Ka-Poom is a Rhyme not a Repeat of History

In a World of Floating Exchange Rates and Fiat Money, What Goes Down, Must Come Up

by Eric Janszen

September 18, 2006

I've been reading Nassim Taleb's Fooled by Randomness: The Hidden Role of Chance in Life and in the Markets . The book is about the various ways in which we humans insist on seeing patterns and determinism in random events. Taleb is cleverly entertaining as he makes his points. A few chapter headings will give you the idea: "If you're rich, how come you're not so smart?" "Too many millionaires next door." "It is easier to buy and sell than fry an egg." "Loser takes all–the nonlinearities of life." "Gamblers' ticks and pigeons in a box." My favorite, and the one most relevant to our story today, "Randomness, nonsense, and the scientific intellectual."

. The book is about the various ways in which we humans insist on seeing patterns and determinism in random events. Taleb is cleverly entertaining as he makes his points. A few chapter headings will give you the idea: "If you're rich, how come you're not so smart?" "Too many millionaires next door." "It is easier to buy and sell than fry an egg." "Loser takes all–the nonlinearities of life." "Gamblers' ticks and pigeons in a box." My favorite, and the one most relevant to our story today, "Randomness, nonsense, and the scientific intellectual."

I recommend the book, in spite of one major flaw. Taleb reminds me of a chiropractor who is not satisfied that his treatments are highly effective for curing back problems and begins to widen their application to include more refutable claims, such as that conditions ranging from the common cold to depression can be treated by his methods as well. Taleb believes, for example, that the success of most CEOs is due to luck. I can say from personal experience that for a CEO to achieve a positive outcome for investors, far too many things can and will go wrong for much if anything to be left to luck.

A CEO may well go into the job on a rising tide–a head start in a fast growing market, a big pipeline of deals and hot new products that were in the works when the previous CEO left, or a generous swell of money from the Fed that lifts the leaky trawlers in his industry along with the racing yachts, or all three, as several lucky CEOs experienced during the dot com bubble. But the final legacy for any CEO under "normal" market conditions–should we ever see them again, uninfluenced as they have been since 1970's by the ebb and flow of bubble and anti-bubble monetary tides–has more to do with rigorous planning and, if not flawless execution, at least execution that's better than the other guy's. Admittedly, in some markets that's a low bar, but most importantly, the rule for CEOs is that they need to make their luck, and in the same way as politicians and central bankers do: by getting out while the going is good and by not rushing in where angels fear to tread.

If a CEO, politician or central banker hangs around long enough, circumstances either of his own making or not will sooner or later overtake him or her. The Genius becomes The Goat. Greenspan left the Fed Chairman job after 18 years to high fives from everyone from Joe Sixpack flipping houses in Orange County to Gastby II running his hedge fund out of Greenwich, Conn. Now that's one smart geezer. With a storm of credit collapse hitting US shores, Ben Bernanke has stepped into the biggest goat job in central banking history. And that ain't luck. Then again, Greenspan took the job just months before the 1987 stock market crash, so maybe the timing rule for politicians and CEOs doesn't apply to central bankers, they have to prove their mettle as high priests of money, and keep the believers believing through the inevitable Next Crisis.

Taleb can be forgiven for this excess–his general thesis is spot on, that much in this world that is attributed to brains and effort is little more than dumb luck. It should be required reading for all mutual, hedge, private equity, and VC fund managers.

Mindful that the positive ratio of my successes to failures at economic and market predictions to date may owe more to luck than to rigorous planning and execution, I torture my readers with constant floggings of the key hypothesis, Ka-Poom Theory, which is the framework for these forecasts. Taleb, if he were reading this, may be happier to call Ka-Poom a "prophecy." (Or maybe not. I wrote to Taleb and asked, "Which, if any, of these sins applies to me: Epistemic libertarian, Narrative discipline, Narrative fallacy, or Ludic fallacy?" He replied, "I visited the site. No sin applies to you!")

Before the latest flogging begins, a brief definition of terms that are often misused in the seemingly endless debate of post credit bubble "flations"–inflation, deflation and disinflation.

Deflation: Negative rate of inflation, e.g., "CPI inflation averaged -1.3% in 2007."

Disinflation: Declining rate of inflation, e.g., "CPI inflation declined to 2.1% in Q4 2007 from 2.5% in Q3 2007."

Inflation: To an economist, an increase in the general or "all goods" price level resulting from an oversupply of money; to a government statistician, a political football thrown onto the field as producer and consumer price indexes, continuously reformulated and subject to interpretations invented to suit various constituencies over time, such as under-reporting home price inflation via an equivalent rent formula when home prices are rising and rents are falling, in order to hide the fact of a housing bubble that is needed to keep the economy from falling into recession; to the person on the street, rapidly rising prices of non-traded goods and services, especially insurance, education, and health care, resulting from an excess of cheap credit and the inappropriate use of credit to purchase depreciating assets.

