income to support the other 80% financed, the number of US families that qualifies is steadily declining.

* Globologne: A system of global trade that unequally benefits owners of capital over labor.

Comment