The "Ka" in Ka-Poom refers to a period of disinflation while the "Poom" refers to a period of rapid inflation.

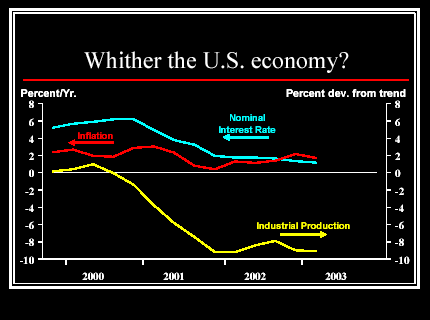

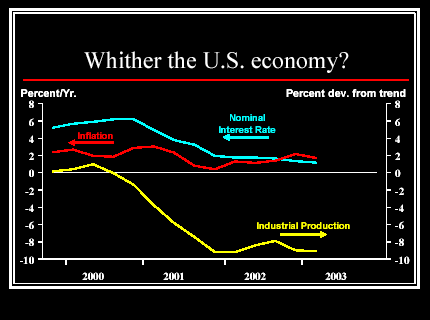

Ka-Poom assumes that the Fed is not kidding when it says it will fight deflation as seriously next time around as the last time it encountered the threat. During the previous "Ka" disinflation, the US economy experienced actual deflation, albeit very brief; CPI averaged -3.3% for the single month of October 2001. You don't see it in Koeing's "Whither the US Economy?" chart below because his chart shows average quarterly inflation, and in the fourth quarter of 2001 CPI inflation was positive–barely. CPI inflation during 2001 averaged a mere 1.6%. Extending the metaphor I used in last week's weekly commentary, "No Deflation! Disinflation followed by lots of inflation" the economic airplane did bounce off the ground very briefly before heading back into the sky. Had the plane not been moving fast enough, because the Fed had not aggressively cut interest rates and fueled the system with enough money, it would have stayed on the ground as happened in Japan in the early 1990s. It took the BoJ and policy makers nearly 15 years to get their economic airplane back in the air.

In November 2002, Fed Governor Ben Bernanke, then gunning for the Fed Chairman goat job, made his famous speech on deflation that earned him the nickname "Helicopter Ben" in market bear circles. The speech was intended to supply a context for future Fed actions–his. At the time he made it, the deflation scare was already behind us. But the specter of deflation, in light of all the new leveraged asset bubbles forming, in everything from real estate to private equity, was certainly going to be on the bond market's collective mind in the future.

The Fed's public talk of deflation in the context of any specific financial markets crisis that threatens to spill over into the so-called "real economy," such as the collapse of the stock market bubble in 2000, is intended to explain to the bond market why the Fed is about to dramatically drop interest rates and open the floodgates. If the Fed did so without first talking about deflation, the bond market is left to wonder whether the Fed has some other intention besides economic rescue, or, conversely, is not on top of the problem. In the context of a market "event," the bond market must believe that inflation is falling and in danger of declining into negative territory, so that bond traders accept higher bond prices and allow long term interest rates to fall in line behind the Fed as it cuts rates, else a deflation may become self-fulfilling.

The Fed is never talking to you or me, nor to players in the puny little stock market that has a capitalization that is a fraction of the bond market's. When the Fed talks, it's talking to bond traders. Next time you hear Ben talk about deflation after a financial markets "event," you can be certain that the money drop is already in progress, and that the Fed has reflation Plans B, C, D, and E in case the Plan A doesn't work.

"You gotta believe!" the Preacher said

In addition to luck, "belief" makes a larger contribution to market outcomes than is generally assumed. There is an excellent piece on deflation by Adam Posen, "What Japanese deflation did and did not do (pdf)," where he argues convincingly how much speech and action by the Fed on inflation targeting and deflation fighting contribute to the non-deflationary outcome. This Fed has been quite vocal on both inflation targeting and deflation fighting.

A reader of my last piece on this topic, skeptical that the Fed can win the next battle with deflation, made the excellent point that debt was not a major factor in the dot com bubble, thus the Fed was fighting mere negative wealth effects. In the case of the collapsing housing and hedge fund bubbles, the Fed will be battling both negative wealth effects and the potential bankruptcy of millions of households that took out suicide loans (options ARMs), liar loans (the banker encouraged the borrower to lie about their income), and deathbed loans (negative amortization loans). These comprise fully 36% of all mortgages in CA, according to a September 11 article by Business Week Nightmare Mortgages. The Fed will also be dealing with the potential insolvency of the banks that made these loans. The reader also pointed out that the dot com bubble collapsed rapidly while the housing bubble will collapse slowly.

I agree wholeheartedly on both points. Housing Bubbles Unlike Stock Bubbles made the point in Jan. 2004 that housing bubbles end by seizing up and decline slowly over five to seven years, or longer. As for household bankruptcy and bank insolvency, the difference between healthy and unhealthy deflation is that the latter is associated with a dysfunctional banking system and the former is not. Whether the deflation egg makes the banking system dysfunction chicken or the other way around is endlessly debated by economics historians. As far as the Fed's concerned, rather than try to get the economy out of the egg-chicken deflation cycle, best to keep one from starting in the first place. As a matter of policy, the Fed clearly believes that deflation cannot be healthy and can lead to banking system dysfunction, which can lead to further deflation, and so on, so don't let the process start in the first place.

To give you an idea how serious the Fed is about staying on top of deflation, I'll point to two papers issued since 2002. The first predates Ben's November 2002 speech by a few months. It makes essentially the same point as Ben's speech: when staring down the hole of deflation the Fed needs to get creative and aggressive.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

International Finance Discussion Papers – Number 729 – June 2002

Preventing Deflation: Lessons from Japan’s Experience in the 1990s (pdf)

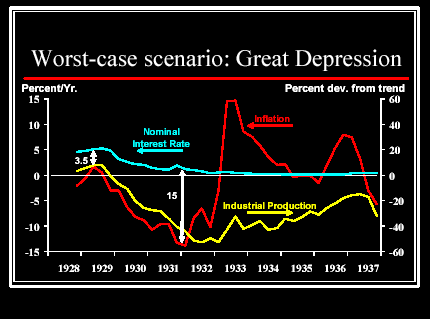

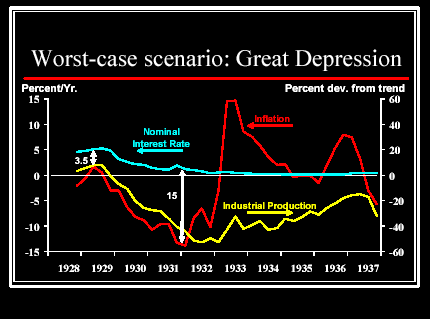

Don't let this happen

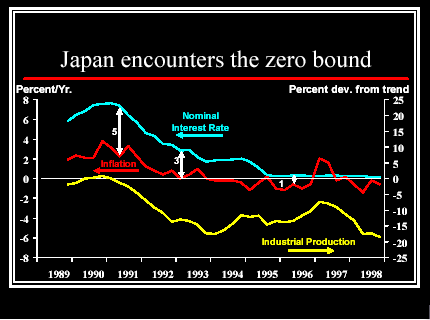

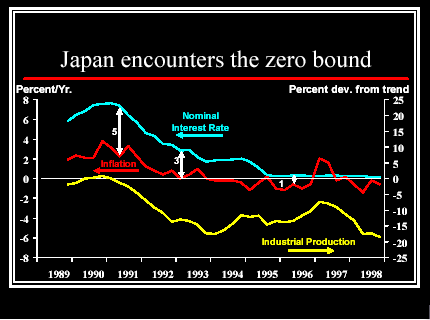

Or this

Do use all means to keep inflation above the zero bound, like this

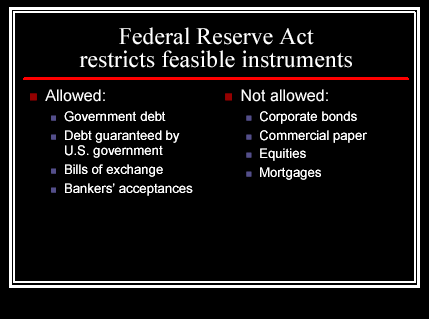

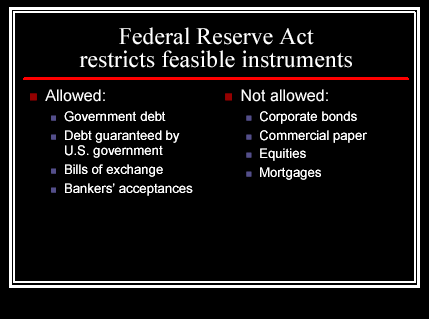

Drop tons of money if needed

If necessary to drop tons of money, change the rules to reclassify

previously restricted instruments as unrestricted so that the Fed can

print money and buy them

In a World of Floating Exchange Rates and Fiat Money, What Goes Down, Must Come Up

by Eric Janszen

September 18, 2006

I've been reading Nassim Taleb's Fooled by Randomness: The Hidden Role of Chance in Life and in the Markets

I recommend the book, in spite of one major flaw. Taleb reminds me of a chiropractor who is not satisfied that his treatments are highly effective for curing back problems and begins to widen their application to include more refutable claims, such as that conditions ranging from the common cold to depression can be treated by his methods as well. Taleb believes, for example, that the success of most CEOs is due to luck. I can say from personal experience that for a CEO to achieve a positive outcome for investors, far too many things can and will go wrong for much if anything to be left to luck.

A CEO may well go into the job on a rising tide–a head start in a fast growing market, a big pipeline of deals and hot new products that were in the works when the previous CEO left, or a generous swell of money from the Fed that lifts the leaky trawlers in his industry along with the racing yachts, or all three, as several lucky CEOs experienced during the dot com bubble. But the final legacy for any CEO under "normal" market conditions–should we ever see them again, uninfluenced as they have been since 1970's by the ebb and flow of bubble and anti-bubble monetary tides–has more to do with rigorous planning and, if not flawless execution, at least execution that's better than the other guy's. Admittedly, in some markets that's a low bar, but most importantly, the rule for CEOs is that they need to make their luck, and in the same way as politicians and central bankers do: by getting out while the going is good and by not rushing in where angels fear to tread.

If a CEO, politician or central banker hangs around long enough, circumstances either of his own making or not will sooner or later overtake him or her. The Genius becomes The Goat. Greenspan left the Fed Chairman job after 18 years to high fives from everyone from Joe Sixpack flipping houses in Orange County to Gastby II running his hedge fund out of Greenwich, Conn. Now that's one smart geezer. With a storm of credit collapse hitting US shores, Ben Bernanke has stepped into the biggest goat job in central banking history. And that ain't luck. Then again, Greenspan took the job just months before the 1987 stock market crash, so maybe the timing rule for politicians and CEOs doesn't apply to central bankers, they have to prove their mettle as high priests of money, and keep the believers believing through the inevitable Next Crisis.

Taleb can be forgiven for this excess–his general thesis is spot on, that much in this world that is attributed to brains and effort is little more than dumb luck. It should be required reading for all mutual, hedge, private equity, and VC fund managers.

Mindful that the positive ratio of my successes to failures at economic and market predictions to date may owe more to luck than to rigorous planning and execution, I torture my readers with constant floggings of the key hypothesis, Ka-Poom Theory, which is the framework for these forecasts. Taleb, if he were reading this, may be happier to call Ka-Poom a "prophecy." (Or maybe not. I wrote to Taleb and asked, "Which, if any, of these sins applies to me: Epistemic libertarian, Narrative discipline, Narrative fallacy, or Ludic fallacy?" He replied, "I visited the site. No sin applies to you!")

Before the latest flogging begins, a brief definition of terms that are often misused in the seemingly endless debate of post credit bubble "flations"–inflation, deflation and disinflation.

Deflation: Negative rate of inflation, e.g., "CPI inflation averaged -1.3% in 2007."

Disinflation: Declining rate of inflation, e.g., "CPI inflation declined to 2.1% in Q4 2007 from 2.5% in Q3 2007."

Inflation: To an economist, an increase in the general or "all goods" price level resulting from an oversupply of money; to a government statistician, a political football thrown onto the field as producer and consumer price indexes, continuously reformulated and subject to interpretations invented to suit various constituencies over time, such as under-reporting home price inflation via an equivalent rent formula when home prices are rising and rents are falling, in order to hide the fact of a housing bubble that is needed to keep the economy from falling into recession; to the person on the street, rapidly rising prices of non-traded goods and services, especially insurance, education, and health care, resulting from an excess of cheap credit and the inappropriate use of credit to purchase depreciating assets.

The "Ka" in Ka-Poom refers to a period of disinflation while the "Poom" refers to a period of rapid inflation.

Ka-Poom assumes that the Fed is not kidding when it says it will fight deflation as seriously next time around as the last time it encountered the threat. During the previous "Ka" disinflation, the US economy experienced actual deflation, albeit very brief; CPI averaged -3.3% for the single month of October 2001. You don't see it in Koeing's "Whither the US Economy?" chart below because his chart shows average quarterly inflation, and in the fourth quarter of 2001 CPI inflation was positive–barely. CPI inflation during 2001 averaged a mere 1.6%. Extending the metaphor I used in last week's weekly commentary, "No Deflation! Disinflation followed by lots of inflation" the economic airplane did bounce off the ground very briefly before heading back into the sky. Had the plane not been moving fast enough, because the Fed had not aggressively cut interest rates and fueled the system with enough money, it would have stayed on the ground as happened in Japan in the early 1990s. It took the BoJ and policy makers nearly 15 years to get their economic airplane back in the air.

In November 2002, Fed Governor Ben Bernanke, then gunning for the Fed Chairman goat job, made his famous speech on deflation that earned him the nickname "Helicopter Ben" in market bear circles. The speech was intended to supply a context for future Fed actions–his. At the time he made it, the deflation scare was already behind us. But the specter of deflation, in light of all the new leveraged asset bubbles forming, in everything from real estate to private equity, was certainly going to be on the bond market's collective mind in the future.

The Fed's public talk of deflation in the context of any specific financial markets crisis that threatens to spill over into the so-called "real economy," such as the collapse of the stock market bubble in 2000, is intended to explain to the bond market why the Fed is about to dramatically drop interest rates and open the floodgates. If the Fed did so without first talking about deflation, the bond market is left to wonder whether the Fed has some other intention besides economic rescue, or, conversely, is not on top of the problem. In the context of a market "event," the bond market must believe that inflation is falling and in danger of declining into negative territory, so that bond traders accept higher bond prices and allow long term interest rates to fall in line behind the Fed as it cuts rates, else a deflation may become self-fulfilling.

The Fed is never talking to you or me, nor to players in the puny little stock market that has a capitalization that is a fraction of the bond market's. When the Fed talks, it's talking to bond traders. Next time you hear Ben talk about deflation after a financial markets "event," you can be certain that the money drop is already in progress, and that the Fed has reflation Plans B, C, D, and E in case the Plan A doesn't work.

"You gotta believe!" the Preacher said

In addition to luck, "belief" makes a larger contribution to market outcomes than is generally assumed. There is an excellent piece on deflation by Adam Posen, "What Japanese deflation did and did not do (pdf)," where he argues convincingly how much speech and action by the Fed on inflation targeting and deflation fighting contribute to the non-deflationary outcome. This Fed has been quite vocal on both inflation targeting and deflation fighting.

A reader of my last piece on this topic, skeptical that the Fed can win the next battle with deflation, made the excellent point that debt was not a major factor in the dot com bubble, thus the Fed was fighting mere negative wealth effects. In the case of the collapsing housing and hedge fund bubbles, the Fed will be battling both negative wealth effects and the potential bankruptcy of millions of households that took out suicide loans (options ARMs), liar loans (the banker encouraged the borrower to lie about their income), and deathbed loans (negative amortization loans). These comprise fully 36% of all mortgages in CA, according to a September 11 article by Business Week Nightmare Mortgages. The Fed will also be dealing with the potential insolvency of the banks that made these loans. The reader also pointed out that the dot com bubble collapsed rapidly while the housing bubble will collapse slowly.

I agree wholeheartedly on both points. Housing Bubbles Unlike Stock Bubbles made the point in Jan. 2004 that housing bubbles end by seizing up and decline slowly over five to seven years, or longer. As for household bankruptcy and bank insolvency, the difference between healthy and unhealthy deflation is that the latter is associated with a dysfunctional banking system and the former is not. Whether the deflation egg makes the banking system dysfunction chicken or the other way around is endlessly debated by economics historians. As far as the Fed's concerned, rather than try to get the economy out of the egg-chicken deflation cycle, best to keep one from starting in the first place. As a matter of policy, the Fed clearly believes that deflation cannot be healthy and can lead to banking system dysfunction, which can lead to further deflation, and so on, so don't let the process start in the first place.

To give you an idea how serious the Fed is about staying on top of deflation, I'll point to two papers issued since 2002. The first predates Ben's November 2002 speech by a few months. It makes essentially the same point as Ben's speech: when staring down the hole of deflation the Fed needs to get creative and aggressive.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

International Finance Discussion Papers – Number 729 – June 2002

Preventing Deflation: Lessons from Japan’s Experience in the 1990s (pdf)

"Once inflation turned negative and short-term interest rates approached the zero-lower-bound, it became much more difficult for monetary policy to reactivate the economy. We found little compelling evidence that in the lead up to deflation in the first half of the 1990s, the ability of either monetary or fiscal policy to help support the economy fell off significantly. Based on all these considerations, we draw the general lesson from Japan’s experience that when inflation and interest rates have fallen close to zero, and the risk of deflation is high, stimulus–both monetary and fiscal–should go beyond the levels conventionally implied by baseline forecasts of future inflation and economic activity.

The second comes from Evan F. Koenig, Vice President (pdf), Senior Economist, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, May 2003, where Bernanke's helicopter speech is colorfully embellished, complete with a picture of an actual helicopter.

Don't let this happen

Or this

Do use all means to keep inflation above the zero bound, like this

Drop tons of money if needed

If necessary to drop tons of money, change the rules to reclassify

previously restricted instruments as unrestricted so that the Fed can

print money and buy them

Given the level of commitment by this Fed to change whatever existing rules need to be changed to keep inflation above zero in the face of deflation, that leaves us with the question: Will it work?

Ka-Poom Theory is a hypothesis that not only will stimulus "both monetary and fiscal–beyond the levels conventionally implied by baseline forecasts of future inflation and economic activity" succeed in preventing deflation, these unconventional means will work too well. The main reason is that during the deflationary depresssion in the US in the 1930s and the deflationary recession in Japan in the 1990s, both countries were net creditors whereas today the US is a net debtor. The Fed now needs to be mindful that there are trillions of dollars held overseas by creditors who will want to see the US take some of the same medicine the IMF demands be taken by debtor countries that are using freshly money borrowed from other countries to restructure after blowing the last money they'd borrowed: fiscal discipline in the form of higher taxes and spending cuts. Indeed the Fed proposes the opposite policy strategy for the next round of post-bubble deflation fighting–even further cuts in taxes, even more government spending and all manner of new kinds of printing to pay for it all. If the Fed intends to "go it alone," then these creditors will worry that the US intends to pay them back on the cheap. If you were in their shoes, what would you do?

In other words, I don't think these laxatives can cure the next post-bubble economic constipation without causing severe monetary diarrhea.

"History does not repeat itself, but it rhymes." - Mark Twain

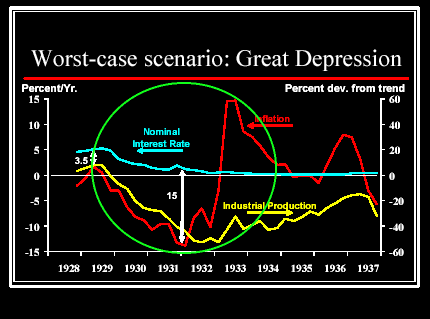

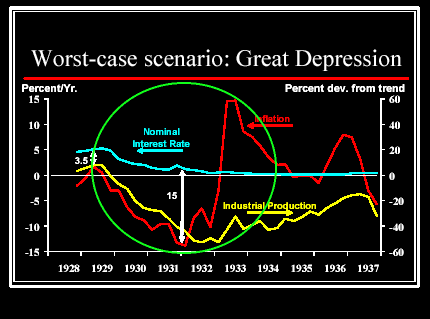

Sharp eyed iTulip forum member Jim Nickerson noticed something in the graph titled "Worse-case scenario: Great Depression" above, a distinctly "Ka-Poom" like event that happened between 1928 and 1933. Jim is the first person to ever note the source of the original source of my Ka-Poom idea.

Ka-Poom Theory is a hypothesis that not only will stimulus "both monetary and fiscal–beyond the levels conventionally implied by baseline forecasts of future inflation and economic activity" succeed in preventing deflation, these unconventional means will work too well. The main reason is that during the deflationary depresssion in the US in the 1930s and the deflationary recession in Japan in the 1990s, both countries were net creditors whereas today the US is a net debtor. The Fed now needs to be mindful that there are trillions of dollars held overseas by creditors who will want to see the US take some of the same medicine the IMF demands be taken by debtor countries that are using freshly money borrowed from other countries to restructure after blowing the last money they'd borrowed: fiscal discipline in the form of higher taxes and spending cuts. Indeed the Fed proposes the opposite policy strategy for the next round of post-bubble deflation fighting–even further cuts in taxes, even more government spending and all manner of new kinds of printing to pay for it all. If the Fed intends to "go it alone," then these creditors will worry that the US intends to pay them back on the cheap. If you were in their shoes, what would you do?

In other words, I don't think these laxatives can cure the next post-bubble economic constipation without causing severe monetary diarrhea.

"History does not repeat itself, but it rhymes." - Mark Twain

Sharp eyed iTulip forum member Jim Nickerson noticed something in the graph titled "Worse-case scenario: Great Depression" above, a distinctly "Ka-Poom" like event that happened between 1928 and 1933. Jim is the first person to ever note the source of the original source of my Ka-Poom idea.

Ka-Poom happened before and it will likely happen again,

and for similar reasons, but in not quite the same way

and for similar reasons, but in not quite the same way

The differences between our circumstances today and the 1930s are many, which is why Ka-Poom is a rhyme not a repeat of history.

First, what are the similarities? Ka-Poom Theory says that three primary antecedents for a massive deflationary impulse are the same now as in the 1930's followed by a major inflation.

First, historically high total credit market debt-to-GDP levels.

Source: Gabelli Mathers Fund

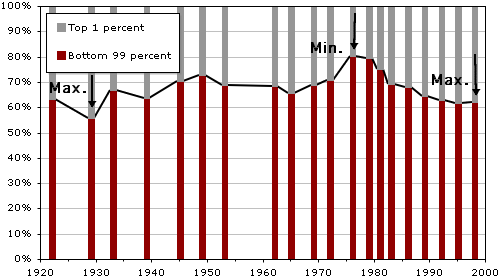

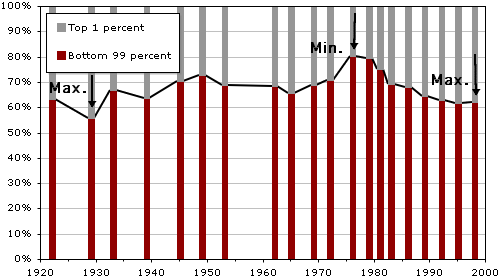

Second, extremes of income and wealth distribution.

Peaks of income inequality

Peaks of wealth inequality

Source: Northern Trust

First, what are the similarities? Ka-Poom Theory says that three primary antecedents for a massive deflationary impulse are the same now as in the 1930's followed by a major inflation.

First, historically high total credit market debt-to-GDP levels.

Source: Gabelli Mathers Fund

Second, extremes of income and wealth distribution.

Peaks of income inequality

Peaks of wealth inequality

There are three important differences between the 1930s post credit bubble period and today's.

First, going into the 1930s crisis, the US was a net creditor to the world. When borrowers, especially the UK, defaulted, this made matters much worse for the US from a reflation standpoint. Creating inflation is generally more difficult for creditor nations because the nation's currency tends to appreciate during periods of credit contraction, as occurred in the US in the 1930s and in Japan in the 1990s.

Second, the US dollar operated on a gold standard. The spike of inflation that can be seen in 1932 was accomplished as follows. On April 5, 1933, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt issued Presidential Executive Order 6102 calling in gold owned for the purpose of "hoarding." However, long before that order was in place, most wealthy holders of gold had already turned in their gold to the government voluntarily. Private citizens were paid for the gold in dollars at a going rate of $20.67 per ounce. The Treasury then reset the price of gold to $35 per ounce, thus devaluing the dollar and boosting the gold-backed dollar money supply, resulting in the near instantaneous 25% inflation spike that you see in the chart.

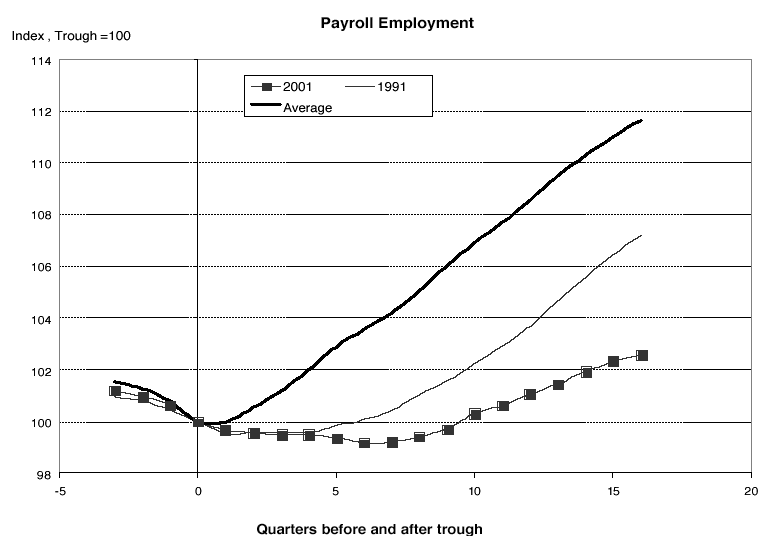

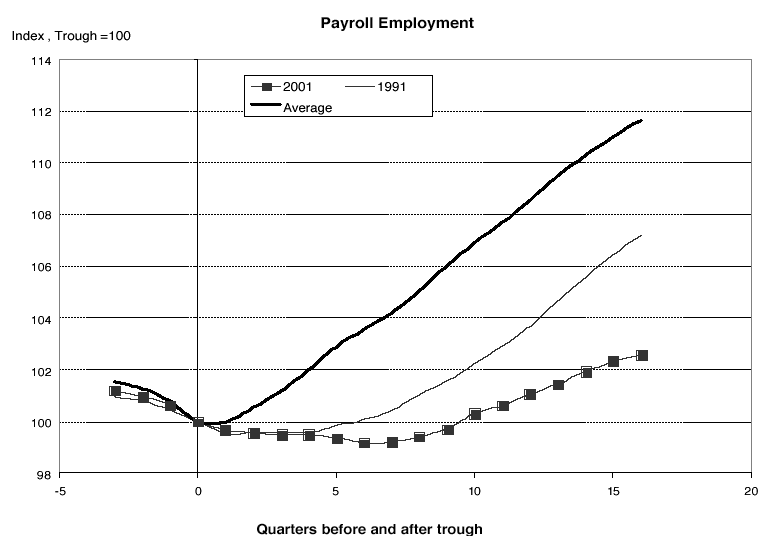

Third, the US is in its sixth year of economic "recovery" since the post 2000 stock market crash, yet unlike the 1920s boom period, this recovery has created very few jobs. As a result, unemployment and underemployment are both high, and far higher than is reported.

First, going into the 1930s crisis, the US was a net creditor to the world. When borrowers, especially the UK, defaulted, this made matters much worse for the US from a reflation standpoint. Creating inflation is generally more difficult for creditor nations because the nation's currency tends to appreciate during periods of credit contraction, as occurred in the US in the 1930s and in Japan in the 1990s.

Second, the US dollar operated on a gold standard. The spike of inflation that can be seen in 1932 was accomplished as follows. On April 5, 1933, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt issued Presidential Executive Order 6102 calling in gold owned for the purpose of "hoarding." However, long before that order was in place, most wealthy holders of gold had already turned in their gold to the government voluntarily. Private citizens were paid for the gold in dollars at a going rate of $20.67 per ounce. The Treasury then reset the price of gold to $35 per ounce, thus devaluing the dollar and boosting the gold-backed dollar money supply, resulting in the near instantaneous 25% inflation spike that you see in the chart.

Third, the US is in its sixth year of economic "recovery" since the post 2000 stock market crash, yet unlike the 1920s boom period, this recovery has created very few jobs. As a result, unemployment and underemployment are both high, and far higher than is reported.

Source: Northern Trust

The implications of the private and public debt overhang are obvious, and why the Fed and the IMF are constantly fretting about deflation. The US now requires $4.50 of new debt creation for every dollar of GDP versus $2 in 1975. It is hard to accept the argument that the US economy can grow its way out of a debt that it has amassed over 25 years as the US economy requires increasingly more debt as a percentage of GDP just to maintain current growth rates.

$2 total debt per $1 GDP in 1977

$4.5 total debt per $1 GDP 2005

The implications of poor distribution of wealth are less obvious. What happened in the 1930s will likely happen again. In a recession, a small minority of the nation's population that garners most of the income and holds most of the nation's wealth and assets cannot generate enough demand to re-employ the majority. As the credit bubble winds down, the US government will find itself with a politically similar challenge as in the 1930s: How to get the wealth spread around and the economy going again? But inflation is much easier to create today without the constraints of the gold standard. Stubborn adherence to the gold standard was in fact blamed for much of the pain, and The Great Depression could have been avoided if only the Fed had been free to print money and buy stuff, just as they are today.

Conclusion

The economic, monetary, financial market, and political antecedents are all in place for a Ka-Poom event. As I mentioned last week, the disinflationary part of the event appears to have started, but no one can say how far it will go before policy makers reverse course, making the transition difficult to time and trade.

Ka-Poom Theory provides a framework for a long term forecast. In the short term, Taleb's points about randomness apply. We'll keep an eye on the markets and economy and discuss Ka-Poom events here as they unfold.

If you'd like to know what to do about Ka-Poom, I recommend you buy America's Bubble Economy: Profit When It Pops for specific advice.

As for a short term forecast, I defer to Doris Day, whose classic song about forecasting is lip synched (sort of) below.

$2 total debt per $1 GDP in 1977

$4.5 total debt per $1 GDP 2005

The implications of poor distribution of wealth are less obvious. What happened in the 1930s will likely happen again. In a recession, a small minority of the nation's population that garners most of the income and holds most of the nation's wealth and assets cannot generate enough demand to re-employ the majority. As the credit bubble winds down, the US government will find itself with a politically similar challenge as in the 1930s: How to get the wealth spread around and the economy going again? But inflation is much easier to create today without the constraints of the gold standard. Stubborn adherence to the gold standard was in fact blamed for much of the pain, and The Great Depression could have been avoided if only the Fed had been free to print money and buy stuff, just as they are today.

Conclusion

The economic, monetary, financial market, and political antecedents are all in place for a Ka-Poom event. As I mentioned last week, the disinflationary part of the event appears to have started, but no one can say how far it will go before policy makers reverse course, making the transition difficult to time and trade.

Ka-Poom Theory provides a framework for a long term forecast. In the short term, Taleb's points about randomness apply. We'll keep an eye on the markets and economy and discuss Ka-Poom events here as they unfold.

If you'd like to know what to do about Ka-Poom, I recommend you buy America's Bubble Economy: Profit When It Pops for specific advice.

As for a short term forecast, I defer to Doris Day, whose classic song about forecasting is lip synched (sort of) below.

crazylittleblonde

Qué Será, Será

Qué Será, Será

Join our FREE Email Mailing List

Copyright © iTulip, Inc. 1998 - 2006 All Rights Reserved

All information provided "as is" for informational purposes only, not intended for trading purposes or advice. Nothing appearing on this website should be considered a recommendation to buy or to sell any security or related financial instrument. iTulip, Inc. is not liable for any informational errors, incompleteness, or delays, or for any actions taken in reliance on information contained herein. Full Disclaimer

Copyright © iTulip, Inc. 1998 - 2006 All Rights Reserved

All information provided "as is" for informational purposes only, not intended for trading purposes or advice. Nothing appearing on this website should be considered a recommendation to buy or to sell any security or related financial instrument. iTulip, Inc. is not liable for any informational errors, incompleteness, or delays, or for any actions taken in reliance on information contained herein. Full Disclaimer

Comment